Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Hyperacusis In Nigeria: A Scoping Review Volume 6 - Issue 3

Osuji AE* and Nwogbo A

- Ear, Nose and Throat Department, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

Received: May 01, 2021 Published: May 10, 2021

Corresponding author: Osuji AE, Ear, Nose and Throat Department, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2021.06.000239

Abstract

Introduction: Hyperacusis is the sensitivity or intolerance to some everyday sound in such a way that it causes significant distress to the person, and impairs their social, recreational, occupational and day to day life. Most patients have a normal or nearnormal pure tone hearing threshold, with a decreased loudness discomfort level. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been reported to be effective in relieving the distress caused by hyperacusis in patients. There is a rarity of data on hyperacusis in Nigeria, probably being submerged in the general perception as incidents of delusive tendency. This scoping review aimed to examine the range and nature of available research on hyperacusis in Nigeria and to identify the research gap in the literature to aid conception of future hyperacusis research in Nigeria.

Method: A systematic widespread internet-based search of available literature on “Hyperacusis in Nigeria” was carried out using Medline, Scopus, Google Scholar, Embase, Ecosia, UCL Web of Science, African Index Medicus Database, and outcome of search reported. GOOGLE NGRAM was used to depict history of literature on hyperacusis.

Results: Seven search engines applied, Scopus and African index medicus database found one article each for ‘hyperacusis in Nigeria’. Google NGRAM showed that hyperacusis was first reported in the 19th century.

Conclusion: The paucity of research on hyperacusis in Nigeria is a reveille to scholarly researchers to take a deep dive into the swirling pool of hyperacusis research. The onus is not just otorhinolaryngologists, but also on audiologists, psychotherapists, mental health physicians, family physicians and others allied professionals to have a high index of suspicion and to report cases of hyperacusis to build up research database.

Keywords: Hyperacusis; sound sensitivity; tinnitus; misophonia; recruitment; Nigeria

Abbreviations: LDLs: Loudness Discomfort Levels; ULLs: Uncomfortable Loudness Levels; CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Introduction

Hyperacusis is the sensitivity or intolerance of some everyday sound in such a way that it causes significant distress to the person, and impairs their social, recreational, occupational and day to day life [1]. Hyperacusis was first reported in the 19th century when it was mentioned in the quarterly homoeopathic journal volume 1-2 released in 1853 [1]. Due to sound intolerance, sounds which are generally of normal loudness may be perceived as being either uncomfortably loud, annoying, frightening, or painful [2]. For instance, the sound of a car horn, chewing, or talking can be distressful to the patient and can impair their social, occupational, recreational or day to day life. Hyperacusis is caused by an increased neuronal gain in the auditory system [3]. Tyler et al. stated that type 2 nociceptive fibres are carried in the auditory nerve fibres which synapse with the inner and outer hair cells, and this explains the pain associated with auditory pathologies like hyperacusis [4]. However, according to Baguley, 2013, hyperacusis is due to a lesion in the insular cortex [5]. The onset of hyperacusis usually follows loud sound exposure, or symptoms are usually tied to a similar acoustic stimulus. Hyperacusis affects 1 in 10 adults/children and is associated with tinnitus, autism, dementia, pain syndromes and depression [6]. No standard clinical guideline has been issued in line with the management of hyperacusis, and some physicians often face the challenge of distinguishing hyperacusis from other sound-related pathologies [4].

It is characterized by abnormal loudness perception; thus, measurements of loudness discomfort levels (LDLs) and loudness growth have been used to study hyperacusis [1]. As a result of this peculiar features, hyperacusis can be said to be “pain hyperacusis” or “loudness hyperacusis”. Pain Hyperacusis is when pain is perceived from sounds that are at a relatively lower level than the threshold of stimulation of auditory pain [2,5]. Normal auditory pain threshold is 130-140dB SPL, however, patients with Pain hyperacusis experience pain at a sound level lower than this auditory pain threshold [6]. The mechanism underlying this pathological activation of the auditory pain threshold is still unknown [3]. On the other hand, loudness hyperacusis refers to the changed perception of the loudness of sound reported by these patients with decreased sound tolerance [5,7]. This implies a steeper loudness growth, similar across frequencies, with a narrow dynamic range [3]. The altered loudness perception can be due to fear of pain that will be elicited from the sound [4]. Most patients have a normal or near-normal pure tone hearing threshold, but a decreased loudness discomfort level [1]. Assessment of this condition involves pure tone audiometry, measurement of uncomfortable loudness levels (ULLs), combined with the use of self-report questionnaires, usually the hyperacusis questionnaire [2]. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been reported to be effective in relieving the distress caused by hyperacusis in patients [4]. This therapy has also been reported useful in the management of other sound-related conditions like Tinnitus and Misophonia [4]. There is a rarity of data on hyperacusis in Nigeria, either due to the condition being under-diagnosed by physicians, or under-reported probably being submerged in the general perception as incidents of delusive tendency. However, whatever the reason, hyperacusis has remained undocumented in the Nigerian research literature. This scoping review aimed to examine the range and nature of available research on hyperacusis in Nigeria and to identify the gap in the literature to aid planning or conception of future hyperacusis research in Nigeria.

