Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Burnout Syndrome Among Otorhinolaryngologists during COVID-19 Pandemic Volume 8 - Issue 3

Nora Siupsinskiene1, Brigita Spiridonoviene2, Agne Pasvenskaite2, Justinas Vaitkus2 and Saulius Vaitkus2

- 1Department of Otolaryngology, Academy of Medicine, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania, Faculty of Health Sciences, Klaipeda University, Klaipeda, Lithuania

- 2Department of Otolaryngology, Academy of Medicine, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Lithuania

Received: May 25, 2022; Published: June 13, 2022

Corresponding author: Agne Pasvenskaite, MD, PhD, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2022.08.000288

Abstract

Objectives: To determine the prevalence of burnout syndrome among otorhinolaryngologists in Lithuania and investigate associations with sociodemographic and professional factors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: Burnout was measured using the validated Lithuanian Version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Demographic characteristics and professional characteristics were collected utilizing an anonymous questionnaire.

Results: 80 otorhinolaryngologists (ORL group) and 30 information technology specialists (the control group) were enrolled in this study. A high level of professional burnout in at least one of the subscales was observed in 82.5% of the ORL group subjects. Depersonalization and burnout syndrome were more frequently detected with increasing age in the ORL group (r=0.2, p<0.04). Greater satisfaction with salary and working environment resulted in a lower burnout incidence (r=0.31, p=0.001).

Conclusion: During the Covid-19 pandemic, the incidence of burnout syndrome is high among Lithuanian otorhinolaryngologists. Demographic and professional characteristics are significantly related to burnout syndrome for Lithuanian otorhinolaryngologists.

Keywords: Burnout syndrome; otorhinolaryngologist; depersonalization; Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19), discovered in 2019 in China, remains a major health system crisis [1]. Otorhinolaryngologists are one of the specialists that have direct contact with patients infected by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and also have a great risk of becoming infected as they perform mucosal or aerosol-generated procedures daily (flexible/rigid endoscopy, sample taking, tracheostomy procedures, surgeries) [2]. Moreover, changed working conditions involving special equipment usage (FFP3/ N95 mask, disposable and fluid resistant gloves, gown, glasses, or full-face shield) and an increased workload is challenging. Hence, working in a risky environment not only physical health but also mental well-being (increased symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety) should be considered. Burnout is a syndrome involving emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment, which is primarily determined by stress at work [3]. In 1981 Christina Maslach introduced the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), a tool for measuring burnout syndrome which is most widely used for burnout syndrome assessment to date [4]. Maslach defined burnout syndrome as emotional exhaustion that is a result of stress caused by interpersonal interaction [5]. The model proposed by Maslach encompasses three dimensions (subscales) of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment at work [6]. This condition is included in the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10): the term ‘burnout’ is described as a “Burnoutstate of total exhaustion” [7].

It is essential to investigate professional burnout among health care workers during outbreaks to prevent any immediate or longlasting implications. For this reason, specialists that have a direct touch with the COVID-19 pandemic – otorhinolaryngologists – were selected for the present study. According to the literature, in the USA the prevalence of burnout among otorhinolaryngologists during the COVID-19 pandemic is 21.8% [8]. However, the prevalence of moderate to high burnout among academic otorhinolaryngologists in the USA can range from 70% to 75% [9]. In addition, some studies investigated associations of burnout and the presence of physical diseases and found strong links between exhaustion and depersonalization with musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and other physical diseases [10]. Moreover, burnout in health care workers is associated with poorer self-rated health, increased depression, increased anxiety, sleep disturbances, and impaired memory [11]. To date, there are no data concerning the mental health of Lithuanian otolaryngologists. Only a few studies regarding the mental health of other medical specialists have been reported indicating highly increased burnout rates as well as an experience of severe stress and low job satisfaction [12]. In the context of other European countries not enough research on professional burnout syndrome among otorhinolaryngologists has been presented either. This study aimed to determine the prevalence and associated risk factors for burnout syndrome among otorhinolaryngologists in Lithuania during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was approved by Kaunas Regional Bioethics Committee, for Biomedical Research Lithuanian University of Health Sciences (LUHS) (Approval No. BE 2-2). All study concerning procedures were accomplished following the Declaration of Helsinki. An Informed Consent Form was obtained from all participants.

