Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Effect of Obesity, Socio-Economy and Interactions on Mental Health: A Study of Adolescents in Kolkata, India Volume 6 - Issue 1

Fanny Menugea, Estelle Descouta, Sana Arrouba, Céline Lafont Lecuellea, Emeline Gautierb, Manuel Mengolib* and Patrick Pageata*

- aResearch Institute in Semiochemistry and Applied Ethology (IRSEA), Quartier Salignan, 84400 Apt, France

- bClinical Ethology and Animal Welfare Centre (CECBA), IRSEA, Quartier Salignan, 84400 Apt, France

Received:November 15, 2021; Published:November 30, 2021

Corresponding author: Hagar Goldberg, The University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver Campus, 2329 West Mall, Vancouver BC, V6T 1Z4, Canada

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2021.06.000228

Abstract

Guide dogs are a major resource for people with visual impairment. Unfortunately, more than one-third of them are reformed each year because they do not have the required qualities. Their specific training leads them to establish several interspecific attachment bonds, the first one with their puppy raisers, which constitutes an important emotional base for their future cognitive-emotional development and mental stability. Eight guide dogs aged between 1 and 2 years in the training period and their puppy raisers were involved. This is a preliminary study that aimed to investigate attachment behaviours in guide dogs towards their puppy raisers using the Strange Situation Test (SST). The second goal was to assess the suitability of using psychometric scales measuring the emotional state of the animals in this shared-custody context. Two psychometric scales that reflect dogs’ impulsivity and sensitivity levels were applied through questionnaires-the Dog Impulsivity Assessment Scale (DIAS) and the Positive and Negative Assessment Scale (PANAS)-completed by the puppy raisers and principal trainers. The SST revealed a preference among the dogs for their puppy raisers over a stranger, as evidenced by expressing more secure base effect behaviour when the puppy raiser was present (Tukey-Kr; DF=13.9; t=3.05; p=0.02) and greater proximity seeking behaviour towards the puppy raiser than towards the stranger (Student’s t-test; DF=1; t=2.66; p=0.03). The test also highlighted a strong difficulty in remaining alone, as demonstrated by a longer duration of door proximity behaviour when alone (Tukey-Kr; DF=7; t=5.15; p<0.001). Notably, the results of the questionnaire score analysis revealed a discordance between the perception of educators and puppy raisers, giving uncorrelated scores. This study will be repeated once the dogs have been adopted by visually impaired children to assess the continuity of the attachment bond developed with the foster family over time and determine whether this bond influences the success of the dogs and their ability to create a new bond in the long term.

Keywords: Ainsworth Strange Situation Test; Attachment; Emotional state; Foster family; Human dog relationship

Introduction

Guide dogs accompany people with visual impairments to

increase their independence by providing them assistance in their

daily tasks [1]. The relationship is based on mutual trust, which is

essential for the proper functioning of the dyad [2]. Indeed, the dog

must be able to deal with all sorts of unforeseen circumstances that

might be encountered in the course of its work. Not reacting when

faced with a sudden event, organizing the environment, and showing

the way when encountering an obstacle are all indispensable skills

that help ensure the safety of the person and the fluidity of his/

her movement [3]. Emotional balance and the capacity to cope with

emotional distress are therefore the most desired characteristics in

guide dogs [4]. These characteristics could play a fundamental role

in both the acquisition of relevant skills and in the dog’s ability to put

these skills into practice every day with the person it accompanies.

Unfortunately, a large proportion of dogs are excluded from the

guide dog programme [5-7]. In 2016, the percentage of reformed

or reoriented dogs was estimated at approximately 40% in France

[8], of which 60% occurred for behavioural reasons [9]. Dogs are

usually trained by a federated association, foundation or training

programme. Early detection of problems or difficulties is therefore

desirable to avoid as much financial and time loss as possible due

to the high cost of each animal for diet, health care and training,

which usually amounts to between 20,000 and 25,000 euros per

dog in France [10].

