Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Alcohol Sachets an Endemic Problem in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do the Alcohol Sachet Bans in Africa Achieve the Policy Goals on Access and Availability Volume 8 - Issue 3

Kasirye Rogers (Ph.D.)*, Moses Kinobi, Anna Nabulya, Barbara Nakijoba and Mutaawe Rogers

- Uganda Youth Development Link, Uganda

Received: September 02, 2024; Published: September 11, 2024

Corresponding author: Kasirye Rogers (Ph.D.), Uganda Youth Development Link, Uganda.

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2024.08.000286

Abstract

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Background: Packaging alcohol in small quantities appears to be very popular in sub-Saharan African countries. This region represents itself amongst the largest consumer of easily accessible alcohol (WHO, 2018). Packaging and selling alcohol in sachets of certain amounts below 200 millilitres (mls) is common. There have been efforts by governments in the region to ban alcohol packed in small sachets (small quantities) during the period 2010-2022. Packing alcohol in sachets was making alcohol easily and widely available – causing alcohol-related problems. Sub-Saharan Africa has experienced high levels of alcohol poisoning and young people are turning to drinking (UYDEL 2012, 2014, 2022).

Method: Using desk reviews and web-based research for information, the study examined the methods and delivery of such directives that banned alcohol packaged in sachets in 10 selected sub-Saharan countries, their implementation and impact. We explored the legal regimes and social actors concerned with the bans.

Discussion: Over 10 African governments have banned alcohol packed in sachets. Information showed an increase in awareness about alcohol harm and a temporary drop in the drinking of alcohol. The ban led to a shift or migration from packing alcohol in polythene bags to packing it in plastic bottles (single use) with a minimum of 200mls. Lobbying and resistance by brewers in some countries delayed and violated the ban. The enforcement of the ban varied depending on who issued the ban, human resource, cooperation of the community and heightened awareness about the packaging of alcohol in sachets. The banning of minimal packaging of alcohol in sachets could be easily implemented with laws regarding weights and measures which provide a minimum standard and eliminate small amounts of certain products.

Conclusion: The intended benefits of the ban regarding accessibility, availability and acceptability appeared to work well in short term, more in the city as compared to rural areas. Availability and access in the long run are not affected as brewers used plastic bottles to pack same amount of alcohol and many relied on local brew. There is need to explore all means that help reduce the exposure of alcohol to young people buy eliminating small packaging in sachets, small plastic bottles and single-use plastic bottles.

Introduction

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Sub-Saharan countries of Africa are currently experiencing an increase in health and negative social effects believed to be due to the heavy consumption of cheaply and widely available spirits in the region. Alcohol misuse is a major global health threat, associated with more than 200 burden of disease and injury conditions (World Health Organization [WHO], 2018). Similarly, WHO indicates packing alcohol in small sachets has become a widespread problem in Africa and has both significant social and economic negative impacts on individuals and society. The WHO estimates that approximately 3 million deaths worldwide resulted from harmful use of alcohol in 2016 (WHO, 2018). Globally, the African region has the highest age-standardized alcohol-attributable burden of disease and injury (WHO, 2018). Factors related to underage drinking in sub-Saharan Africa include peer pressure, role modelling by parents and family members, poor social and coping skills, positive expectancies from drinking and increased alcohol availability. Literature by WHO attributes the increase in alcohol use in developing countries to the expansion of the global alcohol market, packaging, pricing and aggressive marketing techniques. Alcohol intake among adolescents is associated with lower academic achievement, school drop-out, risky sexual behaviour, poor health outcomes and a high likelihood of alcohol dependency in adulthood. Alcohol in sachets forms a bulk of the illicit alcohol which is unregistered, contributing to high consumption and local revenue. The financial and economic doldrums after Covid-19 appear to be attracting many small-scale investors and households to start small-scale alcohol production that escalates small packages. Price and packaging are two important factors that influence availability and consumption levels. Alcohol continues to pose a great burden in Africa (WHO, 2018) and getting normalized at a faster rate through packaging and intensive marketing [1] and the consequences of alcohol for the youth as a result of use which many times is episodic (binge) [2] are a great concern [3]. This can lead violence and risky sexual behaviours [1].

Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

The years beginning 2012, African governments acknowledged the dangers of packing alcohol in small quantities as a danger to the children and youth, as well as the content therein. It is reported that governments instituted bans on alcohol packed in sachets. Most work written on sachets has been limited to newspaper reports in Africa and such information has not been fully synchronized. Yet a bigger picture of the bans in African countries is needed to draw lessons in availability and enforcement of alcohol sachet bans so as to protect children in the future since alcohol spells more harm for people and communities [4]. Alcohol is quite cheap, easily available and heavily marketed. This fuels widespread alcohol harm and drains much needed resources from society [4]. Countries like Nigeria where spirits are packed in sachets contain between 40- 60% alcohol (ethanol). Sachet liquors are readily available for sale at different outlets including beer shops, bus stations, pharmaceutical shops and supermarkets [5]. Generally, in Africa laws regarding alcohol are poorly enforced as alcohol is sold in all places [5,6] with high levels of alcohol use in sub-Saharan Africa. Main Objective of the study

1. To examine the effectiveness of the alcohol sachet bans in African countries.

2. To understand the impact of alcohol sachet bans on addressing issues of accessibility and reduction of alcohol-related harm in Africa.

Methodology

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

We reviewed and examined available information on the web to download all information related to alcohol sachets ban in sub- Saharan Africa. All African countries which had banned alcohol sachets from 2010-22 with reported actions on bans were eligible for the study. The source of the information was mainly the Internet and desk reviews. The qualitative data collected was organized into different themes as it appeared to emerge based on the literature review and analysed thematically in line with the objectives. Using thematic analysis, we examined the meaning and symbolic content of the data as it relates to the topic highlighted above, to be able to identify, analyse and report patterns within the data. The study limited itself to information on the ban of alcohol sachets only. We were interested in parameters such as packaging volume. How do alcohol sachets increase availability, accessibility and acceptability? The ban and how long it took be effectively enforced and challenges of implementation.