Design

This cross-sectional, survey-based, national study was conducted from July to December of 2020. The study involved otorhinolaryngologists and IT specialists from five biggest cities of Lithuania working at national hospitals (Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kauno Klinikos, Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos, Republican Hospital of Vilnius, University Hospital of Klaipeda, Republic Hospital of Klaipeda, Republican Siauliai Hospital, Panevezys Republican Hospital) who attended scientific conferences organized by Lithuanian Otorhinolaryngologists Society of Lithuania.

Sample calculation size

According to Lithuanian Otorhinolaryngologists Society data (lit. Lietuvos otorinolaringologų draugija), there are 266 otorhinolaryngologists in Lithuania (http://otorinolaringologai. org/home/istorija/otorinolaringologija-lietuvoje/). For this study we selected randomly every third Lithuanian otorhinolaryngologist. Every third randomly selected IT specialist from 87 working in selected hospitals was involved in this study. The sample size calculation was based on the frequency with a 5% probability of error and 95% reliability and was calculated according to Sample size calculation in cross-sectional studies [13]. It was calculated that the collected sample size is sufficient to reach 80% or higher statistical power. Furthermore, within a cross-sectional study, a sample size of at least 60 participants is recommended [14]. Hence, a larger sample size gives greater power and is more ideal for a strong study design.

Study population

110 subjects were involved in the study: 80 otorhinolaryngologists (92.5% otorhinolaryngologists and 7.5% otorhinolaryngology residents) composing the ORL group and 30 informative technology (IT) specialists from a private company referring to the control group. IT specialists were chosen as a control group because their work is not recognized as emotionally debilitating. Both study groups were required to present their sociodemographic data. Salary and satisfaction with the work environment were measured on the visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 5 (0 – completely dissatisfied, 1 – dissatisfied, 2 – moderately satisfied, 3 – satisfied, 4 – sufficiently satisfied, 5 – fully satisfied). Additional questions were applied for the ORL group: type of hospital, working occupation, pedagogical status, patients per week, surgeries per week and to state whether they were working in the private or public sector.

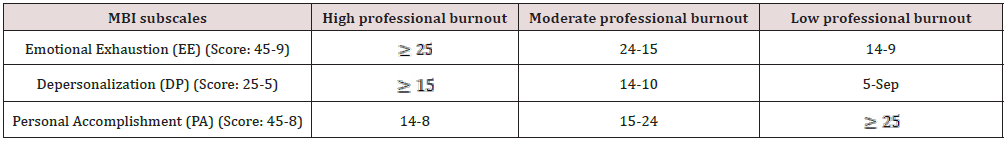

Burnout Measure

The phrase “professional burnout” was estimated using the Lithuanian Version of the MBI. This tool was chosen as it is considered to be the most commonly used implement of similar studies [15]. The MBI instrument has been already translated to Lithuanian, validated, and utilized in professional burnout studies in Lithuania [12,16,17]. The Lithuanian version of MBI is available to purchase together with the original MBI license [12]. The Lithuanian 22-item MBI version is also divided into three subscales: the 9 -item Emotional Exhaustion (EE) scale, the 5-item Depersonalization scale (DP), and the 8-item lack of Personal Accomplishment (PA). Fort his study instead of a classic 7-point Likert type scale, a 5-point Likert type scale was chosen as it has been most recommended by the researchers that it would reduce the frustration level of the respondents and increase response rate and response quality [18]. Moreover, it is suggested that a 5-point scale is more appropriate for European surveys [19]. In addition, a 5-point Likert scale was utilized as an effective approach to investigate the assessment of burnout syndrome influencing factors among doctors providing medical care in Lithuania [20]. The study groups were asked to answer each item on self-completed a Likert type scale type with 5 points (1 – strongly disagree, 2 – disagree, 3 – neither agree nor disagree, 4 – agree, 5 – strongly agree). According to the literature, there is no comprehensible agreement on how to interpret burnout based on the MBI normative scores. Grunfeld et al. and Wisetborisut et al. determined burnout as high scores in any subscale (EE, DP, or PA) [21,22]. Moreover, Ramirez et al. and Tironi et al., defined burnout when the scores in all three subscales are high [23,24]. Furthermore, according to recent studies, burnout is defined as a high score in either the EE or DP subscales and a low score in the area of PA [25]. For the present study higher scores in the EE and DP subscales and lower scores in the PA subscale indicated a higher burnout symptom burden. The adjusted normative scores of the MBI subscales are presented in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS/W 22.0 software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Student’s t-test was obtained for testing hypotheses about the equality of means. For testing hypotheses about independence, the chi-square test was performed. To assess the correlation between variables Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients (r) were applied. The differences among means were evaluated by Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The findings were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

