Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-6003

Research Article(ISSN: 2638-6003)

Are we Ready for Hip Fracture Geriatric Patients? Study with 224 Patients of the Fourth Age Volume 3 - Issue 2

Calvin L Cole1,2*, Kostantinos Vasalos1,2, Gregg Nicandri1,2, Cameron Apt1,2, Emmalyn Osterling1,2, Zachary Ferrara1,2, Michael D Maloney1,2, Edward M Schwarz1,2 and Katherine Rizzone1,2

- 1Center for Musculoskeletal Research, University of Rochester Medical Center, USA

- 2Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, University of Rochester Medical Center, USA

Received: November 28, 2019 Published: December 03, 2019

Corresponding author: Luiz Eduardo Imbelloni MD, PhD, Rua Coroados, 162/45-B, Vila Anastácio, 05092-020- São Paulo, SP-Brazil

DOI: 10.32474/OSMOAJ.2019.03.000159

Abstract

Background: The demographic criterion by age group, that of the old-old, 80 years old or older, so-called the Fourth Age. In Brazil, in 2018 there are four million people in the fourth age. As life expectancy increases, the number of geriatric patients coming for surgery and anesthesia will make up an increasing portion of our practice. The primary aim of orthopedic treatment for these elderly patients can be a return to independent life, that is, independent walking, dressing, toilet functions and eating. The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the implementation of project acceleration of postoperative recovery (fast track surgery), in the Fourth Age patients undergoing hip fracture surgery under spinal anesthesia and peripheral block for postoperative analgesia. The second objective was to assess the need for ICU, length of stay, abbreviation of preoperative and postoperative fasting, oral food reintroduction and mortality in the first month after surgery.

Methods: We studied a longitudinal prospective study in patients over the age of 80 years (Four Age) undergoing corrective hip fracture, of both genders from 1st July 2012 to 30 December 2018, at a hospital covered by the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS). Information on the preoperative condition of these patients, abbreviation for fasting, hunger and thirst assessment, mode of anesthesia, drugs used, intra-operatively measured variables (e.g. hemodynamics, blood loss) and immediate post-operative variables measured in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), quality of lumbar plexus block analgesia, presence of delirium in the first day of postoperative was obtained from the study protocol and death in the first postoperative month.

