Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-6003

Case Report(ISSN: 2638-6003)

Neglected Posterior Shoulder Dislocation with a Large Bone Defect in a young Active Patient Treated with Osteochondral Allograft Volume 4 - Issue 2

Gatti A1,2*, Primavera M1,2, Casamassima D1,2, Emanuele G1,2 and Tarantino U1,2*

- 1Department of Clinical Science and Translational Medicine, University of Rome, Italy

- 2Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Italy

Received:May 17, 2020; Published: June 15, 2020

Corresponding author: Gatti A, Department of Clinical Science and Translational Medicine, University of Rome, Italy Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Italy

DOI: 10.32474/OSMOAJ.2020.04.000182

Abstract

Background: Posterior glenohumeral joint dislocation is a rare injury. Despite positive clinical signs is often underdiagnosed and undertreated. The presence of a large bone humeral defect could worsen the outcome.

Case Report: We report a case of 45 years-old man with a neglected posterior shoulder dislocation with a large segmental bone defect involving 40% of the articular surface of the humeral head. We decided to treat the patient with an open reduction of the shoulder dislocation and reconstruction of the articular surface with fresh-frozen humeral head allograft. Our patient showed improved shoulder mobility and ROM on all planes that positively affected the patient daily activities; no pain was registered at follow-ups.

Conclusion: Our case report demonstrates that neglected posterior shoulder dislocations with a large bone defect and viable humeral head can be treated using allograft, obtaining optimal clinical results and avoiding the need for early prosthetic replacement surgery.

Keywords: Neglected Posterior Shoulder Dislocation; Reverse Hill-Sachs Lesion; High-Demand Patient; Humeral Head Allograft; Anatomic Shoulder Restoration

Abbreviations: GHJ: Glenohumeral Joint; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; MVA: Motor Vehicle Accident; LHB: Long Head Of Biceps Brachii; XR: X-Rays

Introduction

Posterior glenohumeral joint (GHJ) dislocation is a rare injury and accounts for only 2% to 5% of all dislocations of the shoulder [1]. GHJ posterior dislocation has a prevalence of 1.1 per 100,000 inhabitants per year, with the first peak in male patients aged between 20-49 years old, and the second one in the elderly over the age of seventy [2]. Posterior shoulder dislocation is often underdiagnosed and undertreated in up to 50% of cases admitted to the E.R. [3]. A dislocation is defined chronic when left untreated for more than 3 weeks. Diagnosis of posterior GHJ dislocations is often delayed, becoming chronic and leading to a locked joint and decreased functional outcome [4]. Typically, posterior shoulder dislocation can be traumatic or atraumatic: the first might be due to direct high-energy trauma or it can also develop insidiously through a repetitive minor injury. A major trauma with a force applied to the arm with the shoulder in adduction, flexion and internal rotation is the most frequent cause (e.g. A direct blow to the anterior shoulder or by a fall on a forward-flexed upper limb)[5]. On the other hand, seizures and electrocution are the major causes of atraumatic dislocations, by contraction of the internal rotators and disruption of the joint static and dynamic posterior stabilizers [1]. Associated injuries include humeral neck or tuberosity fractures, impaction fractures of the anterior humeral head (i.e. reverse Hill–Sachs lesion), posterior labrum capsular complex lesions (i.e. reverse Bankart lesion) and rotator cuff tears [2, 6]. Reverse Hill-Sachs lesions can be associated with posterior GHJ dislocation in up to 86% of cases, requiring open or arthroscopic surgical therapy [1, 7, 8].

Missed, late or incorrect diagnosis is a significant clinical problem, as it can predispose to serious complications, such as chronic instability, osteonecrosis, post-traumatic osteoarthritis, persistent joint stiffness and functional instability [4, 8]. Treatment management of chronic posterior shoulder dislocation associated with a large articular defect is strongly debated due to lack of studies with significant clinical records: operative treatment is usually preferred based on the type and the extension of injury, age, medical history and functional demand of the patient. The patient gave consent for case report.