Results

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Alcohol sachets ban between 2010-2022

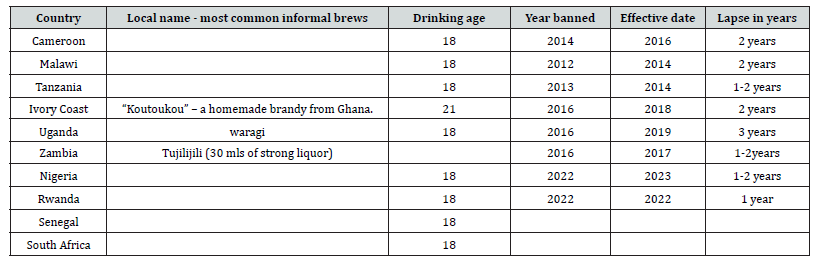

The information collected indicated 10 countries in sub- Saharan Africa had instituted alcohol sachet bans between 2010 and 2022 (see table 1 below). Of the 10 countries, the information showed that seven had banned alcohol sachets and tot packs and their information was readily available. Two countries, Senegal and South Africa reportedly banned the sachets, but we were unable to get detailed information regarding the bans. Ten African countries had banned alcohol sachets by early 2023.

Availability, Access and acceptability

Tot packs and alcohol sachets, price and the reasons for the ban

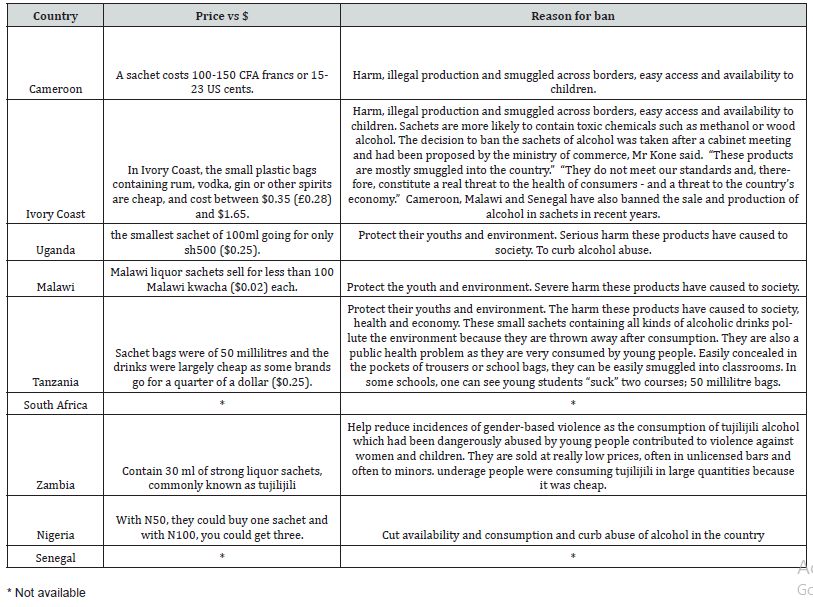

We noted the least package (volume of the alcohol sachets varied in most countries and for most of these the volume was around 50 millilitres (mls), except in Uganda where a smaller packaging of 25 mls had been reported. The price of a sachet of alcohol on average was 10 US cents across board. The alcohol content (ABV1) varied in all countries and the majority were making alcohol from ethanol products. The findings indicated that more brewers used methanol and wood ethanol. In Ivory coast, for example, it was reported that banned sachets are more likely to contain toxic chemicals such as methanol or wood alcohol. In Tanzania, the sachet bags were of 50 millilitres and the drinks were largely cheap as some brands go for a quarter of a dollar. In Uganda, the alcohol sold in smallest sachet of 100ml going for only sh500 ($,025). By then (2015), 75% of the alcohol manufactured was sold in sachets while the rest (25%) is sold was bottles. In Cameroon a sachet costs 100-150 CFA francs or 15-23 US cents. In Malawi, liquor sachet sells for less than 100 Malawi kwacha ($0.02) each. In Nigeria, with N50, they could buy one sachet and with N100, you could get three (Table 1).

FOOT NOTES

1The number of units in a drink can be calculated from the alcohol by volume (ABV) and the size of the drink. The higher the ABV, the stronger the drink.

Table 1: Selected African countries that banned the production, importation and sale of alcohol in sachets.

Names for local sachets varied across all countries. Many had names of great persons and celebrities that entice young people to drink and imagine so. Others were not readily available. To young people this was acceptable in terms of price and content irrespective of the toxicity of the substance therein.

Several reasons advanced for alcohol sachet ban in African countries

Alcohol sachets as a public health issue: Several reasons were advanced by the countries that banned sachet alcohol as provided in the Table 2 below, common amongst them were to reduce availability and reduce consumption among young people as well as the protection of children and youth from the harm caused by the intoxicating substances. In 2022, Rwanda banned the packaging of alcoholic drinks in plastic bottles, and it is the only country that has taken such an action (Table 2).

Alcohol sachets as an environmental degradation issue: In Tanzania, as a case study showed, it was reported that these small sachets containing all kinds of alcoholic drinks pollute the environment because they are thrown away after consumption.

Perception and status of alcohol sachets

“The attitude of the government which granted these periods of moratorium is sickening,” says the FOCACO president, condemning the “blank cheque to these producers to continue poisoning Cameroonians”. Such brews are “very toxic for the body”, warns gastroenterologist Djomo Kopa at Douala general hospital. “We don’t know the quantity of alcohol in each sachet, nor its strength nor exact make-up because it’s usually adulterated whisky,” she says. “The legal ban from 2014, which has seen endless moratoriums, outlaw’s plastic sachets of alcohol,” notes Ayissi Abena. In Nigeria, it was revealed that with Naira (N) N50 one can buy a sachet and for N100 three of them. “These three sachets are N100. If I finish taking them, I will go home satisfied, but one bottle of beer is N200 or N250, I have to drink two bottles to get the amount of satisfaction. I get with these sachets so it’s expensive. This one gets me high, and I go home,” says one consumer”. An Alcohol seller mentioned that “It is the sachet drinks that attract most customers,” she says. “You can’t even compare them with beer. Not many people drink beer because of the price. These ones sell very well.”

