Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Employees’ Sense of Entitlement Toward Their Supervisors and its Association with Burnout and Job Satisfaction: Assessing A Multidimensional Construct Volume 5 - Issue 4

Rinat Cohen1, Sivanie Shiran2 and Rami Tolmacz1*

- 1Department of Psychology, The Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Israel Hauniversity 8, Israel

- 2Department of Business management, The Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Israel

Received:August 19, 2021 Published:August 30, 2021

Corresponding author:Rami Tolmacz, Department of Psychology, The Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Israel , Hauniversity 8, Herzliya, Israel

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2021.05.000220

Abstract

There has been increased interest on the part of both organizations and the academy in the entitlement attitudes of employees. The vast majority of studies on employee entitlement have construed it as a unidimensional dispositional trait and have generally revealed strong correlations between sense of entitlement and negative workplace behaviors, suggesting significant implications for organizational outcomes. The goal of the current study was to develop and validate a self-report measure that views employees’ sense of relational entitlement toward their supervisors (SRE-es) as multifactorial. Findings indicated initial evidence of the validity of the SRE-es three-factor structure, reflecting employees’ adaptive (assertive) as well as pathological (restricted or exaggerated) attitudes regarding the assertion of their needs and rights toward their supervisors. Findings also indicated that an assertive sense of entitlement was linked with high job satisfaction and low burnout. Conversely, an exaggerated sense of entitlement was associated with high burnout and low job satisfaction. Restricted sense of entitlement revealed a mixed trend, being linked with both burnout and job satisfaction. The potential uses of the SRE-es scale are discussed.

Keywords: Employee Entitlement; Psychological Entitlement; Work Satisfaction; Work Burnout

Introduction

During the last decade, interest in employees’ sense of entitlement, broadly defined as “an excessive self-regard and a belief in the automatic right to privileged treatment at work” [1], has increased greatly both in organizations and in the academic world [2-8]. Previous studies have revealed that employees’ sense of entitlement has significant implications for their functioning in the workplace, and thereby for overall organizational performance and outcomes. For example, it was found that entitled employees reported having more conflicts with their supervisors, lower job satisfaction [9,10], thoughts regarding quitting their jobs [11], abusiveness toward coworkers [11], unethical pro-organizational behavior [12], and increased levels of aggressive behaviors [13- 15] suggested that feelings of being entitled are a result of these individuals’ inclination toward feeling that they are being mistreated by others. Although most studies have revealed associations between employees’ sense of entitlement and negative outcomes [16-18], a number of studies have indicated that employees’ sense of entitlement might also be associated with positive outcomes [19- 24]. These contradicting outcomes led several researchers to point to the need for further research in order to better understand the nature of employees’ sense of entitlement and its implications for the workplace [2,4,12]. In the current study we aimed to contribute to this challenge by applying a multidimensional perspective to employees’ sense of entitlement [25-28], rather than applying the unidimensional dispositional trait that has been construed by the vast majority of studies on employee entitlement [29,30].

Conceptualizing the sense of entitlement in intimate relationships in terms of attachment theory, [15] highlighted its universal and not necessarily pathological nature, by conceptualizing it in terms of attachment theory, and suggested that it is something that influences us across the lifespan. Furthermore, in accordance with this perspective, entitlement can be adaptive when it is assertive or less adaptive when it is exaggerated or restricted. Based on this approach, psychological entitlement was organized around three main factors: assertive (which reflects an adaptive sense of psychological entitlement) and exaggerated or restricted (reflecting two maladaptive senses of psychological entitlement). An assertive sense of entitlement allows individuals.

to form realistic expectations of others. An exaggerated sense of entitlement is defined as an excessive self-regard of one’s abilities, leading one to have the unrealistic expectation that others should fulfill one’s every need and wish. A restricted sense of entitlement leads people to ignore their genuine needs and wishes and avoid expressing them.

Given this broader definition of sense of entitlement, the purpose of the current study was to investigate whether this approach might provide a better understanding of individual differences in employees’ sense of entitlement toward their supervisors and its relation to positive and negative organizational outcomes. Our aim was to adapt the “sense of relational entitlement” scale [31], which measures entitlement in adult romantic relationships, to a new selfreport scale tapping adaptive and maladaptive manifestations of the sense of relational entitlement among employees toward their supervisors (SRE-es). We then investigated the relations between these multidimensional constructs of entitlement and positive and negative organizational outcomes.

