Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Parental Perspective Pre- and Post-Cochlear Implantation in Tanzania Volume 3 - Issue 2

Rashida Muslim Hassuji*

- Audiologist and Speech Language Pathologist, Hear Well Audiology Clinic, Tanzania

Received:September 28, 2019; Published:October 04, 2019

Corresponding author: Rashida Muslim Hassuji, Audiologist and Speech Language Pathologist, Hear Well Audiology Clinic, Tanzania

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2019.03.000156

Abstract

Background: The National Cochlear implant program in Tanzania was established in the year 2017. Prior to this, very few children with Profound Sensorineural Hearing Loss benefited from this surgery abroad through grants from the Ministry of Health. Since the establishment of the local program, there is an increased awareness amongst parents’, and many are seeking to benefit from this initiative. The challenge, however, remains the measurements of expectations of the parents and the actual outcomes after the surgery. This is mainly due to the perspective of the parents which comes about from their understanding of the whole process of surgery and the rehabilitation after surgery that determines expected outcomes.

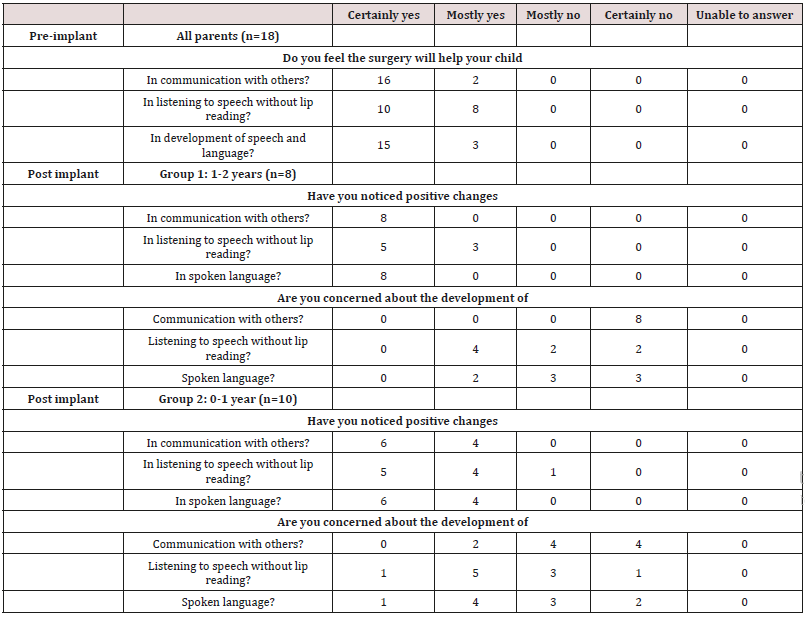

Aim: This study aims to establish a direct link between the parental perspective pre and post cochlear implant surgery. Participants: A total of 18 children between ages of 3 years and 6 years, divided in two groups, G1=children who have been implanted for 1-2 years (n=8) and G2=children who have been implanted for 0-1 years (n=10).

Method: A non-standardized closed ended questionnaire with questions on perspectives of three domains i.e. Communication, Listening Skills and Speech and Language development was administered to the parents, pre-implantation and 1year post implantation for G1 and 6 months post-implantation for G2.

Results: In all of the 18 cases, pre-implantation expectations were higher than the actual perspectives post-implantation. However, G1 parents had higher scores than G2 i.e. The preimplantation expectations were somehow met after 1 year of implantation.

Conclusion: The study demonstrates the ability of Cochlear Implantation to meet the parental expectations in the 3 outcome domains i.e. communication, listening skills and the development of speech and language. However, this is subject to the time frame post implantation i.e. the longer the time, the better the pre-implant perspectives are met.

