Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Mini Review(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Partial Glossectomy for Treatment of Macroglossia Secondary to Myeloma-Associated Amyloidosis: A Case Report Volume 7 - Issue 5

Chong Kim1, Jeffrey N James2, Rafik Abdelsayed3, Caroline Glessner1, Kyle B Frazier4 and Andrew C Jenzer6*

- 1Dental Student, Dental College of Georgia, Augusta University, Georgia

- 2Program Director and Associate Professor, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Augusta University, Georgia

- 3Professor, Department of Oral Biology and Diagnostic Sciences, Augusta University, Georgia

- 4Resident, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Augusta University, Georgia

- 5Associate Professor, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Augusta University, Georgia

Received: December 06, 2021; Published: December 14, 2021

Corresponding author: Andrew C Jenzer, Associate Professor, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Augusta University, Georgia

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2021.07.000273

Abstract

Around 10-15% of patients with multiple myeloma develop amyloidosis due to the extracellular deposition of light-chain amyloid molecules. When this deposition occurs in the tongue, patients may exhibit macroglossia. The sequelae of this macroglossia can include dysphagia and gagging, tooth displacement, and airway compromise. This article presents the case of a 43-year-old African American female who was treated with a partial glossectomy secondary to amyloidosis related multiple myeloma.

Introduction

Macroglossia is the abnormal enlargement of the tongue with significant disproportionate appearance to other structures in the mouth. Macroglossia may be categorized as either primary (i.e., muscular enlargement) or secondary. Secondary macroglossia is related to, or associated with, neoplastic processes, metabolic or endocrine disorders, or syndromic conditions [1-4]. Examples of underlying disease processes causing secondary macroglossia are vascular malformations (such as hemangioma or lymphangioma) and myxedema due to hypothyroidism [1,3]. Macroglossia can also occur secondary to amyloidosis [5]. The intent of this article is to report on the case of a 43-year-old female who presented with enlarged, firm, and scalloped tongue secondary to amyloidosis related to multiple myeloma.

Case Description

A 43-year-old African American female presented to the

Augusta University Medical Center due to dysphagia and gagging.

She had been diagnosed with multiple myeloma one month earlier

at an outside hospital. At that time, she noted weight loss of 40

pounds over the previous four months. Computed tomography (CT)

scan showed lytic lesions of the spine, ribs, and sternum. Myeloma

workup was performed, and patient was diagnosed with Revised

International Staging System (R-ISS) stage 2 multiple myeloma. She

was discharged to home in stable condition. The patient’s treatment

plan was to receive Velcade, Revlimid, and dexamethasone (VRD)

therapy, which she started shortly thereafter. Upon presentation at

the Augusta University Medical Center, the Otolaryngology service

was consulted regarding her complaint of dysphagia and gagging,

which she had been experiencing in the months leading up to

her diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Otolaryngology performed

a transnasal flexible laryngoscopy that showed no structural

abnormalities of the base of tongue or supraglottic structures.

Gastroenterology was consulted and performed an

esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which only showed moderate

to severe antral gastritis. Additionally, a percutaneous endoscopic

gastrostomy (PEG) was performed during that procedure to ensure

the patient received proper nutritional intake, as her ability to

tolerate food by mouth was impaired secondary to the dysphagia

and gagging. The patient also had a modified barium swallow study,

and no aspiration or penetration was observed. The only potential

etiology of the dysphagia and gagging noted was an enlarged

tongue. The oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMS) service was consulted to determine if surgical management of the macroglossia

was appropriate. Intraoral examination showed macroglossia with

scalloping in the anterior and lateral borders of the tongue (Figure

1). Amyloidosis of the tongue secondary to multiple myeloma was

suspected. The patient had previously had bone marrow aspirate and

abdominal fat pad biopsy that were both negative for amyloidosis.

OMS performed a partial glossectomy via keyhole technique

with submission of excised tissue in 10% buffered formalin for

pathological examination, which confirmed amyloidosis. Following

the procedure, the patient remained intubated in the surgical

intensive care unit (SICU). She was extubated on post-operative day

#2 without the need for tracheostomy.

The patient had post-operative edema of the tongue, and thus still had dysphagia after surgery; however, this resolved over the next few months, and her dysphagia had significantly improved compared to her pre-operative state. Revlimid was discontinued prior to surgery to mitigate risks of complications with healing. In place of VRD therapy, she was switched to cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone (CyBorD) therapy shortly after surgery. A cardiac MRI was subsequently performed and did not show signs of cardiac involvement of amyloidosis. The patient’s PEG tube was removed five months after partial glossectomy after she demonstrated the ability to swallow solid foods by mouth. One year after surgery, she stated that her swallowing had significantly improved prior to the partial glossectomy. She did note some alterations in taste and intermittent lingual paresthesia, but these were not major complaints. Her oncologist noted very good response to CyBorD therapy, and the patient underwent an autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant 13 months after her partial glossectomy.

