Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Efficacy of a Medical Device Based on Plant Extracts for the Symptomatic Treatment of Cough in Children and Adults. A Clinical Study Volume 7 - Issue 3

Gaetano Bottaro1, Benedetta Veruska Costanzo2, Filippo Palermo3, Tiziana Pecora4* and Vincenzo Perciavalle5

- 1Family Pediatrician, Catania, Italy

- 2General Practitioner, Catania, Italy

- 3Professor of Statistics, University of Catania, Italy

- 4Project Innovation Manager, Labomar SPA, Istrana (TV), Italy

- 5Professor of Physiology, University Kore of Enna, Italy

Received:October 23, 2021; Published: November 08, 2021

Corresponding author: Tiziana Pecora, Project Innovation Manager, Labomar SPA, Istrana (TV), Italy

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2021.07.000265

Abstract

Cough is one of the most common medical situations that leads to seek medical attention. The present study was carried out

to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of cough in adults and children of a sugar-free syrup containing glycerol

and extracts from roots of Althaea officinalis and from leaves of Plantago lanceolata (FTP 65 Cough syrup sugar free: Manufacturer

Labomar SPA). One hundred and twenty subjects (60 children and 60 adults) were recruited. Participants received for 7 days one

of the following dosage schedules:

a) Adult: “ Cough Syrup REF FTP 65” in single-dose containers of 10 ml, to be taken daily in 3 administrations

b) Children: “ Cough Syrup REF FTP 65” with a daily dosage of 10 ml/day for 2–6-year-old children, and of 20 ml/day, for

7–12-year-old children. The survey included three visits: a first visit (V0) of enrollment, a second visit (V1) after 3 days from the V0

and a third visit (V2) carried out after 7 days of therapy. The results of this study confirm the evidence that the medical device Cough

Syrup REF FTP 65 may represent a valid choice as a treatment for coughing in adults and children

Keywords: Cough; mucociliary clearance; Althaea officinalis; Plantago lanceolata; moisturizing film

Introduction

Cough is one of the most common medical situations that leads

to seek medical attention. It is an archaic reflex act that aims to

protect the respiratory tract from foreign materials. Despite its

frequency, there are still no objective methods to quantify the cough

whose assessment remains, therefore, eminently subjective. Due to

the vagueness of the nature of this symptom, together with a strong

impact on the quality of life, the absence of objective tools and

the possibility that it is expression of an insidious pathology, the

cough should be considered and cured as a major problem until a

harmless etiology is identified. The cough is a reflex act, essentially

uncontrollable, capable to facilitate the mucociliary clearance and

to determine the removal of excess secretions from the airways. The

mucociliary clearance depends on the presence on inner surface of

the respiratory tree, from the trachea to the terminal bronchioles,

of a ciliated respiratory epithelium. Every single epithelial cell has

about 200 cilia (each cilium is about 7 μm in length) that protrude

towards the lumen and that constantly beat at a speed of 10-20 Hz.

The cilia are surrounded by a layer of periciliary fluid formed

by a deeper, very fluid layer, in turn dominated by a mucous

layer, together forming the epithelial lining fluid that, in addition

to keeping the epithelium moist, traps the particulate material

that has penetrated the respiratory tract. The cilia beat with a

coordinated movement directed towards the pharynx where the

transported mucus is swallowed or eliminated with the cough. An

effective mucociliary clearance depends on a number of factors,

including the number of cilia, their structure, the frequency with which they oscillate, and the quality of the mucus produced which

must be maintained at a correct humidity, temperature and acidity.

The cilia must be able to move freely in the layer of periciliar fluid

and when this is compromised, the mucus cannot be correctly

removed from the respiratory tract [1]. The cough reflex act

is characterized by the simultaneous closure of the glottis and

activation of an expiratory act with the resulting increase in the

intrathoracic pressure that can even exceed 300 mm Hg. The strong

increase in intrapulmonary pressure causes the violent expulsion

of the airway contents through the glottis into the pharyngeal

space and, therefore, out of the respiratory system. Due to the high

intensity of this process, in which the velocity of the expired air

can exceed 800 km/h, mucous secretions are detached from the

airway and expelled. In normal conditions, the cough is a protective

mechanism, but under certain circumstances can occur alterations

in the system’s physiology capable to generate situations that are

often unfavorable and exasperating for the patient.

The cough reflex is initiated by the activation of sensory

receptors located mainly, but not exclusively, in the pharynx, in

the larynx and along the entire tracheobronchial tree. Some of

these receptors are activated by chemical stimuli while others by

mechanical ones. Chemical type receptors, located mainly in the

respiratory tract, are activated by acids, heat and capsaicin-like

molecules that act on capsaicin type-1 receptors. The mechanical

type receptors are located not only in the respiratory tract but also

in the in the paranasal sinuses, eardrum, external auditory canal,

in pleura, pericardium, diaphragm, and stomach [2]. The different

types of sensory receptors are connected to the CNS through

afferent fibers that travel in the Vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) to the

respiratory centers located in the brainstem. The exact location of

the hypothetical cough center is not known, but it is likely that the

cough, rather than the effect of the activation of a single structure,

is the consequence of the modulation of the different respiratory

centers located in the brainstem [3]. Traditionally, the cough’s

mechanism is divided into 3 successive phases: the inspiratory

phase, the compression phase and the expiratory phase. The

first has the task of making a sufficient amount of air enter the

lung to produce an efficient cough. The compression phase is

characterized by the closure of the glottis and the simultaneous

contraction of the expiratory musculature that leads to a strong

increase in intrapulmonary pressure. Finally, the expiratory phase

is characterized by a rapid opening of the glottis resulting in an

explosive outflow of air. At the end of the exhalation, an inspiration

usually occurs to compensate for the developed hypoxia.