Method

A systematic widespread internet-based search of available literature on “Hyperacusis in Nigeria” was carried out using the following 7 search engines: Medline, Scopus, Google Scholar, Embase, Ecosia, UCL Web of Science, African Index Medicus Database. This internet search was carried out in January 2020. The outcome of the search was documented, and the information contained in the finding was reported. GOOGLE NGRAM was later used to graphically depict the history of literature on hyperacusis from its first use to its recent surge.

Results

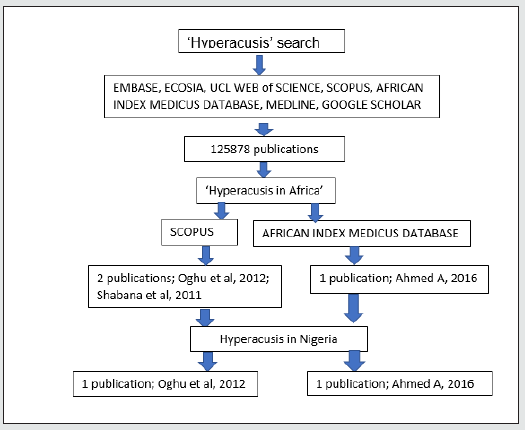

The search engines applied yielded hundred to thousands of articles, however when narrowed down to Africa and Nigeria, most of them yielded zero results. This is shown in the schematic representation of the search in Figure 1 below. Figure 1 shows that Scopus and African Index Medicus Database found one article each as a search result for hyperacusis in Nigeria, Oghu et al. and Ahmed A respectively. Google NGRAM (Figure 2) showed that hyperacusis was first reported in the 19th century, with a great surge in literature at the end of the 20th century which has remained till date.

Discussion

This study showed that Oghu et al. [8] was the only study from the SCOPUS search engine carried out in Nigeria that mentioned hyperacusis. It was a study on ‘tinnitus and its association with the use of earphones in students at college of medicine, University of Lagos, Nigeria’. Ahmed, et al. [9] was the only study from the African Index Medicus Database search engine that mentioned hyperacusis and was carried out in Nigeria. It is a study on self-reported hearing complaints in dental professionals carried out in Kano, Nigeria. In both studies, hyperacusis was mentioned passively. The additional study highlighted in the ‘Hyperacusis in Africa’ literature search using the Scopus search engine was the study by Shabana et al. [10] on Assessment of Hyperacusis in Egyptian patients: Evaluation of the Arabic version of the Khalfa questionnaire. This was carried out in Egypt, and the research was actively on the hyperacusis subject matter. These findings from this review study show a scarcity of hyperacusis research not just locally in Nigeria but in Africa generally. This scarcity of research on hyperacusis in Nigeria can generally be attributed to poor awareness on hyperacusis of the clinicians and individuals in Nigerian society. Besides, this scarcity of data on hyperacusis can be due to the belief system in Nigeria, where such symptoms seen in hyperacusis are regarded purely as a “psychiatric disorder” or worse still as a “spiritual attack” by the sufferer and their families. This belief makes them seek treatment in prayer houses or fetish shrines rather than hospitals.

On the other hand, the low level of understanding of the hyperacusis subject matter by clinicians imply a low index of suspicion and non-diagnosis of this condition even when such patients present to hospital. Thus, there is need to beam the enlightenment and research searchlight on hyperacusis to improve awareness especially on the part of the clinicians, so that cases of hyperacusis can easily be identified when they present to the hospital. An improved clinician’s index of suspicion will enhance diagnosis of hyperacusis, and subsequently increase research and data on hyperacusis in Nigeria in due course. An understanding of the peculiarities of hyperacusis, in line with its presentation, assessment and treatment is imperative to its identification and management in the clinic. This would improve the diagnostic dilemma of physicians in the identification of cases in the clinic and improve research on hyperacusis in Nigeria. Hyperacusis can be mistaken for tinnitus, misophonia, phonophobia or recruitment, but there are subtle differences among them. However, despite these differences, these conditions can co-exist in an individual [11].