Introduction

Cochlear implants, as prosthetic devices designed to replace the function of the inner ear, have become a widely used intervention method for people with severe to profound sensorineural hearing losses who gain little or no benefit from conventional hearing aids. Since their approval by the United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in 1990 for children as young as the age of two [1], pediatric cochlear implantation has become an increasingly routine procedure in numerous countries worldwide as a management option for permanent childhood hearing loss. The foundation of cochlear implant programs for these patients began in developed countries and over time the devices, surgical methods, and rehabilitation programs improved, which thus led to their initiation in developing countries. Prior to the commencement of locally performed cochlear implant surgeries in Tanzania, candidates for implantation had to travel to other countries for the procedure. This was a costly and intensive process for privately and government funded patients alike, a factor that fueled the need for a local program. In 2017, six children were implanted for the first time at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and to date a total of thirty patients have been implanted altogether. Over the time, since the first surgeries, local professionals and rehabilitation centers have become more proficient in evaluating and caring for these patients, and an increased awareness of hearing impairments as a whole has been observed. Perceptions regarding cochlear implants of health professionals, the general public, and in particular parents of implantees and potential candidates have also been seen to change, becoming more informed and understanding. Candidacy for cochlear implants is assessed on a case-by-case basis, with referrals for assessment primarily made according to candidacy criteria set out by the Cochlear Implant Group Tanzania [2].

Currently, the indications for cochlear implantation from an audiological perspective are as follows; bilateral severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss (typically >90dBHL at 2kHz and onwards), limited benefit from hearing aids, and the absence of contraindications for implantation. The candidates undergo thorough examinations by audiologists, speech-language pathologists, radiologists, otorhinolaryngologists, pediatricians, social services, psychologists, and other professionals where necessary. This process is not unlike guidelines in other countries with cochlear implant programs, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom make similar recommendations, although in 2018 with suggestions from the British Cochlear Implant Group (BCIG) updated the eligibility criteria to define severe to profound deafness as only hearing sounds greater or equal to 80dBHL at two or more frequencies between 500Hz and 4kHz [3]. These recommendations and procedures differ slightly between countries and programs and may also change depending on whether the candidate is privately or publicly funded. Outcomes for pediatric cochlear implantation worldwide have encouraged their use as an intervention method for hearing impairments, reinforced by their widespread success and relatively low rate of complication [4]. A prospective longitudinal study of spoken language development in children implanted before the age of five, conducted over a period of three years, revealed significant improvements in spoken language performance (comprehension and expression) particularly over the first three years of device use. Greater improvements were seen in younger children and children with more residual hearing prior to implantation, although in all children outcomes surpassed the improvements predicted by their pre-implant assessment baseline scores [5]. A retrospective study evaluating the outcomes of cochlear implantation in relation to age of implantation conducted by Govaerts et al. [6] studied children with congenital deafness who were implanted before the age of six with a multichannel cochlear implant, evaluating them using Categories of Auditory Performance (CAP) scores and correlating outcomes with age of implantation.

All children demonstrated an increase in scores postimplantation, appearing to benefit from the device. The study identified that implantation between the ages of two and four always resulted in age-appropriate CAP scores after three years of implant usage, while implantation before the age of two years always resulted in immediate normalization of CAP scores. Implantation after the age of four, however, hardly resulted in normal CAP scores, signifying the importance of early intervention in preventing losses of auditory performance following the procedure, and only 20% to 30% of these children were eventually fully integrated into mainstream primary schools [6]. While this study reinforces the significance of age at implantation as a predictor of auditory and language outcomes, it also demonstrates the efficacy of cochlear implants as intervention for pre-lingually deafened children; even in patients implanted later than recommended, significant benefits were observed and a percentage of these patients developed the ability to integrate into mainstream education.

