Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Review ArticleOpen Access

Anxiety: A Subconscious Workplace Mental Health Challenge: Developments in Subconscious Solutions Volume 6 - Issue 4

Petrina Coventry*

- Adelaide University and South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Australia

Received: June 19, 2022; Published: August 02, 2022

Corresponding author: Petrina Coventry, Adelaide University and South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Australia

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2022.06.000243

Abstract

By comparing this diagram of hydration temperature-study time A, B, C, and D is observed at a depth of 5 cm, in the sample without fibers, the hydration temperature is much higher than in the samples with fibers, also by comparing the sample B (fibers 0.5%) and sample C (1% fiber) was observed that with an increase of 0.5% in the number of fibers from sample B compared to sample C, it was observed that the heat of hydration decreased by 12.3% at a depth of 5 cm, also by comparing sample B And D was observed with an increase of 0.5% in the number of fibers witnessed a decrease in hydration temperature of 14.5% at a depth of 5 cm (Figure 11).

Keywords: Anxiety; Mental Health; Hypnotherapy; Productivity; Subconscious

Introduction

Anxiety has risen during the Covid10 pandemic [1]. When people enter the workplace, they do not leave their emotions behind, and emotions influence how people work. Anxiety is an emotion that underpins much behaviour in organisations and eemployees experiencing anxiety double the risk of poor work performance and productivity [2,3]. It is highly personalized, varying widely by individual and occurring as the result of a stimulus that triggers automatic responses, normally fear, panic, and worry. When fear, panic or worry is experienced, subconscious structures can trigger repeated automatic responses until neural patterns or behaviours are subconsciously modified [4]. Subconscious solutions exist, but they may not be known about or well understood. Hypnotherapy is a solution that has been clinically trailed to deal with anxiety but has not yet been widely adopted in workplaces where anxiety has a productivity impact [5]. Understanding what perceptions and barriers to this practice exist with workplace mental health providers was important as an aim for this research.

Anxiety is a constant state – at work and outside work

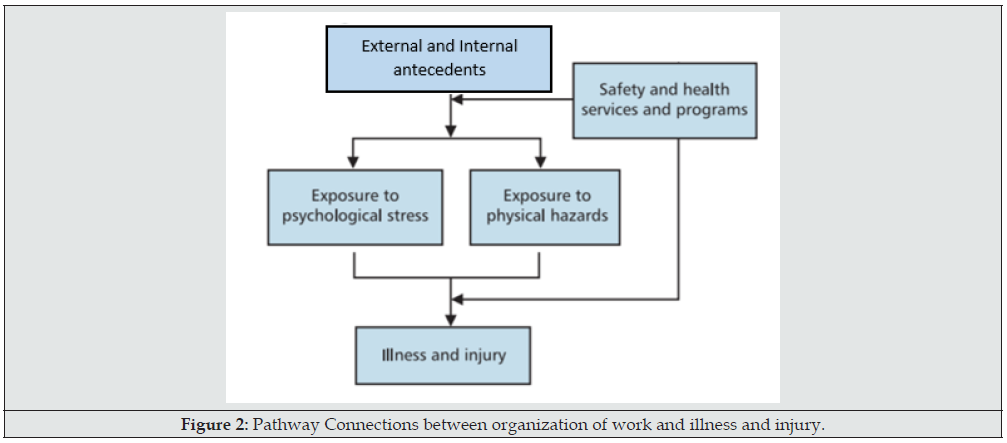

Antecedents that drive anxiety can exist within the workplace and be external to the workplace therefore a combination of workplace and wholistic lifestyle solutions are ideal. Health and safety programs are increasingly important in dealing with the issue and although historically many health and safety programs were focussed on physical safety, increasingly take into account mental health and wellbeing in the service offering. Those programs require a psychological focus to ensure that injury or illness which can impact workplace productivity can be mitigated as seen in Figures 1 & 2.