Both small and large-scale brewers were packaging alcohol in sachets and Uganda Breweries Limited in Uganda is a case in point. In Nigeria, all the three major brewers were doing likewise and proud of the growing trend. Origin bottlers sold at N50 by Guinness Nigeria suggests that the company is already paying attention to the growing trend. Reports in Tanzania indicated that some sachets are selling better than sodas in some places. After drinking the contents, patrons often throw the empty sachets onto the roads and into the sewers.

In Uganda a one director at Uganda Breweries limited (UBL) noted that,

We are open to supporting government in the ban of alcohol sold in sachets. We believe the industry has not been as responsible as it should be when it comes to packaging alcohol in sachets. The privilege of doing so has been abused by some industry players and therefore regulation in this area will solve that abuse. When you look out in the market, some sachets are being sold at sh600 ($0.25) but ours that are packed in same quantity is retailed at between sh1,500-2,000 after factoring in all factors of production. So, we wonder how other players get the price of sh600 and remain profitable. There can only be two things; either they are taking shortcuts in the manufacturing process which means they are putting consumers at risk of getting medical problems or they are taking shortcuts in respect to payment of duty which means government is losing revenue.

Factors behind governments’ instituting of alcohol bans

Alcohol sold in sachets has become a danger especially to the youth because it is cheap and easily accessible. According to Ministry of Trade data, currently, 75% of the alcohol manufactured in Uganda is sold in sachets while the rest (25%) is sold in bottles.

Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Big brewers in Uganda appeared to have welcomed the ban as many anticipated an increase in their share. One UBL manager asked how government should go about preventing illicit alcohol on the market. Market research has showed us that 70% of alcohol consumed in Uganda is either informal or illicit. Informal alcohol per say is not bad. Illicit alcohol is what is bad because it is produced in the backyard without adhering to the required standards and some is smuggled into the country without paying tax. The third type of illicit alcohol in this category is called counterfeit. We, therefore, think the time is right for the government to come out and pronounce itself against illicit alcohol because of the dangers related to health and reduced tax collection. In terms of consumption, Ugandans consume 110 million litres of alcohol and 67.7 million of this is illicit while only 43 % is from the formal, regulated, taxed sector. The lack of consistent or proper enforcement, inspection and registration of traders and transactions has allowed illicit production to flourish.

Case of Rwanda

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Rwanda Food and Drugs Authority (FDA) has prohibited the packaging of alcoholic drinks in plastic bottles as they pose a threat to both consumers’ health and the environment. Rwanda FDA noted that packaging alcoholic drinks in plastic bottles leads to adulteration as some of those packages are made of chemicals which get re-activated and dissolved in the drink following prolonged exposure to heat and contact with alcohol, thus posing a health risk to consumers. It was reported that alcoholic drink makers in the country have accepted the move but have called for the establishment of a local glass packaging factory to ensure regular and affordable supply of the packaging materials in the country. Some of the manufacturers in the country had already made the shift prior to the directive but lament that imported glass bottles are too costly, resulting in high production costs which at times are transferred to the end consumer, making the products expensive. In order to ensure the quality and safety of alcoholic drinks on the Rwandan market, Rwanda FDA has advised all the distributors to stop receiving and distributing or selling alcoholic drinks packaged in plastic bottles and to report manufacturers who use the banned bottles. The ban also impacts exports from Uganda, Burundi and Tanzania, a move likely to impact her neighbours (Rwanda Times, 2023).

https://www.foodbusinessafrica.com/rwanda-foodand- drugs-authority-bans-packaging-of-alcoholic-drinks-inplastic- bottles/#:~:text=The%20ban%20in%20Rwanda%20 comes,in%20sachets%20by%202023%2F2024.

Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Significant failure to monitor and enforce the ban. We noted in all countries that banned sachets, there was a significant failure to monitor local small back-door producers. Smuggling across porous borders was endemic and drinkers crossing the borders, for example in Zambia and Uganda, were noted. Local manufacturing companies were not monitored to ensure that they do not produce illegal substances that will end up destroying the moral fibre of the nation. Many times, such brewers wanted time to delay migrating and preferred a phased manner as they produced and sold their products and argued that they had imported so many raw materials that migration would result in their incurring losses. In Nigeria, the producers of alcohol in sachets and small volumes agreed to reduce production by 50% with effect from January 31st, 2022, while ensuring the products are completely phased out in the country by January 31st, 2024.

Lack of alternative methods of packaging. In Rwanda there was a call to establish a glass factory to supply the packaging as recommended by Government. In Nigeria, the National Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) suggested that these companies be given some time to adjust and look for other forms of packaging for their products.

Court litigation. In Zambia, the Lusaka High Court rejected a second attempt by 15 liquor companies to stay the government’s decision to ban the manufacturing and supplying of a highly potent alcoholic drink commonly known as tujilijili.

Cross-border drinking. Some Zambian residents of the border town of Nakonde have continued consuming tujilijili except this time around, they cross into neighbouring Tanzania to take their drink and then stagger back onto the Zambian side in a drunken stupor. The residents are capitalising on the fact that the statutory instrument signed by the local government minister, Nkandu Luo, did not affect Tunduma, which is part of Tanzania.

Failure to comply. In Uganda, information shared revealed that 11 out of 26 alcohol-producing companies have not yet complied with the Ugandan government’s ban on the production and sale of alcohol in sachets by 2016.

Use of media to criticise the ban: In Zambia, there was a strong lobby criticising the ban: as shown below,

“Foolish thinking. You don’t ban, you regulate and phase out slowly. What happens to all jobs, what happens to all stocks still available? What happens to the machines? Poor planning, if you gave people a licence, you also need to give them time to re-direct their businesses. +Meanwhile you increase taxes tenfold so that the product becomes expensive immediately. That’s not how we run a country.” (The times of Zambia, 2012).