An integral part of the process towards pediatric implantation is continued counselling of parents of patients regarding their child’s impairment, amplification, the device, the surgery, rehabilitation, and of their expectations and outcomes. Parental expectations prior to implantation are considered a key factor in the process of candidacy assessment, so much so that they have been used previously as a criterion in the evaluation of the child’s eligibility for an implant [7]. Without the appropriate counselling and guidance, parents can be led to believe that the implant will work on its own, and that the child will be able to hear and speak shortly after switch-on [8]. Kampfe et al. [7] identified that these expectations can be influenced by the fact that the device is very expensive and high-tech, leading to unreasonable expectations. They also suggest that these expectations can also be partly due to the influence of the media, which presents the implant as an immediate change to hearing – often showcasing only significant reactions of patients in response to sounds [7]. Twenty-six years later, this statement still holds truth, as videos of ‘sensational’ reactions to sounds by implantees are spread on social media and on the news, particularly in countries where programs are in their infancy. These can lead to unrealistic expectations, subsequent stress, and disappointment when their expectations are not met. Families’ stress in relation to cochlear implants has been looked at in numerous studies and is due to a number of sources [9]. One such source is the surgical procedure itself. Although the procedure is quite safe with a low chance of complications [4], it is still a surgical procedure that has its risks, and this results in some anxiety or worry experienced by the parents [9]. It is vital that the procedure is explained appropriately to parents, and sources of clear information about it and the risks it may pose are made easily available. Another source of stress, as previously identified, is the parent’s perceptions when their expectations are not immediately met [10]. Over time this lessens as a stressor particularly as children begin to show improvements. In order to better understand parental expectations, it is important for clinicians to be aware of the reasoning behind their choice in going forward with implantation. A study by Sach & Whynes [11] interviewed 216 parents of children implanted at the Nottingham Pediatric Cochlear Implant Programmes using a mix of structured and open-ended interview formats. When asked about the decision to implant their child, 38% of parents stated that the benefit they expected was ‘improved hearing’, 23% anticipated psychosocial and behavioural benefits, 19% mentioned greater opportunities later in life while 16% cited improvements in speech [12].

In most cases outcomes were reported to be in line with their expectations, and 93% of interviews mentioned ‘improved hearing’ as an outcome of implantation. When interviewed about their expectations, 5% of parents admitted to having high and unrealistic expectations, while 16% mentioned that initial expectations had been low. With its large sample size and extensive data collection, this study has provided an insight into parental perspectives of cochlear implantations and the effect various factors can have on stress, expectations, and outcomes [12]. A study by Hyde et al.

investigating parental expectations and [13] experiences related to their children’s outcomes with implants, surveyed 247 parents in eastern Australia, and compared reports of pre-implant expectations with post-implant outcomes. Findings from this study indicated that while parents had relatively high expectations, these had mostly been met by their children’s outcomes post-implantation. 10% of parents, however, reported that expectations had not been met. Furthermore, the study established that professionals generally did a good job in providing parents with realistic expectations prior to implantation and during rehabilitation [13].

A child’s home and family environment can lead to variations in outcomes seen in implanted children [10,14,15]. Perspectives of parents and guardians towards the device and their children can influence development of the implanted child, as they can affect factors such as the level of support given at home, roles undertaken by family members in therapy, their interactions with the child, and organization and control in homes [14]. Amongst outcome predictors such as duration of deafness and learning style, family structure and support has been identified as a significant predictor of outcome following cochlear implantation as demonstrated by use of the Nottingham children’s implant profile (NChIP) to assess children, family, and support services prior to implantation [16]. Various studies into predictors of spoken language development and good outcomes with cochlear implantation have supported these findings. Better outcomes have been associated with lower ages at implantation [17], early identification of hearing impairment, number of active electrode channels effectively ‘mapped’, and bilateral implantation when compared with unilateral or bimodal stimulation [17]. Boons et al. [17] divide predictors of language development in pediatric cochlear implant recipients into three categories:

a) Auditory factors such as age of implantation or identification,

b) Child-related factors such as the presence of other disabilities and etiology of hearing loss, and

c) Environmental factors such as parental involvement and socioeconomic status.

A retrospective study into these factors involving 288 prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants was conducted through the use of numerous validated outcome measures and standardized questionnaires. The study identified that amongst the factors that can influence outcomes of cochlear implantation, environmental factors related to parental characteristics played an important role. One such factor was the communication mode between parents and their child, as participants were asked whether communication was oral, total (using signs along with spoken language), or bilingual. Another factor looked at whether the parents’ involvement in the rehabilitation process was ‘sufficient’, as it would be in a well-functioning family, or ‘insufficient’ if parents were seen to be unmotivated or unable to fulfill commitments in relation to the child (Table 1).