As mentioned above, in addition to the use of pharmacological

treatments based on antitussives, antihistamines or fluidizers,

cough can be treated by using plant extracts rich in polysaccharides.

In fact, they, with a purely mechanical action, form a moisturizing

and protective film [4] with a barrier effect that, on the one

hand, limits contact with irritating agents and, on the other one,

moisturizes the mucus so favoring a physiological expectoration.

The present medical device is a sugar-free syrup containing glycerol

and polysaccharide-rich aqueous extracts from roots of Althaea

officinalis and from leaves of Plantago lanceolata. Althaea officinalis

is traditionally used for the treatment of cough and inflammation of

the upper respiratory tract. Its roots are known to contain relatively

high mucilage content that makes this herb excellent demulcent,

emollient, expectorant [5]. Plantago lanceolata is indicated for

the treatment of cough for the presence of components such as

mucilages with an emollient and soothing action [6]. Glycerol or

glycerine is an ingredient found in many cough preparations for

its lubricant, emollient, and humectant properties [7]. The aim of

the present study was to confirm the efficacy and tolerability of the

syrup in the treatment of cough in adults and children from 2 years

of age.

Materials and Methods

Study design

In the period between March and May 2019, a multicenter postmarketing

study was carried out. The study was conducted at two

primary care clinics, the first of general practitioner and the second

of family pediatrician, involving: adults, males and females, with

an age between 18 and 65 years, and children, male and female,

with an ages between 2 and 12 years. A total of 120 subjects were

recruited: 60 children and 60 adults. The used product was Cough

Syrup REF FTP 65 (Labomar SPA, Istrana , TV, Italy) a medical device

already available on the European market under different brand

names and composed of extract of Plantago lanceolata, extract

of Althaea officinalis, vegetable glycerin, thyme extract, sorbitol,

water, xanthan gum, natural flavors, citric acid, potassium sorbate,

sugar-free and gluten-free. The experimental protocol “Study Code:

SFT2018” was approved by the Ethical Committee “Catania 2”, in

the session of 11/13/2018. All adult subjects signed the Informed

Consent approved by the Ethics Committee, while for children the

Informed Consent was signed by both parents and children over

5-year-old. After Informed Consent and basic evaluations, patients,

considered suitable for enrollment in the study, received one of the

following dosage schedules according to the instructions for use of

manufacturer:

a) Adult: “Cough Syrup REF FTP 65” in single-dose containers of

10 ml, to be taken daily in 3 administrations.

b) Children: “Cough Syrup REF FTP 65” with a daily dosage of

10 ml/day for 2–6-year-old children, and of 20 ml/day, for

7–12-year-old children.

The overall duration of the survey for each subject was seven

days.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects were admitted to the survey:

a. Females and males’ adults, suffering from cough associated

with sore throat or upper respiratory tract infections.

b. Females and males’ children, suffering from cough also

associated with sore throat or upper respiratory tract

infections

Exclusion criteria

Subjects were not included in the survey if:

a. Presenting contraindications indicated in the instructions for

use of the product “ Cough Syrup REF FTP 65”;

b. Presenting presumed or ascertained hypersensitivity to one or

more of the ingredients present in the formulation

c. Having a history of anaphylaxis or allergic reactions in general

or serious food intolerances, which the doctor may deem

relevant for inclusion in the study with concomitant conditions

that do not guarantee participation / participation in the study

according to the investigator’s opinion.

d. Were children affected by chronic pathologies with serious

respiratory compromises (cystic fibrosis, Spinal muscular

atrophy, dystrophies, cerebral palsy or oncological

pathologies).

e. Were adults with an overly complicated clinical picture for

which the investigating doctor believes that participation in

the study may be in some way harmful.

f. Were adults and children already in therapy with other

preparations for cough treatment in acute respiratory

infections.

Concomitant therapies

The subject had to follow an adequate diet; subjects in therapy with other cough preparations including cough suppressants and mucolytics were not included in the study. Any assumption of concurrent permitted and non-permitted drugs was reported in the Data Collection Form (DCF) and used for the final evaluation.

Study procedures

The survey included three visits. A first visit (V0) of enrollment,

a second visit (V1) carried out after 3 days from the V0 and a third

visit (V2) carried out after 7 days of therapy, i.e., at the end of the

study therapy.