Results and Analysis

Demographics

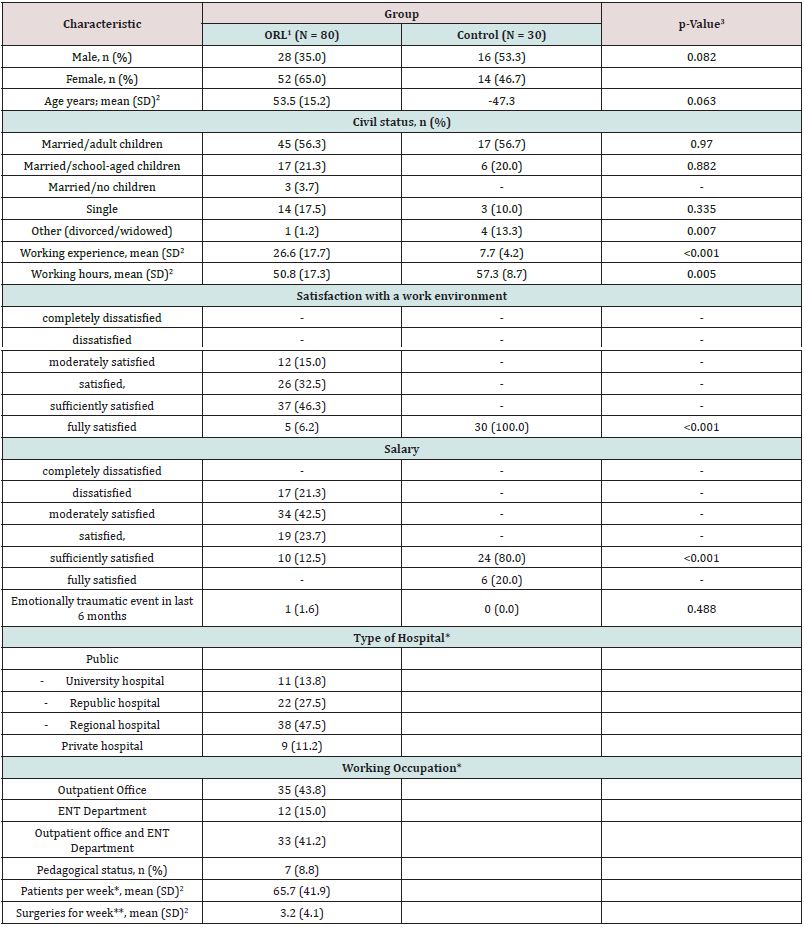

Table 2 presents sociodemographic data of the ORL and the control groups. Study groups were homogeneous according to age and gender (respectively, p=0.063; p=0.082). The working year experience in the ORL group was statistically significantly higher compared to the control group (p<0.001). However, the control group subjects were statistically significantly working more hours per week compared to the ORL group (p=0.005). Despite that, all control group subjects were fully satisfied with the working environment meanwhile 93.5% of the ORL group subjects were not satisfied with the working environment (p<0.001). Moreover, the satisfaction of the salary was statistically significantly higher in the control group – sufficiently satisfied were 80.0% of the control group subjects, whereas in the ORL group just 12.5% of subjects were sufficiently satisfied with the salary (p<0.001). Both groups almost did not refer to emotionally traumatic events in the last 6 months (divorce, loss of a relative, job loss, etc.) (p=0.553) (Table 2). Considering that the working occupation can impact the results of the ORL group (not all otorhinolaryngologists perform surgeries and make night shifts) we have selected otorhinolaryngologists who have a different daily occupation: otorhinolaryngologists working only at the Outpatient Office (43.8%), otorhinolaryngologists working only in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology (15.0%) and those who work in both subscales - Outpatient Office and the Department of Otorhinolaryngology (41.2%). We would like to emphasize that Otorhinolaryngologists working only in the Outpatient office did not provide surgical treatment, but they were receiving more patients - 70.4 per/week, while otorhinolaryngologists working in both subscales had 59.7 (33.1) patients per week. However, these results statistically significantly did not differ (p=0.148). The mean of performed surgeries by otorhinolaryngologists who worked in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology was 3.2 (4.1) per week. In addition, to obtain more certain results in the present study we involved otorhinolaryngologists who work in the different types of hospitals – public (University, Republican, and regional hospitals) or private hospitals. 8.8% of otorhinolaryngologists from the University hospitals also were working in the pedagogical area (Table 2).

