Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Mini Review(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Objective Evidence of the Presence of Sars-Cov-2 in the Middle Ear- A Review of the Reported Cases Volume 8 - Issue 1

Waqas Jamil1*, Farah Naz2 and Mark Simmons3

- 1ENT Department, Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham, UK

- 2Dow University of Health and Sciences, Pakistan

- 3Walsall Manor Hospital and University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Received: December 20, 2021; Published: January 11, 2022

Corresponding author: Waqas Jamil, ENT Department, Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham, UK

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2022.08.000276

Abstract

Introduction: The presence of new coronavirus in middle ear cleft can have significant safety implications on ENT practice

(e.g., viral shedding during ENT procedures including middle ear/mastoid surgery, ear micro-suction or intratympanic injections).

Objective: This review aims to analyse all available studies providing objective evidence about the presence or absence of

coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in the middle ear.

Methods: Standard search methodology was used to retrieve all studies dealing with the testing for the presence of coronavirus

(SARS-CoV-2) in the middle ear. Databases searched were PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and Embase. Only articles providing

objective evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in middle ear cleft were included i.e., where confirmation of viral presence was available through

a diagnostic test. Studies merely reporting middle ear symptoms without a diagnostic test were excluded.

Results: A total of 167 articles were obtained during the literature search, out of which a final 6 studies were included and

analysed. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the middle ear cleft was reported in 4 out of the 6 studies (10 out of a total of 20 patients

tested). Surprisingly, in one patient SARS-COV-2 was identified in the middle ear by PCR testing with a negative oropharyngeal swab

and no systemic features of SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusion: SARS CoV-2 was reported in the middle ear cleft of 50% (n=10/20) of patients included in our study. Based on our

study findings, SARS-CoV-2 should be suspected in every patient undergoing ontological procedure during covid-19 until proven

otherwise. The virus can be present in the middle ear in asymptomatic patients or/and patients with a negative oropharyngeal/

nasopharyngeal swab. Hence all necessary precautions must be undertaken during the otological procedures.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2; middle ear; mastoid cleft; coronavirus; COVID-19

Introduction

The novel strain of Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which emerged in late December 2019, has been found to be both highly infectious and virulent [1]. To the present day, SARS-CoV-2 has infected over 244 million people and caused nearly 5 million deaths worldwide [2]. The emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 strain causing the COVID-19 pandemic has caused the worldwide healthcare sector to face unusual clinical challenges in terms of caring for the patients while protecting the healthcare workers from catching the virus. Otolaryngologists are one of the most vulnerable and susceptible among the health professionals, with a higher risk of becoming infected with the coronavirus whilst conducting daily routine surgical and outpatient procedures due to exposure to the viruscarrying anatomical sites such as nasal mucosa, nasopharynx and oropharynx.

Rationale

We already know that other viruses can reside in the middle ear cleft. The presence of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in the middle ear cleft could have a significant impact on otology practices as the presence of the virus might result in viral spread/shedding during otological procedures i.e., middle ear surgery, drilling of mastoid cavity suctioning through tympanic membrane perforation and intratympanic injections.

Objectives

Our study aims to review the available evidence regarding the presence of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in the middle ear cleft.

Methods

We undertook a review of the current literature.

Eligibility criteria: Studies included in this review fulfilled the

following eligibility criteria:

a) Patient with confirmed coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) systemic

infection.

b) Presence of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in middle ear cleft

confirmed by a diagnostic test.

c) English language studies

We excluded the studies which only stated middle ear symptoms

subjectively in patients with COVID-19 infections but failed to

confirm the presence or absence of SARS-CoV-2 in the middle ear

based on a diagnostic test.

Study design: A literature review.

Search strategy: The literature search was based on two major

concepts: 1) middle ear cleft (middle ear and mastoid cavity) 2)

SARS-CoV-2 virus. Search terms included keywords, synonyms, and

subject headings. Synonyms used were “middle ear” OR “mastoid”

OR “ear” and “corona” OR “covid 19” OR “SARS-CoV-2”. A literature

search was performed on 24thOctober 2021. During the literature

search, no limitations/ filters were applied i.e., language, date, study

design, full text (appendix 1 literature search strategy PubMed).

Information sources: Databases searched were PubMed, CINAHL,

Cochrane Library and Embase.