As a result of training, guide dogs establish different emotional

bonds with different people during the first two years of life: the dog’s mother and siblings initially, then the foster family, the

educator, and finally the visually impaired person the dog will

accompany. Foster families keep dogs from the weaning stage and

teach them basic rules in terms of education. They are therefore

considered very important in the breeding of future guide dogs

[11]. Attachment, as developed, is described as the product of

behaviours aimed at seeking and maintaining proximity to a

specific person. This is an important concept defended by several

authors, including [12-15], who claim that the theory is valid for

all mammals. According a secure base effect is the main factor

indicating the presence of an attachment bond between two

individuals. Accordingly, they constructed the strange situation

test (SST - fully described by the authors, 1970) to measure the

relationship between a child approximately one year old and

his or her significant person, most often the mother. Since then,

several researchers have shown that attachment can also exist

interspecifically between a dog and its handler, thanks to a revised

version of this test, the SST-R [16-20]. The presence of this bond was

confirmed by the work and who stipulated that people can act as a

secure base for their dogs. This paper is a preliminary study of the

largest research area. The goal is to understand the bond developed

by the future guide dogs towards their puppy raisers and to assess

the appropriateness of using scales measuring the emotional state

of the animals through its levels of sensitivity and impulsivity in

this particular context, in which several people share phases of dog

development. The study was conducted in collaboration with the

Frederic Gaillanne Foundation (L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, France), which

is the first school in Europe to train guide dogs only for children

with visual impairment and assistance dogs for children with

developmental disabilities.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Eight dogs, including 5 females and 3 males St. Pierre dogs from the Frederic Gaillanne Foundation participated in the study with their puppy raiser. They were all neutered and had a mean age of 24 months (± 6 months). To be included in this study, they had to live with their foster family for at least 3 months and not have experienced any major change in their routine before the test. They all started their guide dog training 7 months ago. They are at the foundation from Monday to Friday, then they go back to their host families on weekends.

Experimental design

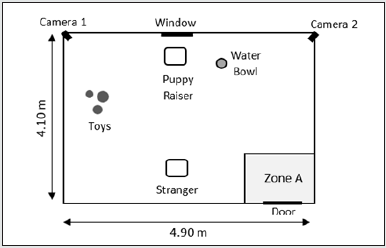

The experimental environment was as close as possible to the standards used in the SST-R [21,22]. The room (4.9 m × 4.1 m), which was located at the Clinical Ethology and Animal Welfare Centre (CECBA) of the Research Institute in Semiochemistry and Applied Ethology (IRSEA), was unfamiliar to the dogs. The room was equipped with 2 chairs, 3 toys, 1 water bowl and 2 cameras (Figure 1). All tests were performed in the late morning between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., and only 1 test was performed per day to avoid any possible olfactory influence.

Figure 1: The experimental room was equipped with two chairs, three dog toys, a water bowl and two video cameras. Zone A (1.40 m x 1.30 m) = Door Proximity Area.

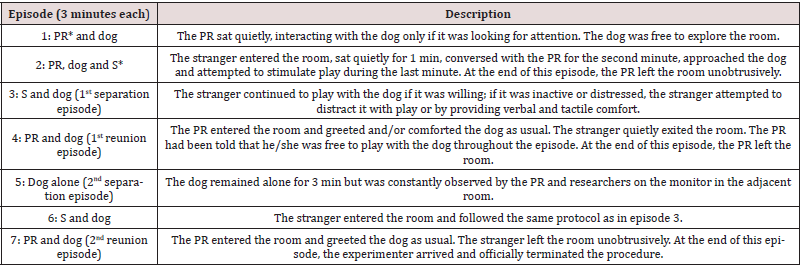

Procedure

The puppy raiser participating in the experiment had previously received and completed two questionnaires-the Positive and Negative Assessment Scale for dogs (PANAS) [23] and the Dog Impulsivity Assessment Scale (DIAS) [24]-via Google Forms; these scales measure the levels of sensitivity and impulsivity of dogs, respectively. The PANAS consists of 21 items, and the DIAS consists of 18 items. Both questionnaires use a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. A “don’t know/not applicable” option was also possible. The lead educator for each dog was also asked to complete the PANAS and DIAS. The experiment was based on the modified version of the Ainsworth SST adapted to dogs [15,17] and was video recorded. The experimental phase was divided into the episodes described in Table 1. The same woman played the role of the stranger in all scenarios as described in the literature [7,12,16]. All participants signed an authorization to acquire, reproduce and broadcast images.