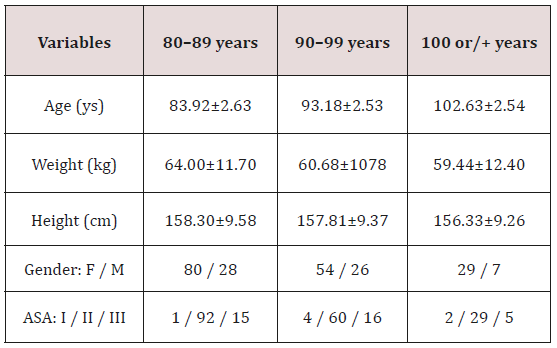

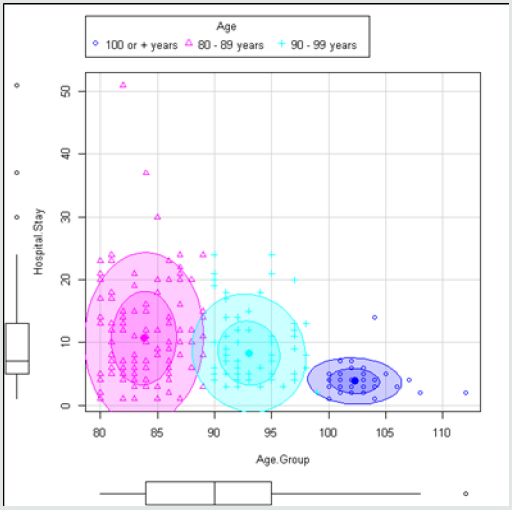

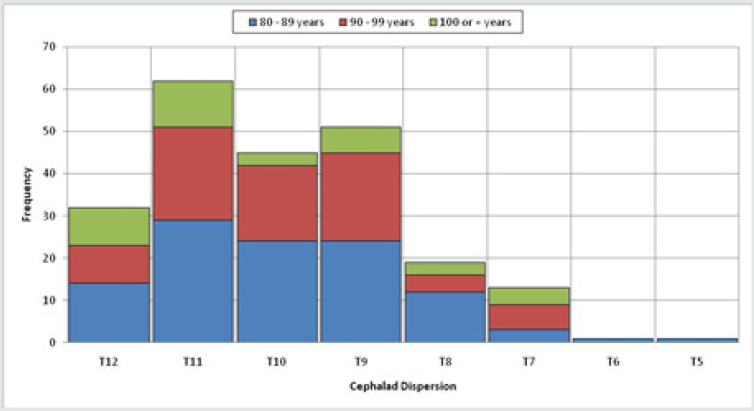

Results: During the period of study (six years) 224 Fourth Age patients underwent surgery for a fracture of the hip, of whom 163 (73%) were women and 61 (27%) were men (Table 1). Prior to injury, all of the patients were living at home. The average hospital stay in all 224 patients was 9.5±6.9 days, and there is an association between age and length of stay. The mean fasting time was 2:56±0:38 hours (Table 2), and no significant difference between the three groups. All patients were submitted to spinal anesthesia. The dose ranged from 6 to 15mg, with a mean of 9.54± 1:64 mg isobaric bupivacaine. The cephalad dispersion varied between T12 and T5, in all patients, and the mode was the same T11 regardless of age group of patients. The duration of the spinal block was 2:44±0:37 hours, the time for the use of dextrinomaltose in PACU was 1:43±0:46 hours, the time in the PACU was 2:03±0:43 hours and the time to reintroduce normal meals were 6:09±1:02 hours. Arterial hypotension occurred in 6 patients and delirium in 13 patients. Of the 224 patients, only 4 (1.8%) were referred to the ICU due to surgical problems. There were no deaths directly related to anesthesia or surgery.

Conclusion: The implementation of the ACERTO Project in Fourth Age patients of the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS), showed that there was a marked improvement in length of stay, patient satisfaction, decreased use of bladder tube and drains, and referral to ICU, with early discharge to residence.

Keywords: Surgery; Orthopedic; Spinal anesthesia; Fasting; Perioperative care; Fast-track surgery

Introduction

Recognition of a person as being elderly may be changing from decade to decade. Sixty year old males were elderly in the 1960s; however, this is very active age physically and mentally in twenty first century. Although there is no clear definition, people more than 65 years of age are considered to be elderly people. There are two ways to classify aging: the demographic criterion by age group, i.e. the old-young age ranging from 60 to 79 years old, the so-called “Third Age”; and that of the old-old, 80 years old or older, the “Fourth Age.” The other parameter is individual. Distinguishes people based on genetic inheritance, personality and way of life. Thus, there are relatively young individuals with dependencies more common to older people and people from 80, 90, up to 100 years old who remain healthy and autonomous. In 2017, Brazil’s elderly population exceeded 30 million, and the fastest growing segment is 80 years or older. Studies show that in the last 30 years the quality of life of elderly Brazilians has not only improved, but healthy longevity has increased [1]. A combined orthopedic geriatric rehabilitation ward was created in the United Kingdom in the early 1950s [2]. Dr. Devas, an English orthopedic surgeon, used a term ‘Geriatric Orthopedics’ in 1974 [3]. In 2006, the authors point out that, from a demographic point of view, health problems become more severe after the Fourth Age, the most well-known being :

a) Loss of cognitive potential and ability to learn

b) Increased symptoms of chronic stress

c) High prevalence of senile dementia, becoming more

pronounced from the age of 90

d) High level of frailty due to the combination of multiple motor,

chronic and degenerative diseases [4].

Geriatric people are not just old adults. Adjustments in health requirements are required for this group of patients in both medical research and health policy [5]. Osteoporosis, which is frequently encountered in the elderly, should be carefully considered and it is now a treatable condition. After the fall there is a tendency of the elderly to suffer several types of fractures the most common being femur fractures. The primary aim of orthopedic treatment for these elderly patients must be the return of function, yet in certain patients who have severe comorbidities; the aim of treatment can be a return to independent life, that is, independent walking, dressing, toilet functions and eating. This type of surgery is a major public health problem, every year; the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) has expenses femur fracture treatments in four age patients. Bayesian descriptive analyses of spatial and time series were performed on data obtained from the Hospital of SUS, using Poisson regression for femoral fractures in individuals 60 years of age or older from 2008 to 2012. There were more than 181,000 femoral fractures during this period, predominantly in women, without important spatial correlations or temporal differences [6]. The social and economic cost is further increased by fact that after a period of hospitalization the elderly patient shows a decrease in recovery, faces high rates mortality, requiring intensive medical care and long periods of rehabilitation. In the present study, we attempted to identify the type of problems that might have occurred perioperatively in the Four Age hip surgical patients. We analyzed the course of anesthesia in detail, as well as immediate and longerterm outcome in octogenarians, nonagenarians and centenarians undergoing orthopedic surgery in our hospital for six years. The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the implementation of project acceleration of postoperative recovery (fast track surgery), in the Fourth Age patients undergoing hip fracture surgery under spinal anesthesia and peripheral block for postoperative analgesia. The second objective was to assess the need for ICU, length of stay, abbreviation of preoperative and postoperative fasting, oral food reintroduction and mortality in the first month after surgery.

