Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Case Report(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Idiopathic Recurrent Meningitis-A Rare Presentation of Congenital Peri lymphatic Fistula Volume 4 - Issue 5

Anand R*, Sankya Shanmugam and Minu Madeswaran

- Department of Otolaryngology, Anand ENT Hospitals Coimbatore, India

Received: July 18, 2020; Published: August 07, 2020

Corresponding author: Anand R, Department of ENT, Anand ENT Hospitals Coimbatore, India

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2020.04.000198

Abstract

Perilymph fistula is caused by an abnormal communication between the perilymph space and the middle ear. It can either be congenital or acquired. In patients presenting with idiopathic bacterial meningitis, we as otolaryngologists should have a high index of suspicion towards peri lymphatic fistula. Nowadays, with screening of newborn with Computed Tomography temporal bone , inner ear malformations have been diagnosed more often without any signs of meningitis. We here present a case of congenital perilymph fistula in a pediatric patient with recurrent episodes of idiopathic meningitis. A brief review of the literature on this entity confirms the difficulty of making a definitive diagnosis in most cases.

Keywords: Perilymph fistula; idiopathic recurrent meningitis; CSF leak

Abbreviations: CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid; PLF: Peri Lymphatic Fistula; HRCT: High Resolution Computed Tomography

Introduction

Congenital Peri lymphatic fistula are spontaneous leaks of perilymph (cerebrospinal fluid) into the middle ear as a result of a congenital weakness or defect in the temporal bone with no previous history of trauma and exertion. Recurrent meningitis secondary to congenital labyrinthine anomaly is relatively a rare clinical entity and its diagnosis depends on clinical, radiological and intra operative features.

Procedure

We present a case of recurrent meningitis secondary to

congenital peri lymphatic fistula. 7-year-old boy was referred from

pediatric department to us to rule out any ENT foci for recurrent

Idiopathic meningitis.

Patient suffered from four episodes of meningitis in the past

and had about every six months and he recovered completely

after each episode .He underwent all the necessary investigations

which was found to be normal. MR imaging of brain was normal.

Lumbar puncture showed picture of meningitis ,but foci of infection

could not be found. He was referred to us when he gave a peculiar

history URI and earache which preceded an episode of meningitis.

Initially it was suspected that the foci of infection were from tonsils,

for which he underwent adenotonsillectomy, despite that he again

developed meningitis with complaints of ear fullness and hearing

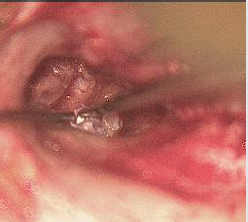

loss. Otoendoscopic findings in the right ear showed clear fluid

behind intact tympanic membrane and left ear was found to be

normal. Audiometry showed moderate to severe sensorineural

hearing loss & Tympanometry showed B type tympanogram in

the right ear. Since fluid was in the middle ear, Perilymph fistula

was suspected. Myringotomy was performed. Clear fluid from the

middle ear was sent for CSF analysis and was confirmed to be the

same. Computed tomography of temporal bone showed defect

at the junction of footplate of stapes and promontory (Figures

1-3). Tympanmastoid exploration was performed. Intraoperative

findings showed clear fluid between footplate junction and facial

canal. Head of malleus and incus were removed and examined for

any defect in areas of attic and eustachian tube .The site of leak

was confirmed and was covered with fat, temporalis muscle and

temporalis fascia (Figures 4-7). Patient was in regular follow up for

next 1 year and there were no further episodes of meningitis.

Discussion

Bacterial meningitis in childhood is a life-threatening infection

of the central nervous system that is mostly associated with

inner ear malformations and Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) leaks. Up

to 33% of cases of repeated meningitis in children are caused by

otolaryngologic etiologies [1] Congenital peri lymphatic fistula

(PLF) is an abnormal communication between the middle and

inner ear. It may be associated with micro fissures around the oval

and round windows or labyrinthine (IAM dysplasia) [2]. The basic

abnormality is a fistulous communication between the inner ear and

the intracranial compartment as well as another communication

between the inner ear and middle ear. In some cases, as in Hyrtl’s

fissure, there is a direct communication between the subarachnoid

space of the posterior cranial fossa and the middle ear [3].

Developmental anomaly: The otic placodes develop from

the ectoderm at the third week of intrauterine life and invaginate

to form otic vesicles. These subsequently develop to form the

endolymphatic sac, cochlea, and vestibule by the fifth week. The

membranous cochlea develops 1.5 turns at the end of 6 weeks

and 2.5 turns by the end of the seventh week. The semicircular

canals develop by the eighth week. The development of the inner

ear is almost complete by the eighth week, so any insult during

this period can produce several anomalies including congenital

perilymph fistula [3].