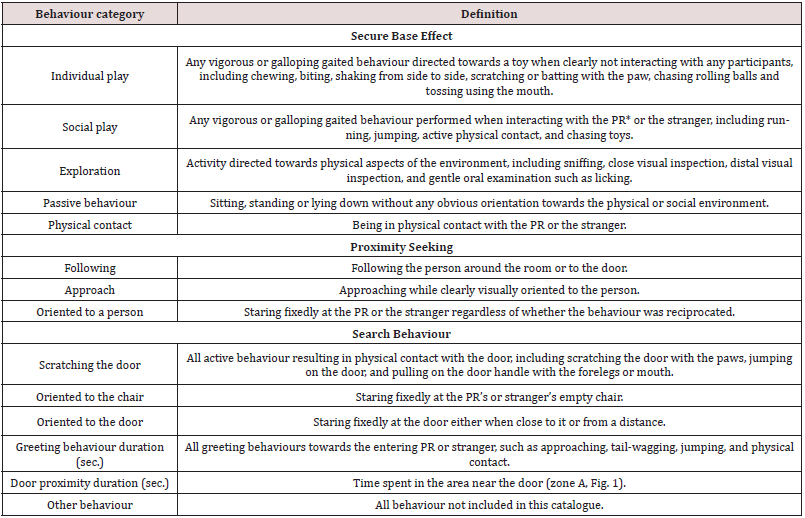

Data collection

All tests were filmed and analysed twice by the same person at 6-month intervals to evaluate intraobserver reliability. Behavioural Observation Research Interactive Software (BORIS) [10] was used with the 5-second interval scan sampling method for the 7 episodes. Based on previous studies [4,12,13], the behaviours described in Table 2 were noted and organized into categories. These behaviours were mutually exclusive, except for “physical contact” and “greeting behaviour”, which could be associated with each other. The duration of “greeting behaviour” and “door proximity” was also collected. The sensitivity (PANAS) and impulsivity (DIAS) questionnaires were scored according to the method described by the authors [20,24], yielding scores between 0 and 1. The two scales comprise different factors and the following scores:

1. The DIAS includes 4 scores: “behavioural regulation”,

“aggression/response to novelty”, “responsiveness” and

“overall score”.

2. The PANAS includes 5 scores: “negative activation” and

“positive activation”, itself composed of “energy and interest”,

“persistence” and “excitement” scores.

Statistical analysis

The analyses were carried out using SAS 9.4 software Copyright (c) 2002-2012 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. The significance threshold was classically fixed at 5%.

Evaluation of attachment

Intraobserver reliability between the 2 observations separated by a 6-month interval was assessed for each parameter (“secure base effect”, “comfort seeking”, “proximity seeking”, “search behaviour”, “greeting behaviour” and “door proximity”). Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated if the hypothesis of normality of the parameters being compared was verified; otherwise, Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated. The behaviours “physical contact”, “proximity seeking”, and “greeting behaviour” were analysed using a 2 x 2 comparison between the puppy raiser and the stranger. For this purpose, after checking the normality conditions, Student’s t-test for matched samples was carried out using the t-test procedure. The behaviours “secure base effect” and “search behaviour” were compared between episodes 2 and 4 and episodes 3 and 6, respectively. The “door proximity” behaviour was analysed under 3 conditions: when the dog was alone (episode 5), when the dog was in the presence of the puppy raiser (the average of episodes 2, 4, and 7), and when the dog was in the presence of only the stranger (the average of episodes 3 and 6). To do this, the assumption of normality was tested using the residual diagnostics plots and the UNIVARIATE procedure. Comparisons between conditions were performed with a general linear model (GLM) using the MIXED procedure to consider repeated measurements. The best variance-covariance matrix was selected by minimizing the AICC and BIC of the model. When a significant difference was observed, multiple comparisons were made using the Tukey- Kramer test using the LSMEANS statement.