Study selection

The first and second author (WJ and FN) conducted the literature search individually. Both the reviewers screened through the title, abstract separately. Full articles were reviewed where needed. Final articles were selected independently based on the eligibility criteria of the study.

Data collection process

The data collected included:

a. year and month study published

b. the total number of patients

c. study design

d. country

e. setting

f. diagnostic methods used

g. study findings.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

All studies included were assessed for risk of bias and quality.

A methodological quality assessment tool, by Murad et al. was used

for quality assessment of the included studies. Following areas

were explored during quality assessment process

a) clarity of patient selection method

b) exposure and outcome ascertained

c) other confounding factors excluded

d) enough case details given to ascertain external validity

[3].

Results and Analysis

Study selection

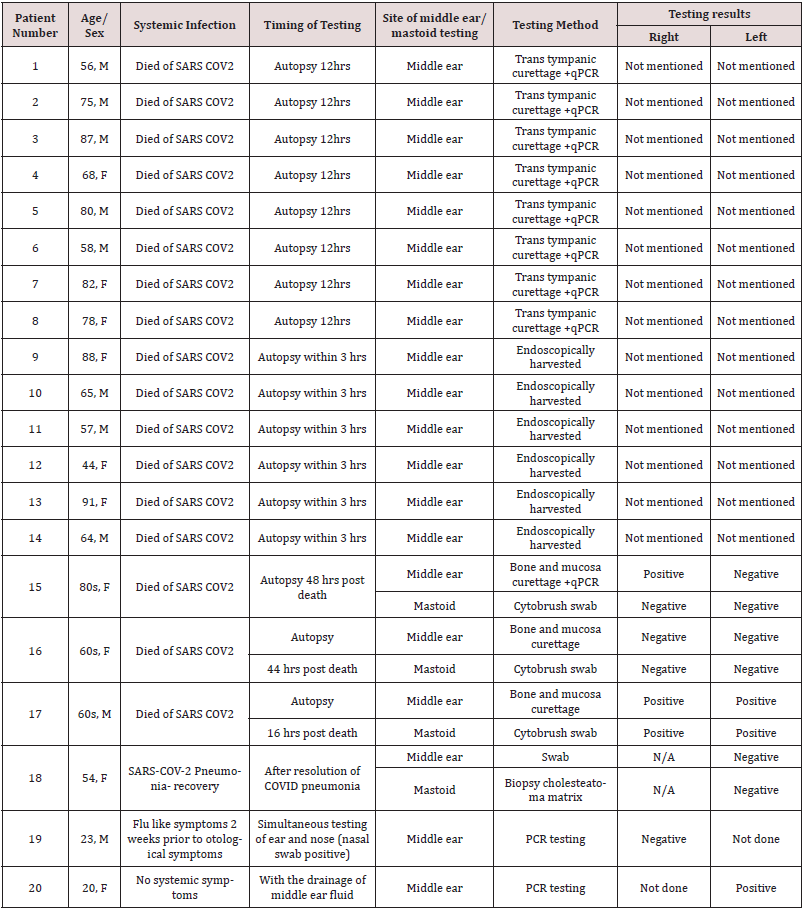

A total of 167 articles were found during the literature search. 149 articles were obtained after removing duplicates. These 149 articles were then screened by performing title and abstract reading (plus review of the full article when needed), out of which 142 articles were excluded (Figure 1). Full text of the remaining 7 articles was reviewed, out of which a further 1 were excluded based on eligibility criteria of our review. The remaining 6 articles were included in this review (Figure A). Raad et al. reported 8 covid -19 cases with middle ear effusion. Out of eight, only one patient fulfilled our study criteria i.e., diagnostic testing (PCR testing on middle ear fluid) was performed to check for the presence of coronavirus in middle and no testing was performed in the remaining 7 patients. Therefore, only one patient from this study is included in our review [4]. Similarly, Kurabi et al. reported 10 cases in which 6 had COVID-19 infections, whereas the rest 4 were control subjects with no Covid-19 infection. Therefore, our study included only 6 patients who met our inclusion criteria i.e., must have a covid-19 infection and diagnostic testing performed for middle ear virus detection [5].