Diagnosis of PLF, however, is quite difficult and delayed because

of low index of suspicion and the main challenge is the identification

of those patients that need to undergo an exploratory tympanotomy

[4], there are no clinical-audiologic symptoms or radiographic

indicators that can be considered pathognomonic of perilymph

fistula. Hearing loss may be there which can be either fluctuating,

progressive, or sudden. It can be associated with vertigo; patient

may present with meningitis Establishing a causal relationship

between the inner ear and repeated episodes of meningitis

involves detailed audiologic and radiologic investigations [2].

Testing for beta-2 transferrin may yield results, but the only true

way to diagnose for PLF is intraoperatively [4]. Choice of Imaging

Modality is High Resolution Computed Tomography of Temporal

bone Bony delineation is well defined with HRCT and thin slice

MRI of temporal bone can highlight fluid filled communications [5-

7]. The most frequent middle ear anomalies identified in children

with congenital PLF are a deformity of the stapes and lateral-facing

round window [8]. Certain type of malformation of the inner ear,

with spontaneous peri lymphatic fistula is seen

a) An internal auditory meatus in the form of a funnel, in

which the narrow part corresponds to the fundus of the internal

auditory meatus.

b) A generalized dilatation of the osseous labyrinth, different

from Mondini’s malformation, in which only the basal turn

of the cochlea, the aqueduct of the vestibule and the lateral

semicircular canal are affected [9].

Inner ear malformations may involve bone defects of the

stapes footplate. Rao et al. reported that 59% of cases of repeated

bacterial meningitis in children were due to anatomical congenital

malformations of the temporal bone [10]. Savva et al. [4] reported

that persistent CSF leaks from inner ear malformations were

observed in 15% to 25% of repeated bacterial meningitis cases in

children [11]. Surgical exploration is required in case of recurrent

meningitis. Obliteration of the fistula with temporal muscle and

fascia has prevented the recurrence of meningitis. the middle ear

exploration is considered to be less difficult and more reliable than

the intracranial approach. In repairing the CSF leak, many different

materials and tissues have been used, including temporal fascia,

temporalis muscle, siliconized rubber, absorbable gelatin film, and

acrylic compounds [12,13].

Conclusion

The diagnosis of perilymph fistula is controversial. The variability among patients makes perilymph fistula difficult to diagnose. High index of suspicion should be there for inner ear anomaly if a patient presents with recurrent episodes of idiopathic meningitis. Undiagnosed cases will have high mortality rate. Paediatric congenital perilymph fistula will not have classical symptoms as in adults hence early diagnosis and management is important.

References

- Rupa V, Agarwal I, Rajshekhar V (2014) Congenital perilymph fistula causing recurrent meningitis: lessons learnt from a single-institution case series. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 150(2): 285-291.

- Jonathan P Harcourt (2018) Vestibular Rehabilitation. Scott Brown’s Textbook of Otolaryngology-Audit audiology. 8th Edn 1: 111-112.

- Rupa V, Rajshekhar V, Weider DJ (2000) Syndrome of recurrent meningitis due to congenital perilymph fistula with two different clinical presentations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 54(2-3): 173–177.

- Weber PC, Kelly RH, Bluestone CD (1994) Beta-2 transferrin confirms perilymphatic fistula in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 110(4): 381-386.

- Bluestone CD, Klein JO (2001) Otitis media in Infant and children .Philadelphia Saunders pp. 239-241.

- Johnson DB, Brennan P, Toland J, O Dwyer AJ (1996) Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. Clin Radiol 51(12): 837–841.

- Gupta V, Goyal M, Mishra NK, Sharma A, Gaikwad SB (1997) Positional MRI: a technique for confirming the site of leakage in cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Neuroradiology 39(11): 818–820.

- Isono M, Murata K, Aiba K, Miyashita, Weissman JL, Weber PC, Bluestone CD (1994) Congenital perilymphatic fistula: computed tomography appearance of middle ear and inner ear anomalies. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 111(3 Pt 1): 243–249.

- Phelps P, Lloyd GAS (1978) Congenital deformity of the internal auditory meatus and labyrinth associated with cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Adv Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 24: 51-57.

- Rao AK, Merenda DM, Wetmore SJ (2005) Diagnosis and management of spontaneous CSF otorrhoea. Otol Neurotol 26(6): 1171-1175.

- Savva A, Taylor MJ, Beatty CW (2003) Management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks involving the temporal bone: report on 92 patients. Laryngoscope 113(1): 50-56.

- Farrior B, Endicott JN (1971) Congenital mixed deafness: Cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea: Ablation of the aqueduct of the cochlea. Laryngoscope 81(5): 684-699.

- Bottema T (1975) Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea: Congenital anomaly of bony labyrinth a possible cause. Arch Otolaryngol 101: 693-694.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...