Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Children in Exploitative Transition: Interface of Child Trafficking, Domestic Workers and Sexual Exploitation, a Case for Uganda Volume 4 - Issue 5

Kasirye Rogers1* and Moses Kinobi2

- 1BA Social work, MA, Human rights, MA Human Rights, Ph.D Candidate, Executive Director, Uganda

- 2BA Social work Senior Social Worker, Centre manager UYDEL, Masooli Rehabilitation Centre, Uganda

Received: March 06, 2021 Published: March 16, 2021

Corresponding author: Kasirye Rogers, BA Social work, MA, Human rights, MA Human Rights, Ph.D Candidate, Executive Director at Uganda

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2021.04.000200

Abstract

Transition in life for young people is taking another trajectory from the known trends and for Domestic Workers (DW) especially girls working as a maids in households less is reported about their transition when they have left domestic work. The descriptive study employed a convenient sample of youth 14-24 years who were withdrawn from transaction sex. A total of 250 girls participated in the survey. The findings revealed that upon return to their homes, the DW economic situation for most girls recruited does not change. The pressure to fend for themselves and family continues and this opens the door to transiting into transactional sex as an alternative for survival. Sexual exploitation of domestic workers comes with a lot of challenges and most times leaves girls worse off as suicide ideation, unresolved mental issues and substance use other high-risk sexual activities. Youth empowerment programs especially vocational skills, mental health and justice awareness interventions are urgently needed to address the economic and social quagmire these girls face at individual and family levels. Future studies need to target and explore the transitional issues of boys as former domestic workers as the information is still scanty.

Keywords: Trafficking; Domestic work; Sexual exploitation

Introduction

Transition in life for young people is taking another trajectory from the known trends. Domestic workers (DW) especially girls working as a (maids) in households are less reported about their transition when they leave domestic work. Whereas many studies capture their experiences and clamor for decent and improved working and regulated conditions [1] there hasn’t been any follow up on their lives after domestic work to help enhance knowledge about their previous experience [2-4]. In Uganda alone, 2.3 million are affected by the child labor. It is common to see children working as maids and doing house help [5]. This type of work is spread both in rural and urban centers. Domestic work is, in fact, one of the most common forms of child employment [6]. The numbers giving estimate this problem of DW is still difficult to come and no single factor appears to explain the SEC phenomenon [7]. Girls in domestic work irrespective of any circumstance are vulnerable. The Modified social stress model [4] remind us that if there a many risk and fewer protective factors children will end up adopting high risk behaviors. Children are sometimes under the control of adults whose first concern is not their wellbeing, but their contribution to the happiness of the employer family. The fact that the vast majority of child domestic workers are girls means that vulnerabilities are compounded by gender considerations especially sexual pressures from men in the household [8,9]. The study was interested in exploring the interface of child domestic work and sexual exploitation in rural and urban Uganda.

Methods

The study was descriptive using a cross-sectional design. It was conducted in May and June 2019 to examine the social demographic characteristics, trafficking patterns of children in both formerly in domestic labor and sexually exploitative situations. The study examined a convenient sample of youth 14-24 years who were under rehabilitation in Uganda Youth Development Link (UYDEL) safe space in the rural setting. Setting and data Collection: The rural and urban UYDEL centers provide vocational training, reproductive health services and psycho-social counseling for disadvantaged children and young people. Study participants were recruited at UYDEL centers in the districts of Mubende, Mityana and Luwero. Over the two weeks of data collection period, a total of 270 young people was reached and only 250 consented to the survey. The study adopted largely a quantitative data collection guide. A structured questionnaire was designed with coded responses. The survey utilized ODK survey software and data was collected via tablets. The research assistants were trained on ethical issues. A pre-test exercise was conducted outside the study UYDEL centers. The study revealed that girls who had ever engaged in domestic work longer shared more, and a few did not want to share their past traumatic experiences. The study received approval by UYDEL IRB.

