Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6695

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6695)

Knowledge of the Nursing Team of Intensive Care Units on Palliative Care Volume 2 - Issue 4

Josemar Batista*, Midiam de Freitas Oliveira, Larissa Marcondes, Marinete Esteves Franco, Bruna Tres and Bruna Eloise Lenhani

- Santa Cruz College, Brazi

Received: January 17, 2020; Published: January 27, 2020

Corresponding author: Josemar Batista, Santa Cruz College, Brazil

DOI: 10.32474/LOJNHC.2020.02.000142

Summary

Objective: To identify the knowledge of the nursing team about palliative care in Intensive Care Units of a private hospital in Brazil.

Method: Cross-sectional and quantitative performed in two Intensive Care Units, with application of an instrument validated to 79 professionals in September 2019. Questions with correct answers ≥ 90% represented satisfactory knowledge, between 70% and 89% moderate and ≤ 69% unsatisfactory.

Results: Among the professionals, 55.7% had moderate knowledge and 43% unsatisfactory knowledge. Professionals are unaware that palliative care should be based on principles and not protocols with prevalence of errors/were not able to answer 67.1%. Five questions scored satisfactorily, with emphasis on the issue “Reducing pain and human suffering are care addressed in palliative care” that obtained an index of 100% of correct answers.

Conclusion: The knowledge of nursing professionals about palliative care was considered moderate to unsatisfactory, requiring educational actions to progress the level of knowledge of the nursing team on the theme.

Keywords: Knowledge; Nursing; Palliative Care; Intensive Care Units

Introduction

The International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care defines that palliative care is active holistic care, offered to people of all ages who are in intense suffering related to their health, arising from serious illness, especially those who are at the end of their lives, whose objective is to improve the quality of life of patients, their families and their caregivers. [1] Access to this care model is an emerging challenge and global health priority, mainly due to the increasing population aging combined with chronic Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs). [2] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), NCDs are the main causes of death, representing 71% of the 57 million deaths worldwide. In 2016, cerebrovascular diseases, cancers and chronic respiratory diseases accounted for 54% of total DEATHS from NCDs, becoming one of the main health challenges of the current century. [3] In addition, it appears that dementia deaths more than doubled between 2000 and 2016, making it the 5th leading cause of global death in 2016. [4] This trend is also followed in Brazil, in which 74% of all deaths were caused by NCDs. Cardiovascular diseases and cancers were 28% and 18% of proportional mortality in 2016, respectively. [3] In the face of the current health model, the Lancet Commission’s report on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief designed the need for palliative care to minimize the suffering caused mainly by malignant neoplasms, cerebrovascular diseases, lung diseases and dementias. This report estimated that by 2060 48 million people (47% of all deaths worldwide) will die from serious health problems, an increase of 87% compared to 26 million people in 2016. Overall, the burden of human health-related suffering will increase among people aged ≥70 years, driven by increased dementia. [2] These data foster the need to develop strategies to improve health services in the integralization of palliative care in order to meet the growing needs of the population and alleviate human suffering. [5] In this perspective, a deeper look is needed in relation to the suffering of individuals in their terminality, having as its starting point the integrality of care. Understanding the current and future needs of the population becomes palliative care as an urgent possibility in the face of health challenges worldwide and nationally. This care aims to prevent and alleviate human suffering in its various dimensions [6], which must necessarily be mediated by a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary health team. [7] Palliative practice is underdeveloped and of low quality in most of the world, especially in countries situated on the shores of North America, Europe and Australia. [8] Despite the shyness of the theme in the context of Intensive Care Units (ICUs), the principles of palliative care have been gaining space in discussions in these environments as one of the alternatives of care for incurable patients. [9] In this sense, it is believed that to improve palliative practice, it is assumed that in addition to the structural and budgetary aspects, the knowledge of the health team, especially nursing professionals, are relevant to implement and disseminate actions directed to care, which must be individualized and planned according to the evolution of the patient’s disease, with a view to relieving human suffering, providing comfort and dignity to the patient and family members. In view of the above, it is questioned: What is the knowledge of the nursing team about palliative care in ICUs? The aim of this research was to identify the knowledge of the nursing team about palliative care in ICUs of a private hospital in Brazil.