Source: workplace wellbeing pathways through occupational health and safety

Without effective management anxiety can seriously impact employees’ productivity, and health, and whilst there is increasing awareness around the need for mental health programs, there remains a disconnect between employers’ intentions against the measurement of what actually works. This means that employees often do not get the help they need to maintain a fulfilling and productive working life, and some line managers are frustrated by the lack of support they need to help their employees.

Performance and productivity impact

A high performing organization is a common goal of organizations and scholars have empirically established a relationship between work systems and a variety of organizational outcomes including performance, productivity, and turnover [6]. There are some recently developed multidimensional models of the anxiety and performance relationship applied to sport which make predictions that, under certain conditions, increases in cognitive anxiety can have beneficial effects on performance [7]. Theorists [8] argue that anxiety impairs performance on tasks with high attentional or short-term memory demands and continues to be associated with poor job productivity as well as short and long-term work disability [9]. Employees experiencing anxiety suffer more than double the risk of poor work performance [3,10]. Individual productivity can be affected by characteristics of decreased patience, inability to multitask, difficulty in making decisions, lack of concentration, a slowdown in task delivery and overall employee engagement level [11]. This can impact organisational performance in a number of ways including organisational productivity 56%; relationships with co-employees and peers 51%; quality of work 50%; and relationships with superiors 43% [12].

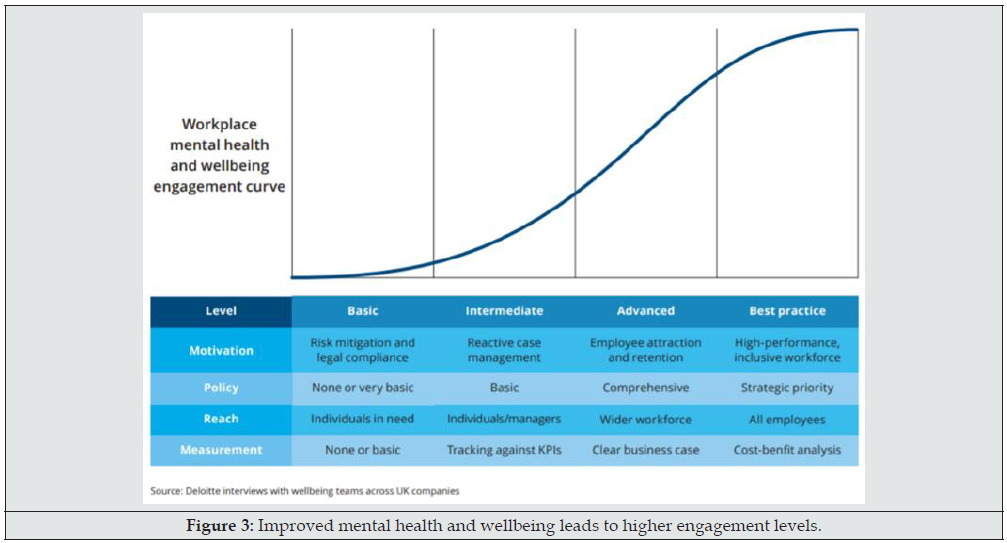

Correlations between mental health and engagement have been mapped as a measurement of workplace productivity as seen in Figure 3. We need a workforce that is energised, engaged, committed and focused on delivering results, however the impact of the covid 19 pandemic has escalated the issue and outpaced our understanding of their implications for work life quality and health on the job.

Mismatched Solutions

Process reengineering, organizational restructuring, and flexible staffing are prime examples of practices that are increasingly prevalent and increased during the pandemic, but there remains only a small body of research with regard to that looks at effects around individual-level intervention strategies, such as anxiety management and mental health promotion during this time [13]. Improving research around the connection between work performance and mental health requires better understanding of subconscious and tacit knowledge connecting anxiety and performance [14], and although there has been an increase in general health and wellbeing program offerings in workplaces there remains only early exploration into programs that deal with subconscious issues. Anxiety is subconscious in nature

