Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-6003

Research Article(ISSN: 2638-6003)

The Study Plays Fighting to Cope with Children Aggression at Primary School Volume 2 - Issue 2

Dao Chanh Thuc*

- Department of Physical Education, AN GIANG University, Vietnam

Received: November 21, 2018 Published: November 27, 2018

Corresponding author: Dao Chanh Thuc, Department of Physical Education, Vietnam

DOI: 10.32474/OSMOAJ.2018.02.000134

Abstract

Aggressive behaviour among young people represent a universal concern and many children and adolescents report having been victimized or having bullied others. Cost-effective strategies are required to cope with this problem. The present study investigated the effect of play fighting on self-perceived aggression at primary school pupils. Using a crossover longitudinal design, 63 fourth and fifth-grade pupils (31 boys and 32 girls, mean age = 9.6 ± 0.5 years) took part in a controlled play fighting school-based intervention 2 days/week for 4 consecutive weeks, replicating the program adopted in a previous study with 13-year old junior high school students. Participants filled in the 12-item short version of the Aggression Questionnaire three times: baseline period (A0 and A1), and after the go fighting intervention (A2). A RM-ANOVA showed significant within subject differences among the three evaluation times (F=2.91, P = 0.003). At A1 Verbal Aggression, Anger, and Hostility significantly decreased, while at the post-intervention, only Physical Aggression was significantly lower in comparison with A1 (A1 = 5.45 ± 2.47; A2 = 5.04 ± 2.41; F = 5.22, p = 0.005). Results provide some preliminary insight on the role that play fighting can have as a part of a physical education curriculum to cope with children antisocial and aggressive behaviour, confirming the encouraging conclusions of previous research in young adolescents.

Keywords: Aggressive Behaviour; Children; Peer-Aggression; Physical Education; Play Fighting

Introduction

Aggressive behaviour among young people represent a global concern and a considerable number of children and adolescent report having been victimized or having bullied others [1]. In Vietnam, the country where this study was conducted, it has been estimated that 45.5% of girls and 46.7% of boys aged 10-16 reported having been a victim in some offensive, disrespectful and/ or violent episodes in the previous 12 months.

There is an urgent need for action to cope with aggressive behaviour and prevent their repetition among youths, and costeffective strategies are required. Emerging evidence suggests that health-related interventions (e.g. physical education and organized sports) may have consistent effects on a range of social and psychological outcomes linked with peer aggression [2]. The school context, especially physical education lessons, can provide an ideal setting to recognize and address children and adolescents’ socioemotional and behavioral problems [3,4]. Physical education and organized sport have been proved to have positive effects on antisocial and prosocial behaviours [5]. In particular, programmed based on physical activities involving significant amounts of physical contact, such as go fighting, have been reported providing meaningful experiences in the emotional and social domains.

Go fighting is a physical activity, often vigorous, intense and rough, which requires very physical ways of interacting and learning by means of patterns such as running and chasing, fleeing, grappling, kicking, wrestling, open-palm tagging, swinging around and falling to the ground often on the top of each other [1]. Play fighting may look like but does not generally involve, real fighting [6]. This play also requires children to alternate and change roles and these successful social conversations and interactions can provide children with social knowledge, cognitive performance and emotional development [7,8]. Go fighting can be considered a structured form of the rough-and-tumble play that is spontaneous during childhood [9]. The fight is a primary instinct and Lapierre and Aucouturier [10] defined it as the motivation and the primary instinct of all human activity. Aggressive instinctual drives cannot be eliminated, but they should be controlled and expressed in socially acceptable behaviours [3,4]. To play fight, players have to assume inherently fair behaviour: they can play rough without injury only when able to control excessive physical aggression, to respect the opponent and the rules of the game [11]. Educating the expression of these feelings gives pupils the chance to behave consciously in a regulated and safe environment, and this teaches them to control their aggressive impulses and to have respect for others.

Although few studies have discussed the effects of teaching play fighting, particularly within the school setting, there is evidence suggesting that this form of exercise may reduce the aggressive behaviours of participants [1]. The proposed mechanism explaining this reduction is that participating in non-threatening contact experiences, which are a core-part of go fighting, can help players to reduce the probability of interpreting ambiguous actions as threatening [12]. Using a cross-over longitudinal design, the present study examined self-reported aggression in a group of 4th and 5th -grade primary school pupils at the baseline and after eight classes go fighting school-based programme.

