Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-6003

Research Article(ISSN: 2638-6003)

Locked Bridge Plating is a Suitable Option for Forearm Fractures Secondary to Civilian Low Velocity Gunshot Injuries Volume 4 - Issue 5

Vaidya Rahul*, Washington Austen and Ryan Bray

- Detroit Medical Center, Heart Hospital, USA

Received: January 6, 2021; Published:January 18, 2021

Corresponding author:Rahul Vaidya, Heart Hospital 5th Floor, USA

DOI: 10.32474/OSMOAJ.2021.04.000200

<

Abstract

Introduction: The purpose of this retrospective study is to compare the outcomes of low velocity gunshot fractures of the forearm treated with minimal debridement and locked bridge plating to patients treated with formal debridement and conventional plating.

Materials and Methods: A 10 year IRB approved retrospective review of our national trauma database was conducted. Initial treatment consisted of wound care and sterile dressing. Forearm radiographs were acquired to determine bony involvement. All patients received intravenous antibiotics upon presentation to the emergency department and for a minimum of forty-eight hours after admission or operative intervention. Patients were placed into two categories of operative or nonoperative treatment. Those placed into operative treatment were further divided into the subcategories of formal debridement and plating or minimal debridement and plating.

Results: 94 patients were included in the study. 29 were treated nonoperatively and 65 were treated operatively. Of those 65, 30 underwent minimal debridement and bridge plating and 35 were treated with formal debridement and bridge plating. All patient radiographs displayed fracture healing at latest follow-up with no evidence of infection or osteomyelitis. Nerve injuries were found among 15 patients and vascular injuries were present in 7.

Conclusions: Both methods of irrigation and debridement resulted in reliable osseous union with no instances of osteomyelitis. These results suggest that immediate locked bridge plating with minimal debridement is a suitable option for the treatment of forearm fractures following low velocity gunshot injuries.

Keywords: Irrigation; Debridement; Forearm; Gunshot; Fracture; Minimal

Introduction

There are 300,000 injuries and 30,000 hospitalizations from gunshot wounds annually in the United States [1-3] primarily from low-velocity handguns. These weapons produce less soft-tissue injury than high-velocity rifles or shotguns attributed to lower mass, velocity and energy transfer of the projectiles to surrounding tissues [4, 5]. Gunshot wounds of the forearm have been reported in several small series in the literature; however, no treatment guidelines backed by adequate scientific evidence exist. Prior studies with limited numbers have recommended debridement irrigation, antibiotics and compression plating for displaced fractures of one or both bones, and immobilization for undisplaced simple fractures of single bones. We feel that aggressive debridement and conventional compression plating may not be practical for these injuries which often have boney comminution but minimal soft tissue injury. A potential alternative is limited debridement and bridge plating. The purpose of this study is to compare the outcomes of low velocity gunshot fractures of the forearm treated with minimal debridement and locked bridge plating to patients treated with formal debridement and conventional plating.

Materials and Methods

An IRB approved 10-year retrospective review of our hospital

trauma database revealed one-hundred and one patient admitted

to the hospital with forearm fractures following gunshot wound

(2000-2010). Seven patients were excluded from the study as

their injuries were the result of a high-velocity firearm, leaving

ninety-four patients treated for gunshot wounds of the forearm

with hospitalization. Patients who were discharged from the

emergency room with gunshot wounds with or without fractures

and patients who left the hospital against medical advice prior to

treatment were not captured in this database. There were eightythree

males and eleven females. The average age was 27.7 years

with a range of 16-52 years. The average duration of follow-up

of all patients was 27.3 months with a range of 9 to 105 months.

Treatment was initiated with wound care by applying a sterile

dressing in the emergency department. Forearm radiographs were

acquired to determine bony involvement. Clinical suspicion of limb

ischemia by physical exam was an indication for angiography. All

patients received intravenous antibiotics upon presentation to the

emergency department and for a minimum of forty-eight hours after

admission or operative intervention. The initial antibiotic selected

was cefazolin with or without gentamicin, and some patients with

concomitant thoracic or abdominal injuries received additional

antibiotics for greater time periods. Patients with non-displaced or

minimally displaced fractures were treated non-operatively with

local wound care, antibiotics, and casting. Displaced fractures were

divided into 2 groups.

