Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Clinical Leadership Competence in Professional Healthcare Management System: The Role of Self-Esteem, Extraversion and Interpersonal Relationship Among Clinicians in Ondo and Lagos State, Nigeria Volume 4 - Issue 5

Zubairu Dagona Kwambo1 and Dennis Uba2*

- 1Department of General & Applied Psychology, University of Jos, Nigeria

- 2Department of Pure & Applied Psychology, Adekunle Ajasin University, Nigeria

Received: January 11, 2021 Published: January 28, 2021

Corresponding author: Dennis Uba, PhD Clinical Psychology, Department of Pure & Applied Psychology, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2021.04.000197

Abstract

The perception of clinical leadership being dislocated from everyday medical practice suggests that more must be done to explain the relevance of leadership to all health care practitioners. This study examined clinical leadership competence in professional healthcare management system: The role of self-esteem, extraversion, and interpersonal relationship among clinicians in Ondo and Lagos State, Nigeria. A cross-sectional survey design was adopted in the study. Four hypotheses were formulated for the study. A total of 412 clinicians across 3 Federal and 2 State hospitals, including 4 General hospitals and 3 Health centers in Lagos and Ondo States, Nigeria was sampled using accidental sampling technique. The participants comprised of 212 (51.5%) males and 200 (48.5%) females. The ages ranged from 24 to 58 with a mean of 38.19 years and SD of 9.52. Relevant data were gathered through the use of validated questionnaire which comprised 5 sections: Socio-demographic information, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Relationship Assessment Scale, Big Five Personality Inventory and Clinical Leadership Competency Framework.

In order to determine the extent and direction among the study variables, Pearson Product Moment Correlation (PPMC) analysis was conducted. Multiple regression analysis was then used to test hypothesis 1, 2, 3 and 4. Results from the study showed that selfesteem did not predict clinical leadership competence (β = -.00; t = .06; p > 0.05). Interpersonal relationship showed an inverse relationship with clinical leadership competence (β = -.13; t = -2.74; p < 0.01). Extraversion inversely predicted clinical leadership competence (β = -.17; t = -3.69; p < 0.01). Based on the contribution of all the independent variables (self-esteem, interpersonal relationship, and extraversion) to the prediction of clinical leadership competence, the outcome of the study indicated that all the independent variables when pulled together yielded a multiple R of .239 and R2 of .057 [F = (3, 412) = 8.195, p < 0.01]. Based on the findings of this study, the researcher recommended that colleges of medicine, schools of nursing and other various institutes of healthcare management under the Ministry of Health in Nigeria should take adequate steps to inculcate clinical leadership structures that would situate clinicians in leadership positions.

Keywords: Clinical Leadership; Self-esteem; Extraversion; Interpersonal relationship word count: 353

Introduction

Background to the study

Healthcare leadership is a critical and far-reaching concept [1]. The best leaders have been those with vision. The practice of leadership is often more of an art than it is science [2]. Leadership within healthcare practice has been principally the domain of medical doctors. However, healthcare outcomes are a function of the involvements of healthcare workers such as, nurses, social workers and psychologists [3]. Making clinician’s organizational leaders is a huge, intricate and costly task. Is it worth it? Especially given the many competing demands on clinician’s time? They and others will rightly seek evidence of the link between clinical leadership competence and the organization’s performance, in both clinical and financial terms [4]. Proof of a direct correlation will remain elusive, thanks to the inherent complexity of health systems, whose performance is affected by multiple, overlapping tasks in healthcare management. Nonetheless, diverse and growing bodies of researchers have suggested the enormous impact of clinical leadership in healthcare professional practice [5-8].

The Institute of Medicine (2001) reported that healthcare organizations world over, who have incorporated the clinical leadership practices have witnessed tremendous growth. For example, Kaiser Permanente, a large, integrated United States healthcare provider operating in several states in the late 1990s, was struggling with declining clinical and financial performance, and was losing some top clinicians to private practice and rival organizations. A new CEO (a pediatric plastic surgeon) made clinical leadership an explicit driver of improved patient outcomes, defining the role of the clinician as “healer, leader and partner” and revamping Kaiser’s leadership development programmes for doctors [8,9]. However, within five years of adopting this new approach, Colorado had become Kaiser’s highest-performing affiliate on quality of care and a beacon of excellence within the United States healthcare; patient satisfaction grew significantly; staff turnover fell dramatically; and net income rose from a deficit budget to $87million (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Hence, need arises for healthcare providers with a diverse and specific set of competencies [10-12]. However, the question hinges on what set of competencies will produce qualitative clinical leadership competency? Clinical leadership is a readily used term to describe doctors and other health care mavens as leaders within the health service but has thus far been less well defined [13]. Clinical leadership involves influencing and motivating others to deliver clinically effective care by demonstrating clinical excellence, providing support and guidance to colleagues through mentorship, supervision and inspiration [14]. Clinical leadership can also be perceived as positioning clinicians at the core of determining and overseeing clinical services, so as to deliver first-rate outcomes for patients and populations, not as a one-off task or project, but as a core part of clinicians’ professional identity and concern [15,16]. The National Co-coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organization suggest that effective clinical leadership is pivotal in ensuring that improvement in healthcare is not only on the agenda of all National Health Scheme organizations but becomes part of their working structure. Transforming healthcare is everyone’s business with the provision of high-quality care being at the heart of everything [17]. Creating a culture of visible commitment to patient safety and quality requires clinical and professional leaders to work together so that health care systems can meet the healthcare challenges of the future [18]. A clinician is a healthcare practitioner such as a psychologist, physician, psychiatrist, occupational therapist or nurse, involved in clinical practice, as distinguished from one specializing in research or that works as primary care giver of a patient in a hospital setting; or clinic setting [19-25]. In other words, a clinician can be viewed as a health care professional that practices at a clinic [26]. While clinical leaders are clinicians who has direct responsibility or influence on patient care at ward, unit or team level which is applicable also to primary care and general practice settings [27]. A clinical leader integrates research evidence into practice, leads efforts to improve patient care, acknowledged as a leader in all situations and is an advocate for transforming the health system and implementing best practice [16].