Materials & Methods

A fourth and a fifth-grade classroom (38 boys, 36 girls, mean age = 9.6 ± 0.5 years) took part in the study. After data cleaning, 63 pupils (31 boys and 32 girls) were included in the analysis, 11 were excluded due to incomplete evaluation (children were absent in one of the days when data were collected). The 12-item short version of the Aggression Questionnaire [13] was used. It consists of four 3-item subscales (Physical Aggression, Verbal Aggression, Anger, and Hostility) derived from the 29-item AQ [14], that is one of the most popular self-report measures of aggression. Participants were asked to rate each item on a scale from 1 (Not at all like me) to 5 (Completely like me), with higher scores indicating higher selfreported aggression.

After receiving the Ethics Committee and the school principal approval, parents were informed about the research aim and signed a written informed consent prior to the enrollment in the study of their children. All the participants filled in the 12-item AQ three times in total: two times before the intervention (baseline condition, A0-A1), then at the end of the interventions (A2). The questionnaire was self-completed by students in the classroom with the supervision of the class teacher and a researcher that can assist children if needed. A trained researcher conducted the play fighting activities during the scheduled 2-hour/week physical education lessons, classroom teachers assisted in the intervention. In total 8 classes of play fighting were proposed during 4 consecutive weeks (A1-A2 period of intervention), replicating the program adopted in a previous study with 13-year old junior high school students [1]. The lessons took place in the school gym, using mats to prevent hurts falling down. The intervention consisted in a progression of games and exercises that gradually involved pupils in a progressively greater physical confrontation with big body play, exercises and movement situations based on running and chasing, fleeing, kicking, grappling and wrestling Statistical Analysis Means, standard deviations, and Cronbach alpha were calculated for each of the AQ four subscales.

Independent sample t-test was performed to assess the differences between the two classrooms and between boys and girls. Since no significant differences between the two classrooms nor by gender were found at A0, a repeated measure ANOVA (RMANOVA) was used to test differences within subjects on all the subscales of the AQ in the three evaluation times (A0, A1, and A2). A multiple comparison analysis has been conducted as posthoc. Level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

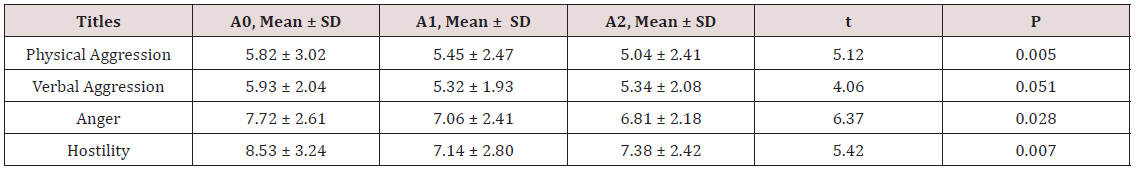

Cronbach’s alphas for the four subscales were respectively: Physical Aggression α=.69, Verbal Aggression α=.58, Anger α=.61, and Hostility α=.69. Cronbach’s alpha values for Verbal Aggression and Anger were the lowest, this is in line with previous results reported by Ang RP [15] with Asian adolescents, and those reported by Carraro [1] with Italian young adolescents. The RM-ANOVA showed significant within-subject differences among the three evaluation times (F=2.91, p =0.005) (Table 1). Between A0 and A1, the multiple comparison tests showed decreased Verbal Aggression (p =0.051), Anger (p = 0.028), and Hostility (p = 0.007). In the A1- A2 comparison, while mean values of all the subscales were slightly lowered, only Physical Aggression significantly decreased (p = 0.025).

Discussion

This study involved 63 students in grades four and five who analyzed the effectiveness of a short-term combat program as part of a self-reported physical education program. The results show that schools typically affect some aspects of self-reported aggression: participants significantly reduce aggression, hostility and anger and this can be explained with the mission. the education that the school outperforms the academic achievement of the student. However, only after introducing the fight at the school’s physical education program, participants reported a significant decline in physical aggression. As expected, results are in line with those reported by Carraro [1] and seem to confirm the hypothesis that play fighting, in a controlled, structured school setting, can facilitate the control over aggressive impulses [16]. In particular, by go fighting, children can learn through direct experience how to control themselves and to manage physical strength through bodily contact, which may be potentially harmful or offensive.