Evaluation of psychometric scales

Regarding the DIAS and PANAS questionnaires, 2 x 2 correlations were made between the responses of the puppy raisers and educators for the overall scores and each of the factors. For this purpose, when normality was verified using the UNIVARIATE procedure on SAS software, the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated using the CORR procedure. Normality was not verified for the “aggression/response to novelty” factors or the overall DIAS score, and the Spearman correlation coefficient using the CORR procedure was preferred. According to Martin and Bateson (2007), r = 0.4-0.7 indicates a moderate correlation (substantial relationship), r = 0.7-0.9 indicates a high correlation (marked relationship) and r = 0.9-1.0 indicates a very high correlation (very dependable relationship). Finally, the association was evaluated by computing the square of the correlation coefficient.

Results

Strange Situation Test

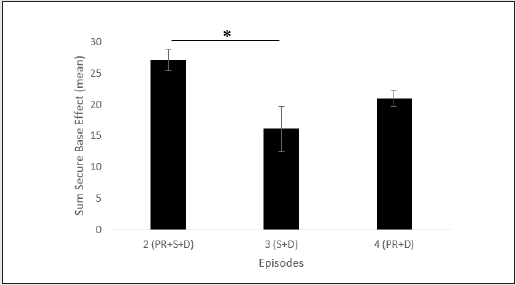

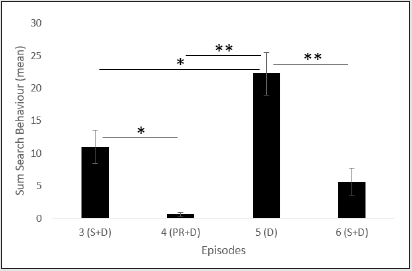

The statistical analysis of intraobserver reliability revealed a strong association (≥ 80%) between the observations for each parameter, with a minimum correlation of 0.89 (significance test; p<0.001). The results obtained for the “secure base effect” highlighted significant differences between episodes (GLMM; DF=2; F=4.66; p=0.03), with behaviours expressed more often when the puppy raiser was present with the stranger than when the dog was alone with the stranger (Tukey-Kr; DF=13.9; t=3.05; p=0.02) (Figure 2). “Proximity seeking” behaviours were also more common in the presence of the puppy raiser than in the presence of the stranger (Student’s t-test; DF=1; t=2.66; p=0.03). To support these results, significant differences were found between episodes for “search behaviour” (GLMM; DF=3; F=11.00; p=0.01) and “door proximity” (GLMM; DF=2; F=11.98; p<0.001). These behaviours were significantly less common in the presence of the puppy raiser and when the dog was in the presence of the stranger than when the dog was alone see Figure 3. Contrary to findings reported in the literature [15], data obtained for “greeting behaviour” were not significantly different across episodes (Student’s t-test; DF=1; t=0.61; p=0.56), and a tendency was found for “physical contact” towards the stranger (Student’s t-test; DF=1; t=-2.14; p=0.07).

Figure 2: Episode effect on secure base effect. The mean ± standard error. S = Stranger; PR = Puppy Raiser; D = Dog. *p < 0.05.

Figure 3: Episode effect on search behaviour. The mean ± standard error. S = Stranger; PR = Puppy Raiser; D = dog. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

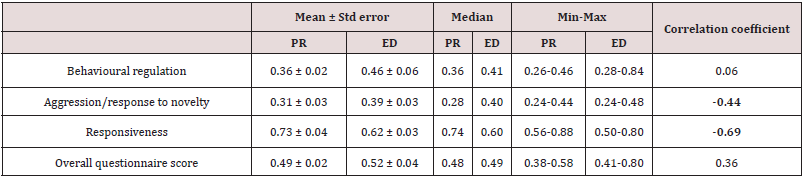

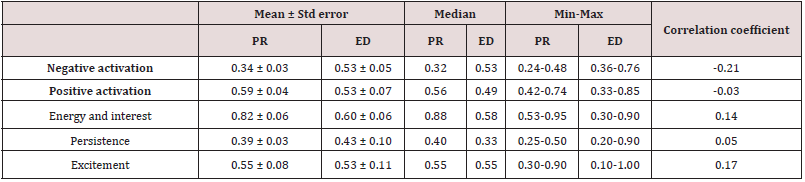

Psychometric scales

On the psychometric scales, no significant positive correlation was found between the responses of puppy raisers and educators. However, moderate negative correlations were detected for the reactivity score (r = -0.69; p = 0.06) and aggressiveness/response to novelty (Tables 3,4).