1ORL: otorhinolaryngologists group; 2SD: standard deviation; 3p-Value: significance level p< 0.05. *Only ORL group; **Only 39 otorhinolaryngologists involved (working in ENT Department and Outpatient office and ENT Department).

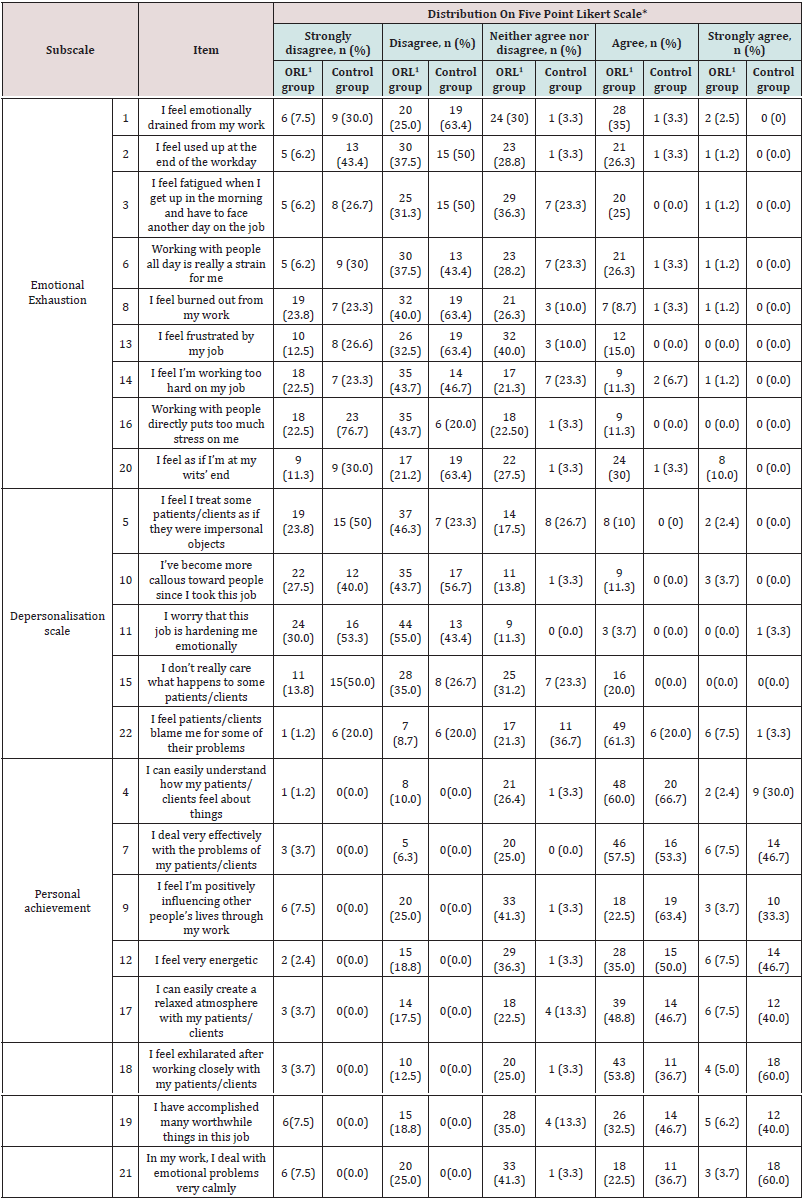

MBI score

Table 3 presents the distribution of the results according to the 22-item MBI. In the Emotional Exhaustion (EE) subscale, 35.0% of the ORL group referred that they agree feeling emotionally drained from work, meanwhile just 3.3% of the control group agreed with the statement (p<0.001). More than a quarter of the ORL group (26.3%) agree that they feel used up at the end of the workday, whereas in the control group there were just 3.3% of subjects who felt used up at the end of the workday (p<0.001). Moreover, a quarter of the ORL group subjects (25.0%) agree that they get up already fatigued while no subjects of the control group agreed with this statement (p<0.001). Only 3.3% of the control group agreed that working with people all day is really a strain. However, in the ORL group, 26.3% of the subjects agreed that working with people all day is really a strain for them (p<0.001). The distribution of the question about feeling burned out from work was similar in both groups, demonstrating a slightly higher incidence in the ORL group (p=0.07). 63.4% of subjects of the control group and 32.5% of subjects of the ORL group disagreed that they feel frustrated by their job (p=0.003). The results of answering the question about working too hard were very similar in both groups (p=0.779). 11.3% of the ORL group subjects agreed with the statement that working directly with the people puts too much stress on them, meanwhile no subjects of the Control group agreed with this statement (p=0.05). Almost one-third (30.0%) of the ORL group subjects agreed that they feel as if they are at their wits’ end, whereas just 1 subject (3.3%) of the control group agreed with this statement (p=0.003).

1ORL: otorhinolaryngologists group; n: number of subjects, *: the ORL group was composed of 80 subjects and the Control group of 30 subjects.

In the Depersonalisation Scale (DP) subscale, 23.8% of the ORL group subjects and 50.0% of the Control group subjects strongly disagreed that they feel like they treat some patients/clients as if they were impersonal subjects (p<0.001). In the ORL group, 11.3% of the subjects agreed and 3.7% of the subjects strongly agreed that they have become more callous toward people since they took this job, whereas no subjects of the Control