Although, clinical tradition and training make the idea of clinical leadership conflicting to many clinicians, this perception have been regarded as rather detrimental to clinical leadership approaches [17,28]. The conventional view is that doctors and nurses should look after patients, while administrators look after organizations [29]. Yet several pioneering healthcare institutions have turned this assumption on its head by advocating and achieving outstanding performance [30]. Clinical Leadership is about more than simply appointing people to particular positions [30]. Rather, it is about recognizing the diffuse nature of leadership in health care organizations, and the importance of influence as well as formal authority [31-35]. Clinical leadership is not a new concept and the need to optimize leadership potential across the healthcare professions and the critical importance of this to the delivery of excellence and improved patient outcomes, is now increasingly echoed by clinicians, managers and politician’s world over [36,37]. Report that clinical leadership differs from management responsibility in that, leadership is thought of as undertaking and showing the way by helping to shape and manage clinical services for the better of patients and staff. Whereas a manager might be expected to regularly deal with relatively routine tasks, a clinical leader also uses their expertise and evidence to provide solutions to clinical problems [36].

The perception of leadership being dislocated from everyday medical practice suggests that more must be done to explain the relevance of leadership to all health care practitioners from a variety of backgrounds in order to provide the type of expert leadership they advocate [36]. There has been increasing recognition for the role that clinicians can provide in meeting the demands for a better health care delivery system [38]. To respond effectively within some predetermined health budget clinicians must not merely be at the forefront of treatment but also integrated into health care decision and policy making [39]. Define self-esteem as when one has a good opinion of oneself. Self-esteem is the way people think about themselves and how worth-while, they feel [40]. Assert that when a person's self-esteem is high, he tends to be motivated and performs his job or task better. Task here refers to specific piece of labour/work to be done as a duty required by an authority or delegated responsibility [2,3]. Self-esteem is a state of mind, it is the way you think and feel about yourself having high self-esteem means having feelings of confidence, worthiness, and positive regard for one’s self [40,11]. People with high self-esteem often feel good about themselves, feel a sense of belonging, self-respect and appreciate others [41,15]. People with high self-esteem tend to be successful in life because they feel confident in taking on challenges and risking failure to achieve what they want [42].

Asserted that clinicians with recognizable self-esteem have more energy for positive pursuits because their energy is not wasted on negative emotions [4], feelings of inferiority or working hard to take care of or please others at the expense of their own self-care [43]. Posits that self-esteem is believed to be relevant to the individual’s optional adjustment and functioning. However, an ingrained skepticism emerges among clinicians about the value of spending time on leadership, as opposed to the evident and immediate value of treating patients [1,15,44] suggested high self-esteem indicates a person respect for self and does not consider him or herself superior to others, recognizes self-limitations, and expects to grow and improve. Low self-esteem implies self-rejection or self-contempt, feeling disagreeable about oneself and wishing it were otherwise (Table 1). Rosenberg explained self-concept is not a collection but an organization of parts, pieces, and components and that are hierarchically organized and interrelated in complex ways and [45] describe global self-esteem to be an individual’s positive or negative attitude toward the self as a totality, which is strongly related to overall psychological wellbeing.

Self-esteem has not been shown to predict the quality or duration of relationships among spouses [11]. Yet high self-esteem makes people more willing to speak up in groups and to criticize group's approach [46,47] refer that leadership does not stem directly from self-esteem, but self-esteem may have indirect effects. Furthermore, people with high self-esteem show stronger in-group favoritism, which may increase prejudice and discrimination [48-50]. Extraversion is also one of the personality characteristics that have found in some studies to be more characteristic of leaders compared to non-leaders [7]. Extraversion refers to interest in or behaviour directed toward others or one’s environment rather than oneself [51]. One of the most consistent results in the study of leadership, emotion and personality is that extraversion is having an indirect effect on [52]. Leaders who are gregarious, active and outgoing tend to experience more pleasant emotion than those leaders who are quiet, inactive and introverted this does not portend leadership effectiveness, but this assertion cannot be generalized in that this signify differing results among those in healthcare practice [53]. Individual differences in leadership performance have been linked to differences in personality and relationships especially with leader’s span of control [48]. Research has shown that personality plays an important role in shaping who earns leader status in work groups [54-60] by signaling competence and shaping performance expectations when groups first form [61]. In particular, extraverted members tend to express confidence, dominance, and enthusiasm, and so are attributed with high status and frequently selected for leadership positions [62-65]. Conversely, neurotic members tend to express anxiety, withdrawal, and emotional volatility, earning lower status and rarely emerging as leaders [66].

Clinicians in general, therefore have considerable opportunity to influence patients' attitudes and behaviours in relation to their treatment, rehabilitation, and recovery process [67]. As nursing requires a focus on therapeutic and interpersonal interaction between the clinician and the patient, it is likely that the attitudes and interpersonal practices the clinician brings to this interaction will influence his/her care of the patient [68,61] suggested that it is potentially useful to study the nurse/ doctor, nurse/patient interaction by measuring aspects of this interaction through the use of an instrument that specifically examines nursing approach towards a particular type of patient and improve understanding of interpersonal attitudes and practices which enhance the ability of nurses to provide problem focused care that is appropriate to the patient. A clinical leader is perceived as proficient, well-trained, and knowledgeable health care professional who have the vision to see improvements to services or who is able to address limitations within the health system and share their vision with their fellow practitioners [69]. Extensively, doctors who were able to use influence or change management skills are considered most likely to be successful in turning a vision into reality [70]. However, the issue bothers around which set of competencies will produce qualitative clinical leadership? Hence, this research tends to fill this gap by investigating self-esteem, extraversion along with interpersonal relationship as predictors of clinical leadership among clinicians in Ondo and Lagos State, Nigeria.

