Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Case Report(ISSN: 2641-1709)

The Discrepancy Between the Length of the Styloid Process and the Symptoms of Eagle’s Syndrome: A Case Report Volume 4 - Issue 1

Nguyen Nguyen1,2, Thanh Phu Nguyen3 and Kyu Sung Kim1,2*

- 1Research Institute for Aerospace and Medicine, Inha University, Incheon, Korea

- 2Department of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surg, Inha University Hospital, Korea

- 3Department of Otolaryngology, Khanh Hoa General hospital, Vietnam

Received: February 12, 2020; Published:February 24, 2020

Corresponding author: Kyu Sung Kim, Department of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, Inha University Hospital, Incheon, Korea

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2020.04.000178

Abstract

Eagle’s syndrome was a rare condition, and it was not commonly suspected in clinical practice. The elongation of the styloid process (SP) was considered as the main cause of this syndrome. However, many patients who were incidentally found of an elongated SP were asymptomatic. This case report presented a rare case of the bilateral elongated SP with the unilateral symptom. A 59-year-old woman who had come to our attention with the complaint of pain in the right side of the neck, and intensified pain during neck rotation, swallowing and mouth opening. She also complained of pain in the angle of the mandible, the face and otalgia. The computed tomography scans and 3D reconstruction allow us to measure the angulation and length of the SP as well as evaluate the relationship between the SP and adjacent anatomical structures. Surgical excision was performed on the right side although the patient was diagnosed with bilateral elongated SP. The postoperative course passed regularly, and the postsurgical control showed no complaint.

Keywords: Eagle’s Syndrome; elongated styloid process; stylohyoid complex

Introduction

The styloid process (SP) is a projection of thin, cylindrical and along bone from the temporal bone, and its location is between the internal and external carotid artery. The mastoid process and the tonsillar fossa are at the posterior and inside it, respectively [1]. The styloid process is one part of the stylohyoid complex including stylohyoid ligament, lesser horn of hyoid bone [2]. Initially, elongated SP syndrome or Eagle’s syndrome was described by an otorhinolaryngologists, Dr. Watt Eagle [3]. The symptoms have diversely presented with ipsilateral cervicofacial pain, referred otalgia, sore throat, dysphasia, headache, and a foreign body sensation in the pharynx. The pain regularly limits in the angle of the mandible, and neck mobility will be reduced when the head rotates to the affected side [1,4]. A physical examination is induced by digital palpation of elongated SP through the tonsillar fossa, and once palpated, the symptoms may intensify. The diagnosis is often misleading because of the vagueness of symptoms as well as the infrequent clinical observation, and these patients seek a variety of treatments in several different clinics such as dentistry, neurosurgery, neurology, psychiatry. These treatments do not relieve the symptoms, and they make the whole clinical picture cloud [4,5]. The mean length of the styloid process ranged from 20 to 25 mm [6,7]. Generally, the SP is considered elongation when it is beyond 30 mm [6,8]. There are two types of this syndrome: the classic and the carotid artery type. The former type, also known as stylalgia, always following tonsillectomy, and usually related to the elongated SP. The latter type is characterized by nonspecific symptoms that are caused by compression of the sympathetic fibers and carotid arteries, and the most common etiology of the syndrome that is the mineralization of the stylohyoid ligament [7,9]. Eagle’s syndrome is caused by an elongated SP, on the contrary, the presence of an abnormal length of SP does not result in Eagle syndrome. Here, we present a case with unilateral Eagle syndrome and bilateral elongation of the SP