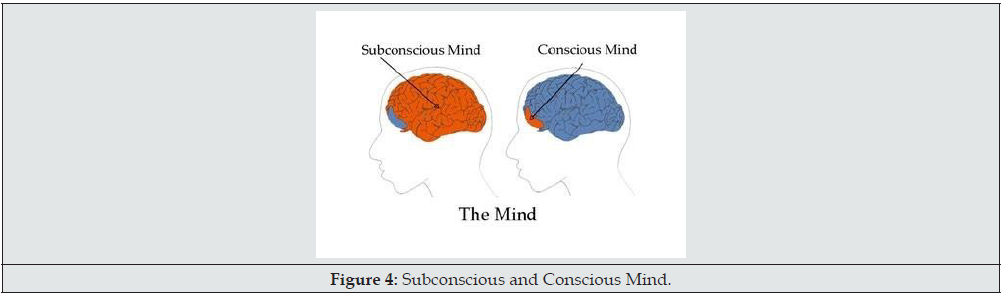

The brain operates at both a conscious and subconscious level. Both levels are critical to the way we process information, and function in concert with the other. The conscious mind uses a small percentage of our brain power, around 10%, the remaining 90% of the processing power is dedicated to our subconscious mind [2]. The subconscious can process 500,000 times more information that your conscious mind, working at a meta level and plays a more than significant role in determining a person’s thinking, emotion, reaction and ability to remain resilient and protected psychologically [15] (Figure 4).

Source: (Hartman & Zimberoff, 2004) [16]

The conscious mind works on the simple, day-to-day tasks controlling willpower, short term memory, logical thinking and critical thinking and, while the subconscious (or unconscious) brain controls, beliefs, emotions, habits, values, protective Reactions, imagination, intuition and long-term memory [17]. Both subconscious rapid defensive responses and conscious defensive responses feature in the clinical picture of anxiety. The subconscious is constantly vigilant and during times of anxiety can override the conscious mind (sometimes referred to as executive function in work settings). If the subconscious mind has coding or incorrect coding based on past experiences which may not match the situation the behaviours may not be appropriate. These incorrect codes can lead to situations that have been identified as the wounded self which is akin to Jung’s complex [18], Beck’s negative self-schemas [19], Fonagy’s foreclosure of mentalisation [20], and the wounded-self ego state from ego state therapy [21]. The emotional state of anxiety can all lead to significant errors in judgement, action and impact for individuals and organisations. If anxiety is a subconscious emotional state and condition, solutions may need deal with the issue at a subconscious level.

Solutions should match problems

In the workplace, we typically address organisational issues at a conscious or “executive thinking” level. We intellectualise, operationalise and train our employees to use conscious decision making to resolve issues. This may not be suitable for dealing with anxiety as during periods of sustained or high anxiety the conscious state can be hijacked with emotion and automatic responses over riding logic or cognition. In order to deal with the automatic responses that anxiety can trigger, there is a need to reprogram, sometimes referred to as creating new neural pathways.

Is Hypnotherapy as a possible workplace mental health solution?

Hypnotherapy has developed as a subconscious therapy and has been used in clinical settings for many decades to help reduce symptoms of anxiety. It is a treatment in which the patient’s subconscious state is accessed to achieve a hypnotic state to reduce tension and other benefits, it taps into memories and patterns of behaviour allowing new neural pathways and more positive response patterns to be developed. This can be found to alleviate anxiety for patients in clinical settings, however there is little research around the utility of this subconscious interventions in workplace settings.

The perception of Hypnotherapy in workplaces?

Workplace psychosocial health and wellbeing programs that include mental health services are increasing, and organisational decision makers appear to be open to implementing new solutions, particular in relation to the growing issue of anxiety and performance, yet even though we could propose that there appears to be evidence that shows hypnotherapy is being used clinically to deal with the issue there is low and slow adoption of hypnotherapy in workplace settings. This may indicate that barriers may exist. Based on literature reviews in both academic journals as well as the public domain, barriers may include a lack of information, perceptions based on prior knowledge or a general lack of understanding and confidence in what hypnotherapy is and what it can provide as treatment for anxiety [22]. Identifying barriers to acceptance or adoption of hypnotherapy may in turn assist organisations in dealing with anxiety and in turn improve individual and workplace performance and productivity.