group agreed or strongly agreed with this statement ((p<0.001). In both groups, subjects disagreed that they worry that their job is hardening them emotionally (55.0% of the ORL group vs. 43.4% of the Control group) p=0.280. One-fifth of the ORL group (20.0%) agreed that they don’t really care what happens to some patients. In addition, in the Control group, no one of the subjects agreed that they don’t really care what happens to their clients (p<0.001). In the ORL group, 61.3% of the subjects agreed that they feel patients blame them for some of their problems, furthermore, one-fifth (20.0%) of the Control group subjects also agreed that they feel clients blame them for some of their problems (p<0.001). In the Personal Achievement subscale, only 2.4% of the ORL group subjects strongly agreed that they could easily understand how their patients feel about things, while 30.0% of the Control group subjects strongly agreed that they could easily understand how their clients feel about things (p<0.001). Almost half (46.7%) of the Control group subjects strongly agreed that they deal very effectively with the problems of their clients, whereas just 7.5% of the ORL group subjects strongly agreed with the statement (p<0.001). One-third (33.3%) of the Control group strongly agreed that they feel positively influencing other people’s lives through their work, however, just 3.7% of the ORL subjects strongly agreed with the question (p<0.001). Almost half (46.7%) of the Control group subjects strongly agree that they feel very energetic, whereas only 7.5% of the ORL group subjects strongly agree to feel very energetic (p<0.001). Both groups agreed similarly that they can easily create a relaxed atmosphere with patients or clients (48.8.% of the ORL group vs. 46.7% of the Control group) (p=0845). 60.0% of the Control group subjects strongly agreed that they feel exhilarated after working closely with their clients, however, only 5.0% of the ORL subjects strongly agreed with this statement (p<0.001). 40.0% of the Control group subjects strongly agreed and 46.7% agreed that they have accomplished many worthwhile things in their job, however, only 6.2% of the ORL group strongly agreed with the statement (p<0.001), but 32.5% of the ORL group subjects agreed that they have accomplished many worthwhile things in their job (p=0.169). 60.0% of the Control group subjects strongly agreed that in their work they deal with emotional problems very calmly, whereas only 3.7% of the ORL group subjects strongly agreed with the statement (p<0.001).