Alcohol poisoning. This has been one of the major pushes. For example, in Uganda it was noted that although the data on the effects of alcohol-related harm in Uganda is limited, in 2016 the WHO estimated that alcohol killed 2,851 people due to liver damage, made 3,900 perish in road accidents and 1,514 people from cancer resulting from its consumption.

Limited human resource capacity and poor enforcement. Mr Fred Okiria, the manager of alcohol beverage co-ordination at the Alcohol Industry Association of Uganda (AIAU), told the Daily Monitor newspaper (4th August 2020) that hundreds of manufacturers were still producing the said alcohol products.

“The biggest challenge we are facing is the illicit alcohol which is affecting our trade and risking the health of consumers. More than 200 companies in the country are manufacturing the products and dumping them in the consumer market,” he said.

Mr Okiria blamed this on limited human resource capacity and poor enforcement by the Uganda National Bureau of Standards (UNBS) as the cause of the dangerous trend. “The products have the wrong physical address, no UNBS mark or digital tax stamp and they are sold at mere 1,000 shillings for a 200mls package unlike standard ones that are sold at 2,000 shillings,” he added.

Collaboration from the concerned members of the public, the manufacturers and a lot of dilly-dallying.

In Uganda, UNBS which was s enforcing the ban says that from 2017 to date, they have done massive enforcement and stopped the production of the said drinks by 37 alcohol-manufacturing companies across the country. Ms Sylvia Kirabo, the UNBS principal public relations officer, noted that the smuggling of the banned products from foreign countries into Uganda by unscrupulous traders is also sustaining the trade in illicit alcohol.

Directives for Banning the Alcohol Sachets

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Nature of alcohol sachets. The bans were largely ministerial directives, except in Tanzania where President John Pombe Magufuli issued a presidential decree banning alcohol sachets. These took the form of directives to limit the packaging volume to 200mls, transportation, export and distribution. The emphasis has been more on the packages not the content therein.

Time duration. Data indicated that the duration and actual ban varied from country to country. It was only in Tanzania where it took immediate effect in 2017; a lapse of three months. In other countries such as Zambia, Malawi and Ivory Coast it took two years. In countries like Uganda, it took more than three years. There was a lot of fights on the floor of Parliament involving the Ministry of Health, Parliament and Ministry of Trade that was responsible for enforcing the ban. The Ministry of Health had to retract its ban after realising that it was unenforceable.

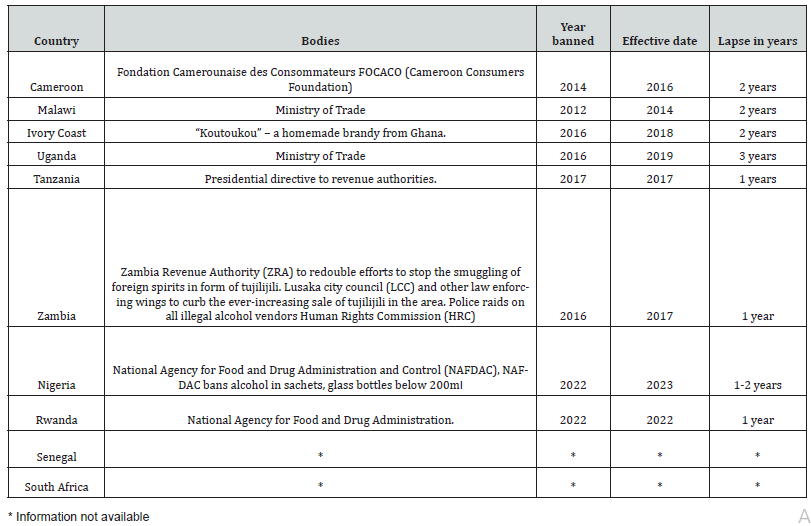

Bodies responsible for enforcement of the ban. Information available indicated that countries that enforced the ban had different agencies to oversee the enforcement of the ban. In some countries agencies working alone and others in unison, including several food and drugs bureaus; national bureaus of standards under the trade ministries, ministries of health and ministerial directives. We noted that the President’s office in Tanzania took the lead in enforcing the ban during Magufuli’s presidency. In Nigeria, it was NAFDAC and in Rwanda it was the government itself that took the lead. Other agencies such as the police, tax and revenue authorities and local governments have also been working in unison to enforce the ban. Agencies concerned with food and drugs-related matters appear to be the ones spearheading the ban and enforcements (Table 3).

Table 3: Showing bodies responsible for enforcement of the ban on production and sale of alcohol in sachets.

We noted that countries where enforcement was combined with the Ministry of trade and food and drug bodies the bans were more effective.

Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Adherence to the ban varied considerably amongst countries as information shows that in almost each country except Tanzania there was a lot of dilly-dallying with meetings intended to delay or avoid the ban. A case in point was Uganda where the Ministry of Trade and Industry under the influence of big alcohol brewers strongly opposed the ban on the floor of Parliament. The ban that had been instituted by the Ministry of Health collapsed. After the September 2017 directive, the trade minister was seen and heard in June 2018 announcing a new directive for a 2019 ban on sachet alcohol.

Ministry of Trade and the alcohol industry road map in countries

In most countries that witnessed the enforced alcohol bans, there were many meetings between Ministry of Trade and the alcohol industry that agreed on a road map to phase out alcohol sachet packaging. Most of these road maps were unclear and centred more on deadlines rather than tracking packaging. They ignored the private sector and civil society. A case was seen in Uganda, in an unusual way where a joint meeting with the alcohol industry, held under the umbrella of the Uganda Alcohol Industry Association (UAIA) and the Ministry of Trade and the alcohol industry agreed on a road map to procure, install and commission new bottle packaging production equipment, including building new factory premises for new technology bottling machinery. This process took more than two years and purportedly attracted several investments for bottling equipment to enable the transition. At the time, the trade minister was heard saying: “This means that the production and packaging of alcohol should transit from packaging in sachets to packaging and sale in plastic and glass bottles, 200mls minimum.