Case Report

A 45-year-old deaf man, involved in an MVA, sustained a direct

blunt trauma to his dominant right shoulder. The patient was

employed as a warehouse worker. At the time of the accident, he

has been admitted to the ER of another hospital where he has been

discharged with the diagnosis of “right shoulder contusion”. The

patient was admitted to our clinic three months after the trauma,

complaining severe pain and functional limitation of the right

shoulder. At physical examination the patient showed functional

limitation of the shoulder motion on all planes, in particular:

abduction 30°, flexion 30°, internal rotation at the iliac spine,

external rotation 0°. At palpation the shoulder was painful. The

patient was neurovascular intact.

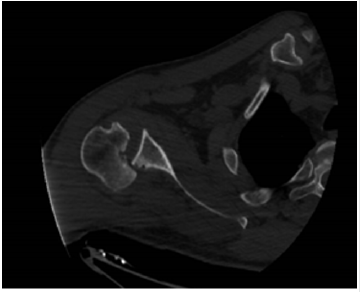

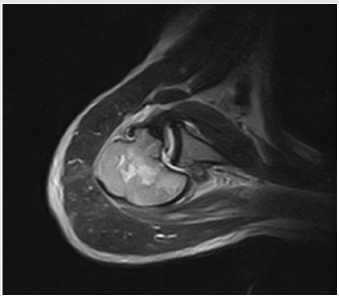

X-Ray and CT scan were carried out, showing posterior GHJ

dislocation with an osteocartilagineous lesion about 40% of the

humeral head surface, localized on its antero-medial edge (a reverse

Hill-Sachs lesion; type I according to Randelli’s classification of

posterior shoulder dislocation) (Figure 1) [9]. Based on clinical

(i.e. not reducible dislocation after conservative treatment) and

radiological evaluation (i.e. complete dislocation of the shoulder

with important bone loss of the humeral head), the patient was

subsequently scheduled for surgery. Considering the young age

of the patient, his high functional demand and the extension

of the lesion, we decided to perform a humeral head allograft

reconstruction. We requested it to the bone bank communicating

the size of the humerus of the patient to obtain the best matching

allograft. The procedure was performed under general anaesthesia

with the patient placed in a beach-chair position. A deltopectoral

approach was used with release of the pectoralis major tendon

insertion to improve the exposure of the surgical field. After

finding and isolating the anterior humeral circumflex artery and

vein, the subscapularis tendon was exposed and cut through its

insertion. After detaching the subscapularis muscle from the lesser

tuberosity, as the long head of biceps brachii (LHB) tendon tended

to dislocate from the bicipital groove we decided to tenotomize

it. We proceeded to perform lysis of the posterior adhesions and

then the posteriorly dislocated locked humeral head was gently

reduced with the aid of a Schanz pin inserted in the lateral aspect

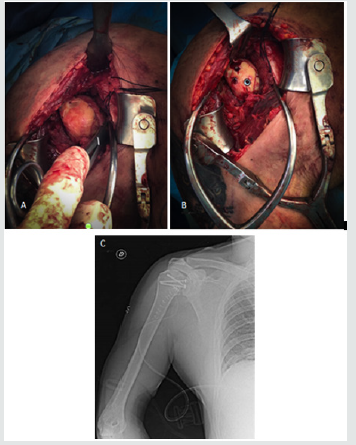

of the humeral shaft used as a joystick. Subsequently a large 40%

reverse Hill–Sachs lesion was exposed. With an appropriate burr, an

accurate regularization of the Hill-Sachs lesion was made, obtaining

a viable bony surface. The fresh-frozen humeral allograft was then

carefully prepared aside to obtain an anatomic restoration of the

cephalic anatomy. The size-matched osteocartilaginous allograft

was press-fit into the humeral defect and fixed with 3 4.0mm lag

screws reaching a stable construct – (Figure 3). The subscapularis

tendon was reinserted by two anchors (JuggerKnot® SoftAnchor

- 2.9 mm, Zimmer-Biomet, Jacksonville, FL, USA), (ALLthread™

Suture Anchor – 5mm Zimmer-Biomet, Jacksonville, FL, USA), on

his anatomical site. The LHB was sutured on the pectoralis major

tendon with non-absorbable suture. The arm was kept in a 30° of

abduction and 30° of external rotation using a shoulder brace for

4 weeks post-operatively. Passive range of motion was started at 4

weeks following surgery and active range of movement was started

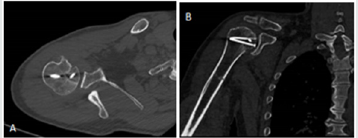