During the first 5 years 35 patients underwent aggressive

debridement and irrigation of wounds, fracture stabilization using

compression plating techniques when feasible and bridge plating

when there was bone loss. Antibiotic cement spacers were placed

where there was bone loss followed by delayed grafting using

iliac crest bone. Eight were stabilized with initial external fixation

followed by plating and 27 had immediate plate fixation. The

second 5 years included 30 patients treated with open reduction

and internal fixation (ORIF) with a bridge plating technique, limited

irrigation and debridement of entry and exit wounds locally at

the level of skin and subcutaneous tissue without debridement of

bone. This was intended to minimize soft tissue stripping around

the fracture site. Bullet fragments were not disturbed unless they

were superficial and easily removed without further damaging the

surrounding soft tissues. Entrance and exit wounds were not closed

primarily. Patients with non-displaced or minimally displaced

fractures (29) were treated non-operatively with local wound care,

antibiotics and casting. These were often admitted for concomitant

injuries and thus were picked up in our database. We reviewed

all radiographic images obtained at presentation and during

treatment. Fractures were classified as radius, ulna or both (Figure

1). The fracture location was noted whether they were proximal,

midshaft or distal and if they were non-displaced or minimally

displaced versus comminuted and displaced. Radiographic data

were used to determine the status of fracture healing or hardware

failure. Patients were examined in the clinic (Figure 2) to assess for

fracture healing, infection, presence of deformity, sensory or motor

deficits, and range of motion. Range of motion was classified as good

(<10 degrees flexion extension loss and <25 degree pronation/

supination loss), satisfactory (<30 degree flexion extension loss

and <50 degree pronation/supination loss) or poor (>30 degree

flexion extension loss or >50 degree pronation/supination loss)

Results

Operative Treatment

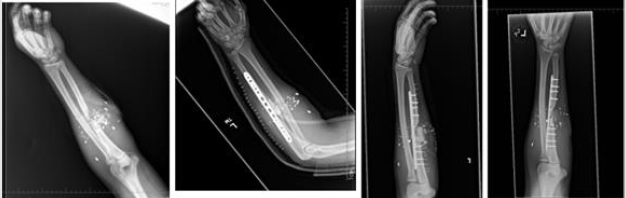

Sixty-five patients were treated operatively. Thirty patients underwent bridge plating and minimal debridement of the gunshot wounds without excision of only frankly necrotic tissue and minimal to no bone debridement and no bone grafting (Figure 3). Thirtyfive patients were treated with formal irrigation and debridement of the wounds and stabilization (Figure 4). Of the thirty patients with bridge plating and limited debridement twenty-nine patients displayed fracture healing at their latest follow up and one patient required revision surgery for delayed union. There were no signs of infection or osteomyelitis at final follow up. Of the thirty-five patients treated with more aggressive irrigation and debridement with fracture stabilization, seven patients were determined to have more extensive soft tissue injury requiring multiple surgeries and more aggressive debridement and eventual soft tissue coverage. Five of these seven required early bone grafting after original damage control surgery and prior to soft tissue reconstruction. All patients displayed radiologic evidence of healing at their latest follow up with no patient showing signs of infection or osteomyelitis.

Non-Operative Treatment

Twenty nine patients were treated non-operatively with local wound care and casting for forearm fractures. All patients had a single bone non-displaced or minimally displaced fracture. All patients displayed radiographic evidence of fracture healing at their latest follow up with no patient showing signs of infection or osteomyelitis. Range of motion in this subset was determined to be satisfactory or good at final follow up.

Nerve Injuries

There were fifteen patients with an associated nerve injury. The ulnar and median nerve were the most common nerves injured (six patients each) followed by the radial nerve in four patients and the palmar cutaneous nerve and anterior interosseous nerves in one patient each. Three patients had multiple nerve injuries. In seven patients the nerve injury resolved completely and in five patients a partial nerve deficit was observed. Three patients showed no recovery with one patient displaying a classical ulnar claw hand deformity.

Vascular Injury

Seven patients presented with signs of associated vascular injury of the forearm. There were four radial artery injuries and four ulnar artery injuries. One patient had both arteries injured and repaired. All patients had a viable limb on follow up. Three patients had nerve injury associated with vascular injury. One patient developed a compartment syndrome requiring fasciotomy.