Results

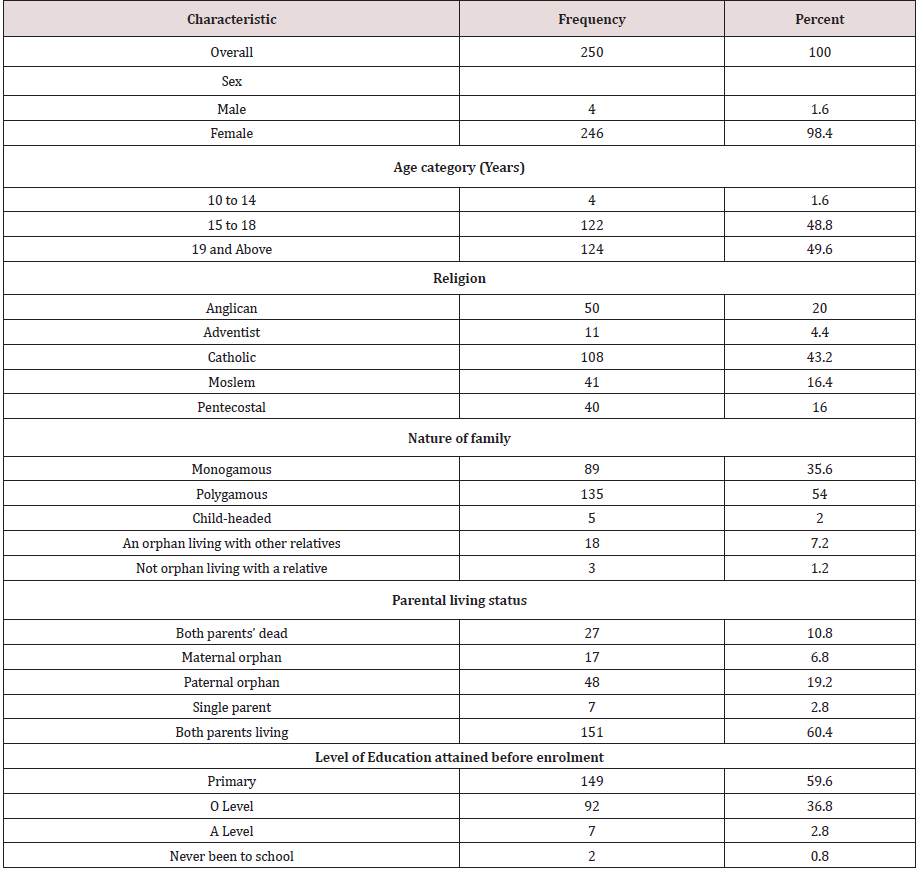

Demographic distribution, family, educational and background of domestic workers. In terms of demographic distribution, majority of the 250 study participants (98.4%) were females and only 4 boys (2%) were males. All had a history of having worked as domestic workers and involved in transactional sex. Majority fell in the age bracket 15-18 years (49%) and those from 19 years above were (50%). The dominant religion were Catholics at (43%) followed Anglicans (20%), Pentecostals and Muslims at (16.4%) each. Interestingly, (60%) of participants had all both parents alive. Only (11%) were total orphans. We noted that slightly over (54%) were from polygamous families and (60%) of participants had dropped out of school at primary level (Table 1). Children from polygamous families are likely to be targeted for domestic work. The presentation of religion by DW was also a true representation of the religious national country picture.