Case Report

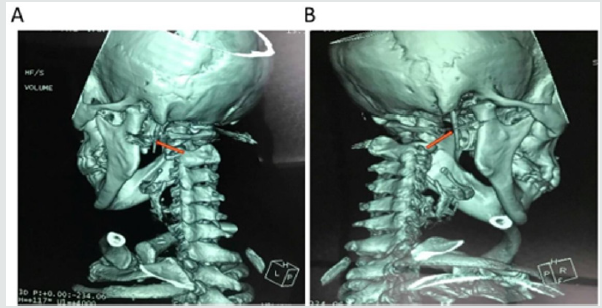

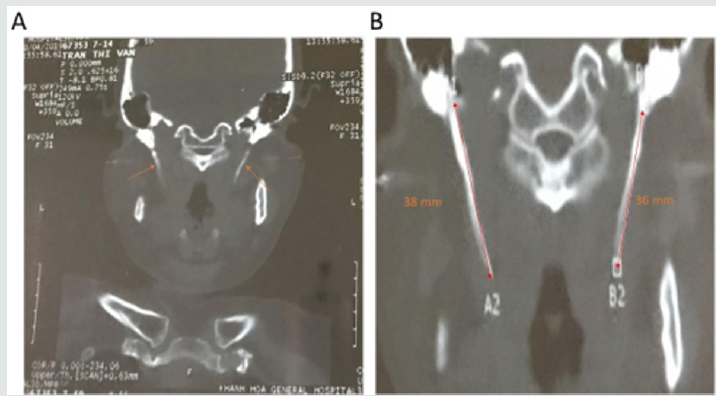

A 59-year-old woman presented to the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Khanh Hoa general hospital, Viet Nam with the complaint of pain in the right side of the neck, the angle of the mandible, the face and otalgia that had started approximately one month previously. She simultaneously complained of intensified pain during neck rotation to the right side, swallowing and mouth opening. The patient was uneventful for any surgical or trauma history. In the physical examination, the pain was felt when palpation was performed at the angle of mandible, sternomastoid muscles. Intraoral examination, the SP was not felt on palpation of the tonsillar fossa. No particular abnormalities were detected in the video-laryngoscopic examination and neck ultrasound. Finally, the symptoms did not improve following medical therapy. Thus, the patient underwent a CT scan with the 3D reconstruction of the head and neck (Figure 1). The CT examination revealed a bilateral elongation of the SPs. The SPs were measured 36 mm on the right side and 38 mm on the left side (Figure 2). Lidocaine (2%) was deeply infiltrated into the lateral tonsillar fossa on the right side. After infiltration, immediate relief of the pain partially supported the diagnosis of Eagle’s syndrome. Although the SP on the left side was longer than another on the right side, we decided to do a right styloidectomy because of no symptom revealing on the left side. The styloidectomy was made via the intraoral surgical approach (Figure 3). Antibiotic was administered preoperatively. The surgery was under general anesthesia and the postoperative period passed regularly. The patient was discharged on the second postoperative day. At regular postoperative examinations, complete remission of symptoms was accomplished.

Figure 1: Computed tomography scan with 3D reconstruction on the left (A) and right (B) side that showed an elongation of the SPs (orange arrows).

Figure 2: A 59-year-old woman reported neck pain on right side of the face during neck rotation to right side and while swallowing and opening her mouth. CT examination showed the bilateral elongation of the SPs (A), which was long elongated on the left than on the right side (B). The SPs measured 38 and 36 mm on the left and right side, respectively (B).

Figure 3: Intraoral approach to the styloid process. Tonsillectomy was performed first on the right side. The palpation of the tonsillar bed was performed, and the tip of the right SP was identified. The mucosa was dissected longitudinally at the point of the felt tip in the tonsillar fossa. To avoid vascular injury, the parapharyngeal space was carefully dissected by q-tips. Palpation was occasionally performed during surgery to identify the location of the SP. After the SP was exposure and excised, the tonsillar bed was carefully sutured with absorbable sutures.

Discussion

The stylohyoid complex (SC) was formed by the SP, stylohyoid ligament, lesser cornea of the hyoid and superior portion of the hyoid corpus. Embryologically, these have been derived from Reicher’s cartilage (the second branchial arch) [6,10]. Based on the successive development of the SC, it could be divided into four sections. The most proximal SC was known as the tympanohyaland which gave rise to the tympanic portion of the SP. The second portion, known as the stylohyal, forming the distal portion of the SP. The third portion (the ceratohyal) degenerated in utero, and it gave rise to the stylohyoid ligament. The most distal portion, known as the hypohyal, forming the lesser cornu of the hyoid bone [10]. The SP originated from the temporal bone behind the mastoid, and it ran anteromedially. Its anatomical variation was rarely changed in course, and it passed between the external and internal branches of the carotid artery. Cranial nerves including n. accessory, n. hypoglossus, n. vagus and n. glossopharingeus were placed medially to the SP. Three muscles (stylopharyngeus, stylohyoid and styloglossus) and two ligaments (stylohyoid and stylomandibular) were attached on the SP [2,5,10]. The length of the SP was individually variable, and the SP was considered as the elongation whenever it was longer than 30 mm. However, the existence of an elongated SP was not pathognomonic for Eagle’s syndrome, because many patients who were found of an elongated SP were asymptomatic [10]. Moreover, the elongation of the SP occurred in approximately 4% of the population [11], and only 4% of this group complained of symptoms [1,12]. Several pathophysiological mechanisms were used to explain the symptoms of Eagle’s symptoms:

a) The proliferation of granulation tissue after traumatic fracture of the SP induced the pressure on the surrounding structure [13,14].

b) Compression of adjacent nerves such as the

glossopharyngeal nerve, the trigeminal nerve and the chorda

tympani nerve [1].

c) Insertion tendonitis was known as a degenerative and

inflammatory change which occurred in the tendinous portion

of the connected area of the stylohyoid ligament [1,14].

d) The formation of granular tissue after tonsillectomy or the

direct compression resulted in the irritation of the pharyngeal

mucosa (involvement of the 5, 8, 9, and 10 cranial nerves) [1].

e) The impingement of the sympathetic nerve in the arterial

sheath [15].

