Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Mini Review(ISSN: 2641-1709)

A Retrospective Study and Analysis of MRI Utility in Diagnosis of Vestibular Schwannoma Volume 7 - Issue 4

Adam Sonnenberg1,2, David Wilson3,4, Alexa Kozak3 and Kenneth M Grundfast4*

- 1Department of Systems Engineering, Boston University, USA

- 2Carle Illinois School of Medicine, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Urbana-Champaign, USA

- 3Department of Otolaryngology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston University, USA

- 4Department of Surgery, University of Connecticut Health, USA

Received: November 15, 2021; Published: November 14, 2021

Corresponding author: Kenneth M Grundfast, Department of Otolaryngology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston University, Boston, MA, 02118 USA

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2021.07.000268

Abstract

Objectives: More gadolinium enhanced MRI (MRI) scan are likely being requested than are necessary in the work up for Vestibular

Schwannoma. There are many reasons why otolaryngologists have such a low threshold for requesting MRI scans but there

likely are factors that can be used to better determine which patients with asymmetric SNHL are more or less likely to have a vestibular

schwannoma.

Study Design: A retrospective chart review of patients with hearing loss was conducted to better understand the signs and

symptoms that raise or lower suspicion of a vestibular schwannoma.

Setting: This study was conducted at Boston University’s School of Medicine.

Methods: Medical records (EMR) of 2899 patients who had audiology test results that met widely accepted criteria for diagnosis

of SNHL or were labelled as having ASNHL in reports on hearing tests that appeared in the medical record were reviewed.

Results: A statistical model was created for the purpose of differentiating, on the basis of identifiable factors, which patients

with ASNHL are more likely to have a Vestibular Schwannoma and therefore should have an MRI imaging from those patients with

ASNHL for whom a GMRI is relatively unlikely to reveal presence of a vestibular schwannoma.

Conclusions: Many GEMRI’s are being ordered as an initial screening tool for vestibular schwannoma however, evaluation of

signs and symptoms can be used to raise or lower suspicion of vestibular schwannoma in such a way as to help enable otolaryngologists

to be more judicious in deciding if MRI is the next step.

Keywords: Schwannoma; Gadolinium; ASNHL; MRI

Introduction

Often, when a patient is discovered to have asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss (ASNHL), there is concern that the patient may have a vestibular schwannoma (VS), often described as an acoustic neuroma (AN) on the side with poorer hearing. While the prevalence of vestibular schwannoma in the general population is approximately 1 in 100,000, the prevalence of VS in patients diagnosed with ASNHL has been reported to range between 2 and 8 percent [1,2]. Prior to 1985, confirming suspicion of VS as the cause of ASNHL was not easy and often involved such invasive and painful procedures as a contrast cisternogram. However, in 1986, Curati et al. [3] demonstrated that gadolinium enhanced MRI (GEMRI) is an effective method for detecting a VS. Subsequent technological advancements to GEMRI have made the technique reliable and sensitive enough to detect a VS as small as 1 or 2 mm in diameter [4] so GEMRI has become the “gold standard” diagnostic test for detection of a VS [5]. Consequently, to some extent, requesting a GEMRI has become a nearly reflexive step in the diagnostic assessment of patients known to have ASNHL. Now, more than three decades after the GEMRI became a readily available imaging study frequently utilized for assessment of patients with ASNHL, reports are demonstrating that fewer than 2% of GEMRI scans ordered to determine the cause of asymmetric SNHL actually result in the identification of a VS [6]. Furthermore, the relative necessity and urgency for early detection of VS with GEMRI may have diminished because surveillance instead of surgical resection has become an acceptable option in management of patients with ASNHL [7]. Therefore, put in perspective, now seems to be a propitious time to re-evaluate the utility and effectiveness of the GEMRI in assessment of patients with ASNHL. Much has been written about the usefulness of magnetic resonance in the identification of VS [8]. Also, studies have explored the costs associated with the clinical assessment involved in detection of a VS [9,10] but there is not yet a model to be used in determining when it is most appropriate and cost-effective to request a GMRI in the overall assessment of a patient with ASNHL. Accordingly, the electronic medical records (EMR) of 1316 patients who had audiology test results that met widely accepted criteria for diagnosis of ASNHL or were labelled as having “asymmetric hearing loss” in reports on hearing tests that appeared in the EMR were reviewed and a statistical model was created for the purpose of differentiating, on the basis of identifiable factors, which patients with ASNHL are more likely than others to have a VS and therefore are the patients for whom a GEMRI is most likely to be of diagnostic significance.