Statement of the Problem

In the past few years, the healthcare industry in Nigeria have witnessed strikes like the one recently embarked upon by the Nigerian Medical Association in conjunction with the Nigerian Pharmacological Society (NPS) who embarked on an indefinite strike to press on their 24 point demand with the government of Nigeria chief among these demands, is the demand that medical practitioners should direct the affairs of all healthcare organization in Nigeria as obtainable in other developed countries of the world [17]. Although, these demand and policies are aimed at enhancing the safety of patients and the welfare of medical practitioners to better improve the services of the health sector and the welfare of hospital employees to compete favorably in Africa and the global system [15,26] noted that the clamour would create enormous challenges for those hospitals and healthcare organizations who are not equipped to practice clinical leadership. Some of the challenges identified by this author are: personality characteristics of clinicians and the role in plays within the leadership spectrum, lack of leadership training skills in the curriculum of health workers in the industry, the demands of leaders by developing the right personality needed for leadership and closer monitoring by the regulatory body (Table 2). These developments will make most healthcare organizations in Nigeria lay emphasis on service delivery which is in the best interest of patients.

While the primary focus of regulation for clinicians is on their professional practice, all clinicians, registered or otherwise, work in systems and most within organizations. It is vitally important that clinicians have an influence on these wider organizational systems and thereby improve the patient experience and outcome [71]. Clinicians have an intrinsic leadership role within healthcare service and have a responsibility to contribute to the effective running of the organization in which they work and to its future direction [27]. Therefore, the development of leadership competency as an integral part of a clinician’s training will be a critical factor. Delivering services to patients, service users, care givers and the public is at the heart of the Clinical Leadership Competency Framework. Clinicians work hard to improve services for people [46]. Furthermore, Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Health has observed that the lack of performance of the country’s health system is attributable to the weakness in leadership role of government in health [72]. In an attempt to address this situation a leadership and governance training workshop was held in August 2010 in Abakaliki, the capital of Ebonyi State southeastern Nigeria. This workshop recommended that no matter how adequate Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Health or the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA) policy reforms are, such policies may not yield desired results if the hospital employees who are to execute the policy are not adequately trained in leadership practices [73]. The desire for improved healthcare and sustenance of the industry in Nigeria might become short-lived if adequate attention is not given to the factors responsibility for clinical leadership. In the last decade, clinical leadership has been a subject of investigation in the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States of America [74,75]. However, despite the growing body of literature on clinical leadership, only few African studies have explored clinical leadership [17,28,46]. In particular, there are relatively no considerable empirical studies on the influence of self-esteem, interpersonal relationship, and extraversion on clinical leadership among clinicians in Nigeria. To this date, arguably, no Nigerian study has been found to empirically investigate the predictors of clinical leadership.

In view of this gap, this study investigates the influence of self-esteem, extraversion, and interpersonal relationship on clinical leadership among clinicians in Ondo and Lagos State, Nigeria. Exploring clinical leadership from this angle might help proffer lasting solution to clinician’s psychosocial requirement for clinical leadership in Nigeria. In light of these it would be pertinent to ask some relevant question:

- Would self-esteem predict clinical leadership competency?

- Would extraversion predict clinical leadership competency?

- Would interpersonal relationship predict clinical leadership competency?

- Would self-esteem, interpersonal relationship, and extraversion predict clinical leadership competency?

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship among self-esteem, extraversion, and the influence of interpersonal relationship on clinical leadership. However, the specific major purpose of this study is to:

- Examine the predictive role of self-esteem on clinical leadership among clinicians in Ondo and Lagos State.

- Determine the predictive role of extraversion on clinical leadership among clinicians in Ondo and Lagos State.

- Access the predictive role of interpersonal relationships on clinical leadership among clinicians in Ondo and Lagos State.

- Ascertain the combined predictive roles of self-esteem, extraversion and interpersonal relationships on clinical leadership among clinicians in Ondo and Lagos State.

The quality of interpersonal relationship has been found to predict treatment adherence and outcome across a range of patient diagnoses and treatment settings [57] and may even be considered a curative agent in its own right [11]. In community psychiatry, community mental health teams provide comprehensive care programmes for people with severe mental illness. Although there is a shared caseload in assertive community treatment [38] one named person is usually responsible for keeping in close contact with the patient and coordinating care. Priebe suggests that the relationship between a patient and a clinician takes centre stage of managed care delivery in community mental health services. A study by McKinsey and the London School of Economics, in 2008, involving over 170 general managers and heads of clinical departments in the United Kingdom National Health Service (NHS), found that hospitals with the greatest clinician involvement in management scored some 50% higher on key measures of organizational performance than hospitals with low clinical leadership [29]. Among the growing base of academic evidence, a National Health Service study found that in 11 examples of attempted service improvement, organizations with stronger clinical leadership competence were more successful in delivering change (National Co-coordinating Centre for National Health Service Delivery and Organization). National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organization found an ingrained skepticism among clinicians about the value of spending time on leadership, as opposed to the evident and immediate value of treating patients. Participants explained that playing an organizational-leadership role is not seen as vital either for patient care or their own professional success and therefore seemed irrelevant to the self-esteem and careers of clinicians. Moreover, many participants expressed discomfort with knowing that the impact of clinical leadership is often difficult to prove.