Boons et al. [17]acknowledge the oversimplification of these classifications and have identified that while it is not a validated measure of parental involvement it can suggest an undesirable attitude of parents towards the child’s impairment and rehabilitation. 96% of parents in this study were seen to be sufficiently involved in their child’s rehabilitation, but in 4% of cases issues were mentioned highlighting insufficient involvement in the process. This factor did not show a significant variation in outcomes in the first two years following implantation, but after a certain amount of time the study identified that the advantages and possible positive effects of a supportive environment become measurable. Multilingualism in communicating with the child also consistently correlated with lower language scores over time and was accompanied by low parental involvement in rehabilitation. These findings suggest that the effects of environmental factors increased as time went on and were more measurable after two years post-implantation [15,17] also reported more significant individual variations in outcomes in children over time and found that levels of parental involvement in the rehabilitation process was associated with children’s linguistic ability four years after implantation [15]. In comparison, higher language achievement in implanted children was associated with parents reporting lengthier and detailed processes in deciding about the implant pre-implantation and who showed a higher level of involvement and commitment with the child’s rehabilitation post-implantation [15]. This correlation was also identified by Niparko et al. [5], who found higher parent-child interaction scores being significantly associated with greater rates of increase in comprehension and expression of spoken language [5]. These findings are supportive of the conclusion that variability in parental involvement, quality and quantity of parent-child interactions, and commitment to rehabilitation are significant factors in outcomes of children with cochlear implant and can lead to significant measurable differences in spoken language development after longer periods of time.

Objectives

This paper aims to study the perspectives of parents and guardians of children implanted in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. As identified previously, parental perspectives can be a factor contributing to a child’s outcomes particularly in the first few years after implantation. It is important therefore that parents have realistic expectations and information and are aware of their role in children’s development. Being a young program, it is believed that an insight into parental perspectives regarding cochlear implantation in Tanzania will aid clinicians in further understanding the factors that can cause variations in outcomes of these children, particularly in relation to family and social support, and will also show the extent to which parent’s expectations have been met post-implantation. This article therefore aims to address the following research questions:

a) What are parents’ expectations of cochlear implantation for their children prior to implantation with regards to listening without lip-reading, communicating with others, and the development of speech and language?

b) Post-implantation, what are parent’s experiences with their implanted children? Have they noticed positive changes in communication with others, listening without lip-reading, and in spoken language?

c) How do the changes noticed by parent’s post-implantation relate to their expectations in those specific domains?

d) Are parents still concerned about their children’s development in communication, listening without lip-reading, and spoken language at one-year post-implantation?

e) Are there any differences in parental perspectives of noticeable changes across the identified domains and in their concerns about the child’s development between parents of patients who have been implanted for longer when compared to more recent implantees?

Materials and Method

A prospective longitudinal study design was adapted to collect data from the parents of twenty-one children with a bilateral severe to profound hearing impairment who underwent cochlear implantation in Tanzania. A quantitative approach to data collection and statistical analysis was determined appropriate due to the advantage of quantitative research in giving an overview of the area being studied, allowing a description of parental perspectives towards cochlear implantation to be discerned. As this is the first study to research this domain in Tanzania, it is believed that the employment of quantitative data analysis will aid in guiding future qualitative studies that may be required to explore the topic in more detail (Kelle, 2006). Parent’s expectations pre-implantation and perspectives on outcomes post-implantation were thus recorded using a quantitative survey.

Participants

The participants of the survey were parents of children who underwent cochlear implantation in Tanzania between June 2017 and January 2019 (n=21). All children underwent comprehensive assessments as part of the candidacy evaluation for cochlear implantation outlined by recommendations made by the Cochlear Implant Group Tanzania (CIGT), undergoing extensive audiology, radiology, medical, psychological, and social assessments before being selected as suitable candidates [2]. Three children were excluded from this study; one child with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) identified through an audiological evaluation that revealed an abnormal auditory brainstem response and present otoacoustic emissions, which can be taken as evidence of ANSD [18]. Due to the variety of pathologies and wide variability in outcomes in children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder seen in other studies and the absence of an electrically evoked electrophysiology testing to predict benefit from implantation [13], outcomes and thus parental perspectives may be different from other children. The other child was identified by a pediatrician and a speech and language pathologist as a child with autism spectrum disorder, which can also result in different experiences and outcomes with cochlear implants when compared to the general pediatric implant population [19]. The third child to be excluded from the study suffered from a post-operative surgical site infection ten months post-implantation that resulted in inconsistent and eventually non-use of the processor, and subsequent explant of the device due to exposure of the implant.