Pathologic Findings

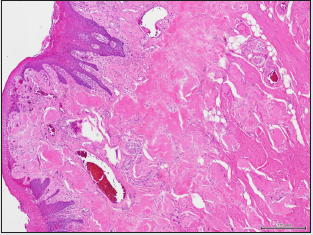

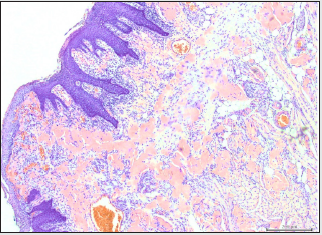

Microscopic examination of formalin-fixed paraffinembedded 5μ thick sections revealed tongue mucosa covered by parakeratinized squamous mucosa which supports subepithelial diffuse amorphous eosinophilic deposits. The amorphous deposits were markedly eosinophilic, largely acellular and afibrillar. The material deposition is noted in the superficial and deep lamina propria and in perivascular and intramuscular areas (Figure 2A). Sections stained with Congo red showed positive reddish deposits with the stain confirming the diagnosis of amyloid deposition (Figure 2B). The Congo red-stained deposits demonstrated characteristic apple-green birefringence when viewed under polarized light.

Figure 2A: Photomicrograph of tongue biopsy showing subepithelial stromal exctracellular amorphous eosinophilic amyloid deposition (hematoxylin and eosin-stained; original magnification X100).

Figure 2B: Photomicrograph of Cong red-stained sections showing red amyloid deposits in the extracellular, perivascular and intramuscular zones (Congo red-stained; original magnification X100).

Discussion

Macroglossia can arise from many different etiologies,

including amyloidosis. Amyloidosis is a group of diseases that share

the feature of the deposition of an extracellular proteinaceous

substance referred to as amyloid [6]. Approximately 39% of

patients with amyloidosis exhibit oral manifestations, with the

tongue being the most common site [7,8]. There are multiple

classification systems for amyloidosis. Broadly, amyloidosis can be

categorized as either localized or systemic [8]. The systemic type

can be classified at least into primary, secondary, and hereditary,

with some authors suggesting additional categories, such as for

cases associated with multiple myeloma [8]. Other authors group

amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma into the primary or

secondary categories [9-11]. Multiple myeloma is a monoclonal,

multicentric neoplastic proliferation of bone marrow-based B

lymphocytes which differentiate into plasma cells [12]. Myeloma

cells produce various proteins, most frequently M protein in the

form of IgG (60%), followed by IgA (20%-25%); only rarely are IgM,

IgD, or IgE M protein observed. In few other cases, myeloma cells

produce only κ or λ light chains. These light chains are small and

can be excreted in urine where they are referred to as Bence-Jones

proteins.

Males, African Americans, and adults between 60 and

70 years of age are most affected by this condition [9]. The

malignancy results in an uncontrolled proliferation of atypical and

nonfunctional immunoglobulins [13]. The solitary plasmacytoma

is also a monoclonal neoplastic proliferation of plasma cells,

but unlike multiple myeloma, only a single mass is present.

Plasmacytomas can arise either in bone or in soft tissues. Most

patients with plasmacytoma of bone will ultimately develop

multiple myeloma when observed on a long-term basis [9,14].

Clinically, patients with multiple myeloma present with bone pain,

anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, metastatic calcifications,

renal failure, and Bence-Jones proteins in urine [15]. These

patients are more susceptible to infections due to the reduced

number of functional immunoglobulins and leukopenia. If there

is maxillofacial involvement, osteolytic “punched out” radiolucent

lesions may be seen on radiographs affecting the jaw bones. Tumorlike

yellowish nodules may be found in the oral mucosa. Salivary

glands may also be affected [16]. In about 10-15% of patients with

multiple myeloma, the accumulation of the abnormal light chain

proteins results in amyloidosis in the oral mucosa, and may present

as macroglossia [9,16]. The reported prevalence of amyloidosisassociated

macroglossia secondary to multiple myeloma varies,

but it has been suggested to be up to 40% [9,17]. Macroglossia

from this condition can become severe enough to splay teeth,

affect speech and swallowing, and cause airway obstruction,

sometime necessitating a tracheostomy [11]. Medical history,

clinical findings, biopsy, and histological exam of amyloid lesions

are all key components of determining the underlying cause of

macroglossia and best treatment plan. While this condition leads

to both functional and cosmetic problems for patients, there are

no formal guidelines for the treatment of macroglossia secondary

to amyloidosis [18,19]. In this case, a partial glossectomy was

performed and tissue was submitted to confirm the macroglossia

was a complication of amyloidosis associated with multiple

myeloma. The patient had improvement of her symptoms starting

around 5 months after surgery, and the improvement was sustained

through one year after surgery.