According to Felfe and Schyn extraversion seems to influence the perception of leadership. Felfe and Schyns warn that feedback of followers high in extraversion tend to be biased positively, in contrast to feedback from introverts because of the positive correlation of extraversion with acceptance. According to Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (a measurement instrument of human behaviour based on the studies of Carl Jung), the categorization of extraversion is a reflection of an individual’s preference for interacting with the world [17]. Extroverts are energized by the outer word of people, places and things. Whereas introverts are energized by their inner world of ideas, thoughts and concepts [52], another definition of extraversion, ‘refers to the extent to which individuals are sociable, loquacious, energetic, adventurous and assertive [71]. This risk-taking behaviour of extroverts may be very useful in some fields where taking risks is an essential part of everyday decision-making [8,16]. Despite these contributions in the reviewed studies, there is a dearth in the examination of psycho-social and personality studies on clinical leadership in Nigeria. As a matter of fact, there had never been any empirical study on clinical leadership in Nigeria. In view of this gap in literature, this study therefore explored the joint and independent influence of self-esteem, interpersonal relationship, and extraversion on clinical leadership among clinicians in south-western Nigeria.

Research Hypotheses

a) Self-esteem will independently significantly predict

clinical leadership.

b) Interpersonal relationship will independently

significantly predict clinical leadership.

c) Extraversion will independently significantly predict

clinical leadership.

d) Self-esteem, interpersonal relationship, and extraversion

will jointly significantly predict clinical leadership.

Method

Research Design

A cross-sectional survey design was adopted in the study. Moreover, variables of this study were not actively manipulated. The dependent variable is clinical leadership. The predictor variables are self-esteem, interpersonal relationship and extraversion.

Research Setting

Employees in the health industry in Lagos and Ondo states metropolis, Nigeria constitute the population of this study because healthcare workers in Lagos and Ondo State are strategically located in the hub of the most populous nation in Africa. The pluralistic, commercial, and strategic nature of Lagos and Ondo states informed the choice of hospitals used in the study.

Participants

A total of 412 employees across 3 federal and 2 state hospitals, including 4 general hospitals and health centers in Lagos and Ondo metropolis, Nigeria were sampled using accidental sampling technique. The federal and state hospitals, including general hospitals and health centres were also selected. The participants comprised of 212 (51.5%) males and 200 (48.5%) females. The ages ranged from 20 to 59 with a mean of 38.19 years and SD of 9.52. Also, 106 (25.7 %) of the participants were single, 255 (61.9%) were married, 29 (7.0%) were widowed, and 19 (4.6%) were divorced. Their qualification also varied; 5 (1.2%) had WAEC/GCE, 30 (7.3%) had NCE/OND, 137 (33.3%) HND/B.Sc., Masters 207 (50.2%) and PhD 28 (6.8%). Their job position revealed that 161 (39.1%) were of junior cadre and 245 (59.5%) were of senior cadre. In addition, their job tenure ranged from 1 year to 33 years with a mean of 8.58 years and SD of 6.345.

Instrument

Relevant data were gathered through the use of validated questionnaire which comprises of four sections (A-E). Section A: Socio-demographic information. These include age, gender, marital status, job position, job tenure and academic qualification. Section B, The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. The Rosenberg self-esteem scale is a widely used self-report instrument for evaluating individual self-esteem, 10-item scale that measures global self-worth by measuring both positive and negative feelings about the self. The scale is uni-dimensional. All items are answered using a 4-point Likert type scale format ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Scoring: Items 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 are reverse scored. Give “Strongly Disagree” 1 point, “Disagree” 2 points, “Agree” 3 points, and “Strongly Agree” 4 points. The scores are on a continuous scale. Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. Samples items included: ‘‘I am able to do things as well as most other people’’. Byrne showed that the RSES had adequate internal reliability, and test-retest correlation of 0.61 over a 7-month period in Ontario, Canada. Reported a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.79 and [12] reported a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.86, among health workers. and he reported a Cronbach’s Alpha of the Rosenberg scale coefficient of .92 showing good internal consistency using Nigerian Sample.

Section C contains the Relationship Assessment Scale developed by Hendrick (1988) was a 7-item scale designed to measure general relationship satisfaction. Respondents answer each item using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). The instrument takes a critical look at a central construct in relationship satisfaction. Eight well-validated self-report measures of relationship satisfaction. Scoring: Items 4 and 7 are reverse-scored. Samples items included ‘‘in general, how satisfied you with your work relationship are’’. ‘‘How good is your relationship with your co-workers compared to most of the other employees’’. Among Nigerian samples, Iheonunekwu, Anyatonwu, & Eze reported a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.88. In the present study, a Cronbach’s Alpha of .589 was obtained for the scale. Respondents answer each item using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction).

Section D contains the measures of extraversion from the Big Five Personality Inventory. The instrument used for collection of data for extraversion was the big five personality traits questionnaire, coined by [41]. However, only the section measuring extraversion was used in the study and not the composite sections of the instrument [61]. The instrument measured facets of (and correlated trait adjective) extraversion including gregariousness (sociable), assertiveness (forceful), activity (energetic), excitement-seeking (adventurous), positive emotions (enthusiastic), and warmth (outgoing). Samples items included ‘‘I like to start most conversations’’. ‘‘I talk to a lot of different people at gatherings and events’ and he reported Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients were between 0.66 and 0.87 and the inventory was validated through criterion-related validity with coefficients between 0.65 and 0.76.