Expanding the investigation of the entitlement construct is crucial both for the organizational field and for the academic investigation of psychological entitlement in the workplace. By conducting such an investigation, we answer the multiple calls by contemporary authors to expand our understanding of employees’ entitlement perceptions and thereby contribute to the growing body of research on this phenomenon [32-36].

Literature Review

Conceptualizations of sense of entitlement

Over the past several decades, entitlement has largely been regarded as a pathological personality trait. Specifically, an exaggerated sense of entitlement has been considered to be a component of psychopathy [37] and an aspect of clinical and subclinical narcissism [38]. However, many researchers have argued that this approach overemphasizes maladaptive forms of entitlement [24,28,32]. As a result, efforts have been made to reconceptualize entitlement as a normative psychological trait that typifies the general population. This approach construes entitlement as a universal phenomenon, encompassing both the pathological and the healthy assertion of needs and rights [39-42]. In addition to this shift in conceptualization, recent research has indicated that psychological entitlement may also be construed as domainspecific; that is, it may be dependent on the specific situational context or relationship in which it is experienced [11,18,19]. For example, one may have a different sense of entitlement in academic contexts and then in romantic relationships [22]. Based on this perspective and developed and validated the SRE scale, which measures an individual’s sense of entitlement in adult romantic relationships.

A series of factor analyses revealed that the SRE was organized around three main factors – assertive, exaggerated, and restricteddescribed and defined above. Previous studies have documented that higher scores on the exaggerated and restricted factors are related to greater emotional difficulties and attachment insecurities, less adaptive personality dispositions, and a decreased sense of well-being, positive mood, and life satisfaction [43-47]. In contrast, higher scores on the assertive factor have been related to more positive aspects of personality dispositions, such as higher self-esteem and self-efficacy, higher life satisfaction, and lower levels of emotional problems [48-51]. This new line of research suggests that important psychological outcomes might be affected by the quality of one’s sense of entitlement and, in particular, the extent to which this sense of entitlement is balanced (assertive) or imbalanced (exaggerated or restricted). However, in all of these studies entitlement has been investigated only in the particular context of intimate relationships (i.e., romantic relationships or adolescent-parent relationships). In the current study we wished to examine whether this differentiation between a balanced and imbalanced sense of entitlement might also be applied to the context of the workplace and organizations, thus contributing to a better understanding of the mixed research findings documented in the literature.

Psychological sense of entitlement in the workplace

Research on people’s excessive sense of psychological entitlement has revealed significant links between this form of entitlement and negative workplace behaviors, yielding costly outcomes for individuals, teams, and organizations, and significant implications for human resources management. For example, studies have indicated that employees who feel highly entitled are more likely to demonstrate increased levels of aggressive behavior [35] and to create in their wake stressed colleagues [45]. Specifically, studies have demonstrated that those who feel highly entitled experience greater conflict with supervisors [11] and may behave more aggressively toward co-workers [24,22,31]. These authors have suggested that highly entitled employees report higher job frustration which, in turn, is associated with insulting co-workers, behaving rudely, and undermining co-workers’ positions with supervisors while simultaneously promoting themselves [15,17,25]. Studies have also shown that employees who feel highly entitled are also more likely to experience lower job satisfaction [20,7,8,2] and higher levels of burnout and stress [10]. Several explanations for these findings have been offered. For example, highly entitled employees may use biased attributions and diminished cognitive elaboration to dismiss negative feedback and performance failures, seeing these failures as the fault of others rather than of themselves [12]. And indicated that entitled employees report primarily on undesirable workplace outcomes, such as job frustration [34], which in turn can lead to coworker abuse and undesirable office politics.

More recently, however, some research evidence has indicated that entitlement may also be linked with positive behaviors at work. He found that highly entitled employees reported greater organizational citizenship behavior. In addition, Langerud & Jordan found that entitled employees voluntarily exhibited more altruistic and collegial behaviors at work and demonstrated high organizational citizenship behavior. These researchers suggested that highly entitled workers feel central to the organization, and by performing altruistic behavior, demonstrate their central position. Similarly [18] showed that highly entitled employees who demonstrate high levels of organizational identification exhibit higher pro-active organizational behavior in comparison to employees with a lower sense of psychological entitlement. This finding was attributed to the idea that highly entitled employees may voluntarily perform altruistic behavior to help others as a way of demonstrating their importance to, and centrality in, their organizations. Previous research also indicated that highly entitled employees may have an optimistic view of the world and themselves, and hold an expectation that life events will go their way [25]. Taken together, these studies, linking sense of entitlement at work with important psychological variables and major behavioral outcomes, point to the need to further examine the implications of sense of entitlement for the workplace and for organizations.