This case, as well as others presented in the literature,

document successful surgical intervention for macroglossia

associated with amyloidosis and its complications [18]. However,

it must be noted that macroglossia is likely to recur if the systemic

disease process leading to amyloid deposition is not medically

controlled. Thus, it is necessary to judge each case based on

multiple criteria, including the severity of symptoms (airway

compromise, nutritional compromise) and likely of recurrence (i.e.,

whether medical management can suppress further deposition

of amyloid). The major shortcoming of this report is the lack of

volumetric data prior to, and after, surgery. This would have given

an objective measure of the amount of reduction achieved through

the partial glossectomy, as well as the volumetric stability of the

tongue over time. Nonetheless, the patient’s improvement in swallowing and the ability to remove her PEG tube are certainly

markers of successful treatment. In conclusion, although there is no

consensus in the literature regarding the surgical management of

macroglossia due to myeloma-associated amyloidosis, the authors

of this paper suggest, as have others, that partial glossectomy for

the treatment of symptomatic macroglossia caused by myelomaassociated

amyloidosis is a reasonable treatment option [20].

References

- Nambiar BC, Prabhakar T, Manrai KP, Rawat GS (2001) Macroglossia: A Rare Clinical Entity. Medical journal, Armed Forces India 57(2): 169-171.

- Kadouch M (2012) Surgical treatment of macroglossia in patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: a 20-year experience and review of the literature. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 41(3): 300-308.

- Melville, James C (2018) Unusual Case of a Massive Macroglossia Secondary to Myxedema: A Case Report and Literature Review. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 76(1): 119-127.

- Guimaraes CVA, Donnelly LF, Shott SR (2008) Relative rather than absolute macroglossia in patients with Down syndrome: implications for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatr Radiol 38: 1062.

- Maturana-Ramírez A (2018) Macroglossia, the First Manifestation of Systemic Amyloidosis Associated with Multiple Myeloma: Case Report. Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 119(6): 514-517.

- da Costa KVT, Ribeiro CMB, de Carvalho Ferreira D (2018) Dysphagia due to macroglossia in a patient with amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma: A case report. Spec Care Dentist 38: 255-258.

- Penner Carla, Muller Susan (2006) Head and neck amyloidosis: A clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Oral oncology p. 42.

- Xavier SD, Filho IB, Müller H (2005) Macroglossia Secondary to Systemic Amyloidosis: Case Report and Literature Review. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal 84(6): 358-361.

- Neville Brad W (2016) Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Fourth ed. Elsevier pp. 563-566.

- Falk R, Comenzo R, Skinner M (1997) The systemic amyloidosis. New England Journal of Medicine 337: 898-909.

- Marx RE, Stern D (2012) Oral and maxillofacial pathology: a rationale for diagnosis and treatment. Hanover Park, IL: Quintessence.

- Shibata Masami, Kodani Isamu, Doi Rieko, Takubo Kazuko, Kidani Kazunori, et al. (2003) Multiple Myeloma Presenting Symptoms in the Oral and Maxillofacial Region Yonago Acta Medica p. 46.

- Pecoraro Valentina (2015) The Prognostic Role of Bone Turnover Markers in Multiple Myeloma Patients: The Impact of Their Assay. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 96(1): 54-66.

- Caers J, Paiva B, Zamagni E (2018) Diagnosis, treatment, and response assessment in solitary plasmacytoma: updated recommendations from a European Expert Panel. J Hematol Oncol 11: 10.

- Riccardi, Alberto (1991) Changing Clinical Presentation of Multiple Myeloma. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology 27(11): 1401-1405.

- Ariyaratnam S, Sweet C, Duxbury J (2005) Low grade multiple myeloma that presented as a labial swelling- A case report. Br Dent J 199: 433-435.

- Hicks KA, Dickie WR (1973) Amyloidosis: report of a case presenting with macroglossia. Br J Plast Surg 26: 274-276.

- Gadiwalla Y, Burnham R, Warfield A, Praveen P (2016) Surgical management of macroglossia secondary to amyloidosis. BMJ case reports.

- Shahbaz A, Aziz K, Umair M, Malik ZR, Awan SI (2018) Amyloidosis Presenting with Macroglossia. Cureus 10(8): e3185.

- Guijarro-Martinez (2009) Rational management of macroglossia due to acquired systemic amyloidosis: does surgery play a role? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 67(9): 2013-2017.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...