All children (n=18) were implanted unilaterally with the twelve channel MED-EL Sonata Ti100 implant in combination with the 31.5mm ‘standard’ electrode array. All patients use the MED-EL Opus 2 behind-the-ear speech processor, have undergone mapping and follow up as clinically appropriate. The programming of their MAPs was conducted by audiologists trained in cochlear implant programming through a combination of behavioral and objective methods, using electrically evoked stapedial reflex thresholds (eSRTs) in fifteen children and electrically evoked compound action potentials (eCAPs) in three children. In patients with whom reliable feedback through behavioral techniques for speech processor programming is not obtainable, objective methods such as eSRTs and eCAPs have been shown to correlate significantly with behavioral thresholds and thus are useful with these populations, especially in pediatric implantees [20,21]. Out of these 18 children, 8 were male (44.4%) and 10 were female participants (55.6%). The mean age of all participants at the time of the post implant survey was 4.8 years, ranging between 4.1 years and 6.6 years. The mean age at implantation was 3.6 years, ranging from 2.3 years to 5.9 years. Between Group 1 and Group 2, the mean age at the time of the survey was the same (4.8 years). Age at implantation, however, varied significantly; the mean age at implantation for group 1 (n=8) was 3.0 years while the mean age at implantation for group 2 (n=10) was 4.1 years. The age ranges also varied between the two groups; group 1 participants ranged between 2.3 years to 3.7 years at the time of implantation, while group 2 participants ranged between 3.4 years to 5.9 years when implanted.

Measures

A questionnaire devised by Nikolopoulos, Lloyd and Archbold (2001) was determined suitable for the purpose of this study (Appendix 1), adapted from an article titled “Pediatric Cochlear Implantation: The Parent’s Perspective” (Nikolopoulos, Lloyd, & Archbold, 2001). The survey was administered after the completion of the patient’s candidacy assessment and decision to continue with implantation, having undergone all the necessary investigations outlined previously. Parents completed this questionnaire in writing within the final two weeks pre-implantation. Either one or both parents were present at this time. The pre-implantation survey required parents to respond regarding their expectations in three main areas;

a) Their expectations about the child’s communication with others

b) Listening to speech without lipreading

c) Their expectations of the implant’s effect on their child’s development of speech and language.

Post-implantation, questions were asked in relation to these three domains. The questionnaires were administered postimplantation with data collection from patients dependent on date of implantation. The patients have been divided into two groups; Group 1 (G1) being children who have been implanted for between one to two years, and Group 2 (G2) being children implanted for between six to twelve months. Surveys were once again completed in writing with either one or both parents. The three areas identified previously were enquired about in two subsets; the first asking parents if they noticed any positive changes in relation to

a) communication with others,

b) Listening to speech without lipreading and

c) development of speech and language, while the second enquired about the parent’s concerns about the child’s development in

i. Communication with others

ii. Listening to speech without lipreading and

iii. Spoken language

The format of the questions was the same as utilized by Nikolopoulos, Lloyd and Archbold [22], using a five-point Likert scale that allowed patients to choose an answer between ‘certainly yes’, ‘mostly yes’, ‘mostly no’, ‘certainly no’, or ‘unable to answer’ [22].

Results

Prior to the intervention, all parents responded positively to all three questions when asked whether they believe the device will help their child in communication with others, listening to speech without lipreading, and in the development of speech and language. 100% of responses (n=54) were either “Certainly Yes” (n=41, 75.9%) or “Mostly Yes” (n=13, 24.1%). Expectations were much higher with regards to communication and the development of speech and language, with 31 out of 36 responses across these two domains (86.1%) being “Certainly Yes”, signifying that the parents expected a definite improvement in these two areas after implantation. Much lower were the expectations of benefit in listening to speech without lip reading, as 10 out of 18 parents (55.6%) expecting a definite improvement (“Certainly Yes”), with the remaining 8 parents answering “Mostly Yes”. In communication with others when surveyed post implantation, 100% of parents were satisfied to some extent; 14 out of 18 parents responded “Certainly Yes” when asked if they noticed positive changes in this domain, while the remaining 4 parents responded “Mostly Yes”. An important difference can be noted between the responses from the two groups, with respondents from group 1 (who have been using the device for over one year) all answering “Certainly Yes” (n=8), while in group 2 (implant use less than one year) 60% of parents responded “Certainly Yes” and the remaining 40% responded “Mostly Yes”. These responses allow an insight into parent’s experiences of benefits with the device over time, as all parents perceived a difference in the child’s ability to communicate post implantation, but over time this difference was more noticeable and parents were more assured of the positive changes caused by the intervention. They also demonstrate that parental expectations prior to the surgery were sufficiently met by their experiences with the child’s ability to communicate with others post implantation in both groups.