The Current Research

The goal of the current research was to assess whether employees’ sense of entitlement could be conceptualized as incorporating the three relational dimensions that were first outlined [36]- assertive, exaggerated, and restricted – and to validate the adaptation of the original SRE scale to the employeesupervisor context. We defined “employees’ sense of relational entitlement toward their supervisor” (SRE-es) as the manifestation of employees’ expectations that their expectations would be fulfilled, coupled with their affective and cognitive responses to their supervisors’ failures to meet their expectations. We also examined the role of SRE-es in predicting employees’ job satisfaction and burnout. Finally, we verified that the SRE-es constructs could explain the variance over and above the one dimension of the general psychological entitlement scale, thereby rendering these constructs unique. Specifically, we hypothesized that employees with an assertive/adaptive sense of entitlement would report higher levels of job satisfaction and lower levels of burnout. By contrast, we assumed that employees with an imbalanced sense of psychological entitlement (restricted or exaggerated) would report higher levels of burnout and lower job satisfaction.

Method

Sample and procedure

In the current study, 337 employees responded to an online survey pertaining to psychological entitlement as well as to job satisfaction and burnout. Participants were invited to participate via social networking sites. Research assistants posted the invitation to the study for two months. Respondents were informed that participation was voluntary, without remuneration, and that the answers would be analyzed anonymously. The research was approved by the institution’s ethics committee. Approximately 57% of the sample comprised female participants, 49.5% had a college/ university education, and 71.6% were single. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 69 years old, with an average age of 27.56 (SD = 8.07). The total sample of participants (N = 337) was randomly split into two samples, Sample 1 (N = 170) and Sample 2 (N = 167), for performing exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in the scale validation process. Demographic information for Samples 1 and 2 were as follows.

Sample 1 (N = 170)

Approximately 59% of the sample comprised female participants, 72.4% had a college/university education, and 50.4% were single. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 69 years old, with an average age of 31.58 (SD = 9.57).

Sample 2 (N = 167)

Approximately 55% of the sample comprised female participants, 31% had a college/university education, and 88.6% were single. Participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 47 years old, with an average age of 23.84 (SD = 5.71).

Measures

Employees’ sense of entitlement toward their supervisors

Employees’ sense of relational entitlement toward their supervisors was measured via a modified version of the SRE scale [19,5,4]. The original SRE scale assessed the extent to which participants’ expectations of their partners would be fulfilled, as well as their affective and cognitive responses to their partners’ failures to meet their expectations. As such, we modified the 21- item scale to assess participants’ entitlement-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors toward their supervisors. Participants were asked to read each item and to rate the extent to which each item described their attitudes, feelings, beliefs, and reactions toward their supervisors. Ratings were scored on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Items were derived from the original theoretical conceptualization, intended to capture the three patterns of entitlement: exaggerated (“When I feel that I have been hurt by my supervisor, I am filled with deep pain”; “I often feel I deserve more than I get from my supervisor”), restricted (“Sometimes I feel that my supervisor deserves an employee who’s better than I am”; “When my supervisor compliments me on my work, most of the time I do not think I deserve it”), and assertive (“I feel appreciated by my supervisor”; “I maintain good working relations with my supervisor”).

Employee job satisfaction

Employees’ job satisfaction was measured via a scale developed. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with various statements, using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Sample items included, “I feel interested and challenged at work” and “I feel that my professional skills and abilities are reflected in my work.” This 11-item scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .85. A higher score on this variable refers to higher levels of job satisfaction.

Employee burnout

Employee burnout was measured via the short version of the burnout measure (BMS; Burnout Measure, Short Version). The burnout measure was first developed [30], and a shorter version of the instrument was later adapted [14]. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with statements on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Sample items included, “I feel disappointed with people in my workplace” and “I feel hopelessness in my workplace.” This 10-item scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .88. A higher score indicates higher levels of burnout.