Hyperacusis and Tinnitus

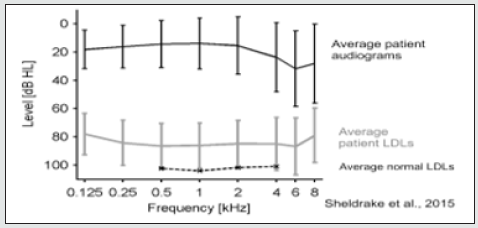

Tinnitus is defined as an acoustic sensation without an external auditory stimulus [7]. Hyperacusis is abnormal sound sensitivity arising from the auditory system, either peripheral or central. Similarly, tinnitus has been noted to arise from the auditory system, peripheral or central, and may be present in hyperacusis, but loudness discomfort level (LDL) abnormality in audiological examinations or investigations are noted with true hyperacusis [2]. Figure 3 shows a normal PTA of a hyperacusis patient with reduced loudness discomfort levels (LDL). The figure 3 also shows LDL for hyperacusis patient (grey line) which can be compared to LDL for normal patients (black broken line) [2]. It has been noted that in tinnitus there may be an underlying hearing loss, and there is an increased neuronal gain in such individuals which may be due to peripheral hearing loss [6,7]. In response to the inconsistent neural input, the auditory cortex may adapt and remodel transmitted sound. The resultant neuroplasticity may lead to the perception of phantom sounds (tinnitus) and can also increase the perception of normal sound in the brain leading to hyperacusis [5,11]. Hyperacusis patients have an auditory gain which is usually set on ‘extremely loud’ by the brain when there is the anticipation of trigger sound [6]. Despite this, most hyperacusis patients have been shown to have normal PTA thresholds [3,12].

Hyperacusis and Misophonia

Fear of sound known as phonophobia or a strong dislike of sound called misophonia, and phonophobia is an extreme of Misophonia [6]. It has been reported that specific sounds cause aversive reactions regardless of sound intensity [13]. In misophonia or phonophobia, a patient has abnormally strong reactions of limbic and autonomic nervous systems but no significant activation of the auditory system, unlike in hyperacusis [13]. Besides, audiologic and audiometric assessments are normal in misophonia or phonophobia in contrast to hyperacusis [6].

Hyperacusis and Recruitment

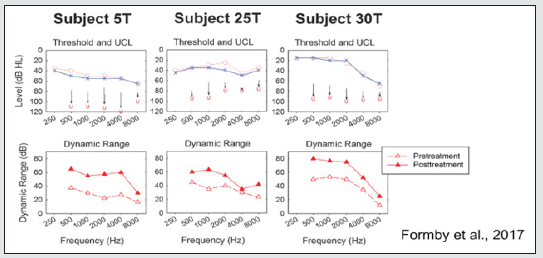

Figure 5: Serial Pure tone audiograms showing improvement in Threshold and dynamic range with the treatment of hyperacusis [15].

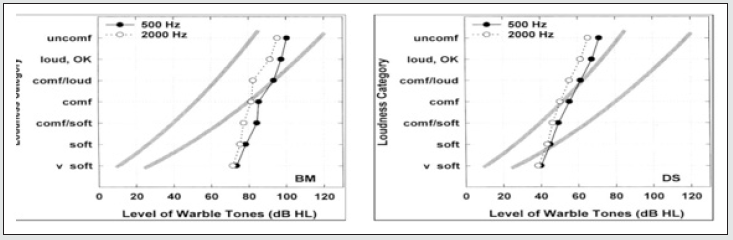

Hyperacusis is a symptom often defined as loss of normal dynamic range of hearing in an ear essentially normal in hearing thresholds [11]. Recruitment is abnormal sound growth in presence of hearing loss usually caused by a retro-cochlear pathology [14]. Both conditions can be differentiated by abnormal findings on audiological and radiological evaluations seen in recruitment. However, recruitment does not vary with the emotional state [14]. Abnormal loudness growth in recruitment occurs around 70dBHL while abnormal loudness growth in hyperacusis occurs at 40dBHL (see Figure 4). There is a reduced dynamic range in both recruitment and hyperacusis, when compared to normal dynamic range. (grey bold lines on Figure 4) [14].

Assessment of Hyperacusis

The assessment of hyperacusis begins with a thorough history which should provide answers to specific questions like “what sound triggers symptom?” “which situation is the sound heard?” “What is the patient’s reaction to sound?” “What impact does this have on the patient’s daily life and personality?” “What is the safety behaviour exhibited by the patient?” [1]. Hyperacusis questionnaire is an important assessment tool, using the Khalfa scale.[10] It helps to assess the level of distress associated with symptoms of hyperacusis in a particular patient. The MASH (multiple activity scale for hyperacusis), or Inventory for hyperacusis symptoms, are also questionnaires or tools that can be used to assess hyperacusis [1]. Patient’s evaluation will also include pure tone audiometry, to evaluate the uncomfortable loudness level (ULL) or loudness discomfort level (LDL) [2]. Tympanometry and acoustic reflex will help to establish or rule out the presence of recruitment. Radiological investigations are usually required to rule out other pathologies that may be present or may be responsible for any retro-cochlear pathology [1]. Psychological or mental assessment have a role to play in hyperacusis investigation because it has been associated with dementia, depression, autism, etc. [7].