Methods

Calculating how each symptom changes the likelihood of vestibular schwannoma

After obtaining approval from the Boston Medical Center (BMC) Institutional Review Board, the EMR of 2899 patients evaluated between 2001-2014 with SNHL, defined as having ICD-9 code 389.10, who had an MRI conducted were reviewed. Excluded from the study group were the records of pediatric patients (under 18 years of age). Audiology narrative reports and audiogram displays from the remaining patients were analyzed to determine if the audiology test results met either or both of the widely accepted criteria for the diagnosis of ASNHL, the Mangham Criteria (an average interaural difference of at least 10dB at the 1-8kHz range), or the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) protocol (an average interaural difference of 15dB at the 0.5-3kHz range). Additional parameters assessed included the following: age, gender, radiologist’s interpretation of the GEMRI, and patient’s report of a history of noise exposure or concomitant, tinnitus, vertigo, disequilibrium, dizziness, facial weakness, numbness ipsilateral to the ear with poorer hearing, word recognition score, and interaural difference. Graphing and statistical analysis was performed using MATLAB, and Sigma Plot. To determine which symptoms presented at statistically significant rates for the VS group and the no VS group, a binomial distribution was used to calculate the standard deviation and mean of each symptom’s rates each group. A two-proportion z-test was then used to calculate the test statistic (z-score) of each symptom.

Results

Overview of Electronic Medical Records

The asymmetry of hearing loss of was assessed and, of the 2899 records reviewed 1316 patients had hearing test results that met widely accepted criteria for ASNHL or were described as having ASNHL even though their hearing test results did not meet the accepted criteria for this diagnosis. Among the 1316 patients with ASNHL, 68 had imaging findings interpreted as being suggestive of VS. Of those who were diagnosed with VS on the basis of interpretation of GEMRI findings, only 22 eventually received a definitive therapeutic intervention, either surgery or radiation. In the group of 1583 patients with symmetrical SNHL who received MRI scans, 17 showed evidence of a VS, and none of the patients with the imaging finding consistent with VS elected to have surgery or radiation therapy most likely because their symptoms were minimal, and the detection of the VS may have been an incidental finding.