Psychological entitlement scale

Employees’ general sense of entitlement was measured via a modified version of the psychological entitlement scale (PES) developed [28]. This scale contains nine items that assess entitlement-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Participants were asked to read each item and to rate the extent to which each of them described their attitudes, feelings, beliefs, and reactions toward their supervisors. Ratings were scored on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) (“I honestly feel that I deserve more than others do”; “I demand the best, because I’m worth it”). This 9-item scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .86. A higher score indicates higher levels of psychological entitlement.

Analyses and Results

The content and factorial validity of the SRE-es scale was tested through EFA. In order to confirm the factor structure of the scale obtained in EFA, we also conducted CFA with data collected from an independent sample. The advantage of using EFA followed by CFA is that EFA can easily identify the items that have cross-loadings or mis-loadings in other factors, while CFA can further crossvalidate the factorial structure as well as test the model-data fit [11-18]. These analyses (EFA and CFA) were conducted for Sample 1 and Sample 2. We also examined the role of SRE-es in predicting employees’ job satisfaction and burnout. Finally, we verified that the SRE-es constructs could explain the variance over and above the one dimension of the psychological entitlement at work scale, thereby rendering these constructs unique.

EFA with Sample 1 (N = 170)

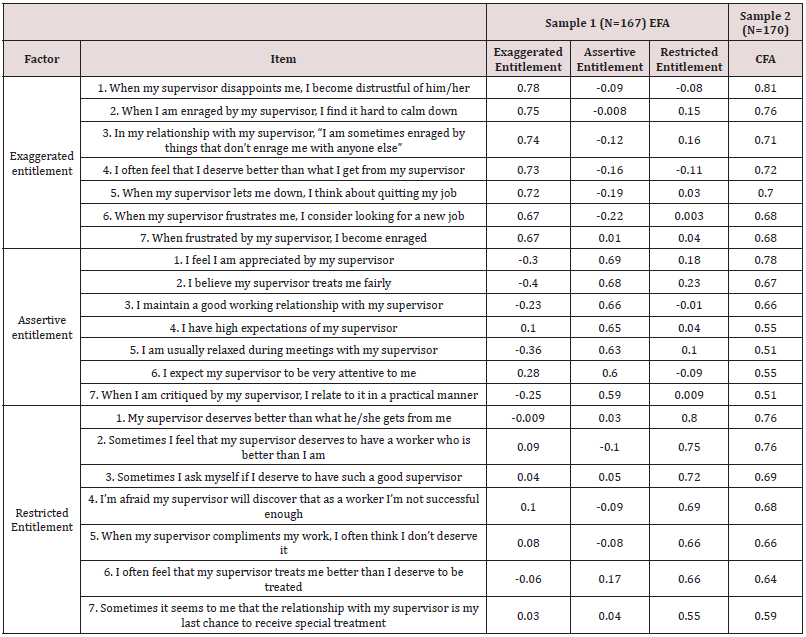

EFA was conducted to evaluate the factorial structure of the SRE-es. Principal-component analysis (PCA) with promax rotation (because the factors were assumed to be correlated) was employed in order to examine whether the 21 items could be represented by a small number of factors. To determine the number of factors to retain, three recommended criteria were considered. In terms of interpreting the extracted factors, item loadings of .40 and above are considered interpretable [20]. Only items whose primary loadings were large and whose secondary loadings were relatively small (below .30) were retained. In such cases, there was a .20 difference, or greater, between the loadings on the primary and secondary factors. The suggested number of factors to retain differed, depending on whether the K1 rule, scree test, or parallel analysis was used. The number of factors to retain as suggested by the K1 rule was seven, the scree test indicated three factors, and parallel analysis indicated three factors as well. Accordingly, we performed EFA with three factors, which accounted for 46.66% of the variance of the factors. All of the items that loaded highest on the appropriate factors had a high loading that exceeded .40. None of the secondary loadings exceeded .25. On the basis of item content, we labeled the three factors as follows: exaggerated entitlement (eigenvalue = 8.41), assertive entitlement (eigenvalue = 4.08), and restricted entitlement (eigenvalue = 3.88) (see Table 1). As such, the three-factor SRE-es structure, consisting of 21 items, was retained for further validation using CFA.