Methods

We studied a longitudinal prospective study in a patient over the age of 80 years (Fourth Age) undergoing corrective hip fracture, ASA physical status I-III, of both genders from 1st July 2012 to 30 December 2018, at a hospital covered by the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS). The protocol was registered in Brazil Platform (CAAE: 09061312.1.0000.5179). The Ethics Research Committee approved the study protocol and all patients were informed and agreed to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were: normal blood volume, no pre‑existing neurological disease, no coagulation disorders, without infection at the puncture site, which did not present agitation, mental confusion and/or delirium, which did not make use of bladder indwelling catheters, with hemoglobin level >10g% and that was not in the ICU. All patients over 80 years with femur fractures were anesthetized by the same anesthesiologist, accompanied by a resident in anesthesia. All patients received 200mL of 12.5% dextrin maltose 2 to 4 hours before being referred to the operating room and noted the time of fasting and the presence of thirst and hunger. Information on the pre-operative condition of these patients, mode of anesthesia, drugs used, intraoperatively measured variables (e.g. hemodynamics, blood loss) and immediate post-operative variables measured in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU), and first day of postoperative was obtained from the study protocol. Premedication was not used. Monitoring consisted to EKG, of noninvasive blood pressure, heart rate, and pulse oximetry. After venous cannulation with 18G catheter in the hand or forearm, infusion of Ringer’s lactate in parallel with 6% hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 in 0.9% sodium chloride injection was started. At the beginning of monitoring was administered cefazolin 2g and dexamethasone 10mg intravenously. After sedation with intravenous dextroketamine (0.1 mg/kg) and midazolam (0.5-1 mg), skin cleansing with chlorhexedine 0.5% alcoholic and expected to dry, spinal puncture was performed with the patient in sitting position, through the median interspaces L2-L3 or L3-L4, using a 26G or 27G Quincke needle. After observing CSF confirming the correct position of the needle, 6 to15 mg of 0.5% isobaric bupivacaine were administered at a rate of 1mL/15s. Patients were immediately placed in supine position for surgery.

The sensorial blockade and motor blockade were evaluated at 10min after injection. Cardiorespiratory parameters were measured every 5 minutes. Hypotension (a reduction in SBP > 30% when compared to the pressure in the regular ward) was treated with ethylephrine (2mg IV), while bradycardia (HR<45 bpm) was treated with atropine (0.50mg IV). At the end of surgery, patients received tenoxicam 40 mg and dypirone 40 mg/kg in 50 mL of Ringer’s lactate. The postoperative analgesia was performed through the anterior lumbar plexus block (inguinal) or posterior (psoas compartment) with a neuroestimulator. In patients who would be operated in the supine position, anterior lumbar plexus block was performed before the beginning of spinal anesthesia in PACU with 20mL of 2% lidocaine+epinephrine and 20mL of 0.5% bupivacaine. In patients who were operated in lateral decubitus (left or right) posterior lumbar plexus block (psoas compartment) was performed at the end of surgery. Obtained the desired contraction, were injected 40mL bupivacaine 0.25%. In PACU after termination of motor block, patients received 200 mL of 12.5% dextrinomaltose. If in 30 minutes nausea and vomiting did not occur, they would be sent to the infirmary. Data relating to surgical time, recovery time of motor block, time to administration dextrinomaltose, length of stay in the PACU, need for catheterization, pain, treatments administered and noted the time of reintroduction of oral feeding were recorded by an observer. Delirium was used to refer to drowsiness, disorientation, and hallucination. Patients were followed until the second day after surgery to assess the conditions of discharge. Patients were followed in relation to morbidity and mortality after hospital discharge during the first month by phone.

Statistical Analysis

The tests used for data analysis were non‑parametric Kruskal- Wallis test in an extension of Wilconxon-Mann Whitney test. To compare the frequency distributions of qualitative variables, Perarson’s chi-square test was use. The p-values less than 0.05 (p<0.05), a statistically significant association between the variables was considered.