Trafficking and Movements of Children to Domestic Work Destination

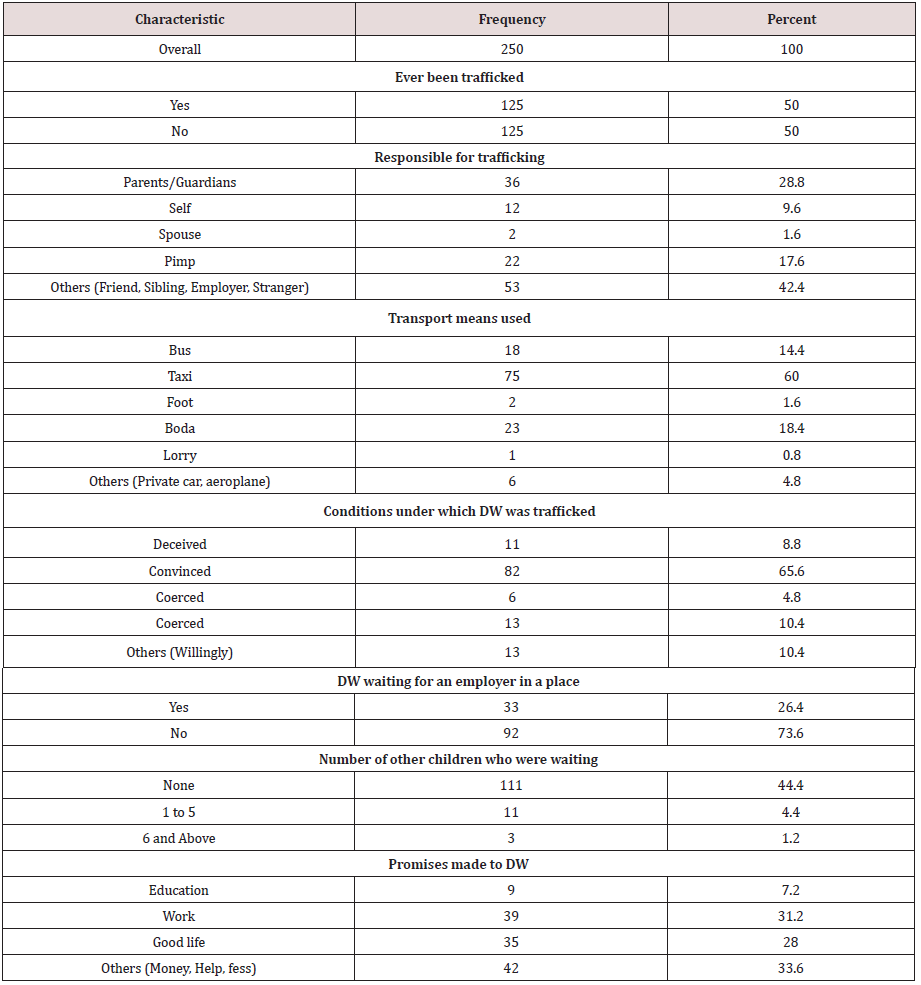

Understanding trafficking is important to establish how girls ended up in DDW. See Table 2:

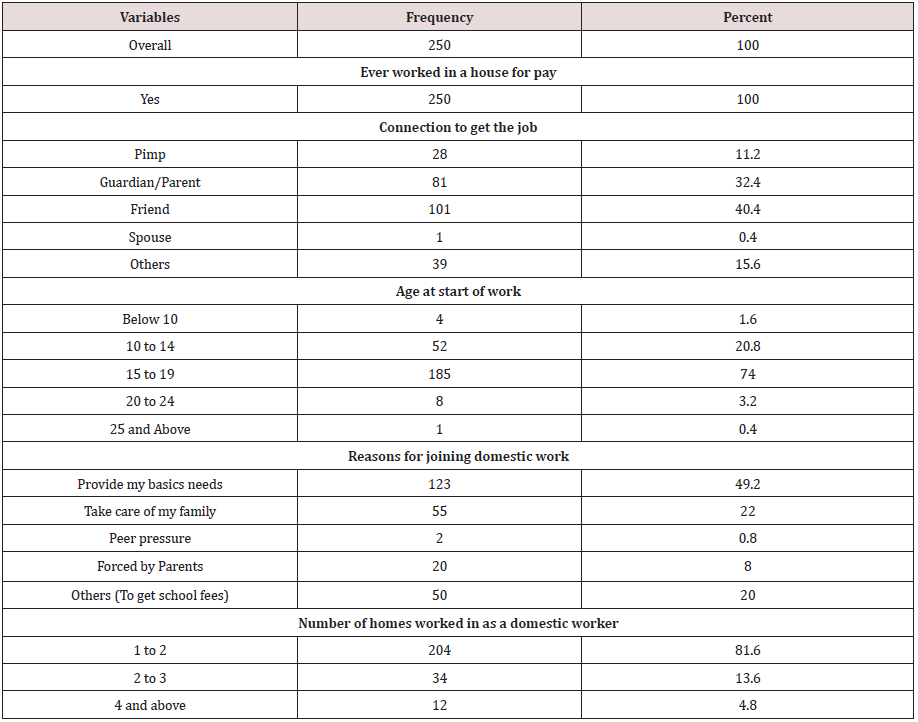

Trafficking and Recruitment Half of the girls (50%) confessed to a movement likened to trafficking. The persons responsible for their trafficking were majorly friends, siblings, employer and stranger (42%) followed by parents/guardians. Friends, parents, and pimps also played a very active role in the recruitment to their destinations. Children mentioned that because places of work were distant most of them used varied transportation and urging DW that they will make more money (71%). A few were coerced. DW on arrival in homes are promised education (31%), good life (28%), and good working conditions (22%). Connection of domestic workers to homes and Age of entry It was revealed that (40%) were linked to homes by friends, another (32%) by guardians or parents, (11%) by pimps and another 16% by unknown others. Friends will normally go back and pick another girl in the same village to a home which is looking for a house girl. The study established that almost (78%) of the participants had one or more of her siblings recruited domestic work for pay. Majority of girls recruited entered DW at the age bracket 14-18 almost (70%); followed by 8-13 years (11.2%). See Table 3 below. It is presumed that girls above 14 years can ably do domestic work chores, submissive and interfere less in other home-related issues.

Reasons, Nature of domestic work and their experiences

The reasons given by participants for joining DW were to provide for my basic needs (49%) and take care of my family (22%). These two factors alone accounted for (71%) for the reasons to go to work. Another (22%) wanted to go work get money and go back to school. A small (8%) alleges that they are forced by parents to go work in homes as DW. DW are paid an average monthly emolument ranging from shillings 5,000 to 35,000{$9 USD} A dollar rate by June 2019 was 3,700 Uganda shilling to 1 $ dollar). Remittance of money home, Duration in homes and Types of homes The findings revealed that (74%) sent money home regularly between shillings 10,000-30,000 [8$ per month] via a mobile phone and only (7%) were saving. The average time spent working as domestic workers ranged between 1-2 years (81%). Another (16%) persists up to 3 years. It was revealed that 33% of participants had their money paid deducted by employers to pay traffickers using their first salary. Employers who engaged DW vary in their capacity in terms of room space, time and chores. Most homes had three bedrooms (65%) and another (28%) had two rooms a sitting and bedroom. Only (7%) had single rooms were sleeping together. It was revealed that (60%) worked in wall fenced homes. The study established (18%) had sexual relationship with their bosses. Of those who had sexual relationship was “consented’ and another was forced. Sexual relationship resulted in terminating their services, beaten and got pregnant.