Treatment of Hyperacusis

Treatment of hyperacusis should be done via a multidisciplinary team approach, involving the otorhinolaryngologist, audiovestibular physician, audiologist, mental health physician, and psychotherapist [1]. Cognitive behavioural therapy involves counselling, and this helps to relieve the distress associated with hyperacusis [1]. Sound therapy which involves exposing the patient to controlled sounds on regular basis to habilitate the brain into accepting identified sound which triggers symptoms. This can be done using sound generators like hearing aids [14]. During treatment, there is a need for serial PTA to monitor ULL. Follow up and monitoring is essential to evaluate treatment and interventions [15]. It has been reported that LDLs/UCLs can increase with treatment, especially using sound generators (Hearing aids) and counselling [15]. The study by Formby et al, 2017 have shown that hyperacusis treatment can be effective. They reported serial LDL of patients after 5 to 30 weeks of treatment, with an improved uncomfortable loudness (UCL) and a widened dynamic range [15]. Available evidence has shown that with treatment & follow-up, hyperacusis can be reduced & potentially eliminated. However, the peculiarity of every case is obvious during treatment [11]. The peculiarity of every case of hyperacusis shows that despite the huge research on hyperacusis globally, there is a need to identify a local pattern, report, and document findings. The need to engage in hyperacusis research in Nigeria is pre-eminent and in essence, will help to build up the Nigerian research database on hyperacusis.

Conclusion

There is huge evidence of the paucity of research on hyperacusis in Nigeria. This should be a reveille to scholarly researchers to take a deep dive into the swirling pool of hyperacusis research. The onus rests on not just otorhinolaryngologists, but also on audivestibular medicine physicians audiologists , psychotherapists, mental health physicians, family physicians and others allied professionals to have a high index of suspicion and to report cases of hyperacusis to build up Nigerian research database.

Conflict of Interest

The Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

References

- Aazh H, Knipper M, Danesh AA, Cavanna AE, Andersson L, et al. (2018) Insights from the Third International Conference on Hyperacusis: Causes, Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Noise Health 20(95): 162-170.

- Sheldrake J, Diehl PU, Schaette R (2015) Audiometric Characteristics of Hyperacusis Patients. Frontiers in Neurology 6: 105.

- Diehl P, Schaette R (2015 ) Abnormal Auditory Gain in Hyperacusis: Investigation with a Computational Model. Frontiers in Neurology 6: 157.

- Tyler RS, Pienkowski M, Roncancio ER, Jun HJ, Brozoski T, et al. (2014) A review of hyperacusis and future directions: part I. Definitions and manifestations. American Journal of audiology 23(4): 402-419.

- Baguley DM (2003) Hyperacusis. J R Soc Med 96(12): 582-585.

- Sereda M (2003) Hyperacusis services in the United Kingdom: a survey of patient experiences.

- Aazh H, Landgrebe M, Danesh AA, Moore BC (2019) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Alleviating the Distress Caused by Tinnitus, Hyperacusis And Misophonia: Current Perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag 12: 991-1002.

- Sunny OD, Asoegwu CN, Abayomi SO (2012) Subjective Tinnitus and Its Association with Use of Earphones Among Students of The College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Nigeria. Int Tinnitus J 17(2): 169-172.

- Ahmed A (2016) Self-Reported Hearing-Related Complaints Among Dental Professionals: A Questionnaire-Based Survey. Borno Medical Journal 13(1): 228-238.

- Shabana MI, Selim MH, El Rafaie AMR, El Dassouky TM, Soliman RY (2011) Assessment of hyperacusis in Egyptian patients: Evaluation of the Arabic version of the Khalfa questionnaire 9(4).

- Schaette R (2014) Tinnitus in men, mice (as well as other rodents) and machines. Hear Res 311: 63-71.

- Fackrell K, Hoare DJ (2018) Scales and questionnaires for decreased sound tolerance. Baguley DM, Fagelson M (Eds.), Hyperacusis and Disorders of Sound Intolerance: Clinical and Research Perspectives. San Diego, Plural Publishing Inc, CA, USA.

- Jastreboff P, Hazell J (2004) Tinnitus retraining therapy: Implementing the Neurophysiological model. Psychology.

- Cox RM, Alexander GC, Taylor IM, Gray GA (1997) The contour test of loudness perception. Ear Hear 18(5): 388-400.

- Formby C, Gold SL, Keaser ML, Block KL, Haewley ML (2017) Secondary benefits from Tinnitus Retraining Therapy: Clinically significant increase in loudness discomfort level and expansion of the auditory dynamic range. Semin Hear 28(4): 227-260.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...