Method

Cross sectional research conducted in two private hospital ICUs in a capital in southern Brazil. It is a general hospital with as anchor services the Cardiology Service, Cardiac Surgery, hospital hospitalist, orthopedics and urology. It is an important medical center of the State of Paraná, totaling 168 beds. Of these, 24 beds are for the clinical and surgical care of critically ill patients. The target population consisted of nursing professionals crowded and working in the units surveyed corresponding to 89 workers. To compose a non-probabilistic and intentional sample, all professionals were invited to participate through the following inclusion criteria: being nurse and/or nursing technician with interaction or direct care to the patient, with a minimum workload of 36 hours/weekly, and minimum working time of three months in the units studied. Professionals who were on vacation, paid leave and medical certificate were excluded. Data collection took place in September 2019, in the workplace itself at the beginning of all shifts by a single researcher. All professionals were informed regarding the objective of the research and voluntary participation and prior signing of the Free and Informed Consent Form (TCLE). To the one who agreed to participate, an envelope containing two pathways of the TCLE and two questionnaires prepared by the researchers were delivered. Questionnaire I am composed of variables related to the characterization of participants (gender, age, professional category, work shift, training time, ICU performance and learning is poorly on palliative care). Questionnaire II, based on the precepts of the National Academy of Palliative Care [10] and the Manual of the Palliative Care Residence [11] was denominated as “Palliative Care Questionnaire for Intensive Care Unit Nursing Professionals(QCPPE-ICU)”,consisting of 20 assertions related to conceptual and atitudine aspects on care Palliative. Such variables are measured in the model of true and false. Each correct answer (V or F) is worth 0.5 points. The score top or equal 90 points (90%) is considered with satisfactory knowledge; between 70 and 89 points (70% and 89%) moderate, and equal to or less than 69 points (69%) as unsatisfactory knowledge. For validation of questionnaire II, a minimum agreement reliability index of 80% was adopted in each item and for the entire instrument [12]. This presented a Content Validity Index (IVC) of 88.6% and Cronbach’s overall Alpha was 0.81. The completed questionnaires were returned directly to the researcher and encoded with letter P (Participant) following the number of the return of the questionnaire (P1, P2... PX) with a view to ensuring the anonymity and confidentiality of the data. The data was typed into a spreadsheet in the Microsoft Office Excel 2016 program, by double typing and fixes of possible inconsistencies. The data were analyzed by descriptive statistics for the characterization of categorical and continuous variables, described by mean, median, absolute and relative frequencies. The research was extracted from the project entitled “Andfetishity of educational interventions in the unto nursing team age of Therapy Intensive on palliative care”, with approval by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee, under the opinion of No. 3,400,548.

Results

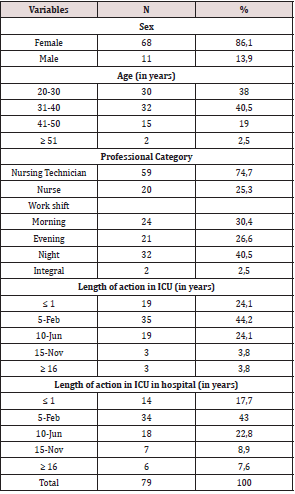

Table 1: Distribution of the sociodemographic and labor characteristics of nursing professionals in intensive care units. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, 2019.

