Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Complication Associated with Hearing Aid Fitting among Adults Volume 8 - Issue 4

Akinyode Gbenga Akinyemi*

- Master of Clinical Audiology and Hearing Therapy, School of Advanced Education, Research and Accreditation, Isabel I University, Spain

Received: July 15, 2022; Published: July 27, 2022

Corresponding author: Akinyode Gbenga Akinyemi, Master of Clinical Audiology and Hearing Therapy, School of Advanced Education, Research and Accreditation, Isabel I University, Spain

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2022.08.000293

Abstract

Objective: To identify and as well as gather perspectives of hearing aid users with regard to the main difficulties that may arise following hearing aid fitting among adults across states and to address the main problems.

Design: Descriptive and psychometric research design type of the survey. Development of the HAUQ and HASKI-self and investigation of its psychometric properties in a prospective convenience cohort of 250 adult hearing aid users, ranging in age from 18 to 99 years of age (M = 151 F = 99), 60.4% male, 39.6% female, recruited from different regions or states in Nigeria.

Results: The majority of participants (87%) indicated that they were experiencing at least one of the hearing aid problems included on the survey. The prevalence of individual problems ranged from 2.8% to 87.25%. The most reported problems or difficulty in this study were related to hearing aid management (insertion and removal), hearing aid maintenance and sound quality (hearing aid feedback/whistling, unbearable loud noises, own voice sound/quality), and hearing aid knowledge or lack of information and training. Participants who reported experiencing a greater number of hearing aid problems also reported lower levels of hearing aid benefit, and satisfaction with their hearing aids.

Conclusions: Problems relating to hearing aid fitting and management were most often considered to have the greatest impact on hearing aid success. The majority of hearing aid users experience difficulty with their hearing aids. The magnitude and diversity of hearing aid problems identified in this study highlight the ongoing difficulty that hearing aid users face and suggest that current processes for hearing aid fitting can be upgraded. These results can be used to inform clinicians on areas that need more emphasis in the fitting process and help identify those clients who are at risk for hearing aid non-users or do not wear their hearing aids as much as they would like to and provide additional support to them, and as well improved hearing aid outcomes among adults.

Keywords: Hearing loss; adult; hearing aid; hearing aid fitting; hearing aid user; hearing aid complication

Introduction

Hearing loss is the fourth highest cause of disability globally, with an estimated annual cost of over 750 billion dollars. Hearing loss in adults is encountered in all medical settings and frequently influences medical encounters. This disorder constitutes a substantial burden on the adult population in the world. Approximately half of people in their seventh decade (60 to 69 years of age) and 80% who are 85 years of age or older have hearing loss that is severe enough to affect daily communication, yet screening for hearing loss is not routine, and treatments are often inaccessible because of the high cost or perceived ineffectiveness [1]. The highest prevalence of hearing loss is observed in the Central/Eastern Europe & Central Asia region (8.36%), followed closely by South Asia (7.37%) and the Asia Pacific (6.90%) [2]. The greatest percentage of adults with Hearing loss was in the South Asian, Eastern Europe and Central Asian regions [3]. The sense of hearing provides a background, which gives a feeling of security and participation in life. It plays a critical role in the development of speech and language and in monitoring one’s speech. There are many risk factors for hearing loss; these include exposure to loud sounds (both in occupational settings and recreational settings), chronic ear infections, and ototoxicity (particularly iatrogenic ototoxicity). The burden of avoidable causes of hearing loss can be reduced by addressing the risk factors.

The primary clinical management intervention for people with hearing loss is hearing aids but not all people with some measurable form of hearing loss are candidates for hearing aids. Intervention for hearing loss includes devices that amplify sound to help overcome hair cell deterioration and improve listening, including hearing aids and cochlear implants, which are both forms of sensory management; hearing assistive technology systems, which are devices that help a person communicate better in daily situations; and aural rehabilitation, which focuses on a person learning to adjust and cope with their hearing loss. Specifically, issues relating to physical fit, hearing aid handling (such as difficulty inserting batteries), performance issues (such as sound quality or inability to reduce background noise) and complaints regarding ongoing maintenance requirements (such as cleaning and basic repairs) have been reported [4]. Aural rehabilitation is not part of a standard Hearing Aid fitting in Nigeria. Despite the negative consequences associated with hearing loss, only one out of five people who could benefit from a hearing aid actually wears one [3]. Kochkin [5] surveyed adults with self-reported hearing loss who did not use hearing aids. Among the many reasons or complication reported for not using hearing aids after fitting was the belief by individuals that their hearing loss was too mild for hearing aids.