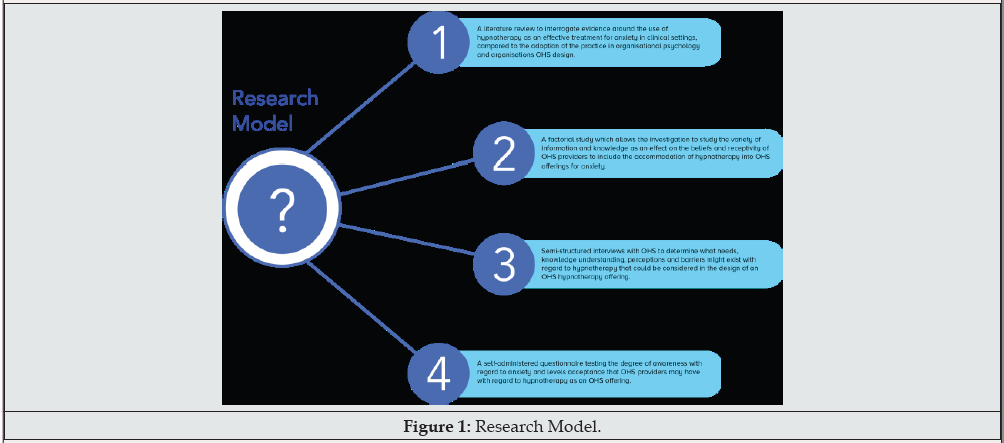

The study

This study included

a) A literature review around the use of hypnotherapy in clinical practice to establish the research context towards dealing with anxiety.

b) A self-administered Questionnaire (SAQ) in the form of an online Qualtrics survey distributed to leaders who had decision making responsibility regarding the development or implementation of mental health programs in workplaces in Australia.

c) Semi structured interviews were conducting with members of the same organisations to triangulate data and trends. Research questions focussed on

a) How is Hypnotherapy perceived by OHS practitioners as an intervention in response to anxiety in the workplace?

b) Are there perceived barriers affecting the adoption of the practice into OHS services?

Findings

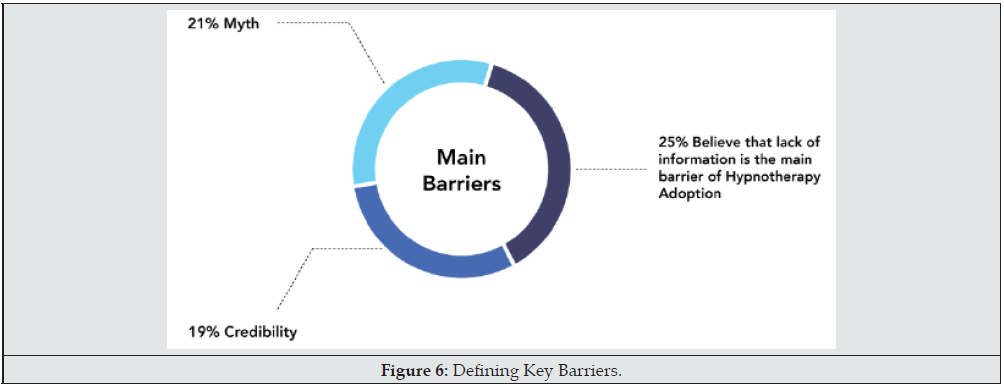

From the data extracted out of the open-ended questions, non-numerical textual descriptions, patterns in language for open questions were also determined using thematic analysis techniques. Initial interviews showed multiple factors influenced perceptions around this practice as shown in the world map in Figure 5. Common themes around barriers included Effectiveness (25%); Myth (21%); Credibility (19%); and Lack of information. Participants did not always have a clear understanding of what hypnosis is or how it works and negative perceptions in the media and popular culture drove inaccurate and often outlandish portrayal of hypnosis including the association with the theatrics of stage hypnosis. Misinformation about the practice included thoughts such as: a lack of knowledge; Hypnosis happens whilst individuals are asleep; individuals perform actions against their will; Individuals fake hypnotic states are vulnerable being under the influence of another and at risk of being taken advantage of with implied perceptions of “dancing chickens” fun fair and black magic for some participants there were other controversies regarding hypnosis and false memory.

