Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Case Report(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Combined Surgical Approach Via Orbitozygomatic Craniotomy and Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Giant Frontoethmoidal Osteoma Spreading into Orbit and Anterior Cranial Fossa Volume 6 - Issue 5

Karina Rapsa*, Ingus Vilks and Jegors Safronovs

- Department of Otorhinolaringology, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia, Europe

Received:June 01, 2021 Published:June 11, 2021

Corresponding author: Karina Rapsa, Department of Otorhinolaringology, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia, Europe

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2021.06.000246

Abstract

Introduction: Osteoma is the most common benign paranasal sinus tumour. In majority of cases, it is asymptomatic and is diagnosed by chance. We report on a case of giant frontoethmoidal osteoma with intraorbital and intracranial spread. Combined surgical approach was chosen for management of this case. Immediate reconstruction of medial orbital wall and anterior skull base was performed.

Case Description: 25 years old man presented to otorhinolaryngology department due to incidental computed tomography finding. Giant osteoma of the right frontoetmoidal region spreading into an orbit and anterior cranial fossa was identified on computed tomography. The patient was absolute candidate for surgical treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed to view possible involvement of adjacent intraorbital and intracranial anatomical structures. Right side orbitozygomatic craniotomy and endonasal endoscopic surgery were performed for removal of osteoma. On control computed tomography 12 months after surgery there were no pathological changes or reccurrence of osteoma.

Conclusion: Surgical approach for osteoma management should be chosen according to its size, localization and involvement of adjacent anatomical structures. For giant osteomas, spreading outside paranasal sinuses, endoscopic approach perspectives are limited. Multidisciplinary approach is of a vital importance to achieve the best treatment outcome.

Keywords:Frontoethmoidal osteoma; giant osteoma; bicoronal incision; orbitozygomatic craniotomy; FESS

Introduction

Osteoma is the most common benign sinonasal tract tumour. It grows slowly and in majority of cases is asymptomatic. Symptoms depend on size, localization of the tumour and its relation to adjacent anatomical structures. The most frequent localization of osteoma is frontoethmoidal region, with a major prevalence in frontal sinus, followed by maxillary and sphenoid sinuses [1]. Osteomas exceeding 30 mm in diameter are considered to be giant. Primary intracranial or orbital involvement is extremely rare. In most cases osteoma is diagnosed accidentally on computed tomography scans of asymptomatic patients. Surgical treatment is indicated for patients with symptomatic osteoma, fast-growing osteoma and in cases with intraorbital or intracranial spread and subsequent complications [2,3]. Variable surgical approaches are possible for management of osteoma. An approach is chosen according to the size and localization of osteoma, professional experience of the surgeon and available equipment [3,4]. We report on a case of giant frontoethmoidal osteoma on the right side with intraorbital and intracranial spread. Combined open and endoscopic approach was chosen for management of this case. Immediate reconstruction of superomedial portion of orbital wall and anterior skull base was performed.

Case Description

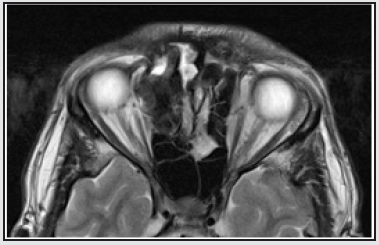

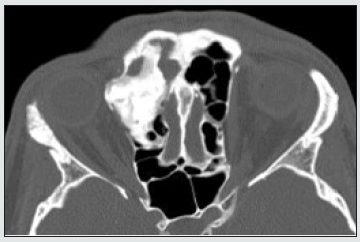

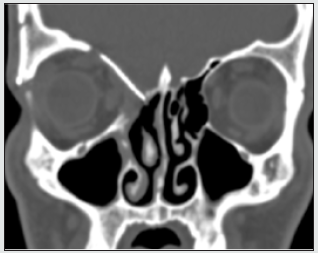

A 25-year-old man presented to outpatient otorhinolaryngology department of Riga Stradins Clinical University hospital in July 2019 due to incidental computed tomography (CT) finding. He had a single syncope episode in May 2019, when CT investigation was performed. On CT scan a giant osteoma of the right frontal and ethmoidal sinuses spreading into an orbit and anterior cranial fossa sized about 37.3 x 22.23 x 24.94 mm was identified (Figures 1 & 2). During the consultation the patient complained about headache localized mainly in forehead region, nasal congestion and difficulty in nasal breathing with progressing obstruction of right nasal passage for the last two years. He also mentioned a feeling of pressure in right eye and epiphora of the right eye for approximately five years. Relatives of the patient had noticed slowly appearing deforming changes in his face, including telecanthus and proptosis of his right eye. The patient had no vision impairment and extra-ocular movements were not restricted. On focused interviewing about anamnesis data the patient denied having any head trauma, recurrent, chronic sinusitis or any other chronic diseases. No cases of osteoma or intestinal polyposis in family anamnesis. The patient was absolute candidate for surgical treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to view possible involvement of adjacent intraorbital and intracranial anatomical structures. On MRI slight lateralization of medial orbital rectus muscle and optic nerve was identified (Figure 3). To work out a precise surgical plan multidisciplinary consultation meeting with ENT surgeon, neurosurgeon and maxillofacial surgeon was organized. It was decided to manage the tumour in combined surgical approach, combining osteoplastic flap procedure with right side orbitozygomatic craniotomy and endonasal endoscopic surgery in continuation.