Brooks [6] also found that people who were the least distressed by their hearing loss and reported that they neither wanted nor needed a hearing aid had the lowest rates hearing aid use when measured after fitting. Although the cost of the devices, typically $1,400 to $2,200, is probably a factor, other deterrents to the adoption of hearing aids include stigma, perceived ineffectiveness, ongoing costs (for batteries and maintenance), lack of comfort, and cosmetic appearance [7]. It is well documented that individuals who have hearing loss often complain of considerable complication understanding speech, especially in a background of noise. Recent advancements and improvements in digital hearing aid technology appear to have minimized this difficulty as evidenced by the subjective reports provided by many self-assessment hearing aid outcome measures [8]. Hickson et al. [9] observed that complication handling the hearing aids was associated with less use. These results relate to perceived benefit, perceived severity, perceived barriers and perceived self-efficacy. In the most recent World Hearing Report, WHO has published a revised estimate and now estimate that 430 million people have some form of hearing loss at a moderate level or worse [10]. Most people who experience hearing loss can be helped by prosthetic amplification devices in the form of hearing aids [11]. Unfortunately, many of those who could benefit from hearing aids do not use them. There are various reasons why not all with hearing loss use hearing aids but cost, poor access to hearing healthcare and lack of information are significant barriers to hearing aid uptake [12]. Hearing aid use is more widespread in affluent countries and regions [13].

Although it is established that more people could benefit from hearing aids, accurate estimates of hearing aid usage throughout the world are lacking. In a recent paper, the proportion of people in need who use hearing aids has been estimated for the regions of the world as defined by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) enterprise [12]. Despite this concern, researchers have yet to document in-depth, explicit reasons why young adult with Hearing Loss choose not to wear different types of hearing aid fitted for their use. Consequently, my thesis will focus on different complications associated with hearing aid fitting and the use of hearing aids among young adult and as well as compare this study with other research done in other countries. Understanding the reasons why adults do not to wear their hearing aids can enable hearing healthcare providers to provide, improved, person-centered care that could minimize young adult barriers to hearing aid use and subsequently foster hearing aid acceptance and consistent usage, and to suggest ways of solving the problems.

Rationale for the Study

In countries where there is access to quality audio logical assessment and services, like Nigeria, it is crucial to determine why many adult fitted with hearing aids having complication or issue (such as pre and post fittings issues, effect of socioeconomic factor on hearing aid fitted etc.) and then refused to use or dumped their hearing aid after fitting. There has been no previous study in Nigeria looking at rates, reasons and hearing aid fitting complications, though it has been carried out in some country, so this study will provide audiologists in Nigeria with identifying problem or complication confronting an many adult fitted with hearing aids refusing to use their device regularly, which will be necessary for devising appropriate rehabilitative strategies. This study fills a gap in the literature about complications associated with hearing aid fitted among adult (rates and reasons) in Nigeria population. There will likely be various self-reported reasons for hearing aid fitting complications among adult in Nigeria. In previous studies carried out in many countries, there have been numerous complications or reasons, as mentioned above, with each study finding slightly differing main reasons. Preventing or finding a solution to refusal of not using hearing aids fitted among adults might improve the efficiency of hearing care. Therefore, the perceived need for improved a hearing impairment intervention among adult seems to be the key factor in hearing aid fitting and use. Fitting hearing aids only to young or older adults who perceive a need for improved hearing, without proper selection of the right hearing aid that will suit his/her hearing problem and aftercare may discourage such adult not using hearing aid fitting, as well as limit or prevent the dispensing of hearing aids.

Aims of thesis

The aim of this study was to identify the main problems associated with hearing aid fitting and the use of hearing aid in adults across states in Nigeria via email and mobile phone interviews, to address the main problem to hearing aid use and target adults that real benefited from their hearing aids after fitting by the Audiologist, as well as compare it with other studies in other countries.

Methods

This study comprised two parts, descriptive and psychometric research design type of the survey. A cohort study was conducted in different states in Nigeria. Potential participants were identified from different teaching hospital or specialist hospital and hearing clinics in Nigeria. They were sent two different questionnaires or survey set including the hearing aid User’s Questionnaire (HAUQ) and HASKI-self via post or email via email, mobile phone or hard copy. A random sample of participants were selected and provided a second copy of the HASKI-self, enabling evaluation of test-retest reliability. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Office of The School of Advanced Education, Research and Accreditation, and institution certified by University Isabel I (Spain). All participants provided written consent to participate.