Factor analysis was used to determine if information vs no information was a variable affecting perceptions

To determine if information might be a perceived barrier towards the receptivity of hypnotherapy, a self-administered survey was administered that followed the principles of factorial design, with the factor (discrete variable) of information versus no information being tested. This was considered a ‘with and without’ activity mimicking the use of an experimental control of whether more versus less information affects receptivity toward hypnotherapy (Figure 6).

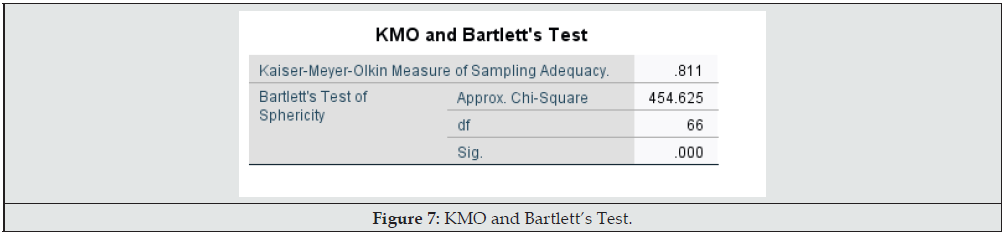

From 100 survey participants two groups were established. The groups were equal in size, comprising no less than 50 respondents in each group. The two groups were be labelled Group A and Group B. Within the survey, information regarding the field of hypnotherapy was provided to group A (WI) and not to group B (WOI). The survey questions remained the same. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy and Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was used on the data collected to test the strength of the partial correlation of the variable of information vs no information. KMO values closer to 1.0 are consider ideal while values less than 0.5 are unacceptable. Recently scholars have argued that a KMO of at least 0.80 is sufficient for factor analysis. From the KMO and Bartlett’s test the results showed a KMO measure of 0.811 which can be considered significant (Figure 7). We can conclude then that participant who took survey with information (WI) believed concept of hypnotheraphy was more helpful rather than participants who took the survey without information (WOI). Information is a factor in the perceptipnand possible acceptance towards cpmsogomg hynoptghera[py inclusion within workplace menal health [rorams.

i. Qualitative: Semi-structured interviews.

Several semi-structured interviews were held to:

a) Explore deeper perspectives on the issue.

b) Test what other barriers might exist to alternative solutions.