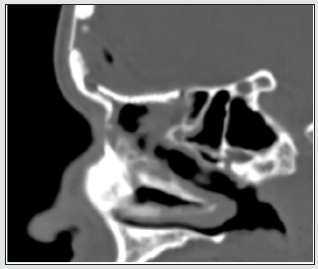

Figure 2: Preoperative axial CT scan. Osteoma spreading into the orbit, tensioning m rectus medialis.

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia and neuronavigation control. The surgery was started with a bicoronal incision. Skin and aponourotic tissue were detached in a subgaleal plane, preserving supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves. Skin and periosteum above the glabella were elevated as well. Pericranial flap for closure of anterior skull base defect was prepared. We also identified and preserved the frontal branch of facial nerve. A right orbitozygomatic craniotomy was performed. Osteoma fragment from right frontal sinus was drilled out, revealing a huge defect in its posterior and inferior walls. Afterwards relevant osteoma from ethmoidal cells and medial part of right orbit was drilled out and evacuated, leaving a significant defect in medial wall of the right orbit. Immediate reconstruction of medial orbital wall by individually designed titanium mesh was made. The defect in anterior skull base was lined by pericranial flap. Autologous abdominal fat graft was used for obliteration of the right frontal sinus. The osseous craniotomy fragment was fixed in place by titanium clamp and mesh. Previously detached skin and aponeurotic layers were lifted backwards and a bitemporal coronal incision was closed with separate sutures and drainage was inserted. The surgery was continued via endoscopic endonasal approach. A maxillotomy II and anterior ethmoidotomy on right side were performed. Defect in medial orbital wall partly covered by titanium mesh was visualized. Residual osteoma fragment was removed from anterior ethmoids and orbit. No residual osteoma on control CT was identified. Postoperative recovery period was without any complications. Proptosis almost resolved postopertively and telecanthus remained residual. The patient did not complain about any other ophthalmologic symptoms. A histopathologic examination confirmed diagnosis of osteoma. The patient was discharged from the hospital 12 days after surgery. The patient was watchfully observed in outpatient setting. On first control visit one month after surgery he had no complaints. On endoscopic examination there was some crusting in nasal cavity and epithelisation in progress. The external surgical wound was well camouflaged in hairline, proptosis resolved as well, confirming good aesthetic result. On control CT 12 months after surgery there were no pathological changes or reccurrence of osteoma. Skull base defect and medial orbital wall defect were covered with titanium mesh (Figures 4 & 5). No residual defects were observed. The patient had no complaints and was satisfied with an aesthetic result.

Figure 4: Postoperative coronal CT scan, 1 year after the surgery. Superior orbital wall reconstructed by titanium mesh. No scull base defect observed.

Figure 5: Postoperative sagittal CT scan, 1 year after the surgery. Scull base defect covered by titanium mesh.

Discussion

Osteoma is the most common benign sinonasal tract tumor, usually presenting between the second and sixth decades of life, with a slight male predominance. It grows slowly and in majority of cases is asymptomatic. In study of P Koivunen et al., on a growth rate of sinonasal tract osteomas, the mean growth rate was 1.61 mm a year, with a range from 0.4 to 6.0 mm a year [5]. It explains asymptomatic course of tumor for several years till exposure of first symptoms. In most cases osteoma is diagnosed accidentally on computed tomography scans performed because of other reasons [6]. The most frequent localization of osteoma is frontoethmoidal region, with a major prevalence in frontal sinus, followed by ethmoid, maxillary and sphenoid sinuses. Usually, size of osteoma varies from 2 to 30 mm. Osteomas exceeding 30 mm in diameter are considered to be giant. Giant osteomas are very rare and usually symptomatic, with a high potential for possible complications. Symptoms depend on size, localization of the tumour and its relation to adjacent anatomical structures. Osteomas of frontoethmoidal region can cause sinus drainage problems resulting in sinusitis or mucocele. Patients may complain on headache, nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, hyposmia or anosmia [6]. Primary intracranial or orbital involvement is extremely rare and, in most cases, appears as a complication. Osteomas of frontal and ethmoidal sinuses may spread into orbit, causing proptosis, diplopia and epiphora in case of lacrimal system involvement. Compression and tension of optic nerve results in decreased visual acuity or even transient blindness. In case of intracranial spread, risk of cerebrospinal fluid leak, pneumocele, meningitis, and brain abscess is present. In reported case both intraorbital and intracranial spread were present. No intracranial complications were present. In accordance with intraorbital involvement, the patient had proptosis, epiphora, but no diplopia and decrease of visual acuity.