Materials

The HAUQ and HASKI questionnaire were chosen for this study. These are self-assessment questionnaires in which patients score the level of problems they are having in various situations. Participants completed a clinical history form, the HAUQ and HASKIself. The form was used to collect the participant’s response on difficulties facing after their hearing aid being fitted, demographic and bio data.

Participants

The target population for this study comprises of 250 young adult (male and female) with chronological age between 18- and 99-years cohort across all teaching hospital and hearing clinics in different regions (states) in Nigeria, who had hearing aid fitted and used as a result of unilateral or bilateral hearing loss in times past or who had been provided with hearing aids between 12 and 36 months prior to the date of data collection. Participants were contacted via mail, and mobile phone. The majority of participants were experienced hearing aid users, including independent participants with diverse perspectives, which contributed to the validity of the study, the clinical audiologists with postgraduatelevel qualification were also recruited with a good experience in dispensing and programming hearing aids across all centers, helping in collection of information.

Results

The data collected through the research instruments were analysed using frequency counts and percentages. In this section are tables and the results obtained from each questionnaire and interview question asked. The aim of the study was to explore in depth complications or problems and facilitators for hearing aid not being used after fitting among young adults. The analysis of the qualitative interview and questionnaire with 250 participants revealed different problems or difficulties.

Sample characteristics

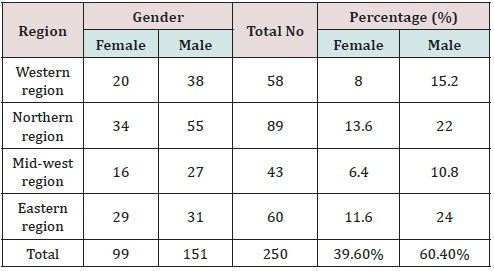

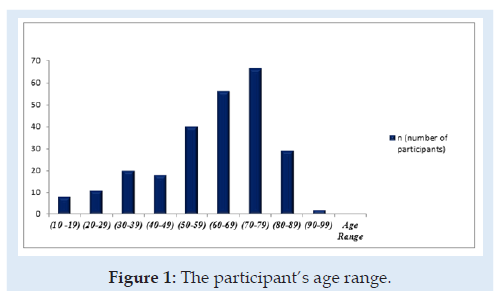

Two hundred and fifty participants were recruited in the study. The demographics of the participants are showed in the table below. Table 1 below shows the regional or state distribution of participants as well as their gender and age range in Figure 1 below. Participants were 99 (39.6%) female and 151 (60.4%) male recruited from different regions or states in Nigeria. The highest number of participants using hearing aids was gotten from the Northern region of the country. The participants’ ages ranged from 10-19 years (n=6); 20-29 years (n=11); 30-39 years (n=20), 40- 49 years (n=18), 50-59 years (n = 40); 60-69 years (n = 56); 70- 79 years (n = 68); 80-89 years (n = 29); 90-99 years old (n = 2). Participants wore behind-the-ear and in-the-ear style hearing aids from six different manufacturers.