Table 3: Table of descriptive data and correlations between the results of the scores on the DIAS completed by the puppy raisers (PR) and the educators (ED).

Table 4: Table of descriptive data and correlations between the results of the scores on the PANAS completed by the puppy raisers (PR) and the educators (ED).

Discussion and Conclusion

The objectives of this preliminary study were to investigate

attachment behaviours in guide dogs and determine whether

the impulsivity and sensitivity scales could be reliable indicators

of the emotional state of these animals in this context of sharedcustody

dogs. The attachment relationships between dogs and

their puppy raisers were assessed using the modified version of

the Ainsworth SST-R. In this study, no inappropriate or pathological

attachment was observed in the dogs, who expressed a preference

for their puppy raisers. Regarding the psychometric scales, both

the educators and the foster family were asked to complete the

questionnaires to compare scores, but unexpectedly, no correlation

was found, asking about the most reliable person to answer these

questionnaires.

In the results obtained for the attachment test, comparisons

of “secure base effect” behaviours according to episode revealed

a higher occurrence of these behaviours in episode 2 (stranger

and puppy raiser) than in episode 3 (stranger). This indicates that

in the presence of an unknown person, puppy raisers facilitate

their puppies’ coping strategies, defined in psychology as a set

of cognitive and behavioural efforts that individuals deploy in

response to environmental variations they assess to be threatening.

The presence of their attachment figure allows dogs to focus on

the environment and interact with it more serenely. No significant

differences in the “secure base effect” were found between episodes

in which the dog was alone with the stranger (episode 3) and when

it was alone with its puppy raiser (episode 4), unlike the results

found and for both pet and working dogs (search and rescue

dogs). In the present study, the presence of a stranger without

established attachment with the dog did not prevent the dog from

interacting confidently with the environment. Due to their training

background, these dogs are subject to strong socialization and

to high human contact from an early age and are not alone more

than 4 hours per day. Subjects in the study [2] had a less disturbed

routine, spending a good part of their days with only their owner(s)

or alone at home, which could explain this discrepancy in results.

Episodes 2 (stranger and puppy raiser) and 4 (puppy raiser) were

also similar, as expected. Indeed, as long as the puppy raiser was

present, the company of a stranger did not have a significant impact

on the behaviours, indicating a secure base effect.

Despite a similar secure base effect in episodes 3 and 4, the dogs

exhibited more searching behaviours, including “door orientation”,

when the puppy raiser was not in the room (episode 3). And he has

shown that with secure attachment, searching behaviours are more

common in the absence of the owner. In this study, a preference for

the puppy raiser should be noted, and the preference may result

in a functional attachment. These behaviours also occurred more

often when the subjects were alone in the room than when in the

presence of only the stranger. This observation may show that a

person, even if unknown, is able to reduce the expression of certain

behaviours expected during a separation from the owner. Some

difficulty in remaining alone may be expected if attachment is too

strong, as mentioned above. The conclusions are similar for time

spent near the door; human presence was preferred over being

alone, resulting in a large amount of time spent in the area near the

door when the dog was alone.

In accordance with what is found in the literature [7,14] ,

more “proximity seeking” behaviour was exhibited towards the

puppy raiser than towards the stranger during the test. These

behaviours are representative of a visual search, looking for

someone. This could represent the previously mentioned coping

strategy, facilitating the return to exploration or other interactions

with the environment (a secure base effect) after searching for

the attachment figure. Physical contact, which is associated with

an attachment bond [15,22], was not significantly higher for the

puppy raiser and even showed a reverse trend during the test. In

the absence of their puppy raiser, the dogs tended to interact with

the unknown person through physical contact while performing

searching behaviours (orientation towards the door, proximity

to the door) simultaneously. The dogs moved between the door

and the person, so physical contact could be interpreted here as

a sign of seeking comfort and therefore be emotionally palliative,

as previously discussed and is on one of their study. Finally, the

times spent greeting the puppy raiser and the stranger when they

entered the room were also comparable, contrary to expectations

and the results, which showed that dogs generally spend more time

greeting and in physical contact with their owners. The training

received by these dogs and breed selection (St. Pierre) aim to

foster close relationships between these animals and humans and

to encourage the dogs to spontaneously seek contact, even with

unknown people, which could justify these results.