According to available literature, there are three main developmental theories of osteoma. Embryologic theory explains development of frontoethmoidal osteoma, in an origin of embryonic frontal membranous and ethmoidal cartilaginous bone. Another, traumatic theory, associate’s development of osteoma with previous trauma, including surgical trauma as well. The third theory is chronic infection and inflammation process in paranasal sinuses. Two latter leading to osteoblastic proliferation and activation of osteogenesis. Osteomas may also be observed as a part of Gardner syndrome, which is genetic autosomal dominant disorder manifesting with intestinal polyposis, multiple osteomas and multiple soft tissue tumors [7]. The patient was interviewed about all possible causative factors and family anamnesis. There were no data confirming traumatic or chronic inflammation theory and Gardners syndrome as well. We can assume developmental etiology in this case. The cornerstone of diagnostic imaging of osteoma is computed tomography. It allows evaluating size and origin of osteoma, its location in different planes and possible invasiveness. According to CT finding the surgical plan should be developed. In cases of intracranial of intraorbital spread MRI is recommended to see relation of osteoma to soft tissues. Asymptomatic and incidentally diagnosed osteomas mainly do not require surgical intervention and can be managed conservatively [9]. Close observation is advised. Although, in some asymptomatic cases surgical treatment is indicated. Fast growing osteomas, tumours of sphenoid sinus or frontal recess and tumours occupying more than 50 % of the frontal sinus demand surgical treatment [6,9,10].

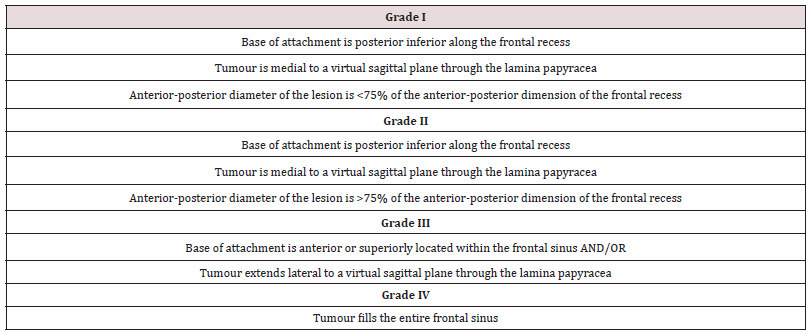

Being initially asymptomatic, these tumors may cause threatening complications. In time resection of osteoma allows avoiding complication and demands lesser amount of reconstruction. In cases of symptomatic osteoma or intraorbital or intracranial spread of tumor, surgery is a treatment of choice. Variable surgical approaches are possible for management of osteoma. An approach is chosen according to size and localization of osteoma, and skills of the surgeon. In preendoscopic era management of frontoetmoidal region osteomas via external approach was a gold standard. Osteoplastic flap procedure (OFP), Lynch frontoethmoidectomy and lateral rhinotomy were traditional approaches for tumors of frontoethmoidal region. Nowadays, proceeding to experience and practical skills of the surgeons, and availability of multiangled endoscopes and angled drills, endoscopic techniques became a valid alternative in particular cases. Advantages of endoscopic approach are lower postoperative morbidity, shorter hospital stay and better aesthetic result. Chi et al. in their study on surgical decision in management of frontal sinus osteomas described grading system for frontal sinus osteomas. They divided osteomas in to four grades according to three variables: location of the origin of attachment, location of the lesion in relation to virtual sagittal plane through the lamina papyracea and the anterior-posterior diameter of osteoma in relation to the anterior-posterior diameter of the frontal recess (Table 1) [11]. According to this classification endoscopic approach is suggested for grade I and grade II lesions. For lesions meeting criteria of Grade III and IV combined or external approach was suggested [11]. Study of Seiberling et al. described entire endoscopic approach with Draf III median drainage (Lothrop modified procedure) for Grade III and IV tumors, proving validity of endoscopic surgery as alternative to external approach for laterally located tumors, large tumors and tumors spreading outside sinonasal tract. Precise indications for purely endoscopic approach are still controversial. Careful analysis of CT scan, determining surgical anatomy (anteroposterior diameter of frontal sinus floor in relation to frontal sinus volume has to be taken into account when planning surgery, because it predicts possible maneuverability of instruments in frontal sinus cavity), dimensions and localization of the tumour (localization and site of attachment of osteoma is more important factor than its size in decision on surgical approach), involvement of neighboring anatomical structures, is essential for preoperative determination of surgical approach.