Discussion

Early stabilization of forearm fractures is important after a

gunshot injury and the management of the open wound and soft

tissue injury is always an important consideration for surgical

planning. In this study, we showed that minimal irrigation and

debridement of the entrance and exit wounds is adequate for

low velocity gunshot injuries to the forearm with minor visible

soft tissue injury, and that bridge plating with minimal surgical

dissection through the zone of injury is sufficient to achieve reliable

union of these fractures. Dicpinigaitis, et al. showed that most

non-displaced fractures of the radius or ulna can be effectively

managed with casting al in their review of the literature addressing

gunshot wounds to the extremities, but displaced fractures should

be treated operatively with compression plating [4]. reported

superior results in patients treated with delayed primary ORIF

with displaced forearm fractures secondary to gunshot wounds

[12]. In the same study, no patients treated by delayed ORIF went

on to melanin or delayed union, but all patients did have decreased

range-of-motion, particularly pronation and supination. Rodrigues,

et al. recommended a treatment protocol involving early wound

care and provisional stabilization followed by definitive treatment

with internal fixation within one week [18-20]. In our review, thirty

five patients were successfully treated with a more extensive soft

tissue debridement with fracture stabilization, and thirty patients

with comminuted and displaced fractures were effectively treated

with local wound care followed by internal fixation with bridge

plating.

Several studies have also examined the effectiveness of nonsurgical

treatment in non-displaced or minimally displaced

forearm fractures resulting from low-velocity firearms. Elstrom,

et al. reported on fourteen patients that were treated with casting

[12]. In eight non-displaced single bone fractures, seven had good

outcomes. In six displaced fractures, closed reduction and casting

lead to poor outcomes in four patients. Lenihan ,et al. reported

on thirty-seven patients with civilian gunshot wounds to the

radius and ulna [13]. Twenty-three patients with non-displaced

fractures were treated by closed means with twenty-one showing

good outcomes. However, in the fourteen patients with displaced

fractures, the outcomes of the eight patients who had closed

reduction were worse than the six patients treated surgically.

Dickson, et al. prospectively evaluated patients with non-displaced

fractures treated as outpatients with closed reduction and casting

[3]. Only one patient in their study went on to delayed union

[3]. also reported excellent results in patients of non-displaced

fractures treated with closed reduction in a long arm cast, with

seven of eight patients showing evidence of fracture healing and

good functional outcome. The same study reported that four out of

six patients with comminuted and displaced fractures treated with

casting went on to malunion or delayed union resulting in a poor

functional outcome. The authors concluded that closed reduction

has satisfactory results in non-displaced fractures while displaced

fractures require internal fixation to achieve superior outcomes. In

our retrospective review we found similar results and agree that

patients with minimally displaced or non-displaced extra-articular

fractures can be adequately treated with closed reduction and

casting without surgical debridement. We add to these findings

that extensive surgical debridement can also be withheld with

low risk of infection or nonunion after bridge plating for fracture

stabilization.

Past studies have shown that bullets are not sterilized during

discharge of the weapon and may act as a vector introducing

pathogenic bacteria into the wound4. Controversy exists, however,

as to the necessity of administering prophylactic antibiotics to this

patient population. Patzakis, et al. demonstrated an infection rate

of 13.9% in patients with open fractures resulting from gunshot

wounds not treated with antibiotics and an infection rate of 2.3%

in patients treated with cephalothin [7]. The study also showed

no statistically significant difference in infection rate between

the control group (13.9%) and a group treated with penicillin

and streptomycin (9.7%) [7]. Conversely investigated the efficacy

of antibiotics in a similar patient population and showed no

significant difference in infection rate between the control group

and the experimental group treated with at least twenty-four hours of intravenous cefazolin [2]. concluded in a prospective study

that short-term intravenous antibiotics did not decrease the risk

of infection [9]. recommended the use of prophylactic antibiotics

in high-velocity and intra-articular injuries but did not support

the use of prophylactic antibiotics for low-velocity injuries [10].

Howland and Ritchey in a retrospective analysis concluded that

prophylactic antibiotics were unnecessary in the treatment of lowvelocity

gunshot fractures [11-20]. In our study, all patients were

treated with intravenous first generation cephalosporin antibiotics,

and in some cases additional antibiotics to treat other concurrent

injuries. As no patient in our review developed osteomyelitis even

with a large subset undergoing limited debridement, we support

the use of a first-generation cephalosporin for 48 hours in patients

reporting with open forearm fractures secondary to low-velocity

gunshot wounds.