Demographic characteristics and significant symptoms

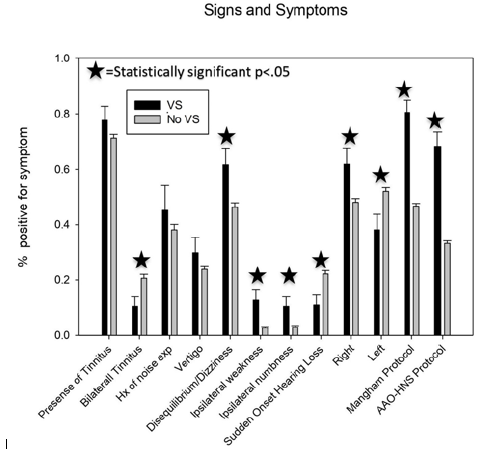

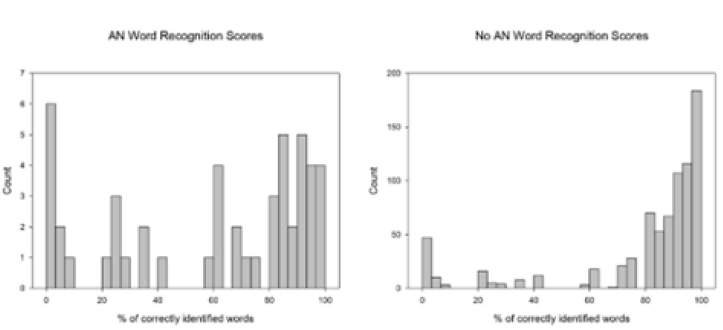

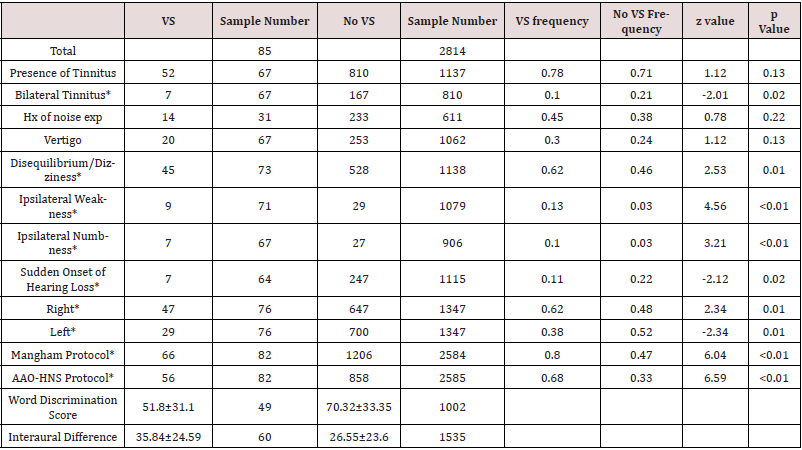

Signs and symptoms were calculated and details for all symptoms are given in Figure 1 and the distribution of word recognition scores is reported in Figure 2. Patient ages ranged from 18 to 90 years with a median of 54, and there was no significant age difference between the VS and no VS groups. The male to female ratio of the no VS group was 1.12 to 1, which was similar to the overall Group 1 at 1.14 to 1 and was lower than the ratio of the VS group at 1.9 to 1. This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.19). A significant difference between the asymmetric no VS group and the asymmetric VS group was found for the presence of bilateral tinnitus, disequilibrium/dizziness, ipsilateral weakness, ipsilateral numbness, sudden onset of hearing loss, word discrimination score<=20, and word discrimination score>=80 . A summary of all p-values and their respective means are given in Table 1. All other symptoms failed to reach a significance of 95%.

Figure 1: Signs and symptoms investigated during the study. Statistically significant symptoms have a star, and all numbers are given by percent of individuals who are positive for the symptom.

Figure 2: Histograms for the Word recognition score for both the VS and no VS groups. The VS group was more uniform while

most No VS subjects were found above 80% of correctly identified words.

Supplemental Material Legend: This supplemental information contains a mathematical formula developed as an aid to

finding a reasonable threshold for requesting an MRI scan based on a patient’s signs and symptoms. Also include here is a

cost analysis that can be used to provide information about the financial impact of requesting an MRI scan for a patient with

asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss.

Table 1: Overview of all signs and symptoms investigated in the study.

P value between the two sample populations is also reported in the final column.