In every case surgeon has to be ready shifting to an external approach if required [9,10]. M Turri-Zanoni et al. in article on frontoetmoidal and intraorbital osteomas described their suggested exclusion criteria for an exclusively endonasal endoscopic approach, which are: a small anteroposterior diameter of frontal sinus in relation to large volume of frontal sinus; erosion of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus, extension of the tumour through the anterior frontal plate; relevant posttraumatic anatomical changes in the frontal bone structure and lateral or superolateral orbital wall attachment of the lesion. In such cases, external or combined approach is suggested [8]. In described case precise site of origin of lesion was not identifiable, the tumor was extending into orbita and a defect in posterior wall of the frontal sinus was present. To provide wide surgical field for better visualization and preservation of important anatomical structures orbitozygomatic craniotomy and subsequent endonasal endoscopy were performed. External approach allows bimanual instrumentation and provides good access to osteomas propagating outside the frontal sinus and sinonasal tract [9]. Maintenance of functional frontal sinus outflow could not be preserved. Mucosal lining of frontal sinus and frontal recess was damaged which implied a high risk of stenosis and disfunction of sinus drainage system. To prevent possible future complications, obliteration of frontal sinus with autologous periumbilical fat material was performed. Chosen approach provided good long-term functional and satisfactory aesthetic result.

Conclusion

Variable surgical approaches are possible for management of osteoma. An approach should be chosen according to its size, localization, site of attachment, involvement of adjacent anatomical structures, individual anatomical features of the patient and experience and mastering degree of the surgeon. Technical equipment accessibility plays an important role in choice of surgical approach as well. Preoperative CT scan review has a great importance in development of surgical plan. Nowadays, purely endoscopic approach has expending perspectives in management of giant osteomas, spreading outside paranasal sinuses. Although, there are particular cases best managed via open approach. Multidisciplinary approach and cooperation are of a vital importance to achieve the best treatment outcome for the patient.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Raimonds Mikijanskis, neurosurgeon, at Pauls Stradins Clinical University hospital, and Anna Ivanova, maxillofacial surgeon, at Pauls Stradins Clinical University hospital, for their contribution in development of treatment plan and surgery of the patient.

Authorship Contribution

KR: literature studying and selection, manuscript production. IV: manuscript review. YS: manuscript review.

Conflict of Interest

No applicable.

Funding

No applicable.

References

- Monil Parsana, Rajesh Vishwakarma, Abhishek Gugliani, Kalpesh Patel (2019) Combined Approach Excision of a Giant Frontal Sinus Osteoma: Case Report with Literature Review. Scholarly Journal of Otolaringology 3(2).

- Maria Humeniuk Arasiewicz, Grażyna Stryjewska Makuch, Małgorzata A Janik, Bogdan Kolebacz (2018) Giant fronto-ethmoidal osteoma - selection of an optimal surgical procedure. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 84(2): 232-239.

- R Sanchez Burgos, J González Martín-Moro, J Arias Gallo, F Carceller Benito, M Burgueño García (2013) Giant osteoma of the ethmoid sinus with orbital extension: craniofacial approach and orbital reconstruction. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica 33(6): 431–434.

- Codrut Sarafoleanu, Roxana-Elena Decusara (2016) Frontal sinus osteoma. Romanian Journal of Rhinology 6(22).

- Koivunen P, Löppönen H, Fors AP, Jokinen K (1997) The growth rate of osteomas of the paranasal sinuses. Clinical Otolaryngology& Allied Sciences 2: 111-114.

- Piero Nicolai, Davide Mattavelli, Paolo Castelnuovo (2011) Benign Tumors of the Sinonasal Tract. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery 50: 773-787.

- Sapna Panjwani, Anjana Bagewadi, Vaishali Keluskar, Saurabh Arora (2011) Gardner’s Syndrome. Journal of Clinica Imaging Science 1: 65.

- Mario Turri-Zanoni (2012) Frontoethmoidal and Intraorbitas Osteomas. Exploring the Limits of the Endoscopic Approach. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 138(5): 498-504.

- Ashok Rokade, Anshul Sama (2012) Update on Management of Frontal Sinus Osteomas. Curr Opin Otolaringol Head and Neck Surg 20: 40–44.

- Kristian Seiberling (2009) Endoscopic management of frontal sinus osteomas revised. Am J Rhinol Allergy 23: 331-336.

- Alexander G Chiu (2005) Surgical Decisions in the Management of frontal Sinus Osteomas. Americal Journal of Rhinology 19(2): 191-197.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...