V0 (enrollment): first enrollment visits and compilation of the

SRD:

a. explanation of the investigation to the subject if adult or to the

parent / legal representative and obtaining written Informed

Consent before each investigation procedure.

b. medical history and verification of inclusion and exclusion

criteria and clinical evaluation.

c. evaluation of the cough by using a questionnaire.

d. assessment of associated symptoms:

e. for adults: general conditions (poor, satisfactory good), fatigue,

vomiting, hoarseness, difficulty breathing, chest pain, vertigo

and urine leakage; all these parameters were evaluated in

mild, moderate, severe.

f. for children: general conditions (poor, satisfactory good),

fever (Celsius degrees, °C), headache, vomiting, hoarseness,

stuffy nose, ear pain, assessed in mild, moderate, severe, and

respiratory sounds (wheezes, rhonchi, and rales).

g. assessment of psychophysical well-being for adults, with

questions as: do you feel depressed? Do you feel irritated? Do

you feel tired? Do you consider yourself sick?

h. evaluation of daily activities such as: loss of school days, loss

of days of work of parents, reduction of appetite and sense of

discomfort.

i. any concomitant therapy and the type of drug used were

recorded.

j. setting of therapy with “ Cough Syrup REF FTP 65” and delivery

of product.

k. programming of visit 1 (V1).

V1: second visit:

a) review of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

b) evaluation of the symptom cough based on the questionnaire.

c) clinical evaluation and associated symptoms.

d) evaluation of the parameters of psychophysical wellbeing for

adults and those of daily activities for children.

e) registration of any adverse effects.

V2: final visit, conclusion of the study

a) review of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

b) evaluation of the symptom cough based on the questionnaire.

c) assessment of the patient’s general condition.

d) evaluation of efficacy, tolerability and compliance of the

medical device.

e) assessment of patient satisfaction.

f) evaluation of the parameters of psychophysical wellbeing for

adults and those of daily activities for children.

g) assessment of any adverse effects incurred.

h) completion of the end of study procedures.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was the evaluation of the efficacy of the medical device Cough Syrup REF FTP 65 to reduce the symptom cough in adults and children with acute respiratory diseases. To assess the cough’s intensity and its impact on the patient’s daily life we used a questionnaire taken from validated cough measurement instruments such as cough scales (Table 1). The result was given by the variation from baseline (V0) to the intermediate visit (V1) and at the end of the treatment (V2). The secondary endpoints included the evaluation of the clinical status, the evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of the medical device Cough Syrup REF FTP 65 obtained from the variation from baseline (V0) to the intermediate visit (V1) and at the end of treatment (V2).

Data analysis

The sample used was considered adequate for the purpose of the study, namely: observation and description of the efficacy and safety characteristics of the product under study in the postmarketing follow-up. The intention-to-treat population was used for the analysis of the raw data. Comparisons between the groups, openly treated, were of a descriptive nature and data were reported in terms of means and standard deviations (SD) for quantitative variables and in terms of absolute frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. To detect significant differences in changes in primary and secondary efficacy endpoints from baseline (V0) to the end of treatment (V2) the exact Fisher test, Chi square test with Yates’s correction, McNemar test and Mann-Witney test were used.