6 weeks post-operatively. A shoulder CT scan was performed at

1-year follow-up showing no signs of allograft bone resorption,

screw loosening or avascular necrosis (Figure 4 A-B). Also 1 year

after surgery the patient reported no painful symptoms showing

excellent ROM on all planes (Figure 5 A-D); he was able to perform

normal daily and work-related activities. A 95 points Constant-

Murley Score was recorded at this time.

Discussion

The aim of this paper is to present the clinical results using

a fresh-frozen osteochondral humeral head allograft in a young

active patient affected by a chronic GHJ dislocation with reverse

Hill-Sachs lesions about 40%. Scientific literature shows scarce

consensus about the treatment of this rare injury: there is an

ongoing debate about the different treatment options. Moreover

there is not an agreement on the best allograft that has to be used.

The reverse Hill-Sachs lesion size is the most influencing factor for

choosing the type of treatment [3]. The reverse Hill-Sachs (also

called McLaughlin lesion) is a wedge-shaped impaction fracture on

the antero-medial aspect of the humeral head [7]. Any significant

lesion should be treated operatively [8]. According to Guehring et al., for defects involving less than 25% of the articular surface closed

reduction is the first choice of treatment; patients with unstable

joints and bone defects >25% could benefit of operative treatment,

with arthroplasty being recommended if the bone defect is >40%

[9,10]. For defects between 25% and 40% a plethora of treatment

modalities can be adopted including the classical or the modified

McLaughlin technique, bone grafts, etc. [11.12]. In our patient, we

opted for a humeral head allograft to obtain an anatomic restoration.

We preferred this procedure to non-anatomic procedures as

subscapularis tendon transfer (i.e. classic McLaughlin) or the lesser

tuberosity transfer (i.e. modified McLaughlin) because, according

to authors, a non-anatomic restoration of the humeral head

sphericity can lead to a decreased internal rotation of the shoulder

and can complicate a foreseeable prosthetic reconstruction [3, 4,

5]. Our patient had borderline indications for hemiarthroplasty.

Considering his relatively young age and global clinical assessment,

we decided to perform an allograft procedure to respect the

patient’s high functional demand of the affected limb. Furthermore,

we agree with authors which alert on the difficulty to manage the

moderate-sized Hill Sachs lesions (i.e. sizing between 40-55%),

even for experienced shoulder surgeons: young and middle-aged

individuals with high functional demand can benefit of a delay in

the hemiarthroplasty surgery by preserving the sphericity of the

humeral head [6]. Concerning the graft type, most literature focus

on cancellous allograft or autograft to treat acute posterior shoulder

dislocation. These grafts are used as a void filler after lifting off the

previous impacted articular surface to better stabilized the lesion

gap and promote bone healing [1]. For defect between 25% and 40%

some authors report reconstruction of the articular surface with

fresh-frozen osteochondral allograft [1, 5, 13, 22, 23]. No specific

guideline has been proposed for the choice of the allograft. Some

authors used a fresh-frozen femoral head allograft. In particular,

authors report good functional outcomes using a femoral head

allograft for treating locked chronic posterior shoulder dislocation

in patients having 25-50% articular surface bony defects [5,13].