Professional burnout

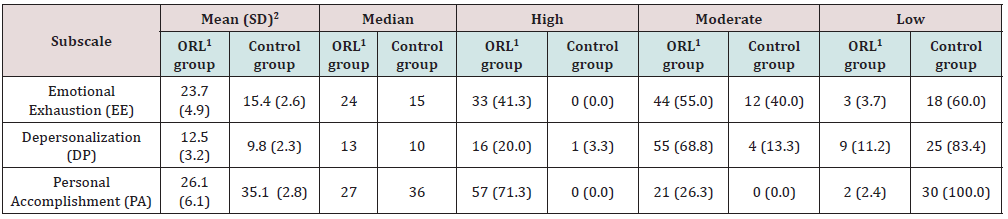

Using Maslach’s three subscales of burnout, 41.3%, 20.0%, and 71.3% of the ORL group subjects experienced a high incidence of professional burnout via EE, DP, and PA subscales, respectively. In addition, the incidence of moderate professional burnout was observed in 55.0%, 68.8%, and 26.3% of ORL group subjects via EE, DP, and PA subscales, respectively (Table 4). According to Maslach high burnout category, in the ORL group, 30 (37.5%) participants were burned out in only one of the subscales, 31 (38.8%) were burned out in two subscales, 5 (6.3%) were burned out in all three subscales, while 14 (17.5%) had no high category on any of the subscales. To conclude, in the ORL group 66 (82.5%) out of the 80 participants were classified as experiencing a high level of burnout in at least one of the subscales. Professional burnout was defined for subjects who had a high score in either the EE or DP subscale or both, which resulted in 51.3% of the ORL group subjects. However, in the Control group, only 1 subject had a high-level burnout out and it was only in one of the subscales (DP) (p<0.001) (Table 4). The distribution of the results according to the 22-item MBI is presented in Supplemental data files (Table 1).

Table 4: Distribution of Burnout subscales according to adjusted normative categories in both groups.

Correlation between MBI subscale scores and sociodemographic characteristics

Depersonalization and a high incidence of burnout syndrome were more frequently detected with increasing age in the ORL group (r=0.2, p<0.04). In addition, greater satisfaction with salary resulted in lower burnout incidence (r=0.31, p=0.001). Also, greater satisfaction with the work environment resulted in a lower burnout rate (r=0.32, p=0.001). No significant associations of the response rate in respect to other factors were determined.

Discussion

This study is the first study that addressed burnout of Lithuanian otorhinolaryngologists during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, no studies focusing on the prevalence of burnout syndrome among Lithuanian otorhinolaryngologists were performed before. The findings of this study support the concern that otorhinolaryngologists are experiencing a high-level burnout – the prevalence of burnout was 51.3%. Furthermore, in terms of the three subscales, MBI more than one-third (41.3%) reported high emotional exhaustion, one-fifth (20.0%) reported high depersonalization while almost three quarters (71.3%) experienced highly reduced personal accomplishment. In addition, 82.5% of the ORL group subjects were classified as experiencing a high level of burnout in at least one of the subscales. This data is very essential since otorhinolaryngologists are the specialists that have a direct touch with the COVID-19 and COVID-19 pandemic remains a global health system crisis with mutated SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus resulting in different variants of the virus. The results of studies analyzing burnout among otorhinolaryngologists during the COVID-19 pandemic are alarming. Civantos et al. analyzed mental health among otorhinolaryngologists and attending physicians during the Covid-19 pandemic using single-item Mini-Z Burnout Assessment, 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale, 15-item Impact of Event Scale, and 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire and reported that burnout was in 21,8% of physicians, respectively8. In addition, Civantos et al. also analyzed mental health among head and neck surgeons in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic using the same instruments and confirmed an incidence of burnout in 14.7% of physicians [26]. Another study performed by Momin et al. surveyed the Texas Association of Otorhinolaryngology to evaluate burnout. It was concluded that 50% of participants disclosed COVID-19 and the resulting changes contributed to physician burnout in their practice [27]. Larson et al. analyzed the prevalence of an association with distress and professional burnout among otorhinolaryngologists. In their study, an abbreviated 2-item version of MBI was developed and validated. It was clarified that professional burnout was present in 49% of otorhinolaryngologists [28]. However, there are still no studies analyzing burnout using three subscales 22-item MBI among otorhinolaryngologists during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Studies analyzing burnout using 22-item MBI among otorhinolaryngologists before pandemic also require attention. In 2019, Attopuls et al. also analyzed the burnout of otorhinolaryngologists in Australia and disclosed that 73.3% of correspondents suffered from burnout in at least one of the three MBI subscales [29]. The results of the previous study representing that 82.5% of the ORL group subjects experienced a high level of burnout in at least one of the MBI subscales are very similar. Moreover, our results are similar to other studies conducted in Europe. Vijendren et al. investigated professional burnout among otorhinolaryngologists in the United Kingdom (UK) and found high incidence rates of stress and psychological morbidity (56.5%) and professional burnout prevalence (28.9%) [30]. However, in their study, the authors used The General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12) and a 9-item abbreviation of the original 22-item MBI. A study conducted by Golub et al. among the United States academic otolaryngologists demonstrated that burnout was common among academic otolaryngologists [31]. In their study, they used a 22- item MBI and revealed that a high level of burnout was observed in 4% and moderate burnout in 66% of the respondents. Also, it was found out that women experienced a statistically significantly higher level of emotional exhaustion (EE) when compared to men. In addition, associate professors were significantly more burned out than full professors. In this study, we did not find any significant differences in professional burnout between men and women, nor were doctors appointed according to sub-specializations, and no respondents working in private and public medical institutions were distinguished.