CFA with Sample 2 (N = 167)

Next, CFA was conducted to confirm the factorial structure of the SRE-es scale in a cross-validated sample, Sample 2. All three factors were allowed to correlate freely, and error terms were left uncorrelated. Table 1 presents the CFA factor loadings of the 21 items of the three-factor SRE-es. Model fit was assessed via a number of indices (i.e., chi square; degrees of freedom, df; Tucker– Lewis index, TLI; comparative fit index, CFI; root mean square error of approximation, RMSEA) as different indices reflect different aspects of model fit [21,25]. Results indicated that the model fit to the data was acceptable, χ² (347) = 965.89, p <.001; CFI = .91; TLI = .89; RMSEA = .07 (e.g., Hair et al., 2006; Hu and Bentler 1999) (Table 1).

Table 1: SREes Questionnaire - EFA factor loadings for sample 1 (N = 167) and CFA factor loadings for sample 2 (N = 170).

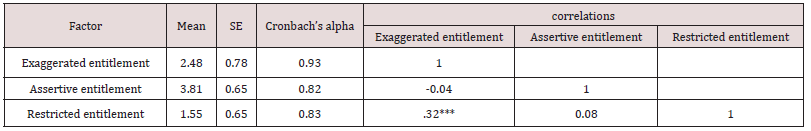

Means, standard deviations, internal consistency reliabilities, and inter-factor correlations based on the total sample (N = 337)

Sample 1 (N = 170) and Sample 2 (N = 167) were combined into a total sample (N = 337) to calculate the means, standard deviations, internal consistency reliabilities, and inter-factor correlations. Each subscale of the SRE-es was scored by calculating the mean of the items composing each subscale. The internal consistency reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients) of all three factors were good and above the recommended level, at .70 (Nunnally, 1978) (exaggerated entitlement, α = .93; assertive entitlement, α = .82; restricted entitlement, α = .83). The inter-factor correlations among the subscales of the SRE-es were found to be significant. Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and the inter-factor correlations based on the total sample (Table 2).

Table 2: Mean, Standard Deviation, Internal Consistency Reliabilities, and Inter-factor Correlations Based on the Total Sample (N = 337).

Predictive Validity

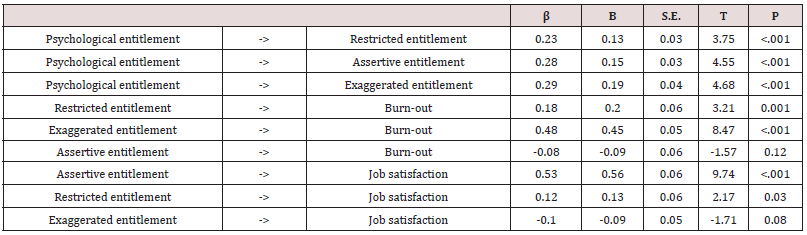

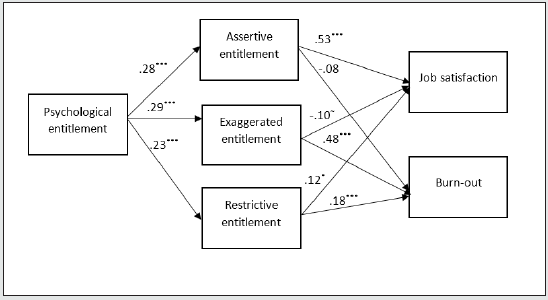

First, we calculated the correlation among research variables. The findings indicated that an exaggerated sense of entitlement toward the supervisor was positively associated with burnout (r= .54, p<.001), and negatively with job satisfaction (r= -.09, p= .07). A restricted sense of entitlement toward the supervisor was positively associated with burnout (r= .33, p<.001) and job satisfaction (r= .14, p= .01). And an assertive sense of entitlement toward the supervisor was positively associated with job satisfaction (r= .53, p<.001), and marginally significant and negatively associated with burnout (r= -.10, p= .06). Moreover, in order to assess the predictive validity of the SRE-es scale, we conducted a path analysis in AMOS- 24 (Arbuckle, 2016). Figure 1 & Table 3 presents the model findings. The model included exaggerated, restricted, and assertive sense of entitlement as exogenous independent variables, and employees’ job satisfaction and burnout as outcome variables. We controlled the variance of the unidimensional component of entitlement, in order to investigate the unique prediction of the multifactorial sense of entitlement. The model fit to the data was excellent, χ² (3) = 8.35, p= .039; NFI = .97; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .07. Exaggerated entitlement was positively associated with burnout, and marginally significantly negatively associated with job satisfaction. Restricted entitlement was positively associated with burnout and job satisfaction. Furthermore, assertive entitlement was positively associated with job satisfaction; however, its association with burnout was not significant. Together, all three entitlement factors explained 32% of the burnout variance and 31% of the job satisfaction variance. Thus, these findings indicate that the three constructs of entitlement made a significant and unique contribution in predicting employees’ satisfaction over and above the unidimensional measure of psychological sense of entitlement (Figure 1 & Table 3).