The same good results are described in a case report by Patrizio et

al. [22]. The most frequent possible complications recorded with

this procedure are graft resorption, articular surface flattening and

arthritis [5, 13]. Other authors. Proposed the use of a fresh-frozen

talus allograft in case of limited accessibility of humeral head graft.

They described a similar congruency between the radii of curvature

observed with the taller dome and with the humeral head, allowing

for application to broader category of patients [23].

The use of fresh-frozen humeral head allograft has been

described by Martinez et al. in 5 patients affected by GHJ instability

after posterior GH dislocation and in 1 patient with chronic GH

dislocation. All patients had a 40% humeral defect. The study had

a follow-up period of 10 years; 4 patients had satisfying outcomes

while 2 suffered collapsing of the graft [1]. When comparing our

case with the aforementioned paper, we obtained from the bone

bank an accurate sized humerus matching the patient’s one. By

doing so we were able to better fill the gap and restore the precise

curvature of the humeral head of the patient, rather than with the

use of femoral head, achieving an anatomical restoration. By filling

the defect using a humeral head allograft we aimed at preserving

both shoulder stability and function, while maintaining the integrity

of anatomic soft tissue attachments and preserving the remaining

articular surface. Our case report showed how operative treatment

options must be patient-targeted according to each intrinsic factors

(e.g. age, functional demand, comorbidities, etc.), to the type of

injury (e.g. extension of bone defects) and its severity [14, 15]. Our

patient had a high functional demand influencing his work-related

activities and reported consistent pain for up to three months.

Patients with posterior GHJ dislocation suffer a diagnosis delay

and often report aspecific symptoms during healthcare evaluation

[16, 17]. Our patient as well had aspecific symptoms; apart from

significant pain and loss of motion, patients with chronic GHJ

dislocation may show shoulder muscle atrophy and prominent

acromion on the opposite side, while the dislodged humeral head

can be palpated on the back of the shoulder [18]. XR findings can

mislead clinicians as the AP view could show no sign of posterior GHJ

dislocation: axillary-lateral or Y views (hard to obtain if consistent

pain is present), CT scan and/or, as in our case, an MRI can unmask

the dislocation [7, 19]. Diagnosis delay pivots the treatment: in a

case series study it is highlighted how patients promptly treated

for acute dislocation have a better outcome and are easier to treat

[20]. During follow-up, our patient has undergone rehabilitation

therapy; post-operative recovery consists of strengthening exercise

neuromuscular re-education, while educating the patients to avoid

flexion, adduction and internal rotation movements [19, 21]. We

acknowledge the limitations of this paper due to limited follow-up.

Conclusion

Posterior GHJ dislocation greatly benefits early diagnosis. If a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion is associated, there is the need of standardized treatment protocols for management of this condition. An important limit we faced when searching the literature is the paucity of studies with a large number of cases treating GHJ dislocation with a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion: we strongly recommend for future studies to unveil possible benefits and limitations, especially involving the benefits of bone grafts. We want to emphasize the importance of preserving the GHJ anatomy in the young, active patient by delaying prosthetic replacement only once necessary. We want to point out how, even if the graft procedure fails there is still the possibility to proceed with a salvage procedure (i.e. prosthetic replacement), that will be found easier to perform over a preserved humeral head anatomy.

References

- Martinez A A, Calvo A, Domingo J, Cuenca J, Herrera A, et al. (2008) Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head associated with posterior dislocations of the shoulder Injury 39(3): 319-322.

- Antonio A, Navarro E, Iglesias D, Domingo J, Calvo A, et al. (2013) Long-term follow-up of allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head associated with posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Injury 44(4): 488-491.

- Aydin N, Kayaalp ME, Asansu M, Karaismailoglu B (2019) Treatment options for locked posterior shoulder dislocations and clinical outcomes. EFORT Open Rev 4(5): 194-200.