Data Analysis and Discussion

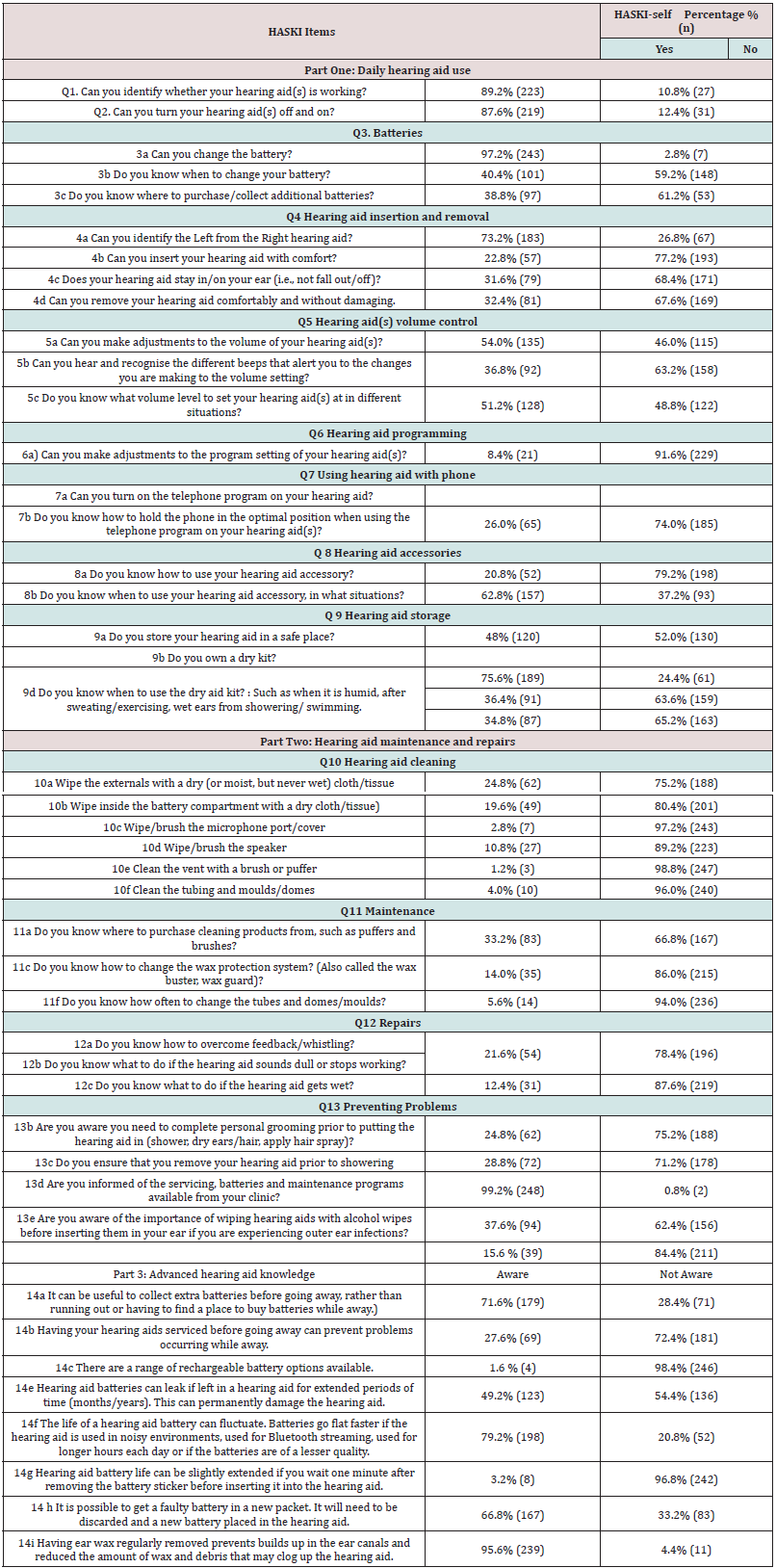

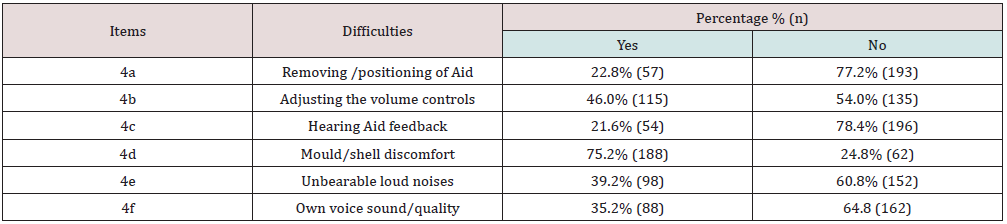

The aim of this study was to identify the main complication or difficulties facing with Hearing aid fitted among the adults, from the above Tables 2 & 3 above, number of hearing aid related problems was reported by participants, out of 250 adult hearing aid owners participating in this study, 80% indicated that they were experiencing at least one of the hearing aid problems or difficulties included on the survey. Individual participant’s problems ranged from 2.8% to 80%. Table 2 above was divided into three domains, and scores differed across the three domains or part based on different problems reported by the participants during the course of the survey: hearing aid management or daily hearing aid use section: Item 3. Do you have trouble changing the battery, or knowing when to change the battery? Do you know where to purchase/collect additional batteries, 2.8% reported having problem with item 3a, 59.2% (148) reported having difficulty with item 3b, while 61.2% (153) of the participants experienced challenge of where to get more battery. Item 4b to 4d from Table 2, about 67.6 % (169) to 77.2% (193) participants reported having difficulties with insertion and removal of their hearing aid. Item from Table 3, 4a, reported about 77.2% participants having issues with removing /positioning of their hearing aid.