Results

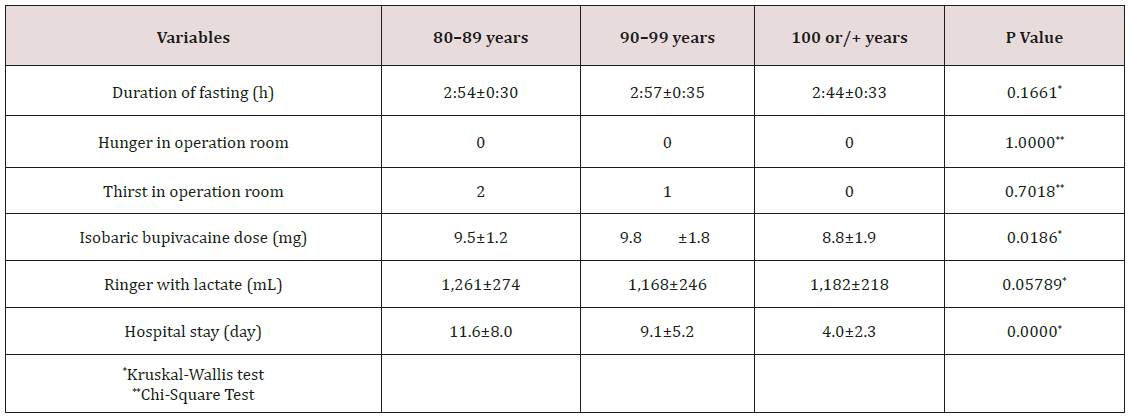

During the period of study (six years) 224 Fourth Age patients underwent surgery for a fracture of the hip, of whom 163 (73%) were women and 61 (27%) were men. Patient data are shown in (Table I). One hundred and eight patients were between 80 and 89 years old, eighty patients were between 90 and 99 years old and thirty six had more than 100 years old, being the oldest with 112 years old. The major pre-existing illnesses in the 224 patients in Four Age were as a result of arteriosclerotic, cardiac diseases and diabetes. Prior to injury, all of the patients were living at home. Seven patients (3%) had physical status ASA I, 181 patients (81%) ASA II and 36 patients (16%) ASA III. Of the 224 patients, only 4 (1.8%) were referred to the ICU due to surgical problems. The average hospital stay in all 224 patients was 9.5±6.9 days (Table II). There is an association between age and length of stay, as shown by the Kruskal-Wallis test with a p-value close to zero. The correlation is approximately -0.3590, which indicates that the length of stay decreases with increasing age (Figure 1). The mean fasting time was 2:56±0:38 hours (Table 2), and no significant difference between the three groups. This reflected that no patient complained of hunger and only tree patients reported thirst. This reflected in a high degree of satisfaction in all patients. All patients were submitted to spinal anesthesia with 0.5% isobaric bupivacaine and there was no need of general anesthesia. The dose ranged from 6 to 15 mg, with a mean of 9.54±1:64 mg isobaric bupivacaine in all patients. Kruskal-Wallis test indicates no association between age and dose (Table 2). The cephalad dispersion varied between T12 and T5, in all patients, and the mode was the same T11 regardless of age group of patients (Figure 2). Two hundred and fifteen patients had complete motor blockade, and nine patients motor block grade 2. All patients received 500 mL of 6% hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 in 0.9% sodium chloride and Ringer with Lactate (1,215±258mL), and no significant difference between the three groups (Table 2). Nineteen patients (8.4%) received blood transfusion during surgery no significant difference (Chi Square, p=0.9431). Arterial hypotension occurred in six patients, and all hypotension were easily treated with only one dose of ethylephrine. Bradycardia did not occur in any patients.