Study characteristics

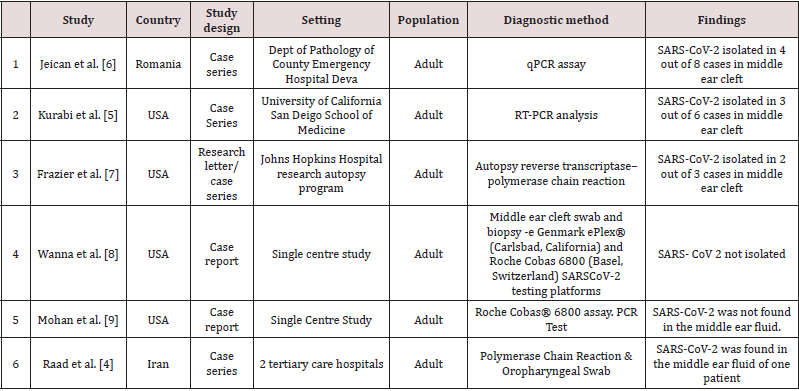

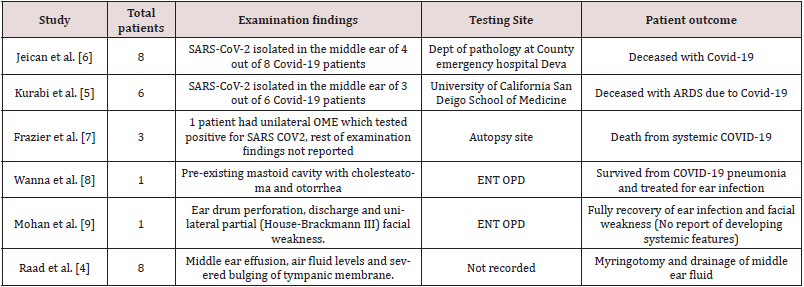

A total of 6 studies met the eligibility criteria of our review, reporting a total of 20 cases. All 6 studies included the patients who had suffered from COVID-19 infection and were tested for the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the middle ear and/or mastoid region. The age range was 20-91 years, 10 females and 10 male patients were included in the study. Two studies were case series, while the other two studies were case reports (Table 1).

Results of individual studies

Jeican et al. reported 8 patients with COVID-19 infection. The

tissue samples were collected from the ear (middle ear) and nose

(nasal mucosa-ethmoidal curettage)12 hours after death. Out of

8 patients, SARS-CoV-2 in the middle ear was found positive in a

total of 4(2 male and 2 female) covid-19 patients. However, lower

viral load was reported in the middle ear samples. Additionally,

none of the patients was reported to have any otological symptoms

during the hospital admission. Also, no sign of inflammation and

cytopathology was observed in the middle ear mucosal samples [6].

Kurabi et al. reported 6 patients who died of Covid-19 complications

(ARDS) (see above). An autopsy was performed to obtain nose and

middle ear mucosal samples via endoscopy to perform the qPCR test

for virus detection. SARS-CoV-2 was found positive in the middle

ear of 3 out of 6 COVID-19 patients (2 males,1 female). It further

revealed that viral load was higher in the nasal mucosa sample than

in the middle ear sample. Besides, no new otological symptoms

were reported in patients with covid-19 during admission [5].

Frazier et al. reported autopsy findings in three patients who

had died of COVID-19. All three patients underwent bilateral

mastoidectomy and sampling from the middle ear and mastoid

cavities. The first patient showed positive test results from both

the mastoid cavity and middle ear, while the second patient

showed negative test results in all samples from the mastoid and

middle ear. The third patient in this study had positive middle ear

effusion in one ear which tested positive for SARS-CoV- 2, while

the remaining three samples were negative in the same patient

[7]. Only one case from Raad et al. was included in this review

as discussed above. A 20-year-old lady with close contact with a

COVID-19 patient presented with unilateral otalgia and hearing

loss secondary to middle ear effusion. PCR on the middle ear fluid

confirmed the presence of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in the middle ear. This patient had no systemic features of coronavirus (SARSCoV-

2) infection, no radiological evidence of lung involvement

based on CT chest findings and a negative oropharyngeal swab [4].