Table 3: Participant Current Difficulties with the Hearing Aid fitted (Hearing Aid User’s Questionnaire, Question 4).

Table 2, item 6a, reported a 91.6% (229) out of 250 participants having problems on making adjustments to program setting of their hearing aid, while on (item 7), 74.0% (185) to 79.2% (198) reported having difficulties using their hearing aid with their phone. Table 2 (item 5) and Table 3 (item 4b) shows that hearing aid(s) volume control is another complication reported from the above data collected from the research, about 50.0% (125) experienced it. In Table 2 (item 9) 51.06% out of the participants reported having challenges with their hearing aid storage, as most of them don’t have personal drying kit or humidifier. From these findings, it shows that about 41.0% reported having battery difficulties, 71.0% insertion and removal of hearing aid difficulties, 52.6% hearing aid(s) volume control problems, and 76.6% of the participants reported difficulties using their phone with their hearing aid. While from Table 3 (item 4d), 24.8% (62) of participants are not comfortable with mould/shell. These findings support previous studies, which have found that, up to 90% of hearing aid owners demonstrate difficulties with basic hearing aid management tasks [14-16]. The hearing aid management skills identified to be most problematic on the HASKI-self [16]. The problems relating to hearing aid management identified in this study could become a checklist for the development of such materials to ensure they encapsulate the problematic aspects of hearing aid management as described by hearing aid owners and dispensing clinicians [16].

Hearing aid maintenance and sound quality: from Table 2, (item 10 to 11) about 82.2% to 89.4% of the participants reported having difficulties cleaning and maintaining their hearing aid due to the fact that the majority of them lack knowledge on different components or parts (i.e. battery compartment, microphone port/ cover, the speaker, the tubing and moulds/domes, and the vent of the aid), as many don’t know which part need cleaning if wax actually blocks the vent or the tube, where to purchase cleaning products from, such as puffers and brushes (66.8%), how to change the wax protection system (86.0%), tubes and domes/moulds (94.0%) which may affect the sound quality. Table 2 (item 12b) and Table 3 (item 4c) show that 78.4% (196) reported having difficulties with hearing aid feedback/whistling and do not know how to overcome the feedback, Table 3 (item 4f and 4e). A total of 64.8% (162) participants reported of voice sound hollow or echoing, while 60.8% (152) complain of their hearing aid making sudden unbearable loud noises. The findings of this study on the difficulty with hearing aid fitted among adults show that majority of the participants face challenges or difficulties with hearing aid maintenance. According to Goggins & Day, [4], the concept of hearing aid maintenance and repairs included tasks that may be considered more complex than the tasks included in the daily hearing aid use concept. The complexity may be due to the physical requirements of the task, for example, microphone covers can be small and fiddly to manage [17]. Additionally, tasks may be considered complex due to how infrequently they are performed, thus increasing the chance that hearing aid owners may forget how to perform the task or forget that the task is even necessary. To address this, clinicians should ensure that hearing aid owners have sufficient training and support at initial hearing aid fitting appointments and at intervals thereafter [17].

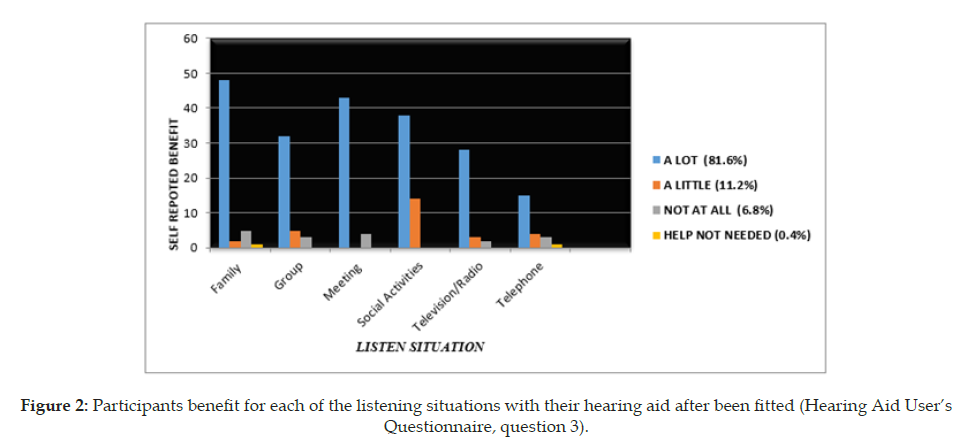

Figure 2: Participants benefit for each of the listening situations with their hearing aid after been fitted (Hearing Aid User’s Questionnaire, question 3).