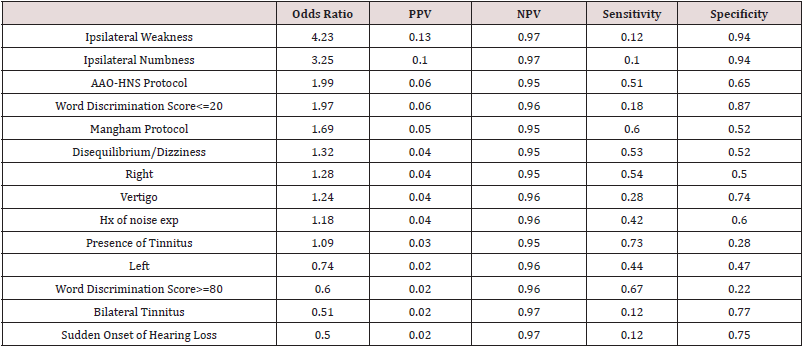

The power of audiometric findings

Both the Mangham criteria and the AAO-HNS criteria proved to have the strongest difference between the VS and no VS group based on the calculated p values in Table 1 however, applying either of the criteria did not reliably correlate with identification of a VS when odds ratios are considered. A word discrimination score less than 20% was just about as useful as meeting the AAO-HNS criteria and slightly more useful than meeting the Mangham criteria for ASNHL based on calculated odds ratios. Presence of ipsilateral facial weakness and ipsilateral facial numbness was the strongest indicator of finding a VS. Odds ratios, PPV, NPV, Sensitivity, and Specificity are reported in Table 2. The probability of finding a VS in the poorer hearing ear in the ASNHL population before any symptom is observed, was 4.4%, which is consistent with previous studies that report the percent to be between 2% and 8% [1,2,6]. Using a conditional probability method, the probability of finding a VS given a yes response to each symptom was calculated. The results of each tests change to the probability is given by the PPV in Table 2.

Table 2: Insightful statistics into the power of each statistically significant symptom.

PPV stands for positive predictive value while NPV is negative predictive value.

Discussion

Most VS’s grow slowly and hearing preservation with surgical

excision is difficult to achieve. Focused radiation therapy is effective

for managing some patients with VS, and the relative necessity

of obtaining a GEMRI as soon as a patient has been diagnosed

with ASNHL may mean that otolaryngologists and others involved

in the assessment of patients with ASNHL could be more selective

in deciding which patients diagnosed with ASNHL should have a

GEMRI. This study may overestimate the value of early detection of

a VS considering that many patients will not receive the benefit of

having their hearing saved. It is worth noting that using asymmetry

of hearing thresholds alone as the indication for requesting a

GEMRI would miss almost 20% of the VS patients included in the

study. An additional limitation to the cost-effective model is that it is based solely on GMRI costs. Many centers perform high resolution

T2 scans, that may alter costs associated with finding a VS. For

example, if cost could be reduced the threshold for when it would

be cost effective to scan for a VS could be lower. A discussion of how

cost could play a role in the decision-making process for VS was

conducted as is in the supplemental text. In this current era of cost

containment in health care and the burgeoning array of accountable

care organizations, now is a good time to assess the utility and

cost-effectiveness of the GEMRI in the assessment of persons who

have hearing thresholds that are not the same in each ear. Possibly,

more GEMRI’s are being requested than may be necessary.

There are many reasons why otolaryngologists and others

seem to have such a low threshold for requesting GEMRI scans including

apprehension about being sued for missing a diagnosis of

a VS. However, there likely are factors that can be used to better

determine which patients with asymmetric SNHL are more or less

likely to have a VS as the cause for the asymmetry. Although the

foibles of a retrospective study make it difficult to draw definitive

conclusions, based on observations made in our study, we do have

the suggestions that follow. If audiologists and otolaryngologists

were to adhere strictly to the widely accepted specific criteria when

describing and labelling a difference between ears as “asymmetric”

then this might decrease the tendency for requesting a GEMRI

whenever the word asymmetric is seen in the written summary of

hearing test results. With advances in test techniques and computer

analysis of test results, and, depending on the severity of the

hearing loss, auditory brainstem tests (ABR) might be used as an

intermediary step to raise or lower suspicion of likelihood that a

patient has a VS, and, in turn, be used to help decide if a GEMRI is indicated5,11.