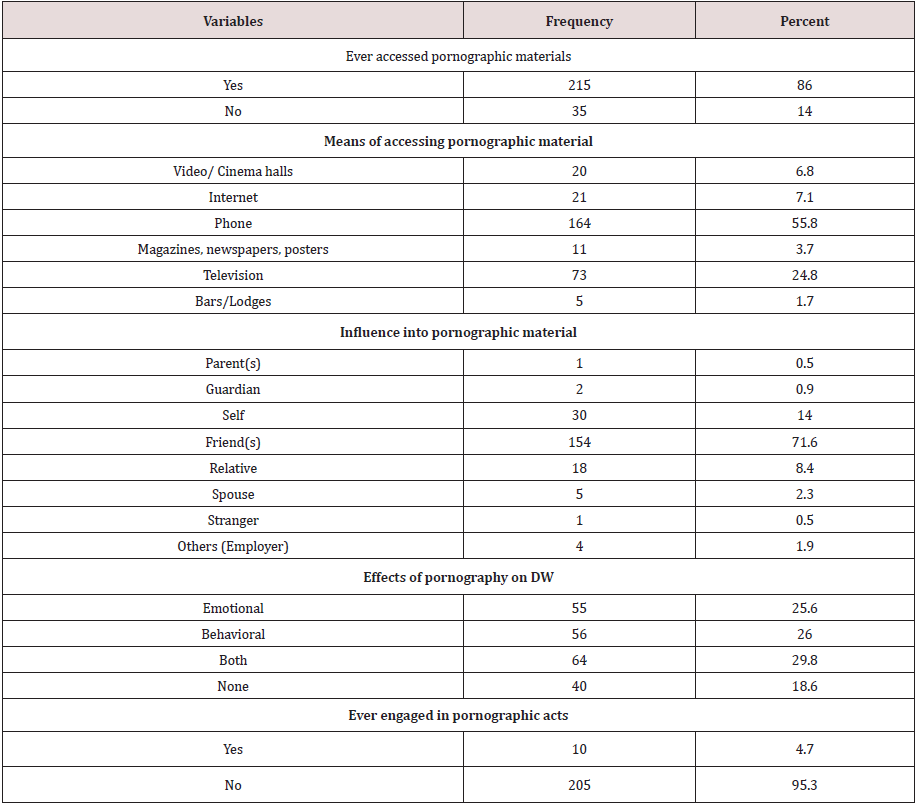

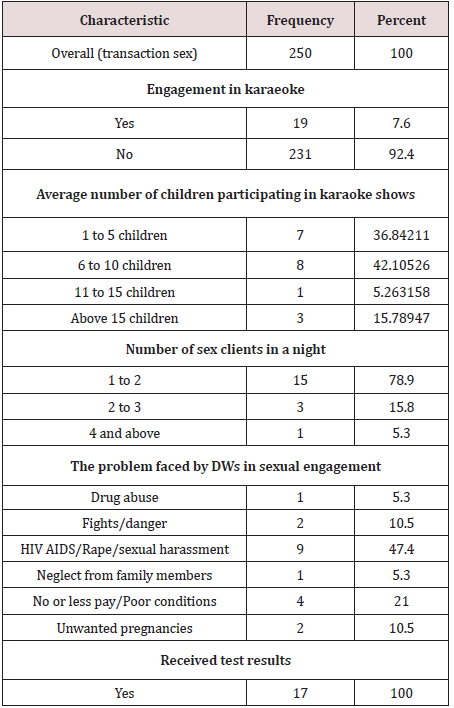

Domestic work and transitioning into sexual exploitation and exposure to pornography Many DWs return home to face the same challenges of poverty and escalated vulnerability and have to fend for themselves. The quickest way is to engage in transactional sex with multiple partners. Most of our interviewees (86%) had viewed sexually explicit images and materials via phones followed by television (25%). Fewer materials are accessed through internet, video magazines, bars and lodges (Tables 4-6). Friends (mostly boyfriends and their clients) facilitate accessing sexually explicit images via online (72%). These are the biggest perpetrators.

Karaoke Groups and Child Sexual Exploitation

Findings showed that a small number had participated in Karaoke activities only (8%), dancing karaoke activities of nude dancing at night in bars; enticed by their friends, sibling and recruited by employers who were mostly men. Most of the training was coached by a peer in the same group. The study participants (58%) mentioned sleeping with clients on their own volition. Others were encouraged by the owner of the group and sleep with 1-2 clients in night and a few sleeps with 3-4 clients. Patrons and fellow peers also prayed on the girls. Participants indicated that there are many other karaoke groups in the area.

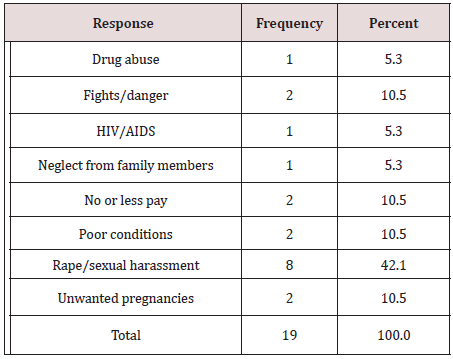

Problems Sexual Exploitation And In Karaoke Related Activities

The most sited problem was rape and sexual harassments (42%), followed by poor working condition (11%), no or less pay per show (11%) fights, unwanted pregnancy (11%) and dangers Use of drugs of abuse (5%). The (74%) had ever been arrested largely for moving late at night and fighting (21percent). Also (7.1%) each had been arrested because stealing a phone, idle and disorderly and engaging in commercial sex. Of the 19 girls, 5 had conceived and had children as a result.