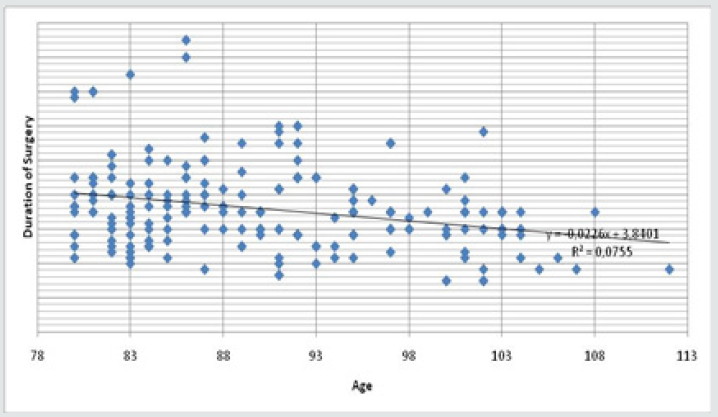

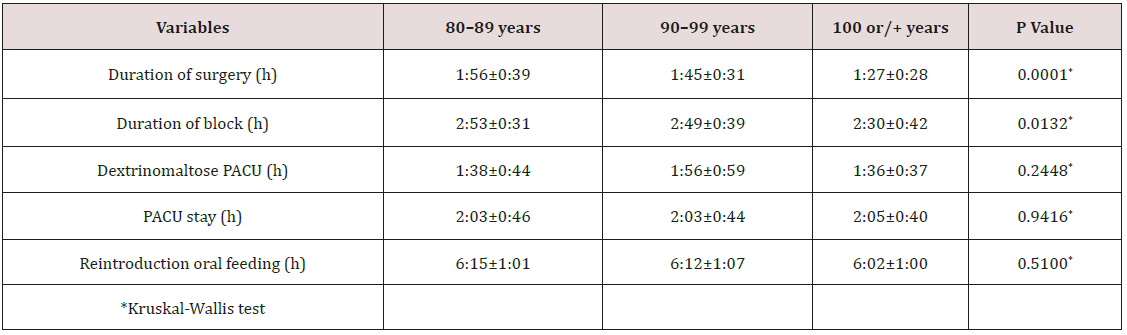

Table 3 shows the duration of the surgery, the duration of the spinal block, the time for the use of dextrinomaltose in the PACU, the time in the PACU and the time to reintroduce normal meals. There was only significant difference in surgery duration being smaller in patients over 100 years. There was a correlation between increasing age and decreasing surgery time by the Kruskal-Wallis test with a significant p value. The correlation has value r = -0.2748 (Figure 3). No patient required a urinary catheter or surgical drain. Post-operative delirium was noted in thirteen patients. No nausea or vomiting occurred in all patients. Four patients were transferred to the ICU for surgical problems. All 220 patients after the implantation of the project were ready for discharge in the first post-operative day. Regional anesthetic techniques were utilized in all patients for post-operative analgesia, and intravenous tenoxican and dypirone. One hundred and thirty patients received lumbar plexus block (inguinal) before surgery in the PACU and 94 received lumbar plexus block (psoas compartment and inguinal) after surgery. The mean duration of analgesia was 21:9±3:43 hours, ranging from 15 to 33 hours postoperatively. All patients survived the surgery and were able to be discharged by the second postoperative day, except the four patients referred for ICU. Twelve patients died at home during the first postoperative month.

Table 2: Duration of fasting, hunger and thirst in OR, ringer with lactate, isobaric doses and hospital stay.

Table 3: Duration of surgery, blocking duration, time to feeding dextrin maltose in PACU, duration of stay in the PACU and time of oral food reintroduction on the ward (m±SD).

Discussion

A preoperative screening visit by an anesthesiologist prior to surgery is of prime importance. It is recommended that screening of an elderly patient be performed prior to the day of surgery. All patients were visited by the same anesthesiologist the day before surgery and were only operated after being included in the study criteria. Our prospective analysis shows that the Fourth Age patients tolerated anesthesia and surgery quite well and can fully participate in projects accelerated postoperative recovery. There were no deaths directly related to anesthesia or surgery or underlying diseases in the first two days after surgery. Of the 224 patients, only 4 (1.7%) were referred to ICU for surgical problems and 12 (5.3%) died in the first month after surgery. In people aged 80 years or older, the incidence of fracture is strongly associated with increasing frailty and female gender, while mortality following fracture is generally greater in men and is more strongly associated with age than frailty status (7). Femur fractures are most frequent and more common in women, and in the present study with Fourth Age patients 73% of them were female and only 27% were men.

The main goals of treatment are to stabilize the hip, decrease pain and restore the level of pre fracture function. Surgery is the preferred treatment for hip fracture because it provides stable fixation, facilitating full weight bearing and decreasing the risk of complications. Surgery is also associated with a shorter stay in the hospital and improved rehabilitation and recovery (8). Surgical stabilization should be performed as soon as possible ideally, within 48 hours (9). In recent systematic review and metaanalysis concluded that early hip surgery within 48 hours was associated with lower mortality risk and fewer perioperative complications (10). In the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) performing surgery within 48 hours is very difficult, due to the scarcity of surgical material. However, with the implementation of the fasttrack project, there was an average decrease from 24 days to 11 days in length of hospital stay (11). In this study with patients of the Fourth Age the average length of stay was 10 days. All 220 patients survived the surgery and were able to be discharged by the second postoperative day, except the four patients referred for ICU. In recent systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that only a few observational studies with a small number of patients comparing nonoperative management with operative management have been published (12). A significantly higher 30-day and 1-year mortality was revealed in nonoperatively treated hip fracture patients above 65 years compared to operatively treated patients. Comorbidity did not seem to purely drive this decision-making. On date were found examining health-related quality of life, degree of frailty, and costs. In this hospital all patients underwent surgery and were unable to make comparisons with nonoperated group.