For example, given that several maintenance tasks are required to be performed for the first time approximately three months after the initial hearing aid fitting appointment (such as wax protector/ microphone cover/ slim tube and dome replacement) it may be beneficial for clinicians to make contact with hearing aid owners at this time to remind them about these maintenance tasks and offer additional training and support. These sorts of additional services may be more necessary in older populations, as older adults have been found to be less knowledgeable about the complex features on their hearing devices than the basic features [18]. In another development, this study find out that adult fitted with hearing aids having difficulties with sound quality (feedback/whistling, echo, unbearable loud noise), hearing aid sound quality and performance described problems relating to hearing aid performance; this may be influenced by the clinicians’ programming of the hearing aid or the hearing aid owners’ expectation or use of the hearing aid, (Figure 2), 6.8% of the participants didn’t benefit, while 11.2% benefited a little bit for each of the listening situations with their hearing aid after been fitted due to the hearing aid sound quality problem which is about (n= 45) of the participants out of 250. According to study to the carried out by Bennett et al. [19], the problems relating to hearing aid sound quality and performance identified in this study reflect the multi-faceted nature of hearing aid use. For example: the limitations of current hearing aid technology, the hearing aid owners’ lack of understanding (or unrealistic expectations) as to what the hearing aid classifies as noise (for example, speech may be the preferred signal in some environments and deemed noise in others), the inappropriate programming of the hearing aid by the clinician or the inappropriate use of the hearing aid by the owner (such as using the wrong program for a particular environment).

Furthermore, the clinician must determine the appropriate direction and extent of the adjustment to be made based upon a clients’ subjective experience [20]. This is a complex process, and some clients may persist with underperforming or inappropriate hearing aid settings. Furthermore, these adjustments may need to be repeated several times before the client is happy with the settings or, in some cases, this may not eventuate, and the patient may persist with an underperforming hearing aid or cease wearing the hearing aid entirely. Through this process, clinicians generally address one problem at a time. For example, reducing high frequency amplification may overcome reports of disliking the harsh or sharp sound of their surroundings, but may simultaneously reduce audibility for female voices or impair functionality of directional microphones [19]. Participants in this study reported on whether they were aware of individual items of knowledge relating to hearing aid management. From this study, Table 2, (item 14), shows the five knowledge-based items that participants most often reported not being aware of included: 14b, having your hearing aids serviced before going away can prevent problems occurring while away (72.4%); 14c, there are a range of rechargeable battery options available (98.4%); 14e, hearing aid batteries can leak if left in a hearing aid for extended periods of time (months/years). This can permanently damage the hearing aid (54.4%); 14g, hearing aid battery life can be slightly extended if you wait one minute after removing the battery sticker before inserting it into the hearing aid (96.8%).

The four knowledge items that participants were most often aware of included: 14a, it can be useful to collect extra batteries before going away, rather than running out or having to find a place to buy batteries while away (71.6%); 14f, the life of a hearing aid battery can fluctuate. Batteries go flat faster if the hearing aid is used in noisy environments, used for Bluetooth streaming, used for longer hours each day or if the batteries are of a lesser quality (79.2%); 14h, it is possible to get a faulty battery in a new packet. It will need to be discarded and a new battery placed in the hearing aid (66.8%); 14i, having ear wax regularly removed prevents builds up in the ear canals, and reduced the amount of wax and debris that may clog up the hearing aid (95.6%). From these findings, lack of hearing aid knowledge or lack of information and training is one of the difficulties associated with the use of hearing aid fitted among the adults. It is possible that the majority of the participants fitted with hearing aids are not provided with the required information needed by their clinician about their hearing aid and this might pose a lot of difficulty to them in handling their hearing aid. Each item listed in this section of the survey was problematic to at least one participant, some might not recall, while some might forget some of the information provided by the clinicians [11]. It is also possible that clinicians are not providing the necessary information to every patient they see [19]. They assume the client will read the battery packet to learn about its use. Also, hearing aid owners often report wanting to be more informed about the devices they own and how to use them most effectively [19,21,22]. Hearing aid owners describe receiving little benefit from the written materials currently provided [19], most likely due to the low quality and poor readability of hearing aid user manuals [23] and the high level of health literacy required to understand the content of written information concerning hearing aids [24,25]. The HASKI-self offers clinicians a novel alternative to hearing aid education. Clinicians can administer the HASKI-self towards the end of the rehabilitation program, allowing hearing aid owners to self-evaluate their level of skill and knowledge, and simultaneously learn these items of skill and knowledge through the detailed descriptions provided in the survey [19].