Discussion

The study noted that DW appears to be phenomena that still exist and goes on unbated. Girls are the prime target as early as 14 years, out of school and those experiencing economic challenges in homes. Families with many children get rid of children in anticipation that the girls in DW will partially support the family economically. Other siblings are also surrendered to DW irrespective of their parental status. The traffickers who recruit children are normally given a reward or commission. There was a lot of variation in terms of pay not commensurate to the tasks the girls averaging 18 hours with no break. Children on average will work in 1-2 homes in the first two years and move to another home or return home. Wall fenced homes are reported to be recruiting and receiving more children, followed by homes with two rooms. Families living in a single room also employ child domestic workers. The giving pseudo names to DWs makes reaching them very difficult and inhuman mistreatment goes unnoticed and problems. We deduced that domestic workers face a myriad of problems and this leaves them traumatized. A small number end up in forced sexual relationship with their bosses and thus, end up being forced out of the homes, terminate their pregnancies, quit when mistreatment becomes unbearable and almost to human slavery (Miller, 2005). Suicide ideation and unattended mental health needs were also raised. The DW scenario in their homes agrees with the Modified social stress model indicating that if there are many risks the child’s life the girls are likely to engage in risky behavior. Conversely, the more protective factors that are present for girls to inoculate the stress, the less likely the DW to become involved in (Rhodes, et al 1990). Transactional sex, karaoke and use of substance behaviorwas a normalized behavior and, in the end, made the girls more vulnerable to other risks like pregnancy, violence and sexual abuse.

Implications of the Study

This study reveals that some families that are constrained economically will avail the children to anybody including traffickers hoping for a better life in future. Girls will be targeted as a tool for earning supplementary income in city and rural towns; will not work beyond two years, find another place to work or return home. Since the economic situation and other stressors didn’t change, DW become candidates for sexual exploitation and engage with multiple partners in high-risk sexual activities. Online sexual exploitation amongst DW was also an additional gate way to transactional sex. The option of returning DW girls to school is still possible either in mainstream schools or all impediments which will force girls out of school need to be minimized. There is a need to do more public social investments to address negative cultures like polygamy and children as source of money, family livelihood and more interventions that keep girls in schools, have viable empowerment and alternative incomes generating activities. Future studies need to explore the issues of boys as domestic workers as the information about this is still scanty.

Conflict of Interest

This study has no conflict of interest whatsoever.

References

- The Domestic Workers Convention (2011) (No. 189) reflects this when it defines “domestic workers” in Article 1: (a) the term “domestic work” means work performed in or for a household or households; (b) the term “domestic worker” means any person engaged in domestic work within an employment relationship.

- The Domestic Workers Convention (No. 189) and the accompanying Recommendation (No. 201), both adopted in 2011, offer a historic opportunity to make decent work a reality for domestic workers worldwide.

- Conventions on the Rights of the Child 1989, Optional Protocol and worst forms of child labor.

- Leonard A, Jason, Jean E, Rhodes (1990) A Social Stress Model of Substance Abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol 58(4): 395-340.

- ILO (2013) Domestic workers across the world: global and regional statistics and the extent of legal protection. International Labour Office pp. 140-146.

- Kasirye R (2007) Uganda Youth Development Link Report(UYDEL).

- Mpyangu CM, Awich Ochen A, Olowo Onyango E, Lubaale YAM (2014) Out of School Children Study in Uganda, Stromme Foundation.

- UYDEL (2011) Report on Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children.

- UYDEL (2019) Uganda ECO Report.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...