We recognize the following limitations of our study. First, it is

retrospective in nature and carries all the associated risks of bias. It

is additionally possibly biased towards more severe injuries since

all included patients were admitted for at least 48 hours. Patients

with minor gunshot forearm injuries and treated as outpatients

had variable antibiotic regimens or no antibiotics and were not

captured in this database. Thirdly, the patient population of this

study is small, although it is larger than previously published

studies. Furthermore, we had difficulty in contacting patients in our

study for longer term follow up.

Conclusion

Forearm fractures caused by low velocity gunshot wounds in a civilian setting are often comminuted single bone injuries with minor soft tissue injury. Both the aggressive and limited debridement regimens resulted in reliable osseous union and no instances of osteomyelitis. These results suggest that immediate locked bridge plating with minimal debridement is a suitable option for the treatment of forearm fractures following low velocity gunshot injuries.

Acknowledgements

Authors have no acknowledgements to report.

Sources of Funding

Authors report no sources of funding were utilized.

References

- Cook A, Osler T, Hosmer D, Glance L, Rogers F, et al. (2017) Gunshot wounds resulting in hospitalization in the United States 2004-2013. Injury 48(3): 621-627.

- Dickey RL, Barnes BC, Kearns RJ, Tullos HS (1989) Efficacy of Antibiotics in low-velocity gunshot fractures. J Orthop Trauma 3(1): 6-10.

- Dickson K, Watson TS, Haddad C, Jenne J, Harris M, et al. (2001) Outpatient management of low-velocity gunshot-induced fractures. Orthopedics 24(10): 951-954.

- Dicpinigaitis PA, Koval KJ, Tejwani NC, Kenneth A Egol, et al. (2006) Gunshot wounds to the extremities. Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases 64(3&4):139-155.

- Bartlett CS, Helfet DL, Hausman MR, Strauss E (2000) Ballistics and gunshot wounds: effects on musculoskeletal tissues. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 8(1): 21-36.

- Woloszyn JT, Uitvlugt GM, Castle ME (1988) Management of civilian gunshot fractures of the extremities. Clin Orthop Relat Res (226): 247-251.

- Patzakis MJ, Harvey JP, Ivler D (1974) The role of antibiotics in the management of open fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 56(3): 532-541.

- Knapp TP, Patzakis MJ, Lee J, P R Seipel, K Abdollahi, et al. (1996) Comparison of intravenous and oral antibiotic therapy in treatment of fractures caused by low-velocity gunshots. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 78(8): 1167-1171.

- Geissler WB, Teasedall RD, Tomasin JD, Hughes JL (1990) Management of low velocity gunshot-induced fractures. J Orthop Trauma 4(1): 39-41.

- Simpson BM, Wilson RH, Grant RE (2003) Antibiotic therapy in gunshot wound injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res (408): 882-885.

- Howland WS Jr, Ritchey SJ (1971) Gunshot fractures in civilian practice. An evaluation of the results of limited surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 53(1): 47-55.

- Elstrom JA, Pankovich AM, Egwele R (1978) Extra-artciular low-velocity gunshot fractures of the radius and ulna. J Bone Joint Surg Am 60(3): 335-341.

- Lenihan MR, Brien WW, Gellman H, Itamura J, Kuschner SH, et al. (1992) Fractures of the forearm resulting from low-velocity gunshot wounds. J Orthop Trauma 6(1): 32-35.

- Chapman MW, Mahoney M (1979) the role of early internal fixation in the management of open fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res (138):120-131.

- Duncan R, Geissler W, Freeland Ad, Savoie FH (1992) Immediate internal fixation of open fractures of the diaphysis of the forearm. J Orthop Trauma 6(1): 25-31.

- Jones JA (1991) Immediate internal fixation of high-energy open forearm fractures. J Orthop Trauma 5(3): 272-279.

- Moed BR, Kellam JF, Foster RJ, Tile M, Hansen Jr ST, et al. (1986) Immediate internal fixation of open fractures of the diaphysis of the forearm. J Bone Joint Surg Am 68(7): 1008-1017.

- Rodrigues RL, Sammer DM, Chung KC (2006) Treatment of complex below-the-elbow gunshot wounds. Ann Plast Surg 56(2): 122-127.

- Moed BR, Fakhouri AJ (1991) Compartment syndrome after low-velocity gunshot wounds to the forearm. J Orthop Trauma 5(2): 134-137.

- Bowyer GW, Rossiter ND (1997) Management of gunshot wounds of the limbs. J Bone Joint Surg Am 79(6): 1031-1036.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...