- Kokkalis ZT, Mavrogenis AF, Ballas EG, Papanastasiou J, Papagelopoulos PJ, et al. (2013) Modified mclaughlin technique for neglected locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Orthopedics 36(7): 912-916.

- Diklic ID, Ganic ZD, Blagojevic ZD, Nho SJ, Romeo AA, et al. (2010) “Treatment of locked chronic posterior dislocation of the shoulder by reconstruction of the defect in the humeral head with an allograft. J Bone Jt Surg 92(1): 71-76.

- Murphy LE, Tucker A, Charlwood AP (2018) Fresh frozen femoral head osteochondral allograft reconstruction of the humeral head reverse hill sachs lesion. J Orthop 15(3): 772-775.

- Shah N, Tung GA (2009) Imaging signs of posterior glenohumeral instability. American Journal of Roentgenology 192(3): 730-735.

- Bock P, Kluger R, Hintermann B (2007) Anatomical reconstruction for Reverse Hill-Sachs lesions after posterior locked shoulder dislocation fracture: A case series of six patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 127: 543-547.

- Guehring M, Lambert S, Stoeckle U, Ziegler P (2017) Posterior shoulder dislocation with associated reverse Hill-Sachs lesion: Treatment options and functional outcome after a 5-year follow up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18(1): 1-7.

- Flatow EL, Miniaci A, Evans PJ, Simonian PT, Warren RF, et al. (1998) Instability of the shoulder: Complex problems and failed repairs. Part II. Failed repairs. J Bone Jt Surg Ser A 47: 113-125.

- Perrenoud A, Imhoff AB (1996) Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 54(3): 165-168.

- Mastrokalos DS, Panagopoulos GN, Galanopoulos IP, Papagelopoulos PJ (2017) Posterior shoulder dislocation with a reverse Hill–Sachs lesion treated with frozen femoral head bone allograft combined with osteochondral autograft transfer. Knee Surgery Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 25(10): 3285-3288.

- Gerber C, Lambert SM (1996) Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head for the treatment of chronic locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Jt Surg Ser A 78(3): 376-382.

- Burkhead WZ, Rockwood CA (1992) Treatment of instability of the shoulder with an exercise program. J Bone Jt. Surg Ser A 74(6): 890-896.

- Fronek J, Warren RF, Bowen M (1989) Posterior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint. JBone Jt Surg Ser A 71(2): 205-216.

- Sahajpal DT, Zuckerman JD (2008) Chronic glenohumeral dislocation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 16(7): 385-398.

- Rowe CR, Zarins B (1982) Chronic unreduced dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone Jt Surg Ser A 64(4): 494-505.

- Imhoff AB, Savoie FH (2017) Shoulder instability across the life span. Shoulder Instab. Across Life Span 1-307.

- Alepuz ES, Pérez-Barquero JA, Jorge NJ, García FL, Baixauli VC, et al. (2017) Treatment of The Posterior Unstable Shoulder. Open Orthop J 11(1): 826-847.

- PavoneV, Vincenzo Fabrizio Caruso, Emanuele Chisari, Sebastiano Mangano, Gianluca Testa, et al. (2018) Surgical and rehabilitative treatment of misdiagnosed posterior dislocation of the shoulder: Case series. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 3(2): pp. 30.

- Eckenrode BJ, Logerstedt DS, Sennett BJ (2009) Rehabilitation and functional outcomes in collegiate wrestlers following a posterior shoulder stabilization procedure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 39(7): 550-559.

- Patrizio L, Sabetta E (2011) Acute posterior shoulder dislocation with reverse HilleSachs lesion of the epiphyseal humeral head. ISRN Surg 2011: 851051.

- Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Ghodadra N, Solomon DJ (2010) Postsurgical glenohumeral anchor arthropathy treated with a fresh distal tibia allograft to the glenoid and a fresh allograft to the humeral head. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 19(6): e6-e11.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...