However, it is worth mentioning, that additional tests

such as ABR would raise the cost of detecting a VS. While MRI has a

much higher predictive value, and has been proposed as more cost

effective [11], ABR may prove to be a useful tool in the diagnostic

workup. An alternative to reflexively requesting a GEMRI for all patients

who have worse hearing in one ear might be to defer GEMRI

and repeat the hearing test in 6-12 months. Deferring a request for

a GEMRI might be reasonable in patients with poorer hearing in

one ear who have no significant abnormal findings in the otoneurologic

exam, but they manifest any of the characteristics that follow

below:

a) A history consistent with excessive noise exposure specifically

in the poorer hearing ear

b) A history of having had labyrinthitis in the poorer hearing

ear

c) A history of having had surgery in the poorer hearing ear

d) Word discrimination score that is greater than 80% in the

poorer hearing ear

e) Age 70 years or older

f) If a patient has ASNHL and a history of tinnitus, facial

weakness or facial twitching ipsilateral to the worse hearing

ear and/or symptoms of disequilibrium, then a GEMRI is probably

indicated.

g) If a patient has ASNHL and speech discrimination scores

that are worse than what would be expected based on the

Speech Reception Threshold (SRT) and the Pure Tone Average

(PTA), then a GEMRI probably is indicated.

Emerging evidence suggests that there might be an approach

to utilizing GEMRI for detection of VS in a way more rational and

cost-effective than the way that GEMRI is currently being used for

assessment of patients presenting with ASNHL. Further, it is worth

noting that ASNHL is not the only early indicator that a patient

might have a VS. In our study, we found that 16 out of 84, or 19.04%,

of the total number of patients diagnosed with VS, had hearing test

results that did not meet either the Mangham or AAO-HNS criteria

for diagnosis of ASNHL. Of note, the symptoms typically associated

with vestibular schwannoma such as tinnitus, vertigo and

facial numbness/weakness were not consistently recorded in EMR

notation describing the history of present illness nor consistently

reported among findings in the physical examination. Further, it

seems from our review of EMR that those writing notes in the record

may have confused facial numbness with facial weakness because

descriptions of abnormal facial movement sometimes were

accompanied by a description of “facial numbness”. Considering

that it seems that some patients who are described in an EMR note

as having an “asymmetric” SNHL, do not meet the widely accepted

criteria for having a diagnosis of asymmetric sensorineural hearing

loss. In turn, this can be a source of confusion, perhaps leading to an

impetus to request MRI scans that may not need to be done.

Lack of precise descriptions in the EMR pertaining to important

aspects of history taking and physical exam could skew in our

analysis the diagnostic significance attributed to certain symptoms

and exam findings. Omission or lack of documentation about symptoms

traditionally known to be associated with diagnosis of VS and

inconsistency between an audiologist’s written report of audiometric

findings and a physician’s interpretation about the significance

of audiology test results was detected with concerning frequency.

Two factors helpful in medical decision making but were most often

not mentioned in the medical record (NMITMR) were history of

noise exposure and laterality of tinnitus. NMITMR for the study is

shown in Table 1. Of note, roughly half of the patients whose clinicians

elected to pursue monitoring instead of imaging were subsequently

lost to follow up. This high attrition rate could potentially

reduce the sensitivity of a focused workup strategy. In this study, a

history of sudden onset hearing loss was associated with a lower

risk of having a vestibular schwannoma, but not at statically significant

rates. This is consistent with the known fact that VS usually

causes slowly progressive SNHL rather than the sudden hearing

loss that is idiopathic. It is notable that neither the Mangham nor

the AAO-HNS criteria considers the magnitude of asymmetry of

hearing loss. It is likely that patients with VSs have a larger interaural

difference compared to no VS patient, even after considering

baseline random interaural variations. With the Mangham criteria

significantly higher than the no VS group, and that there were also

more patients with differences in the 20-40 dB range and fewer in the normal variance range of less than 20 dB. The results and more