Discussion and Implications

The employee-supervisor relationship is of major importance in workplaces and organizations, and sense of entitlement among employees toward their supervisors (SRE-es) is a basic component in the dynamics of this relationship. Clearly, a better understanding of the nature of SRE-es, and its link with other relevant variables, may have significant implications both for practice and research. The goal of the current study was to assess whether a multifactorial approach, and specifically a three-factor construct of psychological entitlement, might also be applicable to the workplace domain. To achieve this goal, the original SRE questionnaire was adapted to the employee-supervisor relationship. Our findings support the results of previous studies that conceived of employees’ sense of entitlement as a multifactorial construct [5,16]. Moreover, our findings indicate that the three factorial manifestations of entitlement originally outlined and can indeed be observed in the context of the workplace and not only, as originally seen, in close personal relationships (i.e., in the context of romantic and/or adolescent-parent relationships).

A central goal of the present study was to investigate whether the three-dimensional SRE-es could predict employees’ job satisfaction and burnout, over and above the unidimensional component of entitlement. Overall, the findings of the current study suggest that a multifactorial view of sense of entitlement, encompassing both the pathological and the healthy assertion of needs and rights, offers a useful way to comprehend how attitudes of entitlement might be associated both with positive outcomes and negative outcomes, as suggested by previous studies. Our findings indicating a positive association between assertive entitlement and job satisfaction are hardly surprising. Individuals with assertive SRE-es tend to have realistic evaluations of what they are entitled to expect from others [27]. Previous research findings indicated positive associations between assertive SRE and self-esteem, secure attachment [14], self-efficacy, and life satisfaction, and a lower likelihood of emotional difficulties [12].

We also found exaggerated SRE-es to be positively linked with burnout and negatively with job satisfaction. People characterized by an exaggerated sense of entitlement tend to have unrealistic expectations that others should satisfy every need and wish they have, regardless of others’ feelings, needs, and rights [8]. Previous studies have indicated associations between exaggerated entitlement and higher levels of attachment insecurities, emotional problems, and lower levels of well-being, positive mood, and life satisfaction [7,11,19]. Given the likelihood that individuals high in exaggerated SRE are frustrated, when this attitude is activated in the context of workplace relationships, negative outcomes seem to be inevitable. For example, in the context of romantic relationships, exaggerated sense of entitlement is associated with violence and aggression among couples [17], higher divorce rates [22], and selfishness [25]. Interestingly, restricted SRE -es was positively associated with mixed outcomes, as on the one hand it was associated with burnout and on the other hand with job satisfaction. This form of entitlement seems to reflect people’s low sense of selfesteem, leading to a minimal expression of needs and wishes, as if they doubt their very right to have them [32]. As such, our results suggest that in the workplace context, employees with high levels of restricted SRE may be satisfied by the simple fact that they even have a job. However, their lack of assertiveness in standing up for their rights may lead them to experience burnout. It is important to keep in mind that a correlational study, of course, does not allow for inferences of causality. For example, although it is possible that exaggerated SRE may lead to low levels of job satisfaction, one could alternatively propose that low levels of job satisfaction might lead employees to exaggerate their demands and expectations in the workplace. Further prospective research should examine the direction of causality of the link between the different forms of SRE-es, on the one hand, and work outcomes on the other. Future research should examine the replicability and generalizability of the current findings with other workplace variables [33-45].