Alcohol industry lobbies against evidence-based alcohol policy measures

The alcohol industry in the 10 African countries mentioned earlier not only failed to fully comply with the alcohol sachet ban (production and sale), but also used the opportunities to engage with the trade ministry to lobby against evidence-based and the WHO recommended alcohol policy measures including (WHO alcohol best buys). This entire process has involved engaging with the alcohol industry so closely but falling way short of the long-announced alcohol sachet ban. The alcohol industry’s representatives claim that about 50% of alcohol in Africa is illicit due to high taxation – even as they continue to fail to stop producing and selling sachet alcohol. Such a claim is far from the WHO (2018) evidence that shows that alcohol taxation is a triple win measure for health, development and government revenue and that current levels of taxation are by far too low to prevent and reduce alcohol harm effectively.

Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

“In Cameroon since we can’t halt the supply, we are trying to promote awareness,” says Ayissi Abena, who runs the Cameroon Consumers Foundation (FOCACO).

Counterargument against the ban, policy and case for taxation, employment and incomes

The Alcohol Manufacturers Association of Malawi insisted that the sale and packaging of the liquor sachets is not illegal. They argued that they meet regulations set up by the Malawi Bureau of Standards and comply with Malawi Companies Act. The association said that the government should instead create a comprehensive policy, involving all stakeholders, to restrict the sale of alcohol to minors, and to move the points of sale away from highways and school zones. The Malawi government tried to ban the packaging and sale of blackberries in May 2013, but manufacturers successfully obtained a court injunction to have the ban overturned. Now, several NGOs are petitioning to reinstate the moratorium on liquor sachets on public health grounds.

Court injunctions against the ban

It was noted that there was some resistance from alcohol producers, and they even went to court to protest the ban. A good example was the Lusaka Zambia High Court that rejected the second attempt by 15 liquor companies to stay the government’s decision to ban the manufacturing and supplying of very potent alcoholic drinks commonly known as tujilijili. Justice Dominic Sichinga maintained the court’s decision to deny the 15 liquor companies’ bid to stay the decision to ban the manufacturing, importation, exporting, selling and supply of tujilijili when the matter came up for interparty.

Smuggling of sachets from neighbouring countries

In Zambia it was noted that it was worrying that huge supplies of the illegal products were still coming into the country from the neighbouring countries. In Ivory Coast, tracking the sales of alcohol sachets, many containing spirits distilled from palm wine is difficult because they are often produced outside regulated markets.

Role of the media in the alcohol sachet ban and enforcement

The media’s response and support towards the ban varied greatly. In some countries, the media was found to be in support of those with economic interests that run counter to the ban despite the obvious health risks.

Nigeria’s alcohol bans an attack on consumers freedom, small business owners

OLUMAYOWA OKEDIRAN, SEPTEMBER 24, 2020

Nigeria’s ban on alcohol recently made the rounds in the news on local media outlets. The announcement disclosed in a statement by the National Agency for Foods and Drugs Administration and Control (NAFDAC) director-general, Prof. Christianah Mojisola Adeyeye, stated that the federal government had issued directives targeted at phasing out the sale and consumption of alcohol in sachets and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles. This means that the regulatory agency will no longer register new products in sachet and small volume PET or glass bottles above 30 per cent Alcohol by Volume (ABV) and also mandated alcohol companies to drive down production by at least 50% enforceable for January 31, 2020. This article highlights the effect of the ban on small business owners and the limitation to the freedom of consumer choice.

The media annotated that this partial ban on alcohol seems to only be targeted at a specific set of people – low-income earners. The dominant consumers of alcohol in sachets and small bottles are low-income earners, just as the predominant retailers of alcohol in this packaging are small businesses who own small kiosks or even hawk their wares. In fact, the reason big companies often go the route of selling alcohol in sachets and small packs is because that is the only way low-income earners can afford them. Shutting out this access is in fact seeking to erase the end of one market. This prohibitionist approach effectively cuts off many low-income earners from participating in the alcohol market. This is likely to cause economically disadvantaged people to buy alcohol in excess of what their finances ordinarily allow as affordable options are being taken out of the market.

It essentially signals to low-income earners to buy more alcohol since the only option they are left with is to buy alcohol in bigger packaging. Also, by making the sale of alcohol in sachets illegal, there is also the possibility of certain individuals taking advantage of the demand for sachet alcohol by illegally apportioning alcohol in sachets and other smaller containers under potentially unhygienic conditions.

Beyond the suffocation of economic activities at the base of the pyramid, an outright ban conflicts with the freedom of consumers to choose and the importance of markets. This is another example of the Nigerian government’s overarching involvement in the choices of Nigerians. The agency had highlighted that uncontrolled access and availability of high concentration alcohol contribute to substance and alcohol abuse in Nigeria transitioning into a negative impact in the society. One of the best approaches to curbing substance use has been used in the tobacco industry. Without banning its usage, members of the public are made aware of the consequences of tobacco use and allowed to make their own decisions.

The Nigerian government has become increasingly overreaching in its responsibilities by taking away decisions that should ideally be left to consumers. Usually, when a group of people makes decisions for others, it does this with its own bias and without much knowledge of the motives of the eventual consumers. The truth is that consumers are usually aware of the risks and benefits associated with products they use before consumption. However, the most ideal approach should be to make any new information about certain products publicly available so that consumers can have more information that can help them make informed decisions. Due to the absence of a perfect product, consumers often always juxtapose the risks and benefits associated with each product they consume with alternatives available. While certain persons will embrace certain risks, others are less likely to do so or may simply choose preferable risks. Banning products reduces the alternatives for users, limiting the available solutions to their problems as everyone who makes a purchase of an item is looking to solve an important problem. Banning the sale of alcohol as well as instructing companies to deliberately lower their production below their capacities and operate at 50 percent efficiency irrespective of market demand is detrimental to an economy. It is also a direct affront on the freedoms that consumers should have in an open market.

https://consumerchoicecenter.org/nigerias-alcohol-ban-is-anattack- on-consumers-freedom-small-business-owners/

https://www.thecable.ng/fg-moves-to-ban-alcohol-in-sachets

Impact of ban on alcohol consumption

Bans affect the availability of alcohol in a number of ways (consumption, export, import, smuggling, decline in sales and affordability) for those at the bottom of the pyramid who form majority of their clients especially children, youth and young adults.