The elderly represents the fastest-growing population in the world. According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the country closed 2018 with about four million people in the fourth age, 1.97% of the population of just over 208 million (13). This age group of Brazilians is expected to jump to 8.36% by 2060, approximately 19 million of the estimated 228 million inhabitants (13). Advanced age traditionally has been considered a risk for surgery. Aging is associated with a decrease in functional reserves of organ systems and an increase in the presence of comorbid conditions. It is now known that it is comorbidity, rather than age, that contributes significantly to perioperative morbidity and mortality and is a better predictor of outcome (14,15). Many studies have attempted to identify the factors responsible for increased morbidity and mortality after fracture of the hip. Although age is considered in several risk indices, age per se is not a contraindication for surgery (15). Several authors have challenged the notion that age in isolation affects the mortality rate after fracture of the hip (16,17). In this study no deaths occurred during surgery and until discharge, demonstrating that age is not a contraindication for corrective surgery of femur. In this study twelve patients died at home during the first postoperative month. This multimodal approach, referred to as “fast-track surgery,” incorporates not only surgeons and anesthesiologists, but also as active participants of the care team. Fast-track surgery focuses on enhancing recovery and reducing morbidity by implementing evidence in the field of anesthesia, analgesia, and reduction of surgical stress, fluid management, minimal invasive surgery, nutrition, and ambulation. Several studies have reported that advancing age is associated with increased length of hospital stay after surgery for fracture of the hip. The mean length of stay on the acute orthopedic unit was not significantly different between age groups (18). The use of fast-track project allowed all 220 patients, who did not go to ICU (4 patients), above 80 years had conditions to leave hospital and go to their residence two days after surgery. Thus, in this study age did not increase the length of hospital stay. This has obvious implications for bed occupancy and cost. Spinal anesthesia blocks the sympathetic efferent nerve. The actual degree of sympathetic blockade depends on the spread of the local anesthetic. Continuous spinal anesthesia would seem an ideal anesthetic technique in the centenarians undergoing repair for hip fracture because of the possibility to slowly administer small increments of local anesthetic and, thereby, avoiding great decrease of arterial blood pressure (19). The knowledge of the orthopedic team of only experienced professionals was very important for the decision to reduce the total dose of isobaric 0.5% bupivacaine. With the adherence of some orthopedics to the project it was possible to reduce the bupivacaine dose to mean of 9.3 mg of isobaric bupivacaine, providing a lesser incidence of hypotension (2.6%), shorter duration of the block (2:44 hours), shorter stay in the PACU (2:03 hours), and reintroduction of oral feeding around 6 hours and withdrawal of venous hydration at this time. The incidence of arterial hypotension in patients over 60 years was 18% with 15 mg, reducing to 3.5% with the low doses of 10 and 7.5 mg (16). In this study with patients’ in Fourth Age using dose of 6 to 15 mg (mean 9.3 mg) of isobaric bupivacaine, the incidence of hypotension was 2.6%. The use of colloid (6% hydroxyethylamide) during the whole procedure contributed for the reduction in the incidence of arterial hypotension, even in cases of THR (20). Preoperative fluid management strategies aim to avoid the patient arriving in the operating room in a hypovolemic or dehydrated state. Multiple international guidelines, including those from the ACERTO project, allow unrestricted intake of clear fluids up to 2 h before elective surgery. In other words, allowing unrestricted access to clear fluids up to 2 h before surgery is likely to improve patient comfort and safety as it reduces thirst and hunger, does not increase gastric volumes, and reduces the acidity of gastric contents. Of the 224 patients all had a fasting time around 3 hours. This resulted in no patients entering the operating room that were hungry and only three reported thirst. No patient had nausea and vomiting during the surgical procedure. The use of 200 mL of dextrinomaltose in all 220 patients at PACU on average of 1:43 hours was not accompanied by PONV.

Anemia is very prevalent in patients undergoing surgery for an acute hip fracture. Anemia occurs as a result of the trauma, the surgery and can be preexisting in the elderly population. Anemia causes hemodynamic stress, an increased cardiac demand and potential tissue hypoxia in the elderly patients with hip fracture. Two hundred sixty-one patients were studied, and anemia was present on admission in 45% (21). The findings demonstrate that pre-surgical anemia in older hip fracture patients was significant association with a transfusion of packed red blood cells and increased hospital mortality. For hip fracture patients with trigger Hb of less than 100g/L, transfusion has been shown to reduce hospital readmission rates, but not to affect mortality or post-operative mobility scores (22). The use of transfusions may be individualized based on age, comorbid processes, life expectancy, and the nature of surgery. In the present study the trigger Hb was 100g/L, and 19 patients (8.5%) received blood during the surgical procedure, but not to affect the operative mortality. Currently, no consensus exists as to which is the best method of anesthesia employed in hip fracture surgery. The choice of anesthesia is typically based on the preferences of the patient and anesthesiologist, and the patient’s medical status. The anesthesiologist will formulate and describe a plan of care and will attain consent from the patient. Sedation may be employed in elderly in conjunction with regional anaesthesia, but careful age-related dose reduction is needed, and the feasibility of sedation is not quite elucidated. Effective pain control in the elderly patients with hip fracture is more complex than in younger patient populations. Factors that contribute to this complexity include impaired cognition, medical comorbidities, drug interactions, and problems with appropriate dosing. Pain relief during or after the surgery, may be provided by intravenous or oral medications. In certain circumstances, regional or neuraxial (epidural, spinal) nerve blocks with local anesthetics may be appropriate and can provide excellent pain relief, good functional outcome, reduced length of hospitalization and improved patient satisfaction when compared to other forms of pain relief. The relief of the post-operative pain is a pre-requisite to a better recovery and a fundamental part to the success in the implantation of a project of acceleration of Hospital discharge (21,22). Because of this, a protocol of regional anesthesia must be developed and applied, not only for surgery but also for post-operative analgesia, without intrathecal opioids. The analgesia of patients in this study was performed with lumbar plexus block (psoas compartment or inguinal), before or after surgery, with an average duration of 22 hours. With the dose employed, all patients presented residual analgesia next day to the surgery, although no one presented a motor block. Associated with lumbar plexus block, were administered fractionated doses of dypirone and tenoxicam. Such management can achieve adequate analgesia and avoid overdose or complications of certain medication (opioids).