One of the most important steps in the breeding of a guide

dog is the period during which it lives with its foster family [15],

which is why this study focused on the relationship that dogs can

establish with their primary raisers. The foster family represents

a particular situation in which the puppy raiser is not the real

owner of the animal. Foster families, unlike dogs, are warned of

the temporary nature of the relationship and tend to develop an

avoidant type of attachment as a form of resistance in contrast to

the animal, which develops attachment as any other puppy would

with its new family. Accordingly, the first bonds of attachment that

the animal establishes with humans-the puppy raiser in this casemay

impact the mental balance of the dog and the implementation

of coping strategies adapted to its work as a guide dog, allowing it

to effectively manage daily challenges and respond adequately to

unforeseen circumstances. Thus, the foster family is considered a

very important element in the breeding of future guide dogs [12]. In

this pilot study, the attachment between the dogs and their puppy

raiser seemed balanced and functional, as the dogs recognized their

puppy raiser as the person caring for them (feeding them, playing,

etc.). The dogs also seemed to manage the strange episodes in the

presence of an unknown person.

These dogs, generally benefiting from good socialization, would

have greater interest in foreign persons than do pets, which agrees

with the results of previous studies [5,16]. Desire for human contact

makes it easier for these dogs to compensate and bridge the gap with another human when their puppy raiser is absent. They frequently

experience separations from their puppy raiser (training period

with the educator at school) and interact with different people. It

is important to note that these changing environments may raise

questions about their well-being and the consequences it may have

on the quality of their work. Several works [18,17] have shown that

good welfare is linked to abilities and training performance in guide

dogs. For this reason, it would be interesting to assess, in a future

study, the impact of these multiple separations on the welfare of the

dogs and thus on their ability to perform as guide dogs.

Puppy raisers and educators also completed psychometric

scales to assess levels of impulsivity (DIAS) and sensibility (PANAS).

A good emotional balance is fundamental to obtaining a good guide

dog [11]. The aim here was therefore to determine whether these

scales could be relevant tools and good indicators of the emotional

state and so of the success of these dogs. No statistical positive

correlation was found between the scores given by the educators

and the puppy raisers in this context. In particular, “reactivity” and

“aggressiveness/response to novelty” showed a moderate negative

correlation. The reactivity score was higher in the answers of

foster families answer, and the aggressiveness score was in those

of the trainer. Several factors could explain these results. Indeed,

even if the dogs live with the foster families, dog trainers are

more experienced in evaluating dogs and could tend to be more

demanding towards them because certain behavioural traits must

be exhibited before a deadline in order for a dog to receive its

certification. Another reason could be that the dogs act differently

depending on their environment. They could learn that the foster

family’s home is a more permissive environment than the guide

dog school. The limits given by the educator may be more specific,

clearer and more comprehensible than those given by foster

families. Finally, dogs are not exposed to the same stimulations in

the same way. In fact, dog trainers are used to anticipating dogs’

reactions to external stimulation, which may reduce the reactivity

of the dog, but puppy raisers have less experience in this domain.

In this context, it is difficult to use these psychometric scales

on guide dogs in an ongoing training program. It would be

interesting to use a larger sample to determine whether there is

a relationship between the results of these scales (from puppy

raisers or dog trainers) and a dog’s success, and whether the

type of relationship established with the puppy raiser enables a

lasting and complementary guide dog/child dyad. These results

could be useful for identifying dogs with undesirable behaviours

as soon as possible, to exclude them from the training program

to avoid financial losses, or to focus the education on problematic

behaviours.

Funding

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Frederic Gaillanne Foundation, the foster families and the dogs for their collaboration and participation, Cécile Bienboire-Frosini and Míriam Marcet-Rius for their review of the manuscript and American Journal Experts (AJE) for the English editing.

Ethics Approval Statement:

This project was approved by the Research Institute in Semiochemistry and Applied Ethology (IRSEA) Ethics Committee (approval number CE_2020_01_ADOB01).

References

- Ainsworth M, Bell S (1970) Attachment, exploration, and separation: illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Dev 41(4): 49-67.