Section E contains the Clinical Leadership Competency Framework (CLFC): The Clinical Leadership Competency Framework was created with the agreement of the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement and the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. The Clinical Leadership Competency Framework which was created developed and is owned jointly by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (Department of Health, 2001). The scale is a 39 item Likert type scale, divided into 5 distinct but interrelated domains, i.e. Demonstrating Personal Qualities (DPQ), Working with Others (WWO), Managing Services (MS), Improving Services (IS) and Setting Direction (SD). Sample item include: ‘‘I apply my learning to practical work’’, ‘‘I take action to improve performance’’, ‘‘I take responsibility for embedding new approaches into working practices’’. Malcolm, Wright, Barnett & Hendry obtained Cronbach Alpha of 0.78 and [45] obtained Cronbach Alpha of 0. 77. In the present study, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of .791 was obtained. However, there are no studies yet in Nigeria that has empirically studied the concept of clinical leadership competency.

Procedure

In order to get the clinicians that participated, permission and ethical approval was sought and obtained from the ethical review committee of the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, Lagos. In a bid to get clinicians to participate in the study, approval was sought and obtained in form of informed consent before they were selected for the assessment. The respondents were adequately informed about the nature of the study and its benefits. The purpose of the study was explained to the participants as they were also given assurance of confidentiality and anonymity of their identities and responses. In addition, the respondents were told that there was no right or wrong answers, and as such should try to be honest as possible in their responses. The choice of hospitals was arrived at after the researcher sought and obtained permission and was granted by the authorities of these hospitals which included a letter from the Ethic Review Board, Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, in Lagos. Using accidental sampling technique, the researcher administered four hundred and thirty questionnaires to clinicians across various disciplines that consented in such a way that averages of 45 copies of questionnaire were administered per hospital. The reason for using accidental sampling technique and not randomization was because most hospital employees are always busy and their job-schedule (shift rotation) situations in most hospitals and clinics did not allow for a more rigorous sampling technique. So, the only way to get sustainable participants is by using this non-probabilistic method. Although, four hundred and thirty (430) copies of questionnaire were administered but only four hundred and twelve (412) copies of questionnaire were found usable for the analysis. This yielded a response rate of 95.8%.

Inclusion Criteria

Eligibility to participate in the study included all qualified employed resident/consultant clinicians which comprises of Psychiatrists, General Practitioners, Surgeons, Neuro-surgeons, Orthopedics, Ophthalmologists, Pharmacist, Occupational Therapists, Clinical Psychologists, Psychiatric Nurses, Laboratory Analysts, Social workers and Interns (Medicine, Pharmacy and Psychology) who have spent not less than 6 months and who are in direct contact with patient or who provide healthcare for inpatients and outpatients in managed care institutions.

Exclusion Criteria

The respondents that were ineligible or excluded from the study comprised those classified as outliers who included, retired healthcare practitioners, healthcare artisans and those chronologically less than 18 years of age, clinicians with less than six-month experience, laboratory workers, ambulance drivers, administrative staffs, hospital domestic workers and all nonpracticing healthcare professionals.

Data Analysis

In order to determine the extent and direction of associations among the study variables, Pearson Product Moment Correlation (PPMC) analysis was conducted. Multiple regression analysis was then used to test hypothesis 1, 2, 3 and 4. Some of the sociodemographic variables were codified. For example, gender was coded male 0, female 1. Marital status was coded single 0, married 1, widow 2 and divorce 3. Job position was coded junior 0, senior 1. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 20.0 Wizard.

Results

Test of relationship among the study variables

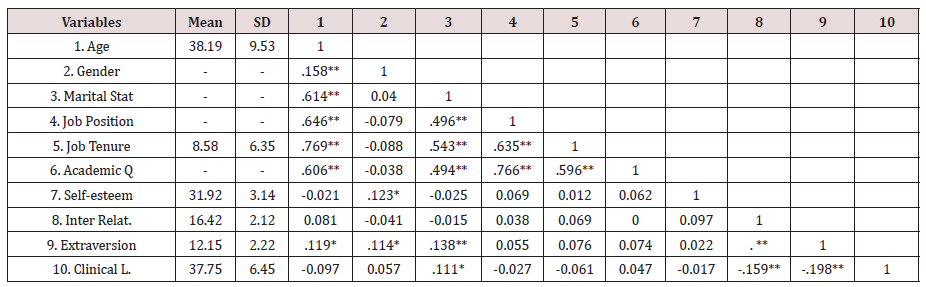

The first analysis involved inter-correlations of all the variables of the study. The result Results in Table 1 indicated that age, gender, job position, job tenure and academic qualification had no significant relationship on clinical leadership. However, marital status depicted significant relationship with clinical leadership. Table 1 showed that self-esteem did not have a significant relationship with clinical leadership [r (412) = -.017; p > 0.05]. This implies that self-esteem does not have any relationship with clinical leadership. Interpersonal relationship had significant negative relationship with clinical leadership [r (412) = -.159; p < 0.01]. This indicates that clinicians who reported high interpersonal relationship develop low clinical leadership. Similarly, extraversion had significant negative relationship with clinical leadership [r (412) = -.198; p < 0.01]. This imply that clinicians who reported high extraversion show low clinical leadership competency.

Table 1: Correlation Matrix Showing the Mean, SD and Inter-Variable Relationships among Variables of the Study.