Postoperative confusion and mental dysfunction are of great concern in the elderly patient and surgery has a significantly decompensating impact on the mental status of older persons. It may cause prolonged hospital to stay or postoperative dependence of elderly people. The definite mechanism causing delirium is not yet clear. In this study there were thirteen patients with confusion and delirium in the assessment on the first day postoperatively. Urinary retention is common after anesthesia and surgery, reported incidence of between 5% and 70% (23). Comorbidities, type of surgery, and type of anesthesia influence the development of postoperative urinary retention. Based on current evidence, a recent meta-analysis has shown that urinary catheterization during total knee arthroplasty may increase postoperative urinary tract infection and may not require routine use in these patients (24). Routine preoperative bladder catheterization may not be justified in patients with total hip arthroplasty (25). Postoperative catheterization as needed may be more cost-effective (25). The Acerto Project did not utilize opioids in spinal anesthesia to avoid catheterization, what was a routine in this type of Hospital before implantation of this project. None of the 220 patients required urinary catheter. The American Geriatrics Society placed benzodiazepines on a list of medications that should be avoided in patients over 65 years of age (26). For this reason, patient of the fourth age received 0.5 to 1 mg midazolam during the surgical procedure, and low dose of dextroketamine.

Conclusion

Etiology and pathogenesis of PCLGC are unclear, however it is proposed that repetitive microtrauma of joint and soft tissue can promote expansion of mucin from ligament fibers and acting as a potential trigger [20]. Recognition of PCLGC as a clinical entity leading knee pain and impairment is increasing due to the sensitivity of MRI to identify intra-articular abnormalities. The typical finding is an ovoid fluid filled cystic lesion which can frequently be multilocular in the intercondylar notch of the knee [22,25]. In our case report MRI shows a cystic multilocular mass with fluid signal intensity within the synovial layer of the PCL. Although most knee cysts are asymptomatic, in some case they could be a relevant source of pain [20,21]. Clinical manifestations of a knee cyst are mostly dependent on the pathologic process involved, along with its location, size, mass effect, and relationship to surrounding structures [26]. The typical presentation of symptomatic PCLGC include posterior knee pain, restriction of ROM, stiffness and mild swelling [20,21].

Limited ROM is a typical finding with an intra-articular ganglion arising from the PCL, mainly with inability and pain to extreme flexion due to the compression of the cyst mass between the PCL and the posterior joint capsule. With this clinical picture in mind, athletes between 20 and 40 years old who present knee pain with restriction on hyperextension or full flexion, with no previous macrotraumatic report or knee instability, should raise a high level of suspicion for intra-articular ganglion cysts. Only symptomatic PCLGC need to undergo treatment. There a broad spectrum of treatments described for these lesions, from a rehabilitation program focused on ROM, strengthening and proprioception to avoid kinetic impairment, to ultrasound or CT-guided aspiration or infiltration, or even arthroscopic excision. Treatment choice must take into account several criteria such as level of activity, time for recovery, risk of joint damage and recurrence of the cyst. Arthroscopic treatment has demonstrated good outcomes with up to 95% of patients reporting good results and associated with the lowest recurrence rate, but it needs an hospitalization, anesthesia and a longer recovery period, which can become a major problem when we are dealing with competitive sports [23,24].

Athletes require quick return to play with minimal side effects, so we need to take into account less invasive treatments like US or CT-guided procedures, or even load management in addition to a rehabilitation program.

Conclusion

Our treatment goal was to recover pre-injury walking ability for elderly patients with hip fractures on discharge. Since 2012, the use of the fast-track project in our hospital has successfully shortened the hospital stay after surgery by about 3 days. Living to age 80 years is no longer a rarity. In Brazil in 2018 there are four million people in the fourth age. Surgical procedures on older adults, who typically have comorbid illnesses, are clearly on the increase. Anesthesiologists and surgeons are increasingly willing to electively and emergence operate on elderly patients: the complication rate is acceptable and function may be improved to prior levels. Surgery should not be denied on the basis or age alone. Age is a minor risk factor, but comorbidity confers far more risk. Mortality of 5.3% in first month was low in first and most of those who have fractures are unlikely to regain prior physical performance. Evidence is needed to improve fracture and post fracture management in order to optimize the outcomes following fracture in patients of the Fourth Age. Enhanced recovery pathways (ERPs) have been shown to improve patient outcomes in a variety of contexts. In review provides the evidence basis for an ERP for perioperative care of patients with hip fracture (27). The implementation of the ACERTO Project in Fourth Age patients of the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS), showed that there was a marked improvement in length of stay, patient satisfaction, decreased use of bladder tube and drains, and referral to ICU, with early discharge to residence.