Wanna et al. reported a case of SARS-CoV- 2 pneumonia, where the

patient also developed ear symptoms comprising ear pain, aural

fullness, and purulent discharge subsequently (patient had a preexisting

mastoid cavity from previous surgery). The patient was

given topical ear drops (ofloxacin otic) for ear symptoms after a

video consultation. The patient was reviewed in ENT outpatient

once symptoms of pneumonia were resolved, and samples were

sent from the middle ear and mastoid cavity. However, all the test

results from these samples taken came back negative [8]. The case

report by Mohan et al. presented a case of a COVID-19 patient who

developed acute otitis media with tympanic membrane perforation

and facial paresis. A nasopharyngeal sample and ear drainage fluid

sample was taken for SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing. The results revealed

positive findings of COVID-19 in the patient but, no corona virus

(SARS-CoV-2) was detected in the ear fluid samples [9] (Table 2).

Risk of bias within & across the studies

Timing of corona virus (SARS-CoV-2) testing is important because delayed testing can influence results e.g., patient clinically asymptomatic for pneumonia when testing performed an autopsy delayed for 48 hrs [7,9]. Lack of sensitivity and specificity of coronavirus diagnostic tests can be another reason behind negative test results [10]. Moreover, it is not clear in Raad et al. as why SARSCoV- 2 middle ear PCR testing was performed in only one patient rather than in all eight patients [4].

Discussion

Key findings

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review, integrating all available objective evidence about the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the middle ear. We found 4 studies from the USA,1 from Iran and 1 from Romania (4 case series and 2 case reports), reporting a total of 20 patients with COVID-19 infection in which the middle ear was also tested to check for the presence or absence of SARS- CoV- 2 in the middle ear/mastoid region. Altogether, 4 studies confirmed the presence of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in the middle ear [4-6]. Even patients without otological symptoms were found to have the virus present in their ears [4-6]. Interestingly, 1 study reported presence of SARS-CoV-2 confirmed by PCR testing in the middle ear fluid of a patient with no COVID-19 systemic features and a negative oropharyngeal swab [4].

Comparison with previous literature

Viruses are the predominant cause of acute otitis media in nearly 70% cases [11,12]. The possibility of Coronaviruses in the middle ear and mastoid was already established by previous studies during pre-covid era [12]. With the onset of a COVID-19 pandemic, studies doubted that SARS-CoV-2 could be a possible cause behind the otological problems such as otalgia, AOM and SSNL in COVID-19 patients [13,10]. The evidence of contemporary research studies showed that those doubts were true [7,8]. So far, studies have investigated the presence of corona virus (SARS-CoV-2) in external ear (cerumen) and middle ear cleft [4-7,14] development of middle ear signs/ symptoms in patients with systemic corona virus infection [8,15-17] and the probability of viral transmission during otological procedures [6,18,19].

Strengths & Limitations

This study investigated for the objective evidence of the presence SARS-CoV- 2 in middle ear cleft rather than subjective symptoms, which could be due to other pathogens. We only found a limited number of studies testing for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the middle ear cleft [20].

Clinical implications

The included studies suggested that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the middle ear (even in asymptomatic patients) pose a serious risk of infection to healthcare professionals during otological procedures [6]. Since virus-contaminated blood and bone particles, in the form of aerosol from procedures (e.g, middle ear/mastoid surgery, ear micro-suction or intratympanic injections), can be dispersed and cause viral transmission to the surgical staff [21,22,6]. Therefore, healthcare professionals need to undertake all necessary safety precautions and wear personal protective equipment during otological procedures irrespective of the patient’s COVID-19 status. Similarly, more use of curette and trans-canal endoscopic surgery as a possible alternative to traditional mastoidectomy in suitable cases can help reduce viral shedding associated with drilling.6 Vitcom 3D system has been used in the UK to perform otological surgery safely during the pandemic to reduce viral spread [22].

Knowledge gaps and directions for future research

So far, we are not aware of a reported case of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during otological procedures. It is thus uncertain whether the mere presence of this virus in the middle ear means the patient may be infective to health care professionals. Secondly, the survival and shedding period of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in the middle ear cleft still needs to be investigated. Whether there is a correlation between the severity of systemic disease and the probability of (SARS-CoV-2) in the middle ear cleft is yet to be ascertained.

Conclusion

Current evidence confirms the presence of coronavirus (SARSCoV- 2) in the middle ear, even in patients without systemic signs/ symptoms and a negative oropharyngeal swab. Alternatively, otological features could be the sole manifestation of COVID-19 infection, therefore, full personal protective equipment should be used by health care professionals during invasive otological procedures.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Shweta Pawar from Walsall Manor Hospital, for helping us in analysing the data from studies for review.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics and dissemination

No ethical approval was required for the protocol and proposal of this review.