This study also shows that over half (54%) of the difficulties reported by participants during the survey had not been reported to the clinic where their hearing aid was dispensed and fitted. This is a missed opportunity, as those problems that were identified as being least likely to be reported to the clinic were largely resolvable. For example, problems relating to wind noise (a vibrational sound caused by a turbulent flow of air hitting the microphone) can be reduced by decreasing the gain for low level inputs, increasing the compression ratio for high-level inputs, and activating modulationbased noise reduction algorithms [26]. Problems relating to device management (such as hearing aid retention and comfort, or use of the program buttons or dry aid kit) are solvable through device modification and client retraining [1,3,27]. Those participants who also reported difficulty managing the small components of the hearing aid (such as the microphone cover or dome or wax protection system), nearly half had reported these issues to the clinic, yet the problems persisted. Previous studies have indicated issues with the design of hearing aid features, including microphone covers that are too small for hearing aid owners to manage themselves [1] or manual controls that are difficult to manage due to age related reductions in dexterity and haptic touch. Targeted interventions may be the key to improving hearing healthcare clinicians’ listening and counseling skills in the audiology setting [28,29]. Informing clients of the common problems that arise with hearing aid ownership, teaching them how to prevent these problems from occurring, and empowering them with the skills and knowledge to address these difficulties. Hearing healthcare clinicians could reduce patient difficulties by increasing the use of helpful behaviors, such as offering written handouts or training materials [11], group training sessions [30] and by involving communication partners [31,32].

Limitations and future research

Getting information from some of the participants with hearing loss through telephone was very difficult, because they find it difficult to understand what I am discussing with them on the phone, where language barriers and as well as getting an interpreter is another key factor. To make things easy for them, an option of sending an email was put in place but some, cannot access their email, most especially the elderly due to internet problems. But face-to –face interview was arranged for effective data collection and information. My wish was to cover many states in Nigeria as well as increase the number of participants, but due to logistic problems and lack of fund, it was not possible. This study was conducted with a large sample and including many centers across different regions in Nigeria. All participants were adults fitted with hearing aids in the past few years. Further research investigating the experience of hearing aid problems in sub-populations such as those with poor dexterity or haptic touch, vision impairment, low working memory, or funding restrictions could provide valuable insight. In addition, looking at whether hearing aid owners’ self-reported hearing aid problems are congruent with clinicians’ perceptions of problem presence could be valuable as well.

Conclusion

Many hearing aid users experience difficulties with their hearing aids, many of which are never reported to the clinic or remain unresolved once reported. The problems related to the hearing aid management, hearing aid knowledge or lack of information and training, and sound quality and performance of the hearing aid was amongst the highest reported but unresolved experiences. Participants who reported experiencing a greater number of hearing aid problems also reported lower levels of hearing aid benefit and satisfaction with their hearing aids as well as lower knowledge and management skills. Addressing the devicerelated problems associated with hearing aid use would likely contribute to improved hearing aid fitting outcomes among the adults. According to Dullard & Cienkowski [18], additional services may be more necessary in older populations, as older adults have been found to be less knowledgeable about the complex features on their heari

References

- Global Burden of Disease (GBD) (2018) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A Systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Global health metrics 392(10159): 1789-1858.

- World Health Organization (2017a) Global tuberculosis report world health organization.

- World Health Organization (2006) Factsheet no 300: deafness and hearing impairments; providing key facts and information on causes, impact, prevention, identification and management.

- Goggins S, Day J (2009) Pilot study: Efficacy of recalling adult hearing-aid users for reassessment after three years within a publicly funded audiology service. International journal of audiology 48(4): 204-210.

- Kochkin S (2007) Marke Trak VII: Obstacles to adult non‐user adoption of hearing aids. The hearing journal 60(4): 24-51.

- Brooks DN (1989) The effect of attitude on benefit obtained from hearing aids. Br J audiology 23(1): 3-11.

- Strom KE (2006) The HR 2006 dispenser survey. Hearing review (13): 16-39.

- Mendel LL (2007) Objective and subjective hearing aid assessment outcomes. American journal of audiology (16): 118-129.

- Hickson L, Hamilton L, Orange SP (1986) Factors associated with hearing aid use. Australian journal of audiology (8): 37-41.