Results

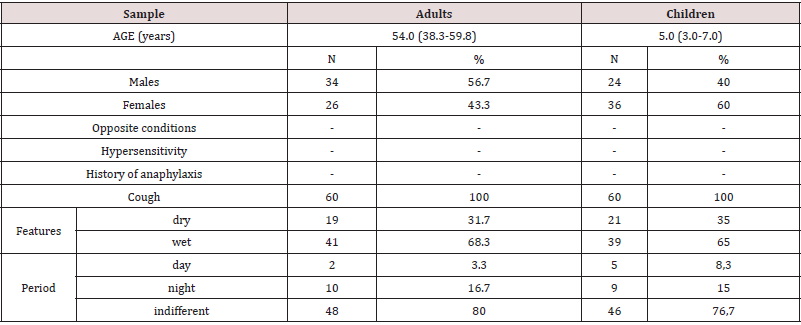

Children

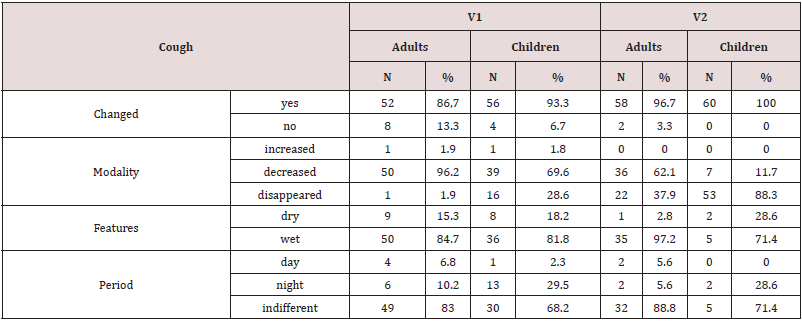

The 60 children had a median age of 5 years (range 3-7 years), 24 were males (40%) and 36 females (60%); all had coughs and had no contraindications to the use of medical device Cough Syrup REF FTP 65, nor conditions that hindered the taking. The cough was dry in 21 (35%) and wet in 39 (65%) children. Only 5 (8.3%) children had daytime cough, 9 (15%) had nocturnal cough, all the other 46 (76.7%) children had either daytime or night cough. Concerning the associated symptoms, at the time of diagnosis (V0) 40 children (66.7%) had poor general conditions, 17 (28.3%) satisfactory conditions, 3 (5%) very poor conditions and non-good conditions. Forty-three children (71.7%) had fever with a median value of 38 °C (38 - 38.5 °C); 51 children (64.7%) had headaches, most of them mild (33, 64.7%), 18 moderate (35.3%); 6 children (10%) had mild vomiting. Fifty-two children (86.7%) had hoarseness, 36 (69.2%) moderate, 13 (25%) mild and only 3 (5.8%) severe. Fiftythree children (88.3%) had coryza, out of which 11 (20.8%) mild, 38 (71.7%) moderate, 4 (7.5%) severe. Eight children (13.3%) had ear pain, out of which the majority were mild (6, 75%), 1 moderate (12.5%) and 1 severe (12.5%). Finally, 54 children (90%) had positive respiratory sounds, 7 children (13%) had wheezing, 31 (57.4%) Ronchi and 16 (29.6%) rales (Table 2).

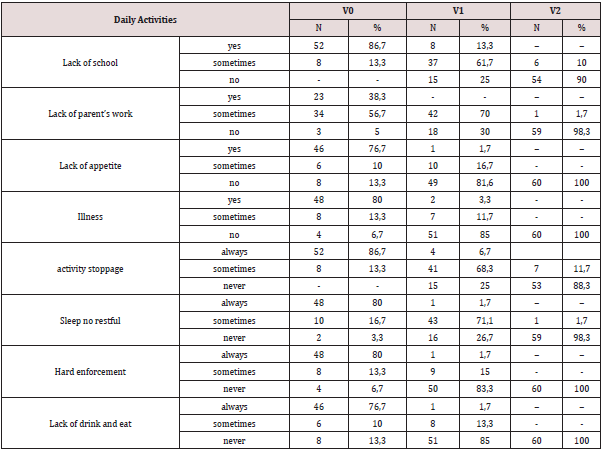

As regards the influence on activities, at the time of diagnosis only 4 children (6.7%) declared that cough did not affect their activities while 56 children (93.3%) sometimes felt compelled to interrupt them. Fifty-two children (86.7%) stated that sometimes they did not have a restful sleep, 2 (3.3%) always, 6 (10%) never; 35 children (48.3%) stated that sometimes he had difficulty concentrating, 10 (16.7%) always, 15 (25%) never. Thirty-five children (58.3%) declared that, when sick, they always stopped eating, 15 (25%) sometimes, 10 (16.7%) ever (Table 3). As for daily activities, at the time of diagnosis 52 children (86.7%) had constant loss of school days and 8 (13.3%) only sometimes. The parents of 23 children had always lost working days, 34 (56.7%) sometimes, only the parents of 3 children (5%) had not lost working days; 46 children (76.7%) had always lost their appetite, 6 (10%) sometimes, 7 (13.3%) never; finally, 48 children (80%) always had a sense of malaise, 8 (13.3%) sometimes, 4 (6.7%) never.

At the time of the first visit, in addition to the product being

tested, 29 children (47.1%) received another drug, most often

salbutamol (13 children, 44.8%), 6 children (10%) received an

antibiotic, 6 children (20.7%) the combination paracetamolchlorphenamine,

1 child (3.4%) beclomethasone for inhalation,

1 child (3.4%) cetirizine and, finally, 3 children (10.3%) other

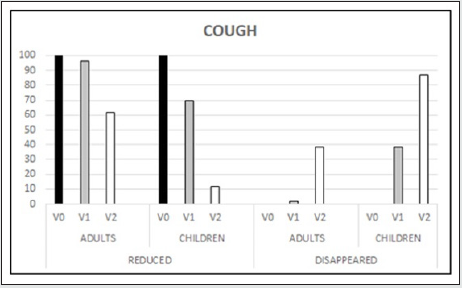

preparations for cough. The endpoints evaluation showed that

already at V1, after only 3 days of therapy, 56 children (93.3%)

showed a change in cough and only 4 (6.7%) had no change; those

in which the coughing had changed, 39 children (69.6%) had decrease, in 16 (28.6%) cough disappeared and only in 1 (1.8%)

cough increased. Concerning the characteristics, the cough was

kept wet in 36 children (81.8%) and dry in 8 (18.2 &); the cough

remained both diurnal and nocturnal in 30 (68.2%), while 13

(29.5%) still presented it nocturnal and only 1 (2.3%) diurnal. At the

final visit all the children (100%) had modified cough, in 7 (11.7%)

cough decreased, while in the other 53 (88.3%) cough disappeared.