- Batt L, Batt M, Baguley J, McGreevy P (2008) Factors associated with success in guide dog training. Journal of Veterinary Behavior Clin Appl Res 3(4): 143-151.

- Bowlby J (1978) Attachement et perte. puf Paris.

- Dupont Gauzins A (2002) Réforme des chiens d’assistance pour handicapés moteurs au cours de leur période de formation. Med Vet Nantes.

- Fallani G, Prato Previde E, Valsecchi P (2007) Behavioral and physiological responses of guide dogs to a situation of emotional distress. Physiology & Behavior 90(4): 648-655.

- Friard O, Gamba M (2016) BORIS: a free, versatile open-source event-logging software for video/audio coding and live observations. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7(11): 1325-1330.

- Gazzano A, Mariti C, Sighieri C, Ducci M, Ciceroni C, et al. (2008) Survey of undesirable behaviors displayed by potential guide dogs with puppy walkers. Journal of Veterinary Behavior Clin Appl Res 3(3): 104-113.

- Goddard M E, Beilharz RG (1982) Genetic and environmental factors affecting the suitability of dogs as guide dogs for the blind. Theor Appl Genet 62(2): 97-102.

- Harlow H (1958) The nature of love. Am Psychol 13: 573-685.

- Koda N (2001) Development of play behavior between potential guide dogs for the blind and human raisers. Behav Processes 53(1-2): 41-46.

- Koda N, Kubo M, Ishigami T (2011) Assessment of dog guides by users in Japan and suggestions for improvement. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 105(10): 591-600.

- Mariti C, Ricci E, Carlone B, Moore JL, Sighieri C,et al. (2013) Dog attachment to man: A comparison between pet and working dogs. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 8(3): 135-145.

- Mengoli M, Mendonça T, Lee Oliva J, Bienboire Frosini C, Chabaud C, et al. (2017) Do assistance dogs work overload? Canine blood prolactin as a clinical parameter to detect chronic stress-related response, in: Proceedings of the 11th International Veterinary Behaviour Meeting.

- Naderi S, Miklósi Á, Dóka A, Csanyi V (2001) Co-operative interactions between blind persons and their dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 74(1): 59-80.

- Oliva JL, Mengoli M, Mendonça T, Cozzi A, Pageat P, et al. (2019) Working Smarter not Harder: Oxytocin Increases Domestic Dogs’ (Canis familiaris) Accuracy, but not Attempts, on an Object Choice Task. Front Psychol 10: 2141.

- Palestrini C, Previde EP, Spiezio C, Verga M (2005) Heart rate and behavioural responses of dogs in the Ainsworth’s Strange Situation: A pilot study. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 94(1-2): 75-88.

- Palmer R, Custance D (2008) A counterbalanced version of Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Procedure reveals secure-base effects in dog-human relationships. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 109(2-4): 306-319.

- Prato Previde E, Custance D M, Spiezio C, Sabatini F (2003) Is the dog-human relationship an attachment bond? An observational study using Ainsworth’s strange situation. Behaviour 140: 225-254.

- Rooney N, Gaines S, Hiby E (2009) A practitioner’s guide to working dog welfare. Journal of Veterinary Behavior Clin Appl Res 4(3): 127-134.

- Sheppard G, Mills DS (2002) The Development of a Psychometric Scale for the Evaluation of the Emotional Predispositions of Pet Dogs. Int J Comp Psychol 15: 201-222.

- Topal J, Miklosi A, Csanyi V, Doka A (1998) Attachment Behavior in Dogs (Canis familiaris): A new application of Ainsworth’s (1969) Strange Situation Test. J Comp Psychol 112: 219-229.

- Valsecchi P, Previde EP, Accorsi PA, Fallani G (2010) Development of the attachment bond in guide dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 123(1-2): 43-50.

- Vincent IC, Leahy RA (1997) Real-time non-invasive measurement of heart rate in working dogs: A technique with potential applications in the objective assessment of welfare problems. The Veterinary Journal 153(2): 179-183.

- Wright HF, Mills DS, Pollux PM (2011) Development and validation of a psychometric tool for assessing impulsivity in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). Int J Comp Psychol 24: 210-225.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...