Reduced consumption, affects sales and reduces tax

A study done in Uganda by Mbona et al., (2022) concluded that in Uganda the availability of (a) alcohol and (b) sachet alcohol was significantly affected by the ban. Before the ban, 69% of all establishments sold alcohol; there was a significant reduction in alcohol availability after enactment of the ban to 43% of the establishments (p < .001). This reduction was observed in offpremises establishments (p <.001), but not in on-premises establishments (p =710). Additionally, before the sachet alcohol ban, 52% of all establishments sold sachet alcohol. However, there was a significant reduction in sachet availability after enactment of the ban (1.4%, p < .001). Legislation banning the manufacture and sale of sachet alcohol has the potential to reduce the availability of sachets.

The sachet alcohol ban may have led to reduced sachet alcohol availability in retail food and beverage establishments. An inspection completed three months after the enactment of the sachet alcohol ban by the Uganda National Bureau of Standards (Uganda’s standard regulatory authority) found that 37 alcoholmanufacturing companies were still producing sachet alcohol in July 2019 (Gahene, 2019). It was also envisaged in Nigeria that impact of the ban would be felt more by the small-scale players in this segment and could be a win for other large-scale established players.

Closure of some alcohol factories

Information revealed that some brewers did close as is the case in Uganda. Interestingly, by instituting the ban Uganda had 26 companies packing alcohol in sachets by 2002. However, there were over 36 new companies emerging in Uganda. A ban provides and invites many other to invest in this area. Bans are only on the packaging materials and volume, not the actual product.

Increased smuggling from neighbouring countries

In Zambia, it was noted that it is worrying that huge supplies of the illegal products are still coming into the country from the neighbouring countries. It is no secret that many youths in Zambia have died after consuming copious amounts of the outlawed alcohol. The retailers that sell alcohol in sachets and small bottles are small shops and kiosks. Countries like Tanzania, Kenya and Rwanda also complained about the smuggling of alcohol sachets from Uganda most especially at the porous border points.

Underground production and marketing

In Cameroon despite a ban, ‘whisky sachets’ remain very popular. Eight years later, in Yaounde and the economic capital Douala, brightly coloured packs of sachets of Bullet, Fighter, Shoot and Shooter seem to be everywhere.

Change in strategy in some countries

Many alcohol bans were instituted during COVID-19 and many brewers changed track by advertising on social media and doing home deliveries which caused an increase in consumption. Not selling in kiosks and on streets but via home deliveries may escalate consumption further. In Cameroon, the plastic and alcohol mix can be toxic, he says, but berates above all the legal vacuum created by a succession of moratoriums that has allowed producers to evade all safety checks. “They don’t have any compliance certificates and use a lot of methanol.” In Nigeria today, all milk and tea brands have adopted the strategy of targeting low-income earners with sachets packs. It is becoming the most effective way to stay afloat as average per capita income in Africa’s largest economy continues to shrink. “Given the relatively high inflation rate,” Adi notes, “concerned budget of households and individual consumers, some will shift away from the higher end products to lower quality but more affordable varieties. The determining factor for consumers is affordability rather than quality,”( Nigeria’s National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control leader).

Heath and social consequences rise

For those who really want to drink still have other options now that tujilijili in Zambia is gone. The ban does seem to have had an effect, as the number of people admitted to Chainama Hills Hospital with alcohol intoxication seems to have dropped already. “In the first days after it was banned, we saw more people suffering from withdrawal symptoms because they could no longer get the sachets,” says Alice Phiri, a nurse at the hospital. However, she now sees that the number has dropped.

“Of course, Kachasu is still there, but that is sold in bigger, more expensive bottles and is not so easy to carry,” she explains. “I have worked here for more than 20 years. Before tujilijili, when we only had kachasu, such patients were rare.” “My own son, who also used to work here, was fired because of abusing alcohol. I salute the government for banning these things,” she adds. But the manufacturers and traders of the sachets have not given up and are still fighting the decision to ban tujilijili in court. [7]

Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Case in Zambia

Several countries have also had discussions on how to deal with the problem. Zambia has now taken the lead in eradicating this problem by banning both the productions and sale of liquor sachets. In Zambia they are popularly known as tujilijili. The ban was announced by local government and housing minister Nkandu Luo. Professor Luo has for many years been active in alcohol research and alcohol policies in Zambia. Luo has since signed a statutory instrument on ‘Liquor Licensing (intoxicating liquor quantities and packaging) Regulation 2012 on the banning of tujilijili.’ She also said that any license issued in respect of manufacture, import, export, sale or supply of intoxicating liquor prohibited under the regulation has been revoked.

The illicit spirits known in local parlance as tujilijili were back on the streets. Young people have been abusing these illegal substances to induce ecstasy and in most instances the consequences have been fatal.

The government banned tujilijili in 2012 following concerns about its side-effects. There was hope among parents that their children would not easily access alcohol.

The substances now come under different names like Konyagi, Kiroba and Samson. A sachet at COMESA market in Lusaka costs K15, while at City and Soweto markets the product costs K14 a sachet. They come in packets containing 20 sachets. The sachets contain 30ml of potent alcohol. Samson has 40 percent alcohol content while Konyagi has between 35 to 60 percent alcohol content. Kiroba has 45 percent. Reports suggest that the products are smuggled into Zambia from Tanzania and Kenya. Targeting lowincome earners. The dominant consumers of alcohol in sachets and small bottles are low-income earners, just as the predominant retailers of alcohol in this packaging are small businesses who own small kiosks or even hawk their wares.