Implications and Limitations of the Current Study and Directions for Future Research

This study has several important implications for research and practice. First, the results from both the EFA and CFA provided support for a stable three-factor SRE-es structure. As a multifactorial scale, the SRE-es scale may be beneficial for organizational psychologists (researchers as well as practitioners) who aim to assess individual differences in employees’ sense of psychological entitlement toward their supervisors and the implications their attitudes may have for organizational outcomes. TAs such, our results indicate that the SRE-es scale may serve as a valuable scale measuring employees’ sense of psychological entitlement toward their supervisors.

The results of the present study must be considered in light of the following limitations. The study reported here represents only an initial examination of the validity of the SRE-es scale, focusing on Israeli participants. Future studies should further examine whether the SRE-es scale is applicable to other cultural settings and professional contexts, such as public sector workplaces, and among different age groups. In addition, the data collected were based on participants’ self-reports, which are susceptible to confirmation and self-serving biases [46-51]. Prospective investigations should devise innovative measures that would circumvent these concerns.

References

- Alsop R (2008) The trophy kids grow up how the millennial generation is shaking up the workplace (1st ), San Francisco: Jossey Bass, California, USA.

- Arbuckle J L (2016) AMOS 24 user’s guide. Crawfordville, FL, Amos Development Corporation, USA.

- Brouer R, Wallace A, Harvey P (2011) When Good Resources go Bad: The Applicability of Conservation of Resource Theory to Psychologically Entitled Employees. The Role of Individual Differences in Occupational Stress and Well Being Emerald Group Publishing Limited 9: 105-120.

- Brown RP, Budzek K, Tamborski M (2009) On the meaning and measure of narcissism. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 35(7): 951-964.

- Cain NM, Pincus AL, Ansell EB (2008) Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clin Psychol Rev 28(4): 638-656.

- Campbell WK, Bonacci AM, Shelton J, Exline JJ, Bushman BJ (2004) Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. J Pers Assess 83(1): 29-45.

- Cattell RB (1966) The screen test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav Res 1(2): 245-276.

- Chowning K, Campbell NJ (2009) Development and validation of a measure of academic entitlement: Individual differences in students’ externalized responsibility and entitled expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology 101(4): 970-982.

- Crowe ML, LoPilato AC, Campbell WK, Miller JD (2016) Identifying two groups of entitled individuals: Cluster analysis reveals emotional stability and self-esteem distinction. J Pers Disord 30(6): 762-775.

- Dragova Koleva SA (2018) Entitlement attitude in the workplace and its relationship to job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Current Issues in Personality Psychology 6(1): 34-46.

- Emmons RA (1984) Factor analysis and construct validity of the narcissistic personality inventory. J Pers Assess 48(3): 291-300.

- Fisk GM (2010) I want it all and I want it now!” An examination of the etiology, expression, and escalation of excessive employee entitlement. Human Resource Management Review 20(2): 102-114.

- Gerbing DW, Hamilton JG (1996) Viability of exploratory factor analysis as a precursor to confirmatory factor analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 3(1): 62-72.

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (2006) Multivariate data analysis sixth edition pearson education. New Jersey p. 42-43.

- Hare RD (1999) Without conscience: The disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. The Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Hart W, Tortoriello GK, Breeden CJ (2019) Entitled Due to Deprivation vs. Superiority: Evidence That Unidimensional Entitlement Scales Blend Distinct Entitlement Rationales across Psychological Dimensions. J Pers Assess 102(6): 781-791.

- Harvey P, Harris KJ (2010) Frustration-based outcomes of entitlement and the influence of supervisor communication. Human Relations 63(11): 1639-1660.

- Harvey P, Harris KJ, Gillis WE, Martinko MJ (2014) Abusive supervision and the entitled employee. The Leadership Quarterly 25(2): 204-217.

- Harvey P, Martinko MJ (2009) An empirical examination of the role of attributions in psychological entitlement and its outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 30(4): 459-476.

- Hochwarter WA, Meurs JA, Perrewe PL, Royle MT, Matherly TA (2007) The interactive effect of attention control and the perceptions of others' entitlement behavior on job and health outcomes, Journal of Managerial Psychology 22(5): 506-528.

- Hochwarter WA, Summers JK, Thompson KW, Perrewé PL, Ferris GR (2010) Strain reactions to perceived entitlement behavior by others as a contextual stressor: Moderating role of political skill in three samples. J Occup Health Psychol 15(4): 388-398.

- Horn JL (1965) A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 30(2): 179-185.

- Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6(1): 1-55.

- Jiang L, Tripp TM, Hong PY (2017) College instruction is not so stress free after all: A qualitative and quantitative study of academic entitlement, uncivil behaviors, and instructor strain and burnout. Stress and Health 33(5): 578-589.

- Jordan PJ, Ramsay S, Westerlaken KM (2017) A review of entitlement: Implications for workplace research. Organizational Psychology Review 7(2): 122-142.

- Kaiser HF (1960) The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological measurement 20(1): 141-151.

- Klimchak M, Carsten M, Morrell D, MacKenzie WI (2016) Employee entitlement and proactive work behaviors. J Leadersh Organ Stud 23: 387-396.

- Kline RB (2005) Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, (2nd), Guilford Press, New York, NY, USA.

- Langerud D, Jordan P (2020) Entitlement at work: Linking positive behaviors to employee entitlement. Journal of Management & Organization 26(1): 75-94.

- Laird M, Harvey P, Lancaster J, Vicki C, Carla M, et al. (2015) Accountability, entitlement, tenure, and satisfaction in Generation Y. Journal of Managerial Psychology 30(1): 87-100.

- Lee A, Schwarz G, Newman A, Legood A (2017) Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics 154: 109-126.

- Malach Pines A (2005) The Burnout Measure, Short Version. International Journal of Stress Management 12(1): 78-88.

- Miller BK, Gallagher D (2016) Examining trait entitlement using the self-other knowledge asymmetry model. Personality and Individual Differences 92: 113-117.

- Miller JD, Price J, Campbell WK (2012) Is the Narcissistic Personality Inventory still relevant? A test of independent grandiosity and entitlement scales in the assessment of narcissism. Assessment 19(1): 8-13.

- Noar SM (2003) The role of structural equation modeling in scale development. Structural equation modeling 10(4): 622-647.

- Nunnally JC (1978) Psychometric theory (2nd), New York: McGraw-Hill.

- O’connor BP (2000) SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 32(3): 396-402.

- Pines A, Aronson E (1988) Career burnout: Causes and cures. Free Press , New York.

- Pryor LR, Miller JD, Gaughan ET (2008) A comparison of the Psychological Entitlement Scale and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory's Entitlement Scale: Relations with general personality traits and personality disorders. J Pers Assess 90: 517-520.

- Smith PC, Kendall LM, Hullin CL (1969) Measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Columbus, OH: Bureau of Business Research.

- Tabachnick B, Fidell L (2001) Using multivariate statistics (4th, Intl. Student edN.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Teo T (2010) What is epistemological violence in the empirical social sciences?. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4(5): 295-303.

- Tolmacz R, Efrati Y, Ben David BM (2016) The sense of relational entitlement among adolescents toward their parents (SREap)-testing an adaptation of the SRE. Journal of Adolescence 53: 127-140.

- Tolmacz R, Mikulincer M (2011) The sense of entitlement in romantic relationships-Scale construction, factor structure, construct validity, and its associations with attachment orientations. Psychoanalytic Psychology 28(1): 75-94.

- Tomlinson EC (2013) An integrative model of entitlement beliefs. Employ Respons Rights J 25(2): 67-87.

- Watson PJ, Grisham SO, Trotter MV, Biderman MD (1984) Narcissism and empathy: Validity evidence for the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment 48(3): 301-305.

- Westerlaken K, Jordan P, Ramsay S (2017) What about ‘MEE’: A Measure of Employee Entitlement and the impact on reciprocity in the workplace. Journal of Management & Organization 23(3): 392-404.

- Whitman MV, Halbesleben JR, Shanine KK (2013) Psychological entitlement and abusive supervision: Political skill as a self-regulatory mechanism. Health Care Manage Rev 38(3): 248-257.

- Worthington RL, Whittaker TA (2006) Scale Development Research: A Content Analysis and Recommendations for Best Practices. The Counseling Psychologist 34(6): 806-838.

- Żemojtel Piotrowska M, Baran T, Clinton A, Piotrowski J, Baltatescu S, et al. (2013) Materialism, subjective well-being, and entitlement. Journal of Social Research and Policy 4(2).

- Zitek EM, Jordan AH (2019) Psychological entitlement predicts failure to follow instructions. Social Psychological and Personality Science 10(2): 172-180.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...