References

- Ayache S, Schmerber S (2020) Covid-19 and otologic/neurotologic practices: Suggestions to improve the safety of surgery and consultations. Otol Neurotol 41(9): 1175–1181.

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.

- Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F (2018) Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med 23(2): 60–63.

- Raad N, Ghorbani J, Mikaniki N, Haseli S, Karimi-Galougahi M (2021) Otitis media in coronavirus disease 2019: a case series. J Laryngol Otol 135(1):10–13.

- Kurabi A, Pak K, DeConde AS, Ryan AF, Yan CH (2021) Immunohistochemical and qPCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the human middle ear versus the nasal cavity: Case series. Head Neck Pathol 28: 1-5.

- Jeican II, Aluaș M, Lazăr M, Barbu-Tudoran L, Gheban D, et al. (zier) Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in the middle ear of deceased COVID-19 patients. Diagnostics (Basel) 11(9): 1535.

- Frazier KM, Hooper JE, Mostafa HH, Stewart CM (2020) SARS-CoV-2 virus isolated from the mastoid and middle ear: Implications for COVID-19 precautions during ear surgery: Implications for COVID-19 precautions during ear surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146(10): 964–966.

- Wanna GB, Schwam ZG, Kaul VF, Cosetti MK, Perez E, et al. (2020) COVID-19 sampling from the middle ear and mastoid: A case report. Am J Otolaryngol 41(5): 102577.

- Mohan S, Workman A, Barshak M, Welling DB, Abdul-Aziz D (2020) Considerations in management of acute otitis media in the COVID-19 era. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 130(5): 520-527.

- Watson J, Whiting PF, Brush JE (2020) Interpreting a covid-19 test result. BMJ 369: 1808.

- Ruuskanen O, Arola M, Putto-Laurila A, Mertsola J, Meurman O, et al. (1989) Acute otitis media and respiratory virus infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J 8(2): 94–99.

- Bulut Y, Güven M, Otlu B, Yenişehirli G, Aladağ I, et al. (2007) Acute otitis media and respiratory viruses. Eur J Pediatr 166(3): 223–228.

- Koumpa FS, Forde CT, Manjaly JG (2020) Sudden irreversible hearing loss post COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep 13(11): 238419.

- Islamoglu Y, Bercin S, Aydogan S, Sener A, Tanriverdi F, et al. (2021) Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in the cerumen of COVID-19-positive patients. Ear Nose Throat J 100(2_suppl):155S-157S.

- Fidan V (2020) New type of corona virus induced acute otitis media in adult. Am J Otolaryngol 41(3): 102487.

- Maharaj S, Bello Alvarez M, Mungul S, Hari K (2020) Otologic dysfunction in patients with COVID ‐19: A systematic review. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 5(6).

- Zahran M, Ghazy R, Ahmed O, Youssef A (2021) Atypical otolaryngologic manifestations of COVID-19: a review. Egypt J Otolaryngol 37(1).

- İslamoğlu Y, Ayhan M, Bercin S, Kaya Kalem A, Kayaaslan B, et al. (2021) Evaluation of middle ear and mastoid cells of COVID-19 patients. atfm74(1): 130–133.

- Lokesh PK, Chowdhary S, Pol SA, Rajeswari M, Saxena SK, et al. (2020) Quantification of biomaterial dispersion during otologic procedures and role of barrier drapes in Covid 2019 era – a laboratory model. J Laryngol Otol 134(11): 975–980.

- Liaw J, Saadi R, Patel VA, Isildak H (2021) Middle ear viral load considerations in the COVID-19 era: A systematic review: A systematic review. Otol Neurotol 42(2): 217-226.

- Hilal A, Walshe P, Gendy S, Knowles S, Burns H (2005) Mastoidectomy and trans-corneal viral transmission. Laryngoscope 115(10): 1873–1876.

- Ally M, Kullar P, Mochloulis G, Vijendren A (2021) Using a 4K three-dimensional exoscope system (Vitom 3D) for mastoid surgery during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Laryngol Otol 135(3): 273–275.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...