South Africa’s economic recovery complicated by costs of prohibition

Like the bootleg liquor which has flooded South Africa in recent months, this low-cost alcohol is frequently laced with ethanol and other impurities, including heavy metals and is manufactured in hazardous working environments, where poorly paid workers risk horrific burns from frequent explosions. The widespread consumption of unregulated alcohol led to a whole host of problems in Uganda, exacerbating chronic levels of poverty and sparking an epidemic of mental health problems and cases of blindness due to the toxic chemicals found in this homebrew.

Alcohol sachets ban and need for increased taxation revenue

Uganda, however, is now taking concrete steps towards more effectively regulating liquor in order to bring every alcohol product into the taxation curve. It has taken a leaf out of its neighbours’ books who have managed to effectively crack down on the scourge of illicit and unsafe alcohol. Kenya, for example, has won praise for its Excisable Goods Management System (EGMS)-initially focused on alcoholic drinks and cigarettes, the cutting-edge tax stamps were subsequently extended to bottled water and other drinkswhich has helped dramatically increase excise collection.

Since introducing the EGMS scheme, the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) has shut down hundreds of illegal producers, resulting in more than 800 prosecutions. The KRA uses intelligence from manufacturers and importers of legitimate products – and from its own testing and enforcement teams – to quickly root out contraband goods before they can be widely distributed. Tanzania has also ramped up its oversight of alcohol after implementing its Electronic Tax Stamps (ETS) system in January 2019. The scheme has played an essential role in curbing the proliferation of counterfeit products on the Tanzanian market and has brought in significant tax revenue. Just three months after the scheme was put in place, Tanzanian tax officials estimated that the ETS system was helping them recoup some $1.7 million a month. Over the course of the past financial year, the scheme pushed tax revenues up by an impressive 34%, prompting Dar es Salaam to roll out the system for bottled water and soft drinks as well.

Uganda is now in the process of implementing a similar scheme, despite manufacturers having repeatedly tried to derail the rollout and has seen encouraging results so far. Under the system, Digital Tax Stamps (DTS) are applied to eligible goods, allowing tax revenues to be more easily collected on alcohol, soft drinks and tobacco products, whether locally manufactured or imported. Earlier this year, the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA) announced 139 drinks producers – including 84 spirits companies – were now contributing to tax revenues after years of evasion. The successful deployments of these electronic tracking systems in East Africa have also pushed governments elsewhere on the continent to pursue similar solutions2.

Discussion

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Over 10 African governments banned alcohol packed in sachets and tot packs of below 200mls. The enforcement of the ban varied from country to country. The bans were issued as national statutory directives and limited the enforcement to police and national drug enforcement agencies. The food and drug-related agencies appear to be the main bodies spearheading the bans and enforcements. Directives (from ministers and president were more effective as was done in Tanzania). In some instances, the beginning of the enforcement delayed for so long, for over two years in some cases. There was an increase in awareness about the harm alcohol does to one’s body and a temporary drop in drinking alcohol. Some countries followed up and tracked the ministerial directives and enforced them, while others did not. The ban led to a shift or migration from packing alcohol in polythene bags to pouring it into plastic bottles with a minimum of 100mls. Lobbying of brewers delayed and, in some countries, they worked to delay or violated the ban. It became clear that the alcohol industry had abused the extensive bans. Governments improperly relied so much on the alcohol industry to comply and had heavy engagement with big alcohol producers, and this compromised the bans leading to unnecessary delays.

The media was at times in support of the big alcohol industry and branded the ban as a prohibition approach that undermines business and denial of access to low-income earners. The media argued that the truth is that consumers were usually aware of the risks and benefits associated with products they use before consumption. The alcohol manufactures have paid for media space to argue, for example in Nigeria, that the ban on alcohol in sachets and small plastic bottles could create more hurdles for the manufacturers in that segment of the market. On a number of occasions, they have demanded through the press that they be given more time to allow them to migrate to big packaging options/ alternatives. It was also noted that more businesses have been forced to rebrand products and services into smaller packages (sachetisation) to boost profitability by targeting low-income earners.

The ban also led to a shift or migration to packing alcohol from polythene bags to plastic bottles with a minimum of 200mls. After the ban and setting a minimum limit of 200mls, new entrants entered the production and packing of alcohol in small quantities. Prices went down and consumption spiked. In all countries where bans were instituted the was a delay in transiting or migrating to plastic bottle packaging and the volume largely remains at 200 mls, almost the same price of the banned packages. We failed to see the impact of the change in package and the price dropped again. Access and pricing with an increase in taxation need to move together.

The ban of minimal packaging of alcohol in sachets could be easily implemented with laws of weights and measures which provides a minimum standard and eliminate small amounts of certain products. Availability and access in the long run are not affected and the negative attitude was difficult to measure as result of the ban. We need to explore all means that help reduce exposure of alcohol to young people buy eliminating small packaging in tot packs and small bottles. The role played by civil society and UN bodies is important too. Alcohol producers were given the leeway to control and apply the ban at their pace. For instance, NAFDAC’s move to ban small packages was made to curtail alcohol abuse in the country following an order given to the Distiller and Blenders Association of Nigeria to embark on intensive nationwide sensitisation campaigns against consumption of alcohol by adolescents below the age of 18 years. Nigeria is picking lessons from the countries that enforced the ban earlier. Rwanda is the only country in Africa 2022 that has banned the packaging of alcoholic drinks in plastic bottles. It alleges that that has been proven to be harmful to consumers’ health. And yet there are affordable alternatives, and all have to use glass bottles.

Greenpeace Africa campaigns in Senegal against single-use plastics, recalling the need to extend the implementation of the 2015 law against small plastic bags, until a complete ban on singleuse plastics is achieved. Following February’s decision of Senegal’s Minister of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Abdou Karim Sall, to ban water sachets and single use plastic cups, 15 ministers for environmental protection from ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) have also agreed to ban the import, production and marketing of plastic packaging in the region by 2025 [8-21].