The characteristics had remained the same: predominantly wet

(71.4%) and indifferent (71.4%). As for the associated symptoms,

these showed, already at V1, an improving trend, with the exception

of the general conditions that remained unchanged with respect to

the initial visit. On the contrary, fever persisted in only 3 children

(5%), a mild headache was present only in 12 (20%), vomiting only

in 1 (1.7%), while hoarseness persisted in 15 (25 %). In 19 children

(31.7%) persisted the coryza, out of which 16 (84.2) was mild; in 3

(5%) persisted ear pain and in 12 (20 %) respiratory sounds, more

often ronchi (10, 83.4%). At V2 the improvement was evident with

good general conditions in all 60 children (100%); only 1 (1.7%)

persisted headache, none vomited, only 2 (3.3%) had hoarseness,

2 (2.2%) coryza, none had more ear pain, and none had abnormal

respiratory sounds.

As for the influence on daily activities, already at V1 only 4

(6.7%) and none at V2, had been forced to interrupt them. Fortyone

(68.3%) were sometimes at V1 and 7 (11.7%) at V2, 15 (25%)

and 53 (88.3%) at V2 were no longer; only 1 (1.7%) and none at

V2, had no restful sleep, 43 (71.7%) had sometimes not and 16

(26.7%) had never at V1 and only 1 (1.7%) at V2, mind the other

59 (98.3%) never. Fifty children (83.7%) at V1 and all 60 (100%)

at V2 had no more difficulty in concentrating; only 1 (1.7%) always

had it and 9 (15%) sometimes at V1. Finally, already 51 children

(85%) had no more difficulties in eating and drinking in V1 and

15 (25%) in V2, 10 (16.7%) and 45 (76.7%) in V2 were no more;

11 subjects (6.7%) and only 1 (1.7%) always had difficulties and 8

(13.3%) sometimes, in V2 nobody had any more. As far as the daily

functions, already at V1 were concerned, only 8 (13.3%) and none

at V2, had lost their schooling, 37 (61.7%) had lost it sometimes

at V1 and 6 (10%) at V2, 15 (25%) and 54 (90%) at V2 had not

lost it anymore. In 42 children (70%) at V1 and only 1 (1.7%) at

V2, the parents had sometimes lost their job, while 18 (30%) at V1

and 59 (98.3%) at V2, had not lost it anymore. Only 1 child (1.7%)

and none at V2 had a reduction in appetite, 10 children (16.7%) at

V1 and none at V2 had sometimes a reduction in appetite, while

49 children (81.6%) at V1 and all (100%) at V2 had no reduction

in appetite. Finally, only 2 children (3.3%) at V1 and none at V2

had a reduction in appetite, 7 (11.7%) at V1 and none at V2 had

sometimes a reduction in appetite, 51 children (85%) at V1 and

none at V2 had a reduction in appetite.

Nineteen children out of the initial 29 had maintained the

associated drug therapy, as was logical to think, but at V2 still 10

children were taking an associated drug.

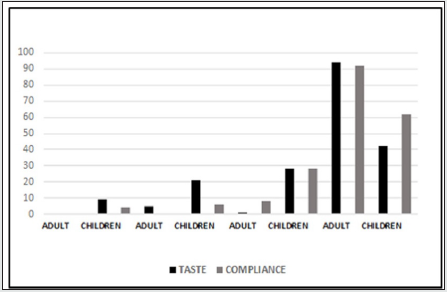

In terms of efficacy, 53 children (88.3%) assessed it as good at

V1, 2 children (3.3%) as satisfactory and 5 (8.4&) as excellent, while

at V2 all 60 children (100%) assessed it as excellent. Tolerability

was considered good by 59 children (98.3%) already at V1, only 1

(1.7%) satisfactory, while at V2, all 60 children (100%) considered

it very good. Only one child (1.7%) was agitated when taking the

syrup, which lasted a few days during the therapy, which did not

need to be suspended, and disappeared immediately after the

suspension of the therapy. All subjects took all the doses (8 to V1

and 14 to V2) and followed the therapy. 25 children (41.7%) found

the taste of the syrup very good, 17 (28.3%) good, 13 (21.7%)

bad and 5 (8.3%) very bad; 38 children (63.3%) considered the

syrup very easy to swallow, 17 (28.3%) easy, 3 (5.1%) difficult, 2

(3.3%) very difficult. The statistical analysis showed high statistical

significance (chi2 p<0.001) for all the variables already considered

at the intermediate visit and especially at the final visit. The

following associated symptoms also showed a statistically highly

significant reduction (p<0.001) in McNamar’s test at both V1 and

V2: fever, headache, hoarseness, coryza and chest pain; at V2 the

reduction was statistically significant for vomiting (p<0.05) and

otalgia (p<0.01) because they already started from a small number

of subjects (Figures 1 & 2).