**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, N=412. Key: Marital Stat. = Marital Status, Academic Q. = Academic Qualification, Inter Relat. = Interpersonal Relationship, Clinical L. = Clinical Leadership

Test of hypotheses 1, 2, 3 and 4

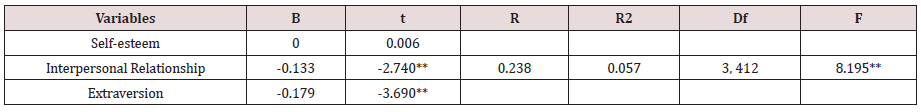

In order to test hypothesis 1, 2, 3 and 4, multiple regression analysis was conducted. The result is presented in Table 2 Results in Table 2, showed that self-esteem did not significantly predict clinical leadership (β = -.00; t = .006; p > 0.05). This means that self-esteem of clinicians will not determine clinical leadership competence. Therefore, hypothesis 1 was rejected. Interpersonal relationship showed an inverse relationship with clinical leadership (β = -.13; t = -2.74; p < 0.01), it implies that clinicians who reported high on interpersonal relationship showed low clinical leadership competency compared to those who scored low on interpersonal relationship. The result confirmed hypothesis two. Therefore, hypothesis 2 was confirmed. Extraversion inversely predicted clinical leadership (β = -.17; t = -3.69; p < 0.01). This implied that clinicians who reported high on extraversion showed lower clinical leadership competency compared to clinicians who scored low on extraversion. This result did confirmed hypothesis 3. Therefore, the hypothesis was accepted.

Table 2: Summary of Multiple Regression Analysis Showing the Contributions of Self-Esteem, Interpersonal Relationship and Extraversion to Clinical Leadership.

Note: ***p < 0.01; N = 412

Hypothesis 4, which was based on the contribution of all the independent variables (self-esteem, interpersonal relationship, and extraversion) to the prediction of clinical leadership, the outcome of the summary in Table 2 signifies that all the independent variables when pulled together yield a multiple R of 0.239 and R2 of .057 [F = (3, 412) = 8.195, p < 0.01]. This is an indication that all the independent variables contributed 5.7% of the variance in clinical leadership. Meanwhile, other variables not considered in this study therefore accounts for 94.3%.

Discussion

The study examined the influence of self-esteem, interpersonal relationship, and extraversion on clinical leadership among clinicians in Ondo and Lagos State, Nigeria. In hypothesis 1, the result showed that self-esteem did not significantly predict clinical leadership. Therefore, the hypothesis was rejected. The result of this study supported the findings [21] and according to these authors self-efficacy, self-confidence and self-esteem does not directly contribute to leader success. Rather, they suggested that it is the individual’s belief regarding his or her capabilities to successfully perform the leadership task that is the key causal factor. Also, this result corroborates with the findings [45] and these authors stated that laboratory studies have generally failed to find that self-esteem predicts good task or leadership performance with the important exception that high self-esteem facilitates persistence after failure. An explanation for this is that leadership does not stem directly from self-esteem, but self-esteem may have indirect effects [5]. Clinicians with high self-esteem show stronger in-group favoritism that may lead to or increase prejudice and discrimination that are detrimental to healthcare management. Also, self-esteem is heavily invested with feelings about the self, as specific facets of selfesteem include a variety of self-related thoughts whereas, clinicians are trained to work as unit where competence is commended, and personal identity is consigned to the background [70].

In addition, the result revealed that interpersonal relationship significantly negatively predicted clinical leadership. As a result, hypothesis 2 was not confirmed. This implies that clinicians with high interpersonal relationship predict low clinical leadership competence. This is viable because studies and [11,16] have revealed that interpersonal relationship between clinicians and patients are ethically restricted because the association is a therapeutic relationship for example, the relationship between the clinician and client differs from both a social and an intimate relationship in that the clinician maximizes his or her communication skills, understanding of human behaviors, and personal strengths to enhance the client’s growth.

Further reason for the negative correlation between interpersonal relationship and clinical leadership can be tied to the ingrain code of ethics and standards of practice for healthcare quality professionals which stipulates that healthcare professionals must always maintain the highest standards of professional conduct by not permitting relationships interpersonal or otherwise to influence the free and independent exercise of professional judgment on behalf of patients [56]. The results of the current study revealed that extraversion negatively predicted clinical leadership which corroborated with the findings of Redfern [9]. who found a significant negative association between extraversion and clinical leadership? Research on the “dark sides” of extraverted behaviors finds that with experience working together, peers interpret extraverts as poor listeners who are unreceptive to input from others [16]. For example, Opayemi and Balogun determined that when subordinates are proactive (i.e., they voice constructive ideas, take charge to improve work methods, and exercise upward influence), groups with more extroverted leaders are less effective due to heightened competition and conflict.

Conclusion

Based on the findings, the study has empirically demonstrated that clinicians who perceived a diminish sense of self-esteem, low interpersonal relationship and extraversion showed higher tendency to demonstrate clinical leadership competence than their counterparts. Moreover, the results revealed that hospital employees who have high self-esteem showed lower tendency to exhibit clinical leadership competence. The result of this study also showed that all the independent variables (self-esteem, interpersonal relationship, and extraversion) jointly predicted clinical leadership. Conclusively, findings of this study established that self-esteem, interpersonal relationship, and extraversion jointly exert significant influences on clinical leadership competence among clinicians.