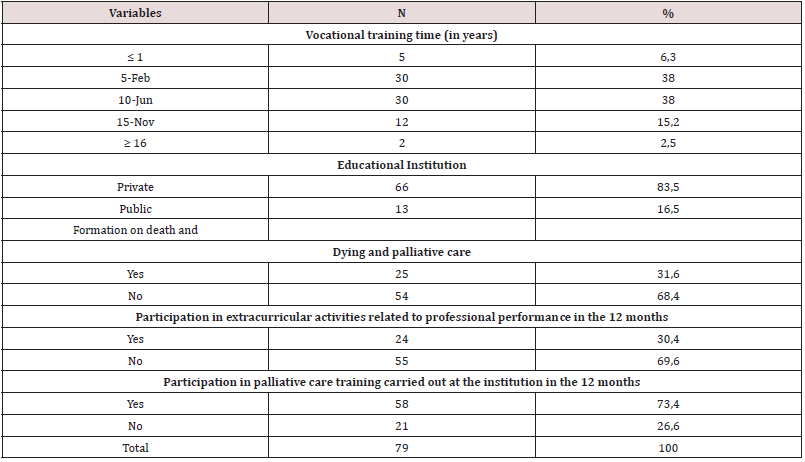

Participants were 79 nursing professionals, which corresponds to a response rate of 88.8% of the total population. The mean age, in years, was 34.2 and median of 34years. The sociodemographic and labor profile of the nursing team is presented in (Table 1). There is a prevalence of nursing technicians (n=59;74.7%). It was found that 68.4% (n=54) of nursing professionals reported incipience of information about the process of death and dying and palliative care during their professional training as indicated in (Table 2). Of the 24.4% (n=19) professionals who were post-graduates (specialization level), 68.4% (n=13) had specialization in the ICU area.

Table 2: Distribution of the responses of nursing professionals of intensive care units, according to professional and academic training. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, 2019.

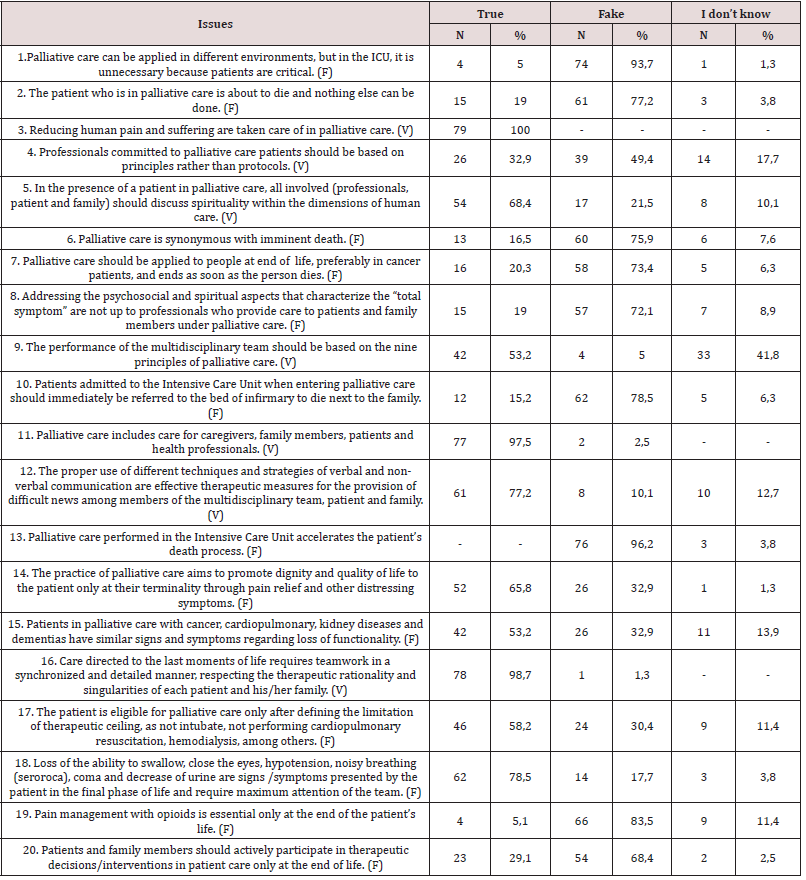

Regarding the individual knowledge of the professionals, this was moderated with 55.7% (n=44), unsatisfactory with 43% (n=34), with only one participant who achieved satisfactory knowledge correcting 90% of the questionnaire. Regarding the conceptual and attitudinal aspects of palliative care was considered unsatisfactory (correct answers ≤ 69%) on eight questions. Five questions scored satisfactorily, with emphasis on the issue “Reducing pain and human suffering are care addressed in palliative care” that obtained a 100% correct rate (Table 3).