A similar result was obtained when asking about noticeable positive changes in spoken language. All parents (n=18) responded either “Mostly Yes” (22.2%) or “Certainly Yes” (77.8%) to this question. The difference between the two groups was the same as with the question regarding communication with others: 100% of group 1 (n=8) parents noticed a definite improvement in spoken language in their children, while in group 2 (n=10) 60% of parents responded “Certainly Yes” and 40% responded “Mostly Yes”. These responses highlight that an improvement in spoken language also becomes more apparent as time of implant use increases, and that parental expectations in this domain are sufficiently met post implantation.

When asked about their experiences with their child’s ability to listen to speech without lip reading, less parents in both groups gave a definite “Certainly Yes” answer. Overall, 10 parents (55.6%) gave this answer, while 7 parents answered, “Mostly Yes”. These positive responses accounted for 94.4% of answers, as one parent answered, “Mostly No”. Looking at the individual groups, in group 1 five parents answered, “Certainly Yes” and the remaining three answered “Mostly Yes”. In group 2, five parents (50% of respondents) answered “Certainly Yes”, four parents answered, “Mostly Yes”, and one parent answered, “Mostly No”. This was the only instance where such an answer was recorded for questions related to positive changes noticed by the parents. It is possible that this may have been due to the parent’s high expectations of the child being able to understand speech without visual cues post implantation, or because of the relatively short duration of implant use and rehabilitation making changes in this domain less noticeable. This particular patient was the oldest implantees in the study, being implanted at the age of 5.9 years and having built up a reliance on lip reading even while wearing conventional hearing aids prior to implantation. To further look into parent’s perspectives post implantation, the next set of questions aimed to get an insight into their concerns regarding their child’s development in communication with others, listening to speech without lip reading, and spoken language. In Group 1, 54.2% of responses across all three domains were “Certainly No”, with all eight parents denying any concerns in communicating with others.

This highlights the benefits perceived from the surgery – all children were seen to be better at communicating, and parents were not worried about the development of this ability. In concerns about developing spoken language, 3 parents (37.5%) answered “Certainly No” and a further 3 answered “Mostly No”, while 2 parents (25%) answered “Mostly Yes”. This showed that even over a year after the surgery, parents still had some concerns about spoken language, although more qualitative studies would be needed to discern the exact areas of concern in this regard. For concerns about listening to speech without lip reading, 50% of parents selected “Mostly Yes” as their answer while the other 50% selected either “Mostly No” or “Certainly No”. This could be indicative of higher expectations in the child’s ability to listen without visual support. More parental concerns were noted in children implanted for less than one year. In Group 2, two (20%) parents answered, “Mostly Yes” with regards to concerns about development of communication with others, with the other eight parents answering, “Mostly No” and “Certainly No”. Five parents answered, “Mostly Yes” (50%) about their concerns in listening to speech without lip reading, and one parent in this domain answered “Certainly Yes”; 60% of responses in this area were therefore in the affirmative. With regards to development of spoken language, 40% of responses in this group were “Mostly Yes” and one parent answered “Certainly Yes”. The higher number of affirmative responses about concerns in the child’s development in Group 2 suggest that while parents may have noted a general improvement in some of their child’s abilities, they were still worried about development in other aspects, and that the outcomes perceivable by these parents in the time period post implantation may not have fully met their expectations of the benefit they may have thought they would see.