- World Health Organization (2021) World report on hearing. Geneva: world health organization 2020.

- Ferguson M, Brandreth M, Brassington W, Leighton P, Wharrad H (2016) A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the benefits of a multimedia educational program for first-time hearing aid users. Ear and hearing 37(2): 123.

- Orji A, Kamenov K, Dirac M, Davis A, Chadha S, et al. (2020) Global and regional needs, unmet needs and access to hearing aids. International journal of audiology 59(3): 166-172.

- Bright T, Wallace S, Kuper H (2018) A systematic review of access to rehabilitation for people with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. International journal of environmental research and public health (15): 21-65.

- Ferrari DV, Jokura PR, Silvestre NA, Campos PD, Paiva PMP (2015) Practical hearing aid skills test: results at the time of fitting and comparison of inter-rater reliability. Journal of audiology communication research 20(2): 110-115.

- Bennett RJ, Taljaard DS, Meyer C, Eikelboom RH (2017) Are hearing aid owners able to identify and self-report handling difficulties? International journal of audiology 56(11): 887-893.

- Bennett RJ, Meyer CJ, Eikelboom RH, Atlas MD (2018c) Evaluating Hearing Aid Management: Development of the Hearing Aid Skills and Knowledge Inventory (HASKI). American journal of audiology 27(3): 333-348.

- Bennett RJ, Jayakody D, Eikelboom RH, Taljaard DS, Atlas MD (2015) A prospective study evaluating cochlear implant management skills: development and validation of the cochlear implant management skills (CIMS) survey. Clinical otolaryngology 41(1): 51.

- Dullard BA, Cienkowski KM (2014) Exploring the relationship between hearing aid self-efficacy and hearing aid management. Perspectives on aural rehabilitation and its instrumentation 21(2): 56-62.

- Bennett RJ, Meyer CJ, Eikelboom RH (2018b) How do hearing aid owners acquire hearing aid management skills? Journal of the American academy of audiology (30): 516-522.

- Dillon H, Zakis JA, McDermott H, Keidser G, Dreschler W, et al. (2006) The trainable hearing aid: what will it do for clients and clinicians? The hearing journal 59(4): 30.

- Laplante Lévesque A, Hickson L, Worrall L (2010) Promoting the participation of adults with acquired hearing impairment in their rehabilitation. Journal of the academy of rehabilitative audiology (43): 11-26.

- Laplante Lévesque A, Jensen LD, Dawes P, Nielsen C (2013) Optimal hearing aid use: focus groups with hearing aid clients and audiologists. Ear and hearing 34(2): 193-202.

- Caposecco A, Hickson L, Meyer C (2014) Hearing aid user guides: suitability for older adults. International journal of audiology 53(1): 43-51.

- Brooke RE, Isherwood S, Herbert NC, Raynor DK, Knapp P (2012) Hearing aid instruction booklets: employing usability testing to determine effectiveness. American journal of audiology 21(2): 206-214.

- Nair EL, Cienkowski KM (2010) The impact of health literacy on patient understanding of counseling and education materials. International journal of audiology 49(2): 71-75.

- Chung K (2012) Wind noise in hearing aids: I. Effect of wide dynamic range compression and modulation-based noise reduction. International journal of audiology 51(1): 16-28.

- Saunders GH, Morse-Fortier C, McDermott DJ, Vachhani JJ, Grush LD, et al. (2018) Description, normative data, and utility of the hearing aid skills and knowledge test. Journal of the American academy of audiology 29(3): 233-242.

- Coleman CK, Muñoz K, Ong CW, Butcher GM, Nelson L, et al. (2018) Opportunities for audiologists to use patient centered communication during hearing device monitoring encounters. Seminars in hearing 39(1): 32-43.

- Munoz K, Ong CW, Borrie SA, Nelson LH, Twohig MP (2017) Audiologists' communication behaviour during hearing device management appointments. International journal of audiology p. 1-9.

- Collins MP, Liu C, Taylor L, Souza PE, Yueh B (2013) Hearing aid effectiveness after aural rehabilitation: individual versus group trial results. Journal of rehabilitation research & development 50(4): 585-598.

- Preminger JE (2003) Should significant others be encouraged to join adult group audiologic rehabilitation classes? Journal of the American academy of audiology 14(10): 545-555.

- Preminger JE, Lind C (2012) Assisting communication partners in the setting of treatment goals: The development of the goal sharing for partners strategy. Seminars in Hearing 33(1): 53-64.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...