Table 3: Distribution of nursing professionals’ responses to conceptual and attitudinal aspects of palliative care in Intensive Care Units. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, 2019.

Discussion

The use of QCPPE-UTI made it possible to measure the knowledge of the nursing team regarding conceptual and attitudinal aspects of palliative and therapeutic care in the ICU. The data allowed to identify that knowledge was considered moderate and unsatisfactory with regard to palliative care in these units. However, the nursing team recognizes that palliative care is necessary in the ICU and stated that patients in this type of care are not about to die, disagreeing that this care accelerates the process of death. This data corroborates an integrative review by pointing out knowledge deficits, but favorable attitudes of nurses in relation to theme [13] in the same way as the need to expand the theoretical and practical teaching of palliative care in the curricula of undergraduate health courses, and to encourage research aimed at improving this training, [14] in particular by the in nopia of specific guidelines to guide professional education. In this sense, incorporating principles and interventions of palliative care in the daily practice of the ICU team are increasing demands, given, the benefits of this care to patients and family members as well as for health professionals in conflict resolution in terminal situations, with a view to ensuring palliative care of excellence capable of successfully meeting the needs of family members and patients with incurable diseases. [15] I offer assistance based on the principles of palliative care requires a direct or indirect support system that allows the patient to live as actively as possible, until the moment of his death, providing organized and humanized support to assist patients and their families. [16] However, in order for this to develop properly to have qualified professionals and knowledgeable of the principles discussed is indispensable. Unanimously, it was evidenced that the nursing team recognizes that reducing pain covers palliative care, possibly because it is a basic topic to minimize human suffering and be a care more likely to be conceived among the attributions of these professionals, whether palliative care, or not, since the process of academic training. In a study conducted with 104 nurses from 12 ICUs in five hospitals in a capital in northeastern Brazil revealed that among the principles that were most relevant to nursing care practice were to relieve pain and other associated symptoms [17], which denotes the need for this care to be managed by the health team, mainly, nursing in the context of intensive practices.

It is argued that pain, especially chronic pain, is not properly treated and documented by inadequate initial evaluation by the health team. In some cases, the patient is unable to communicate his pain and the health professional should be aware of the signs shown to adopt assertive conducts to achieve the effective treatment of this symptom, especially for those patients in the final phase of life. [18] On the other hand, approximately half of the professionals were unable to relate the signs and symptoms related to the loss of functionality to the types of diagnoses and did not know how to answer the signs and symptoms presented by the patient to become eligible for palliative care. It is known that patients in palliative care during the disease, regardless of the stage in which they are, present one or more symptoms, resulting from physical, psychic, social and spiritual alterations. Thus, it is of fundamental importance that all professionals involved with palliative care present specific knowledge to identify them as, for example, in the application of scales developed and validated for this population, whose purpose is to direct care and obtain effectiveness in reducing distressing symptoms, becoming effective tools to identify the loss of functionality in the different phases of nursing care to patients in palliative care. [18] Expanding in the analysis of this statement, it is worth mentioning that in the question “The practice of palliative care aims to promote dignity and quality of life to the patient only in their terminality through pain relief and other distressing symptoms”, it proved unsatisfactory, in approximately 66% of the nursing team, which evidences deficit in front of the understanding about palliative practice. It is noteworthy, in this sense, that the professionals surveyed expressed incipience of information about the process of death and death and palliative care during their professional training. It is imperative to insert discipline into the theme addressed in the curriculum of nursing courses with a view to enabling and qualifying professionals in the provision of comprehensive and humanized care in the health and disease process, relating theory and practice effectively, a factor considered essential for the development of fundamental competencies to practice nursing practice in the principles that shape palliative care. [19] In the present study, there was a prevalence of professionals who could not identify the symptomatology presented by the patient in the final phase of life. This result draws attention, since 73.4% of these professionals said they had participated in palliative care training performed at the institution in the last 12 months, indicating the need to address this aspect in subsequent continuing education. Another data refers to their lack of knowledge about palliative therapy based on principles rather than protocols. A study with the application of the Palliative Care Quiz for Nursing (PCQN) to 159 nursing professionals working in a university general hospital in Spain indicated that errors in the scale of philosophy and principles of palliative care was 36.3%. [20] These unsatisfactory results can be translated with the perception of professionals in view of the organization of nursing services in the use of protocols to direct the development of activities and technical procedures.