Adults

The 60 adults had a median age of 54 years (range 38-60 years),

34 were males (57%) and 26 females (43%), all had coughs and

had neither contraindications to the preparation nor conditions

that hindered its intake. The cough was dry in 19 subjects (32%),

wet in 41 (68%) subjects. Only 2 (3%) adults had daytime cough,

10 (17%) had nighttime cough, all the other 48 (80%) had both

daytime and nighttime cough. Concerning the associated symptoms,

at the time of diagnosis 31 (51.7%) had poor general conditions, 24

(40%) satisfactory, 1 (1.7%) poor and 4 (6.6%) good. Fifty-three

adults (88.3%) experienced fatigue, although the majority (39,

73.6%) experienced mild fatigue; 42 adults (70%) suffered from

headache, the majority of which were mild (36, 85.7%), 6 subjects

(10%) had vomiting and 9 (15%) hoarseness. Forty-two subjects

(70%) had difficulty breathing, of which 22 (52.4%) were mild;

40 subjects (66.7%) had chest pain, the majority of which were

mild (25, 62.6%); only 3 subjects (5%) had dizziness and 6 (10%)

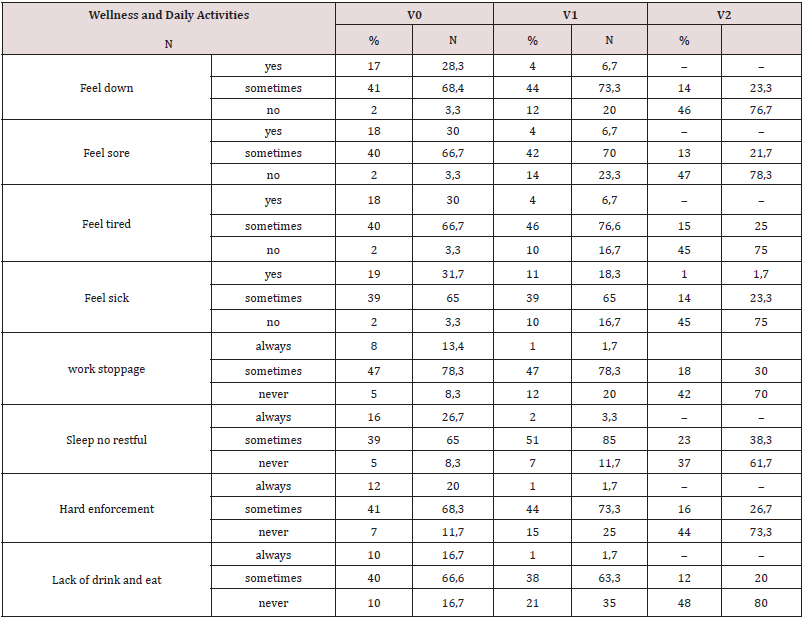

slight loss of urine (Table 2). As regards the influence on physical

well-being, at the time of diagnosis 41 subjects (68.3%) sometimes

felt depressed, 17 (28.3%) always felt depressed, 2 (3.3%) never.

Forty subjects (66.7%) sometimes felt irritated, 18 (30%) always, 2

(3.3%) never; 40 subjects (66.7%) sometimes felt tired, 18 (30%)

always, 2 (3.3%) never; 39 subjects (65%) sometimes felt sick, 19

(31.7%) always, 2 (3.3%) never.

Concerning daily activities, at the time of diagnosis 47 subjects

(78.3%) sometimes interrupted their work, 8 (13.4%) always, 5

(8.3%) never; 39 subjects (65%) had sometimes no restful sleep,

16 (26.7%) always, 5 (8.3%) never. Forty-one subjects (68.3%)

sometimes had difficulty concentrating, 12 (20%) always, 7 (11.7%)

never; finally, 40 subjects (66.7%) sometimes stopped drinking and

eating, 10 (16.7%) always, 10 (16.7%) never (Table 4). At the first

visit and in conjunction with the investigational product 21 subjects

(35%) received another drug, more often an antibiotic (8, 13.3%),

than a steroid (6, 10%), someone an antihistamine. The evaluation

of endpoints showed that already at V1, after 3 days of therapy, 52

subjects (86.7%) showed a modification of the cough and 8 (13.3%)

a stationarity; of those in which it was modified, 50 (96.2%) had

shown a decrease, 1 (1.9%) disappeared and 1 (1.9%) increased.

As far as its characteristics were concerned, the cough remained

wet (84.7%) and indifferent between day and night (83%). At the

final visit the same trend was maintained with 58 (96.7%) subjects

in which it had changed and of these 36 (62.1%) showed a decrease

and 22 (37.9%) disappeared. The characteristics had remained the

same: mainly wet (97.2%) and indifferent (88.8%).

Regarding the associated symptoms, they showed, already at

V1, an improving trend. General conditions were satisfactory in

43 (71.7%) and good in 13 (21.7%), headache was present only

in 19 (31.7%), vomiting and hoarseness only in 3 (5%), difficulty

in breathing persisted in 34 (56.7%) subjects and chest pain in 25

(41.7%), no one had dizziness and only 2 (3.3%) loss of urine. At V2

the improvement was evident with good general conditions in 55

(91.7%), only 4 (6.7%) had headaches, no one vomited, only 3 (5%)

had hoarseness, 16 (23.7%) had difficulty breathing, 3 (5%) chest

pain and only 1 (1.7%) dizziness.