Discussion

The support an implanted child receives from their parents, environmental factors, and social surroundings are considered as influential factors on developmental outcomes, especially as time goes on [15]. Parental expectations of the surgery and their perspectives on the benefit can influence their attitudes towards rehabilitation and communication with the child, along with commitment to appointments, therapy, and home-based exercises. These expectations are swayed by a number of things: parent’s hopes that the implant will enable the child to develop and function normally [11], their observations of other implantees or hearing-impaired people, their experiences with the professionals they have met, the portrayal by the media of cochlear implants as a ‘cure’ for deafness [7], and the counselling they receive both pre-operatively and post operatively. Results obtained from this survey show that pre-implantation expectations for most, if not all, parents are quite high. They expect that the surgery will help the child in communication with others and in speech and language development, and most parents do not doubt the device’s ability to assist their children in this regard. This is consistent with findings from the study performed by Nikolopoulos et al. [21], wherein 81% and 86% of parents responded “Certainly Yes” in these two fields respectively. Although in listening to speech without lip reading only 35% of parents responded similarly, another 40% of parents responded “Mostly Yes” for this domain i.e. 75% of patients believed they will help the child in this domain to some extent [21].

Post implantation responses from parents in both groups generally show that their experiences with their children indicate to them that there are positive changes due to use of the device. Across both groups, 70.4% (38 out of 54) responses over all three domains were “Certainly Yes”, suggestive of a definite positive change being noticeable in the child. A further 27.8% (15 out of 54) responses were marked “Mostly Yes”, and only one response was “Mostly No”. This response was recorded in response to the ‘listening to speech without lip reading’ question by a parent from group 2 (0 – 1 years since implant), and therefore may be due to the relatively short time since implantation. As shown by the responses recorded by parents in group 1, after a year of implant use parents largely report positive changes in this domain too. This suggests that cochlear implantation has significantly met parental expectations recorded prior to implantation, possibly further reinforcing their efforts in rehabilitation and in support of the child. As time progresses, it can be deduced that parents see more of their expectations being met. Alternatively, this could also mean that parent’s expectations are lowered and more realistic as they realize the limitations of the device and the challenges posed to implantees, even though the surgery is seen to be greatly beneficial to the recipient.

Are parents still concerned about their children’s development in communication, listening without lip-reading, and spoken language at one-year post-implantation? The answers received about future concerns regarding the children’s development allow us to further understand expectations and perspectives, especially as time progresses and implant use increases. In group 1, 6 out of 24 (25%) answers were in the affirmative (all being “Mostly Yes”. 4 out of these 6 responses were with regards to listening to speech without lip reading. Meanwhile, in group 2, 13 out of 30 (43.3%) responses were in the affirmative, and 2 of these 13 answers were “Certainly Yes”. This answer was given by the parent of the oldest implantees across both groups (5.9 years being the age at implantation) when asked about concerns regarding development of listening to speech without lip reading and spoken language. Age at implantation being a significant factor in influencing outcomes post implantation [6,17], it could be a contributing factor in the parents’ concerns about their child’s development, particularly as professionals would ideally have made them aware of age’s influence on outcomes. Parent’s reports of their concerns also indicate that as implant use increases, they are less worried and concerned about outcomes. Boons et al. [17] found that over time, some of their study participants reported that their expectations changed over time, as they saw the child progress. A large variety was seen in parental expectations, with some parents reporting high expectations while others reported low expectations. Most parents noted that outcomes were largely in line with their expectations. This study had a relatively low sample size, and therefore a higher sample size would be desirable in generalizing the results to a wider population. A more long-term study could also be undertaken to highlight and understand variability in outcomes and parent’s experiences with their implanted children [23].

Conclusion

Between the results seen in both groups, a higher percentage of parents in group 1 have noticed positive changes across all three domains and have also reported being less concerned in all areas than parents of children in group 2. As time passes, children generally can be said to meet parent’s expectations more than at earlier stages after implantation. From the three areas considered in this study, they seemed to be more concerned about their child’s ability to listen to speech without lip reading, noticing a slower rate of improvement in this area than in the other domains. In conclusion, this study has given an insight into parental perspectives of cochlear implantation in Tanzania. Results are largely correlating with findings from studies in other countries and programs. However, further research is needed into other factors affecting outcomes, perspectives of implantees, and those of their families. Qualitative research into other factors influencing these influences on outcomes and expectations is needed, in order to highlight areas where professionals and parents can further collaborate in the process of cochlear implant and its rehabilitation.