Implications of the findings

Findings of the study have some direct practical implications for management and boards of directors in ministries of health in government owned hospitals in Nigeria and Africa. The findings of this study also have practical implications for reviewing and updating Nigerian hospital reforms and training manual, specifically in relations to teaching, training of hospital employees. It is therefore suggested that hospital management should include measure of clinical leadership as part of assessment tools, and academic course during training. Clinical leadership training should also form an important area of concentration in colleges of medicine, and schools of nursing.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, the researcher recommends as follows: Colleges of medicine and various schools of Nursing under the Ministry of Health in Nigeria should take adequate steps to inculcate clinical leadership structures that suit and encourages the cultural and environmental demands of clinical leadership competencies. In other words, clinicians who work in healthcare environments in Nigeria shall acquire career development possibilities and leadership training like those in the United Kingdom (UK), and central Europe who are already reaping the dividends of clinical leadership competency. Since clinicians interact and work directly with patients and hold the interest of the patient the most. The researcher therefore recommends that the Nigeria healthcare reforms and policies should be reviewed, specifying issues relating to enrollment, conscription, and training of clinicians. It is therefore recommended, that hospital management in Nigeria should include measure of clinical leadership competency as part of their training and assessment tools during enrolling in medical colleges, and schools of nursing. This may help hospital employee’s deal with work pressures, physician-nurse relationship, medical team structure and functional responsibility. Healthcare practice needs evidences that are proved by research outcomes. Integration of research evidence into clinical leadership performance is essential for the delivery of high-quality clinical care. Leadership behaviors of doctors, psychologists, nurses, especially, managers and administrators have been identified as important to support research use and evidence-based practice. Yet, minimal evidence exists indicating what constitutes effective clinical leadership competency for this purpose or what kinds of interventions help clinical leaders to successfully influence research-based care. It is recommended that research centred on these areas should be intensified.

References

- Academy of Royal Medical Colleges & NHS Institute (2007) Enhancing engagement in clinical leadership. NHS Leadership Academy.

- Adeyemo DA (2002) Job involvement, career commitment, organizational commitment and job satisfaction of the Nigerian police. A multiple regression analysis. Journal of Advance studies in Educational management 5(6):35-41.

- Akubundu DU (2008) Motivation and productivity in the library.

- Alavi HR, Askaripur MR (2003) The relationship between self-esteem and job satisfaction of personnel in government organizations. Public Personnel Management 23(4): 591-598.

- Anderson C, Kilduff GJ (2009) Why do dominant personalities attain influence in face-to-face groups? The competence-signaling effects of trait dominance. J Pers Soc Psychol 96: 491-503.

- Anderson C, John OP, Keltner D, Kring AM (2001) Who attains social status? Effects of personality and physical attractiveness in social groups. J Pers Soc Psychol 81:116-132.

- Arnold J (2005) Work psychology. Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education Limited 428-429.

- Ashford J, Eccles M, Bond S, Hall LA, Bond J (1999) Improving health care through professional behaviour change: Introducing a framework for identifying behaviour change strategies. British Journal of Clinical Governance 4(1):14-23.

- Ayodele KO (2013) The influence of Big-Five personality factors on lecturers-student interpersonal relationship. African symposium. Journal of the African Educational Research Network.

- BAMM (2004) Making Sense: A career structure for medical management, Stockport: The British Association of Medical Managers.

- Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD (2003) Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest 4:1-44.

- Berger J, Cohen BP, Zelditch M (1972) Status characteristics and social interaction. American Sociological Review 37:241-255.

- Berger J, Fisek HM, Norman RZ, Zelditch M (1977) Status characteristics and social interaction: An expectation states approach. New York: Elsevier.

- Blascovich J, Tomaka J (1993) Measures of self-esteem: In JP Robinson, PR Shaver and L.S. Wrightsman (Eds.) measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. Third Editor. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research pp.15-17.

- Bunmi O (2009) Self-esteem and self-motivational needs of disabled and non-disabled: A comparative analysis. Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences 1(2):449-458.

- Busari J, Koot B (2007) Quality of clinical supervision as perceived by attending Doctors in University and district teaching hospitals. Med Educ 41(10):957-964

- Busari JO (2013) Management and leadership development in healthcare and the challenges facing physician managers in clinical practice. The International Journal of Clinical Leadership 17(4):211-216.

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL (2005) Personality development: Stability and change. In: ST Fiske, AE Kazdin, DL Schacter (Eds.), Annual Review of Psychology. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews, 56: 453-484.

- Catty J (2004) The vehicle of success: Theoretical and empirical perspectives on the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and psychiatry. Psychol Psychother 77:255-272.

- Costa PT, McCrae, RR (1992a) Four ways five factors are basic. Personality & Individual Differences 13(6):653-665.

- Crabtree S (2004) Getting personal in the workplace: Are negative relationships squelching productivity in your company? Gallup Management Journal 1-4.

- Dash P, Garside P (2007) Wanted: Doctors to help design services. Journal of Health Service 7 117(6059): 20-21.

- Denis JL, Lamonthe L, Langley A, Valette A (1999) The struggle to redefine boundaries in healthcare systems. In: D Drock, M Powell, C Hinings (Eds.) Restructuring the professional organization. Routledge, London.

- Department of Health (2001) NHS Leadership Qualities Framework.

- Dickinson H, Ham C (2008) Engaging Doctors in leadership: Review of the literature health services management centre. University of Birmingham, UK.

- Empey D, Peskett S, Lees P (2002) Medical leadership. British Medical Journal 325: S191.

- Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) (2004) Health sector reform programme: Strategic thrust with a logical framework and a plan of action 2004-2007.

- Felfe J, Schyns B (2006) Personality and the perception of transformational leadership: The impact of extroversion, neuroticism, personal need of structure, and occupational efficacy. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 36(3): 715-716.

- Fitzgerald L (1994) Moving clinicians into management. A professional challenge or threat? J Manag Med 8(6): 32-44.

- Flynn FJ, Reagans RE, Amanatullah ET, Ames DR (2006) Helping one’s way to the top: Self-monitors achieve status by helping others and knowing who helps whom. J Pers Soc Psychol 91(6): 1123-1137.

- Funk W, Wagnalls H (2003) The new international Webster’s Encyclopedic Dictionary. Columbia: Typhoon International corp. pp: 800-876.

- Garousi, MT, Mehryar AH, Tabatabayi M (2001) Application of the NEO-PI-R Test and analytic evaluation of its characteristics and factorial structure among Iranian university students. Journal of Humanities 11(9):173-198.