Treatment of Eagle’s syndrome was both conservative and surgical. The conservative treatment included nonsteroidal or steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, anticonvulsants and exercises for the neck [1,7]. The surgical method involved amputating or removing the elongated SP via the intraoral or extraoral approach. Both approaches have been known to have pros and cons in use. The intraoral technique was simpler and took less time as well as avoided the surgical scar; however, its disadvantages were injury of the blood vessels, infection of deep neck spaces and poor visualization of the surgical field. On the other hand, the extraoral technique through cervical incision allowed better visualization of the operative field. This technique, nevertheless, took a longer time, and it could cause injury of the facial nerve. Moreover, the patient postoperatively recovery was longer and resulted in a visible scar [16-18]. Routinely, we took the intraoral approach to our patients. Due to being familiar with the technique, we have not encountered any of the complications which were mentioned above. Also, the injury of vascular and neural tissues was minimal by this method.

Conclusion

The case verifies the possibility that unilateral symptoms can occur in the bilateral elongation of the styloid process. To avoid excessive resection, the side of the styloid process should be selected by the accurate history of the patient, the tonsillar palpation and radiologic confirmation.

Conflicts of interest

Authors have none to declare

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2018R1A6A1A03025523).

References

- Han MK, Kim DW, Yang JY (2013) Non-Surgical Treatment of Eagle's Syndrome - A Case Report. The Korean journal of pain 26(2): 169-172.

- Chalkoo A, Makroo N, Peerzada G (2015) Eagle's syndrome: Report of two cases. Journal of Indian Academy of Oral Medicine and Radiology 27(4): 612-615.

- Eagle WW (1937) Elonggated styloid processes: Report of two cases. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 25(5): 584-587.

- Chrcanovic BR, Custódio ALN, De Oliveira DRF (2009) An intraoral surgical approach to the styloid process in Eagle’s syndrome. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 13(3): 145-151.

- More CB, Asrani MK (2011) Eagle's Syndrome: Report of Three Cases. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery: official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India 63(4): 396-399.

- Balcioglu H, Kilic C, Akyol M, Ozan H, Kokten G (2009) Length of the styloid process and anatomical implications for Eagle's syndrome. Folia morphologica 68: 265-270.

- Taheri A, FirouziMarani S, Khoshbin M (2014) Nonsurgical treatment of stylohyoid (Eagle) syndrome: a case report. Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons 40(5): 246-249.

- Murtagh RD, Caracciolo JT, Fernandez G (2001) CT Findings Associated with Eagle Syndrome. American Journal of Neuroradiology 22(7): 1401-1402.

- Shahoon H, Kianbakht C (2008) Symptomatic Elongated Styloid Process or Eagle's Syndrome: A Case Report. Journal of dental research, dental clinics, dental prospects 2(3): 102-105.

- Scavone G, Caltabiano DC, Raciti MV, Calcagno MC, Pennisi M, et al. (2018) Eagle's syndrome: a case report and CT pictorial review. Radiology case reports 14(2): 141-145.

- Okabe S, Morimoto Y, Ansai T, Yamada K, Tanaka T, et al. (2006) Clinical significance and variation of the advanced calcified stylohyoid complex detected by panoramic radiographs among 80-year-old subjects. Dento maxillofacial Radiology 35(3): 191-199.

- Rechtweg JS, Wax MK (1998) Eagle's syndrome: A review. American Journal of Otolaryngology 19(5): 316-321.

- Blythe JNSJ, Matthews NS, Connor S (2009) Eagle's syndrome after fracture of the elongated styloid process. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 47(3): 233-235.

- Kiralj A, Ilic M, Pejakovic B, Markov B, Mijatov S, Mijatov I (2015) Eagle's syndrome - A report of two cases. Vojnosanitetskipregled 72: 458-462.

- Diamond LH, Cottrell DA, Hunter MJ, Papageorge M (2001) Eagle's syndrome: A report of 4 patients treated using a modified extraoral approach. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 59(12): 1420-1426.

- Shilpa H, Mathew AS, Hemraj S, Sridhar A (2018) Endoscopic transoral resection of an elongated styloid process: a case report. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 4(5): 4.

- Matsumoto F, Kase K, Kasai M, Komatsu H, Okizaki T, Ikeda K (2012) Endoscopy-assisted transoral resection of the styloid process in Eagle's syndrome. Case report. Head & Face Medicine 8(1): 21.

- Yavuz H, Caylakli F, Erkan A, Ozluoglu L (2011) Modified intraoral approach for removal of an elongated styloid process. Journal of otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery 40(1): 86-90.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...