As for the influence on physical well-being, already at V1 only

4 (6.7%) and none at V2, still felt depressed, 44 (73.3%) were

sometimes depressed at V1 and 14 (23.3%) at V2, 12 (20%) and

46 (76.7%) at V2 were no longer. Only 4 (6.7%) and none at V2,

still felt irritated, 42 (70%) were sometimes at V1 and 13 (21.7%)

at V2, 14 (23.3%) and 47 (78.3%) at V2 were no longer irritated.

Only 4 (6.7%) and none at V2, still felt tired, 46 (76.6%) were

sometimes at V1 and 15 (25%) at V2, 10 (16.7%) and 45 (76.7%)

at V2 were no longer tired. Eleven subjects (6.7%) and only 1

(1.7%) at V2, still felt sick, 39 (65%) were sometimes at V1 and

14 (23.3%) at V2, 10 (16.7%) and 45 (75%) were no longer sick.

Regarding daily activities, already at V1, only 1 (1.7%) and none

at V2, had interrupted work, 47 (78.3%) had sometimes done so

at V1 and 18 (30%) at V2, 12 (20%) and 42 (70%) at V2 had not

interrupted it anymore. Only 2 participants (3.3%) and none at V2

had a restful sleep, 51 (85%) had sometimes at V1 and 23 (38.3%)

at V2, 7 (11.7%) and 37 (61.7%) at V2 had a restful sleep. Only one

participant (1.7%) and none at V2, had difficulty concentrating, 44

(73.3%) had it sometimes at V1 and 16 (26.7%) at V2, 15 (25%)

and 44 (73.3%) at V2 had it no more. Finally, only 1 subject (1.7%)

and none at V2, had stopped drinking and eating, 38 (63.3%) had it

sometimes at V1 and 12 (20%) at V2, 21 (35%) and 48 (80%) had

it no more.

Seventeen subjects out of the initial 21 maintained the

associated drug therapy, as was logical to think, but at V2 only 5

were still taking an associated drug. Concerning effectiveness of

treatment, 30 subjects (50%) assessed it as good at V1 and 6 (10%)

at V2, 27 (45%) assessed it as excellent at V1 and 53 (88.3%) at V2,

only 2 (3.3%) at V1 and 1 (1.7%) at V2 considered it satisfactory

and 1 subject (1.7%) at V1 considered it poor. Tolerability was

considered good by 14 subjects (23.3%) to V1 and 2 (3.3%) to V2,

excellent by 45 subjects (75%) to V1 and 56 subjects (93.4%) to V2,

only 1 (1.7%) to V1 and 2 (3.3%) considered it poor. All subjects

took all the doses (9 to V1 and 20 to V2) and followed the therapy.

57 subjects (95%) found the taste of the syrup very good, 1 (1.7%)

good and only 2 (3.3%) bad; 56 subjects (93.3%) considered

it very easy to swallow the syrup and 4 (6.7%) easy, nobody

found it difficult. The statistical analysis showed high statistical

significance (chi2 p<0.001) for all the variables considered already

at the intermediate visit and especially at the final visit. Also, the

associated symptoms showed statistically significant difference

to McNemar’s test already at V1 headache (p<0.001) and chest

pain (p<0.01), but a bit all at V2: headache (p<0.001), vomiting

(p<0.01), difficulty breathing (p<0.001), chest pain (p<0.001) and

loss of urine (p<0.01). Only hoarseness and dizziness did not show

significant differences, probably because they already started from

a small number of subjects (Figures 1 & 2).

Discussion

Coughing at any age has to be dealt with different approaches. It is always necessary to go back to the initial cause and remove it, either from infectious causes, identifying the agent in question and starting the specific therapy, you know allergic or from irritating substances by removing the cause (allergens, smoke, pollutants, etc.). However, at the same time, it is essential to improve the symptom, to improve the quality of life and bring daily benefits. If it can be useful to alleviate the course of an annoying cough that lasts a few days, it is always necessary to intervene when the cough is caused by an identified etiological agent [8]. A specific treatment of the cough symptom is of great importance both for the adult, because it improves the mood, the perception of health and the evaluation of one’s own state of health, and in the child, because seeing his or her own little cough creates fear and discomfort in the whole family. In any case, if the cough does not pass within a few days, it is necessary to initiate more specific diagnostic investigations to make a precise diagnosis. The treatment of the symptom cough has always relied on sedatives, i.e., substances that, by suppressing the cough reflex, prevent coughing [9]. Unfortunately, some act on the central nervous system and derive from morphine (codeine, etc.), others with central action do not derive from morphine (dextromethorphan, cloperastine, etc.), others are peripheral sedatives (levodropropizine, etc.), acting on sensory fibres afferent to the center of the cough. Many of these cough sedatives cannot be used in children under 2 years of age and in any case both in older children and adults, they are all of dubious efficacy and have presented, depending on the different points of action, important side effects, mainly represented by restlessness and drowsiness [10-15]. Banned expectorant syrups, never indicated in children under 12 years of age and working badly in adults with few exceptions [16], the alternative is to use natural preparations. Most of the preparations did not fail the most important test of effectiveness and showed to reduce the discomfort of coughing. The active ingredients used for these preparations have been many over time, starting with thyme, ivy, etc., all plants that nature makes available to us to soothe the problems of the first airways and in cases of coughing. In this context is inserted the medical device object of the present clinical investigation which, thanks to its components (glycerol, marshmallow and plantain), has a calming action on the irritation and protective action of the respiratory tract mucosa. The results of the present study showed that the medical device used by us is highly effective in improving the cough symptom, even after only 3 days of therapy in the adult (86.7%) and after 4 days of therapy in the child (93.3%). In addition to the change of cough all symptoms improve after the first days of therapy and this allows a rapid resumption of daily functions, work activities and overall perception of health status. The combined action of Alhtea, Plantago and glycerol has allowed our device to act completely on all kind of cough (wet, dry) presented by both adults and children, resulting effective. It is worth noting that a recent review confirmed the efficacy of Alhtea officinalis extracts alone in treatment of dry cough, while in combination with other extracts improved all kinds of cough [17]. The cough is a symptom that is very annoying to the patient and his family, since it is linked to diseases important for severity and danger, its improvement is therefore able to determine serenity and tranquility important for a good course of the disease. In any case, a product, be it a drug or a device, must be not only effective but also well tolerated and agreeable. In the present study, we have noticed differences between adults and children. Adults consider Cough Syrup REF FTP 65 almost unanimously good/very good (97%), children a little less (70%). Only one child presented a side effect (agitation) which, in any case, was mild and did not require therapy to be discontinued.