References

- Camarano AA (2013) O novo paradigma demográ Cien Saude Colet 18(12): 3446.

- Chong CP, Savige J, Lim WK (2009) Orthopaedic-geriatric models of care and their effectiveness. Australas J Ageing 28(4): 171-176.

- Devas MB (1974) Geriatric orthopaedics. Br Med J 1(5900): 190-192.

- Baltes P, Smith J (2006) Novas fronteiras para o futuro do envelhecimento: da velhice bem sucedida do idoso jovem aos dilemas da quarta idade. A Terceira Idade 17: 7-31.

- Greengross S, Murphy E, Quam L, Rochon P, Smith R (1997) Aging: a subject that must be at the top of world agendas. BMJ 315: 1029-1030.

- Soares DS, Mello LM, Silva AS, Martinez EZ, Nunes AA (2014) Femoral fractures in elderly Brazilians: a spatial and temporal analysis from 2008 to 2012. Cad Saúde Pública 30(12): 2669-2678.

- Ravindrarajah R, Hazra NC, Charlton J, Jackson SHD, Dregan A, et al. (2018) Incidence and mortality of fractures by frailty level over 80 years of age: cohort study using UK electronic health records. BMJ Open 8(1): e018836.

- Handoll HH, Parker MJ (2008) Conservative versus operative treatment for hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 16(3): CD000337.

- Jackman JM, Watson JT (2018) Hip fractures in older men. Clin Geriatr Med 26(2): 311-329.

- Klestil T, Röder C, Stotter C, Winkler B, Nehrer S, et al. (2018) Impact of timing of surgery in elderly hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 8: 13933.

- Imbelloni LE, Gomes D, Braga RL, de Morais Filho GB, da Silva A (2014) Clinical strategies to accelerate after surgery orthopedic femur in elderly patients. Anesth Essays Res 8: 156-161.

- Van de Ree CLP, De Jongh MAC, Peeters CMM, Munter L, Roukema JA, et al. (2017) Hip fractures in elderly people: Surgery or no surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation 8: 173-180.

- COM/News (2019) The emergence and challenges of the fourth age. Fabio Nóbrega on 04/28/19 at 7:30 am Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

- Thomas DR, Ritchie CS (1995) Preoperative assessment of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 43: 811-821.

- Miller DL (1995) Perioperative care of the elderly patient special considerations. Cleve Clin J Med 62: 383-390.

- Kenzora JE, McCarthy RE, Lowell JD, Sledge CB (1984) Hip fracture mortality: relation to age, treatment, preoperative illness, time of surgery, and complications. Clin Orthop 186: 45-56.

- Mossey JM, Mutran E, Knott K, Craik R (1989) Determinants of recovery 12 months after hip fracture: the importance of psychosocial factors. Am J Public Health 79: 279-286.

- Holt G, Macdonald D, Fraser M, Reece AT (2006) Outcome after surgery for fracture of the hip in patients aged over 95 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br 88-B: 1060-1064.

- Imbelloni LE, Beato L (2002) Comparison between spinal, combined spinal-epidural and continuous Spinal anesthesia for hip surgeries in elderly patients. A retrospective study. Rev Bras Anestesiol 52(3): 316-325.

- Hamaji A, Hajjar L, Caiero M, Almeida J, Nakamura RE, et al. (2013) Volume replacement therapy during hip arthroplasty using hydroxyethyl starch (130/0.4) compared to lactated ringer decreases allogeneic blood transfusion and postoperative infection. Rev Bras Anestesiol 63: 27-35.

- Puckeridge G, Terblanche M, Wallis M, Fung YL (2019) Blood management in hip fractures; are we leaving it too late? A retrospective observational study. BMC Geriatrics 19(1): 79.

- Halm EA, Wang JJ, Boockvar K, Penrod J, Silberzweig SB, et al. (2003) Effects of blood transfusion on clinical and functional outcomes in patients with hip fracture. Transfusion 43: 1358-1365.

- Baldini G, Bagry H, Aprikian A, Carli F (2009) Postoperative urinary retention: anesthetic and perioperative considerations. Anesthesiology 110: 1139-1157.

- Ma Y, Lu X (2019) Indwelling catheter can increase postoperative urinary tract infection and may not be required in total joint arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 20(1): 11.

- Iorio R, Whang W, Healy WL, Patch DA, Patch DA, et al. (2005) The utility of bladder catheterization in total hip arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 432: 148-152.

- American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (2015) American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 63: 2227-2246.

- Silez A, Childers CP, Faltermeir C, Singer ES, Hu L, et al. (2018) Surgical technical evidence review of hip fracture surgery conducted for the AHRQ safety program for improving surgical care and recovery. Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation 9: 1-11.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...