Analyzing the factors that may have influenced professional burnout, a study by Fletcher et al. was conducted [32]. It was indicated that young age, number of hours worked per week, and length of time in practice are statistically significant predictors of burnout. Another study conducted among residents of otorhinolaryngology in 2020 disclosed that the increased number of working hours was confirmed to result in an upsurge of burnout using MBI [33].

Our study has also established that long working hours have a significant effect on the onset of professional burnout; however, it is also disclosed that older rather than younger age has an essential effect on the development of professional burnout. This may have been since the majority of respondents were older and only a small number of resident physicians participated in the study. Other sociodemographic factors included in this study didn’t have any significant effect on professional burnout. However, this study clarified that depersonalization (DP) and burnout syndrome were more frequently detected with increasing age in the ORL group (r=0.2, p<0.04). In this study, it was revealed that many otorhinolaryngologists (71.3%) were frustrated with their personal accomplishment at work, whereas in a study conducted by Contag et al. otorhinolaryngologists experienced moderate professional burnout but indicated high levels of personal achievement (62%) [34]. These conflicting results could be explained that this study was performed during the global pandemic situation and that in our study operating otorhinolaryngologists were included. Also, according to this study, it was clarified that low salary and an unfavorable work environment had a great impact on the burnout of otorhinolaryngologists in Lithuania. Considering why this factor could be so significantly related to professional burnout it is possible to state that the importance of salaries may be related to the economic situation in Lithuania. The strength of this study was the careful selection of investigated groups (both groups were adjusted for age, sex; also, the ORL group involved different profiles of otorhinolaryngologists). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing burnout using three subscales 22-item MBI among otorhinolaryngologists during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, this study revealed alarming results of the prevalence of burnout among Lithuanian otorhinolaryngologists, suggesting that they should start adapting their lifestyle and professional habits as soon as possible to recover from burnout.

Conclusions

This is the first study to measure burnout syndrome among otorhinolaryngologists in Lithuania which revealed that professional burnout among Lithuanian otorhinolaryngologists during the COVID-19 pandemic is high. This study identified that sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, working environment, and salary are significantly related to the prevalence of professional burnout. However, in each country, the causes of professional burnout vary depending on the age, economic situation, and professional prospects of subjects. We believe that the presented results may contribute to lessening professional burnout among otorhinolaryngologists in Lithuania.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: The author(s) declare none.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines on human experimentation (Kaunas Regional Bioethics Committee, for Biomedical Research Lithuanian University of Health Sciences (LUHS) (Approval No. BE 2-2) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

References

- Maison D, Jaworska D, Adamczyk D (2021) The challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and the way people deal with them. A qualitative longitudinal study. PLoS One 16: 1-17

- Krajewska J, Krajewski W, Zub K (2020) COVID-19 in otolaryngologist practice: A review of current knowledge. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 277: 1885-1897.

- Kumar S (2016) Burnout and doctors: Prevalence, prevention and intervention. Health 4: 37.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP (1986) Maslach Burnout Inventory. Palo Alto, CA, Consulting psychologists press, USA pp. 3463-346

- Maslach C, Leiter MP, Schaufeli W (2009) Measuring Burnout. The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well Being, USA pp. 86-108.