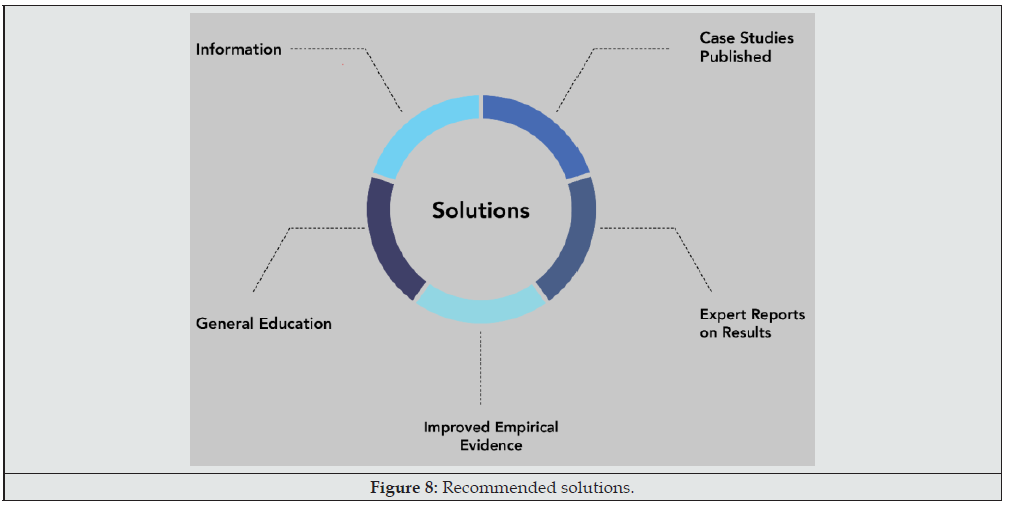

c) Determine what recommendations and resources might prove to be useful for OHS providers (Figure 8).

Testing the solutions

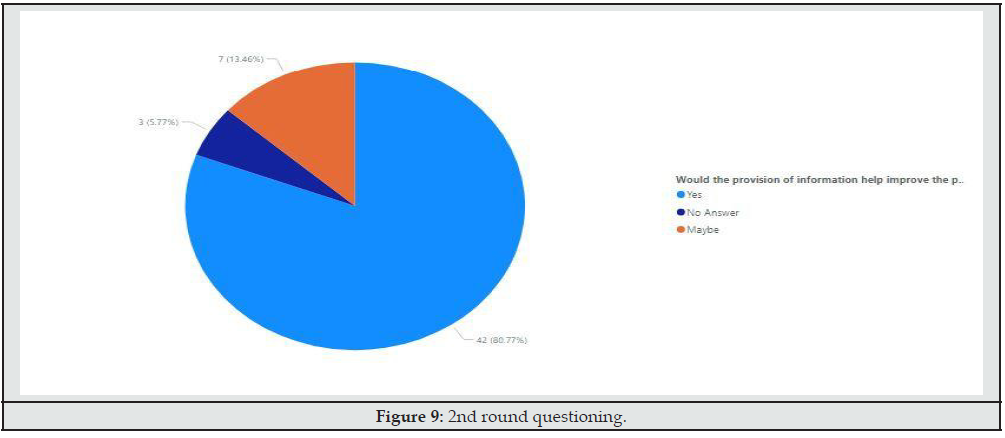

In second round questioning more 80% of participants answered “Yes” for the question “Would the provision of information (knowledge) help improve the perception and adoption of hypnotherapy to address Anxiety in the workplace?” (Figure 9).

Conclusion

If hypnotherapy was to be considered as a part of the solution to solve anxiety in the workplace, then proving more information and knowledge about the therapy should improve the chance of receptivity.

Other Factors

When analysing the data from the quantitative surveys demographic slices were considered. Participants older than 50 years of age were 5.3 times more likely to think it would be a solution and 1.4 times more likely to try it.

Future Research opportunities leading from this study

This study led to further questions around how other categories of employees or workforces may benefit.

Modern aspects of workforce change such as the gig economy, high performance and technological advances affecting work practices seem to be spreading rapidly and globally. Only a fraction of temporary workers and other members of the alternative workforce enjoy access to company-provided health benefits which include mental health programs. Also, during the height of Covid19 we have seen a trend towards work from home which means we could revisit questions about safety and health in the home/work environment. Work from home and telecommuting arrangements may reduce anxiety and injury risk by harmonizing work and family demands and minimizing daily commutes for some. Balanced against these presumed benefits are risks from loss of oversight, blurring of work and family roles, and isolation from peers which may have increased anxiety.

Research is needed to better understand gaps in the delivery of these programs to these workers. There needs to be investigation into whether the adjustments, learning demands, and workload pressures that may be created by new work systems and rapid technological advances that may be increasing anxiety.

Research must continue to assess organizational factors that have recognized associations with psychological factors affecting anxiety at work, as well as individual factors that may be considered for remediation.