Conclusions

The results of this study confirm the evidence that the medical device Cough Syrup REF FTP 65, with its content in natural functional components and its efficacy and safety profile, may represent a valid choice as a treatment for coughing in adults and children. It allows reducing the traditional therapy, with a faster return to school and to normal, working life of adults. In addition, the good taste and ease of administration of the product make it practical and easily accepted.

Statement of Ethi

All procedures in this study were performed in accordance with the of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ethical Committee “Catania 2” of Catania (Italy).

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study received no financial support

Author Contributions

Vincenzo Perciavalle is the corresponding authors of this article. All authors planned and designed the study; Gaetano Bottaro and Benedetta Veruska Costanzo performed the experiment. Tiziana Percora and Filippo Palermo are responsible for data collection. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the analysis. Vincenzo Perciavalle wrote the paper, and all authors critically revised the manuscript.

References

- Stanke F (2015) The contribution of the airway epithelial cell to host defense. Mediators of Inflammation 2015: 463016.

- Ebihara S, Izukura H, Miyagi M, Okuni I, Sekiya H, Ebihara T (2016) Chemical senses affecting cough and swallowing. Current Pharmaceutical Design 22: 2285-2289.

- Mutolo D (2019) Brainstem mechanisms underlying the cough reflex and its regulation. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 243: 60-76.

- Franz G (1989) Polysaccharides in Pharmacy: current applications and future concepts. Planta Medica 55: 493-497.

- Sutovská M, Nosálová G, Sutovský J, Franová S, Prisenznáková L, Capek P (2009) Possible mechanisms of dose-dependent cough suppressive effect of Althaea officinalis rhamnogalacturonan in guinea pigs test system. nternational Journal of Biological Macromolecules 45: 27-32.

- Wegener T, Kraft K (1999) Plantain (Plantago lanceolata L.): anti-inflammatory action in upper respiratory tract infections [Article in German] Wiener klinische Wochenschrift 14: 211-216.

- Eccles R, Mallefet P (2017) Soothing properties of glycerol in cough syrups for acute cough due to common cold. Pharmacy (Basel) 5(1) p: 4.

- Kaplan AG (2019) Chronic cough in adults: make the diagnosis and make a difference. Pulmonary Therapy 5: 11-21.

- Wang K, Bettiol S, Thompson MJ, Roberts NW, Perera R, Heneghan CJ, Harnden A (2014) Symptomatic treatment of the cough in whooping cough. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 22(9): CD003257.

- Kurth W (1978) Secure therapeutic effectiveness of the traditional antitussive agent Mintetten in a double-blind study [Gesicherte therapeutische wirksamkeit des traditionellen antitussivums mintetten im oppelblindversuch]. Medizinische Welt 29: 1906–1909.

- Banderali G, Riva E, Fiocchi A, Cordaro CI, Giovannin M (1995) Efficacy and tolerability of levodropropizine and dropropizine in children with non-productive cough. Journal of International Medical Research 23: 175–183.

- Freestone C, Eccles R (1997) Assessment of the antitussive efficacy of codeine in cough associated with common cold. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 49: 1045–1049.

- Gunn VL, Taha SH, Liebelt EL, Serwint JR (2001) Toxicity of over-the-counter cough and cold medications. Pediatrics 108(3): e52.

- Kelly LF (2004) Pediatric cough and cold preparations. Pediatrics in Review 25: 115–123.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005) Infant death associated with cough and cold medications - two states. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 56: 1–4.

- Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T (2014) Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in community settings. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews (11): CD008131.

- Mahboubi M (2020) Marsh Mallow (Althaea officinalis L.) and its potency in the treatment of cough. Complementary Medicine Research 27(3): 174-183.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...