can be seen in Table 1.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has shown that many GEMRI’s are being ordered as an initial screening tool for AN. However, it seems that careful evaluation of audiology test results could be used to raise or lower suspicion of AN in such a way as to help enable otolaryngologists to be more judicious in deciding whether or not requesting a GEMRI is the best next step in case management. Relying too heavily on symmetry of hearing loss could have the result of missing a diagnosis of AN in some patients. Possibly, in the future, fewer GEMRIs might be needed in the assessment of patients with ASNHL. For now, incorporation of multiple signs and symptoms in the diagnostic process should lower false negative rates when screening for VS. One easy step that might be taken to help improve the utility and cost-effectiveness of GEMRI in the evaluation of patients with ASNHL would be for audiologists and otolaryngologists to refrain from using the ICD-10 diagnostic code for asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss if a patient has audiologic findings that show a difference in pure tone thresholds between two ears but the audiologic test results do not meet either the AAO-HNS or the Mangham criteria for diagnosis of ASNHL. Once strict criteria for diagnosis of ASNHL are utilized, then consideration of several factors in the medical history and physical examination could be used effectively to raise or lower suspicion that a patient with ASNHL has a VS. In turn, assessment of these signs and symptoms could be used to help decide whether an MRI is likely or unlikely to reveal presence of a VS. Based on this study, relying too heavily on ASNHL diagnosis actually increases the risk of falsely dismissing a patient with a VS.

Acknowledgements

Minhtran Ngo, Jillian Trieff, and Kunal Shetty are thanked for their assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded in part by Boston University School of Medicine. The work was conducted at Boston medical center.

Contributions

Adam Sonnenberg: Data analysis, figures, manuscript editing

and preparation.

Alexa Kozak: Manuscript editing and preparation.

David Wilson: IRB approval, data collection, manuscript editing

and preparation.

Kenneth Grundfast: IRB approval, principal investigator, manuscript

editing and preparation.

References

- Ahsan SF, Standring R, Osborn DA, Peterson E, Seidman M, et al. (2015) Clinical predictors of abnormal magnetic resonance imaging findings in patients with asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 141(5): 451-456.

- Kesser BW (2010) Clinical thresholds for when to test for retrocochlear lesions: con. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136(7): 727-729.

- Curati WL, Graif M, Kingsley DPE, King T, Scholtz CL, et al. (1986) MRI in acoustic neuroma: a review of 35 patients. Neuroradiology 28(3): 208-214.

- Marx SV, Langman AW, Crane RC (1999) Accuracy of fast spin echo magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of vestibular schwannoma. Am J Otolaryngol 20(4): 211-216.

- Wilson DF, Hodgson RS, Gustafson MF, Hogue S, Mills L (1992) The sensitivity of auditory brainstem response testing in small acoustic neuromas. Laryngoscope 102(9): 961-964.

- Jiang ZY, Mhoon E, Saadia-Redleaf M (2011) Medicolegal concerns among neurotologists in ordering MRIs for idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss and asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss. Otol Neurotol 32(3): 403-405.

- Quesnel AM, McKenna MJ (2011) Current strategies in management of intracanalicular vestibular schwannoma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 19(5): 335-340.

- Fortnum H, O’Neill C, Taylor R (2009) The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the identification of suspected acoustic neuroma: a systematic review of clinical and cost effectiveness and natural history. Health Technol Assess 13(18): 3-4,9-11.

- Wilson YL, Gandolfi MM, Ahn IE, Yu G, Huang TC, et al. (2010) Cost analysis of asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss investigations. Laryngoscope 120(9): 1832-1836.

- Crowson MG, Rocke DJ, Hoang JK, Weissman JL, Kaylie DM (2017) Cost-effectiveness analysis of a non-contrast screening MRI protocol for vestibular schwannoma in patients with asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss. Neuroradiology 59(8): 727-736.

- Rafique I, Wennervaldt K, Melchiors J, Caye-Thomasen P (2016) Auditory brainstem response - a valid and cost-effective screening tool for vestibular schwannoma? Acta Otolaryngol 136(7): 660-662.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...