Conclusion

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Over 10 African governments banned alcohol packed in sachets and tot packs. Most African countries failed to show a decline in alcohol availability, accessibility and acceptability decline amongst young people as a result of alcohol sachet ban but also there is still resistance from the manufacturers who are looking at the profits vs the health-related costs. Alcohol packed by the informal sector doesn’t meet the standard and it was noted that alcohol was lethal and had negative health and social consequences. Did the ban address the alcohol content (ABV) or was it more concerned about the size of packaging, assuming access will be limited amongst the youth and low-income adults?

The interest of the ban was increased taxation revenue and eliminating the small packages given the revenue authority’s difficulty in tracking them using their digital systems. A case in Uganda, however, shows that it is taking concrete steps towards more effectively regulating liquor in order to bring every alcohol product into the taxation curve. The enforcement of the ban varied depending on issued the ban, availability of human resource and cooperation of the community and heightened awareness about the sachet package. The intended benefits of the ban regarding access and availability appeared to work well in short term, more in the city as compared to rural areas. Availability and access in the long run are not affected as brewers used plastic bottles to pack same amount of alcohol and new players entered the market. We noted that eight years later, in Cameroon’s capital Yaoundé and the economic capital Douala, brightly coloured packs of sachets of Bullet, Fighter, Shoot and Shooter seem to be everywhere and appeared on market, this problem appeared in all countries that banned small sachets.

FOOT NOTES

2https://africatimes.com/2020/09/28/south-africas-economic-recovery-complicated-by-costs-of-prohibition/

Recommendations

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

We need to explore all means that help reduce exposure of alcohol to young people buy eliminating small packaging in tot packs of 200mls to 300mls and small plastic bottles and eliminate singleuse plastic. The ban on minimal packaging of alcohol in sachets could be easily implemented with laws of weights and measures which provides a minimum standard and eliminate small amounts of certain products. A multi-disciplinary approach is needed from ministries of health, trade and local government and police in enforcement of the ban and addressing back-door production. We need to be appreciating the role played by civil society and UN bodies to increase awareness. Single-use plastic used for packaging water or alcohol be banned completely and the use of glass adopted as Senegal and Rwanda have done. Local manufacturing companies should be monitored to ensure that they do not produce, and pack illegal substances and bans are enforced to the dot. Taxation laws: Revision of laws by tagging taxes to each alcohol unit each bottle contains. This will increase the prices of alcohol and in turn reduce the rates of production and consumption of alcohol.

Acknowledgement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

None.

Conflict of Interest

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

No conflict of interest.

References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Problem and the Dangers of Packing Alcohol in Small Quantities

- Methodology

- Results

- Big Brewers Versus Small-Scale Distillers and Illicit Alcohol; A Case for Uganda

- Challenges in Enforcing Bans

- Adherence and Conflict of Interest by the Alcohol Industry

- Challenges and Setbacks in Enforcement

- Resurgence of alcohol sachets in Zambia and Uganda 2022

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

- Monica Swahn, Rachel Culbreth, Cherell Cottrell-Daniels, Nazarius M Tumwesigye, David Jernigan, et al., (2022) social norms regarding alcohol use, perceptions of alcohol advertisement and intent to drink alcohol among youth in Uganda. International journal of health promotion and education.

- Connor JP, W Hall (2015) Alcohol Burden in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. The Lancet 386 (10007): 1922–1924.

- Casswell S, T Thamarangsi (2009) Reducing Harm from Alcohol: Call to Action. The Lancet 373 (9682): 2247–2257.

- https://movendi.ngo/news/2022/01/14/australia-brings-back-alcohol-sachets-as-african-countries-get-rid-of-harmful-packaging/.

- Arasi O, Ajuwon A (2020) Use of sachet alcohol and sexual behaviour among adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. Mar;20(1):14-27.

- Swahn MH, Buchongo P, Kasirye R (2018) Risky behaviors of youth living in the slums of Kampala: a closer examination of youth participating in Vocational Skills programs.

- http://www.add-resources.org/liqour-sachets-banned-in-zambia.5043749-79090.html.

- https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/south-africa-south-africa-lifts-fourth-prohibition-domestic-transportation-and-sale-liquor.

- https://businessday.ng/news/article/sachet-alcohol-ban-to-trigger-more-hurdles-for-manufacturers-analysts/.

- https://www.africanews.com/2022/11/11/cameroon-despite-a-ban-whisky-sachets-remain-very-popular//.

- https://www.africanews.com/2017/03/01/tanzania-bans-alcohol-in-sachets-to-protect-the-youth-and-environment/.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/24544467@N02/32759908337.

- https://allafrica.com/stories/201205141146.html

- https://allafrica.com/stories/201205080266.html

- http://www.hrc.org.zm/index.php/multi-media/news/185-hrc-welcomes-government-ban-of-tujilijili-alcohol-sachets

- http://www.daily-mail.co.zm/get-rid-of-tujilijili-again/

- Mieka Smart, Hilbert Mendoza, Aloysius Mutebi, Adam J Milam, Nazarius Mbona Tumwesigye (2021) Impact of the Sachet Alcohol Ban on Alcohol Availability in Uganda. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 82(4):511-515.

- https://www.independent.co.ug/mark-ocitti-support-government-ban-alcohol-sold-sachets/

- https://movendi.ngo/news/2019/05/14/uganda-11-companies-not-complying-with-sachet-alcohol-ban/

- Swahn MH, Culbreth ER, Staton AC, Self-Brown RS, Kasirye R (2017) Alcohol-Related Physical Abuse of children in the slums of Kampala Uganda.

- Swahn MH, Culbreth ER, Tumwesigye MN, Fodeman A, Kasirye R, et al., (2022) Heavy drinking and problem drinking among youth in Uganda: A structured equation model of alcohol marketing, advertisement, perceptions and social norms.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...