- Lee RT, Ashforth BE (1990) On the Meaning of Maslach’s Three Dimensions of Burnout. J Appl Psychol 75: 743-747.

- Kaschka WP, Korczak D, Broich K (2011) Burnout: A fashionable diagnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 108: 781-787.

- Civantos AM, Byrnes Y, Chang C (2020) Mental health among otolaryngology resident and attending physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: National study. Head Neck 42: 1597-1609.

- Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA (2018) Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA 320: 1131-1150.

- Salvagioni DAJ, Melanda FN, Mesas AE (2017) Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One 12: 1-29.

- Reith TP (2018) Burnout in United States Healthcare Professionals: A Narrative Review. Cureus 10: e3681.

- Mikalauskas A, Benetis R, Širvinskas E (2018) Burnout among anesthetists and intensive care physicians. Open Med 13: 105-112.

- Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Rahimzadeh M (2013) Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol Hepatol from Bed to Bench 6: 14-17.

- Konstantina Vasileiou, Julie Barnett, Susan Thorpe (2018) Characterizing and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol 18: 1-18.

- Poghosyan L, Aiken LH, Sloane DM (2009) Factor structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Int J Nurs Stud 46: 894-902.

- Žutautienė R, Radišauskas R, Kaliniene G (2020) The prevalence of burnout and its associations with psychosocial work environment among kaunas region (Lithuania) hospitals’ physicians. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 3739.

- Skorobogatova N, Žemaitiene N, Šmigelskas K (2017) Professional burnout and concurrent health complaints in neonatal nursing. Open Med 12: 328-334.

- Sachdev SB, Verma HV (2004) Relative importance of service quality dimensions: A multisectional study. J services research 4: 93.

- Bouranta N, Chitiris L, Paravantis J (2009) The relationship between internal and external service quality. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 21: 275-293.

- Maciulyte A (2016) Assessment of burnout syndrome influencing factors among doctors providing medical care. Master Thesis. Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania.

- Grunfeld E, Whelan TJ, Zitzelsberger L (2000) Cancer care workers in Ontario: Prevalence of burnout, job stress and job satisfaction. CMAJ 163: 166-169.

- Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W (2014) Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 64: 279-286.

- Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA (1995) Burnout and psychiatric disorder among cancer clinicians. Br J Cancer 71: 1263-1269.

- Tironi MOS, Teles JMM, De Souza Barros D (2016) Prevalence of burnout syndrome in intensivist doctors in five Brazilian capitals. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 28: 270-277.

- Brady KJS, Ni P, Sheldrick RC (2020) Describing the emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment symptoms associated with Maslach Burnout Inventory subscale scores in US physicians: An item response theory analysis. J Patient-Reported Outcomes 4: 42.

- Civantos AM, Bertelli A, Gonçalves A (2020) Mental health among head and neck surgeons in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national study. Am J Otolaryngol 41: 102694.

- Momin N, Nguyen J, McKinnon B (2021) Effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the Practice of Otolaryngology. South Med J 114: 327-333.

- Larson DP, Carlson ML, Lohse CM (2021) Prevalence of and associations with distress and professional burnout among otolaryngologists: Part I, Trainees. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg, United States 164: 1019-1029.

- Raftopulos M, Wong EH, Stewart TE (2019) Occupational Burnout among Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Trainees in Australia. Otolaryngol neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol Neck Surg 160: 472-479.

- Vijendren A, Yung M, Shiralkar U (2018) Are ENT surgeons in the UK at risk of stress, psychological morbidities and burnout? A national questionnaire surveys. Surgeon 16: 12-19.

- Golub JS, Johns MM, Weiss PS (2008) Burnout in academic faculty of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope 118: 1951-1956.

- Fletcher AM, Pagedar N, Smith RJH (2012) Factors correlating with burnout in practicing otolaryngologists. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg 14: 234-239.

- Reed L, Mamidala M, Stocks R (2020) Factors Correlating to Burnout among Otolaryngology Residents. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 129: 599-604.

- Contag SP, Golub JS, Teknos TN (2010) Professional burnout among microvascular and reconstructive free-flap head and neck surgeons in the United States. Arch Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg 136: 950-956.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...