- Garrubba M, Harris C, Melder A (2011) Clinical leadership. A literature review to investigate concepts, roles and relationship related to clinical leadership. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Clinical Effectiveness, Southern Health.

- Goldberg LR (1992) The development of markers for the big-five factor structure. Psychological Assessment 4:26-42.

- Goldberg LR (1982) From ace to zombie: Some explorations in the language of personality. In: CD Spielberg, JN Butcher (Eds.), Advances in personality assessment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1: 203-234.

- Health Policy & Economic Research Unit (2012) Doctor’s Perspective on Leadership. British Medical Association, BMA House, Tavistock Square, London.

- Hendrick SS (1988) A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage & The Family 50:93-98.

- Iheonunekwu S, Anyatonwu N, Eze OR (2012) Hospital employees’ interpersonal relationship towards momentary and non-momentary incentives in public enterprises. The State of Healthcare in Nigeria. Onitsha West and Solomon Publishing Co. Ltd. pp:438-471.

- Institute of Medicine (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st National Academies Press.

- Judge TA, Bono JE (2001) Relationship of core self-evaluations traits, self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability with job satisfaction and job performance: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 86(1): 80-92.

- Kouzes JP, Posner B (2002) The leadership challenge (3rd Edn). San Francisco: Jossey Bass, USA.

- Lea A, Watson R, Deary IJ (1998) Caring in nursing: A multivariate analysis. J Adv Nurs 28(3): 662-671.

- Lewis P, Murphy R (2008) Review of the landscape: Leadership and leadership development. National Council for School Leadership, Nottingham.

- Matthews G (1992) Extroversion. In: AP Smith, DM Jones (Eds.) Handbook of Human Performance State and trait 3:95-126.

- Mayo AJ, Nitin N (2005) In their time: The greatest business leaders of the twentieth century Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- McCabe R, Priebe S (2004) The therapeutic relationship in the treatment of severe mental illness: A review of methods and findings. Int J Soc Psychiatry 50(2): 115-128.

- McKinsey Quarterly (2008) A Healthier Healthcare System for the United Kingdom. McKinsey Quaterly Publication p:5-7.

- Mott M (2010) Literature Review: Leadership Frameworks. Mott MacDonald: Bolton.

- Mottram EE (2002) Medical management or clinical leadership? The future of doctors’ involvement in management. Unpublished M. Phil Thesis, University of Aberdeen, UK.

- Mountford J, Webb C (2008) Clinical Leadership: Unlocking High Performance in Healthcare. Health International.

- Mountford J, Webb C (2009) When Clinicians Lead: Health Care Systems that are Serious about Transforming themselves must harness the Energies of their Clinicians as Organizational Leaders, McKinsey & Company.

- Mumford P (1989) Doctors in the Driving Seat. Health Ser J 99(5151): 612-613.

- National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organization (2006) Managing change and role enactment in the professionalized organization. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine pp:1-7.

- National Leadership Council (2012) Clinical Leadership Competency Framework project summary.

- NHS Alliance (2003) Engaging clinicians in the new NHS. NHS Alliance, Retford.

- Nigeria National Health Conference (2009) A communique. Abuja, Nigeria.

- Nwofor AK, Nweke MM (2000) Essentials of management information system. Enugu: Micon-C Production 260.

- Nwosu OC, Ugwoegbu FU, Okeke IE (2013) Self-esteem and perceived levels of motivation as correlates of professional and para-professional Librarians’ task performance in Universities of South-East, Nigeria. International Journal of Humanities & Social Science 2(2): 52-55.

- Opayemi AS, Balogun SK (2011) Extraversion, conscientiousness, goal management, and lecturing profession in Nigeria. African Journals Online IFE Psychologia 19(2): 1117-1421.

- Perks C, Toole MJ, Phouthonsy K (2006) District health programs and health-sector reform: Case study in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84(2):132-138.

- Priebe S (1989) Can patients views of a therapeutic system predict outcome? An empirical study with depressive patients. Fam Process 28(3):349-355.

- Redfern S, Christai S, Norman I (2003) Evaluating change in healthcare practice: Lessons from three studies. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 9(2):239-249.

- Roessler DL (1978) Learning Theory and pro-social behaviour. Journal of Social 28(3):151-163.

- Rosenberg M (1965) Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 148(3671):804.

- Rosenberg M (1979) Conceiving the self. New York: Basic books, Inc.

- Rosenberg M (1989) Society and the adolescent self-image. Middle town, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Rosenberg M, Schooler N, Schoenbach K, Rosenberg P (1995) Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: Different concepts different outcomes. American Sociological Review 60(1):141.

- Royal College of Nursing (2004) Clinical Leadership Tool Kit. London: RCN

- Sheaff R, Rogers A, Pickard S, Marshall M, Campbell S, et al. (2003) A subtle governance: Soft medical leadership in English primary care. Sociol Health Illn 25(5): 408-428.

- Shortell SM, Schmittdiel MC, Wang RL, Gillies RR, Casalino LP, et al. (2005) An empirical assessment of high performing physician organizations: Results from national study. Med Care Res Rev 62(4): 407-434.

- Tenibiaje DJ (2010) Personality and development of crime in Nigeria. Journal of Social Science 2(4).

- Weber V, Joshi MS (2000) Effecting and leading change in health care organizations. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 26(7): 388-399.

- World Health Organization (2007) Everybody business: Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. WHO Document Production Services, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Xirasagar S, Samuels ME, Stoskopf C (2005) Physician leadership styles and effectiveness: An empirical study. Med Care Res Rev 62(6): 720-740.

- Yukl G (2006) Leadership in organizations. Sixth Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...