References

- Niparko J (2009) Cochlear implants. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA.

- Cochlear Implant Group Tanzania (2016) Guidelines for the Cochlear Implant Programme in Tanzania. Tanzania ENT Society (TENTS).

- (2019) Cochlear implants for children and adults with severe to profound deafness | Guidance | NICE. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Campisi P, James A, Hayward L, Blaser S, Papsin B (2004) Cochlear implant positioning in children: a survey of patient satisfaction. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 68(10): 1289-1293.

- Niparko J (2010) Spoken Language Development in Children Following Cochlear Implantation. JAMA 303(15): 1498-1506.

- Geers A (2002) Factors Affecting the Development of Speech, Language, and Literacy in Children with Early Cochlear Implantation. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools 33(3): 172-183.

- Kampfe C, Harrison M, Oettinger T, Ludington J, McDonald Bell C, et al. (1993) Parental Expectations as a Factor in Evaluating Children for the Multichannel Cochlear Implant. American Annals of The Deaf 138(3): 297-303.

- Incesulu A, Vural M, Erkam U (2003) Children with cochlear implants: Parental perspective. Otology & Neurotology 24(4): 605-611.

- Weisel A, Most T, Michael R (2006) Mothers’ Stress and Expectations as a Function of Time Since Child’s Cochlear Implantation. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 12(1): 55-64.

- Geers A. (2006) Factors Influencing Spoken Language Outcomes in Children following Early Cochlear Implantation. Cochlear and Brainstem Implants 64: 50-65.

- Sach T, Whynes D (2005) Paediatric cochlear implantation: the views of parents. International Journal of Audiology 44(7): 400-407.

- Archbold S, Sach T, O neill C, Lutman M, Gregory S (2008) Outcomes from cochlear implantation for child and family: parental perspectives. Deafness & Education International 10(3): 120-142.

- Teagle H, Roush P, Woodard J, Hatch D, Zdanski C, et al. (2010) Cochlear Implantation in Children with Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder. Ear and Hearing 31(3): 325-335.

- Holt R, Beer J, Kronenberger W, Pisoni D, Lalonde K (2012) Contribution of Family Environment to Pediatric Cochlear Implant Users’ Speech and Language Outcomes: Some Preliminary Findings. Journal of Speech, Language, And Hearing Research 55(3): 848-864.

- Spencer P (2004) Individual Differences in Language Performance after Cochlear Implantation at One to Three Years of Age: Child, Family, and Linguistic Factors. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 9(4): 395-412.

- Nikolopoulos T, Gibbin K, Dyar D (2004) Predicting speech perception outcomes following cochlear implantation using Nottingham children’s implant profile (NchIP). International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 68(2): 137-141.

- Boons T, Brokx J, Dhooge I, Frijns J, Peeraer L, et al. (2012) Predictors of Spoken Language Development Following Pediatric Cochlear Implantation. Ear and Hearing 33(5): 617-639.

- (2019) Assessment and Management of Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder (ANSD) in Young Infants.

- Donaldson A, Heavner K, Zwolan T (2004) Measuring Progress in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Who Have Cochlear Implants. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 130(5): 666-671.

- Van Den Abbeele T, Noël Petroff N, Akin I, Caner G, Olgun L, et al. (2012) Multicenter investigation on electrically evoked compound action potential and stapedius reflex: how do these objective measures relate to implant programming parameters? Cochlear Implants International, 13(1): 26-34.

- Shapiro W, Bradham T (2012) Cochlear Implant Programming. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 45(1): 111-127.

- Nikolopoulos T, Lloyd H, Archbold S, O Donoghue G (2001) Pediatric Cochlear Implantation. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 127(4): 363.

- Holt R, Beer J, Kronenberger W, Pisoni D (2013). Developmental Effects of Family Environment on Outcomes in Pediatric Cochlear Implant Recipients. Otology & Neurotology 34(3): 388-395.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...