Significance of continued study

Research in this space has real and of economic value for workplaces, if the moral imperative is not strong enough in itself. There is growing public awareness of the importance of good workplace mental health and wellbeing, as well as the moral, societal and business case for improving it.

References

- Baylor (2021) Findings in the Area of Anxiety Disorders Reported from Baylor University (Effect of Hypnosis on Anxiety: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial with Women in Postmenopause). Health & Medicine Week pp. 2698.

- Bertrams A, Englert C, Dickhäuser O, Baumeister RF (2013) Role of Self-Control Strength in the Relation Between Anxiety and Cognitive Performance. Emotion 13(4): 668-680.

- Eysenck MW, Calvo MG (1991) Anxiety and performance: The processing efficiency theory. Cognition and Emotion 6(6): 409-434.

- Salario A (2012). The Fear & Anxiety Solution: A Breakthrough Process for Healing and Empowerment with Your Subconscious Mind. Spirituality & Health Magazine, 15, 90+.

- Alladin A (2016) Cognitive Hypnotherapy for Accessing and Healing Emotional Injuries for Anxiety Disorders. Am J Clin Hypn 59(1): 24-46.

- Boxall P, Guthrie JP, Paauwe J (2016) Editorial introduction: progressing our understanding of the mediating variables linking HRM, employee well‐being and organisational performance. Human Resource Management Journal 26(2): 103-111.

- Wilson M (2008) From processing efficiency to attentional control: a mechanistic account of the anxiety-performance relationship. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 1(2): 184-201.

- Anand D, Wilt J, Revelle W (2017) Within-subject covariation between depression- and anxiety-related affect. Cogn Emot 31(5): 1055-1061.

- Schwartz BJ (2015) Mental Illness in the Workplace: Psychological Disability Management. Henry G Harder, Shannon L Wagner and Joshua A Rash (2014) Farnham, England: Gower Publishing, Ltd. 389 pp. The journal of nervous and mental disease 203(10): 812.

- Chen Y (2017) Factors Affecting Safety Performance of Construction Workers: Safety Climate, Interpersonal Conflicts at Work, and Resilience.

- Marciniak M, Lage MJ, Landbloom RP, Dunayevich E, Bowman L (2004) Medical and productivity costs of anxiety disorders: Case control study. Depression and Anxiety 19(2): 112-120.

- ADAA (2006) Anxiety disorders; Anxiety Disorders Association of America survey finds Americans report stress, anxiety. Mental Health Business Week, p. 9.

- Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, Finstad GL, Bondanini G, et al. (2020) COVID-19-Related Mental Health Effects in the Workplace: A Narrative Review. International journal of environmental research and public health 17(21): 7857.

- Van De Voorde K, Beijer S (2015) The role of employee HR attributions in the relationship between high‐performance work systems and employee outcomes. Human Resource Management Journal 25(1): 62-78.

- Rolls ET (2015) Limbic systems for emotion and for memory, but no single limbic system. Cortex: a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior 62: 119-157.

- Hartman D, Zimberoff D (2004) Corrective emotional experience in the therapeutic process. Journal of Heart Centred Therapies 7(2): 3-84.

- Kahneman D (2011) Thinking, fast and slow (1st ed) New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Alladin A (2016) Integrative CBT for anxiety disorders: an evidence-based approach to enhancing cognitive behavioral therapy with mindfulness and hypnotherapy. Chichester, England: Wiley Blackwell.

- Beck A (1980) Cognitive Therapy of Depression. Psychological Medicine 10(4): 802.

- Speigel RB (2011) The integration of Heart-centred Hypnotherapy and Targeted Medical Hypnosis in the surgical/emergency medicine milieu. (Report). Journal of Heart centred Therapies 14(2): 87.

- Klissourov, G (2018) Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness Magnitude of Hypnosis on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Treatment. In C Lesniak & S Little (Eds), ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Gallagher C, Underhill E, Rimmer M (2003) Occupational safety and health management systems in Australia: barriers to success. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety 1(2): 67-81.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...