Conclusion

The present study has several limitations that do not allow for generalization of the findings, in particular: the single group study design, the limited duration of the programme (4 consecutive weeks), the use of self-reported measures, the limited number of participants and the absence of follow-up measures. However, results may provide some suggestions for future studies with longer duration and larger samples or in schools where peer aggression represents a serious concern, and for studies combining selfreport measures with structured observation. Teaching go fighting to primary school pupils requires appropriate methodology, adequate supervision, and clear rules to guide the play, so as creating a positive educational setting and to avoid problems related to excessive aggressive behaviours. Not only physical education teachers but also special education teachers may receive information on this topic and could be specifically trained to teach these activities to facilitate inclusion [17,18]. The positive effect of play fighting on peer aggression could also benefit interpersonal relationship outside the physical education context and in turn emphasise inclusion in school [1].

Research into the effects of go fighting on aggressive behaviours in youths is still scant [1]. The current results provide some preliminary insight on the role that these activities can have among children as a part of a school physical education curriculum, to increase the social and emotional learning.

References

- Carraro A, Gobbi E (2018) Play fighting to cope with children aggression: A study in primary school. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 18(3): 1455-1458.

- Wilson DK (2015) Behavior matters: The relevance, impact, and reach of behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 49(1): 40-48.

- Gobbi E, Carraro A (2017) Play fighting as a strategy to cope with aggressive behaviours among youth with social disadvantages in Italy. In: AJS Morin, C Maïano, D Tracey, RG Craven (Eds); Inclusive physical activities: International perspectives. Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing Inc, pp. 163-182.

- Thuc DC (2017) Go fighting as a strategy to cope with aggressive behaviours among youth with social disadvantages in Vietnam. Journal sport science 23(1): 113-122.

- Rutten EA, Stams GJJ, Biesta GJ, Schuengel C, Dirks E, et al. (2007) The contribution of organized youth sport to antisocial and prosocial behavior in adolescent athletes. Journal of youth and adolescence 36(3): 255-264.

- Schåfer M, Smith PK (1996) Teachers’ perceptions of play fighting and real fighting in primary school. Educational Research 38(2): 173-181.

- Pellegrini AD, Smith PK (1998) Physical activity play: The nature and function of a neglected aspect of play. Child development 69(3): 577- 598.

- Huynh TK (2003) The nature and function of physical activity in a neglected aspect of the game to the development of the child. Journal sport science 9(1): 177-198.

- Lillard AS, Lerner MD, Hopkins EJ, Dore RA, Smith ED, et al. (2013) The impact of pretend play on children’s development: A review of the evidence. Psychological bulletin 139(1): 1-34.

- Lapierre A, Aucouturier B (2001) La symbolique du mouvement. Psychomotricité et éducation. Paris: EPI, p. 1-9.

- Olivier JC (1995) La lutte a l’ecole. Paris: Nathan.

- Hernandez J, Anderson KB (2015) Internal martial arts training and the reduction of hostility and aggression in martial arts students. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research 20(3): 169-176.

- Bryant FB, Smith BD (2001) Refining the architecture of aggression: A measurement model for the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality 35(2): 138-167.

- Buss AH, Perry M (1992) The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63(3): 452-459.

- Ang RP (2007) Factor structure of the 12-item aggression questionnaire: Further evidence from Asian adolescent samples. Journal of Adolescence 30(4): 671-685.

- Kirsh SJ (2006) Children, adolescents, and media violence: A critical look at the research. California USA: Sage Publication, p. 11-18.

- Greguol M, Gobbi E, Carraro A (2013) Formação de professores para a educação especial: uma discussão sobre os modelos brasileiro e italiano. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, Marília 19(3): 307-324.

- Fossati A, Maffei C, Acquarini E, Di Ceglie A (2003) Multigroup confirmatory component and factor analyses of the Italian version of the Aggression Questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 19(1): 54.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...