From this perspective, it is understood that care protocols are necessary technologies that are part of the organization of nursing work and constitute an important health management instrument. [21] However, the principles that guide palliative care bring a clarification to both health professionals and family members with regard to the very perception of life and death and its dignity in individualizing and not standardizing care. Regarding spirituality, the participants stated that this is an important and integral part in palliative care and believe that it is the competence of health professionals who provide care to patients and family members to address psychosocial and spiritual aspects, which corroborates a study conducted in a philanthropic hospital in a municipality in northeastern Brazil, with 10 nurses, in which it showed that these professionals recognized the importance spiritual dimension in the care of patients under palliative care, contributing to improve the acceptance of the finite process. [22] Thus, it is imperative that palliative care in the context of ICUs be conducted by qualified team in that area, providing clarity and understanding of the various aspects involving the patient and enabling assertive decisions regarding palliative susiativism, including early directives of will. In this perspective, effective communication becomes essential because it favors understanding about diagnosis, determining decisions and managing conflicts, both for patient health issues and for the health of family members during the mourning period. [23] In the present research, the nursing team points out the importance of teamwork, which should occur in a synchronized and detailed way, directed in the last moments of the patient’s life, and recognize the need to use techniques and strategies to strengthen the communication of difficult news. That is, if the multidisciplinary team is trained for the communication of bad news, this will be the beginning of palliative care, providing transparency in communication and establishing a bond of trust with the team. [23] It is known that communication is an indispensable process in human relations and essential to scale individualized care and obtain qualified assistance. For this, the implementation of effective communication between nurses, patients and family is immensely relevant, to evaluate and better know the patient and his needs, with agility and understanding, and thus enable special therapeutic assistance.

[24] This circumstance, which highlights the need of the ICU team to improve their communication skills, to know what, how and when to talk, as well as the time to shut up and listen to patients and family members, showing solidarity with the pain of the other, [23] in particular, because effective communication between the ICU team and family members can contribute, in a preponderant way, to decision making, and be associated with reducing the intensity of care at the end of life with family suffering. [25] The results, presented here, indicate fragility in the understanding of professionals in view of the need for active participation of patients and family members in decision-making and therapeutic interventions in all phases of palliative care. In this context, the patient should cease to be a mere object of care to actively participate in decision-making about procedures, interventions and treatments. [26] This does not mean mere transfer of responsibility, but rather to offer care centered on the person in order to promote dignity and enable autonomy and exercise of their choices. [27] From this same perspective, inserting family members into the terminality process is a form of respect for bioethical principles. The family is one of the structuring axes of care for patients outside of therapeutic possibilities of cure occupying a place of protagonist and being also integrated into the care team, [28] of which are up to the professionals involved to address all issues that may intervene in the non-acceptance of the patient’s finite condition. Professionals who work with palliative care, on the one hand, increasingly need to improve their knowledge about this theme, with a view to minimizing suffering and offering quality of life, comfort and dignity through the care provided, but on the other hand, they need to understand that advancing principles and palliative philosophy require time and continuing education for changes to occur and impact on professional practice.

Conclusion

The knowledge of nursing professionals about palliative care was considered between moderate and unsatisfactory, especially regarding the principles and identification of signs and symptoms related to the loss of functionality. It is expected that the results presented can serve as a parameter in the contribution of professional training and continuing education, with a view to developing actions to promote a better understanding of health and nursing professionals and academics on the theme in the context of ICU nursing care, as well as to stimulate other related research. As a limitation, it is emphasized that other statistical tests for the validation process of the questionnaire are not emphasized, and the fact that the research was carried out in a single hospital making it impossible to generalize the results.

References

- Global Consensus based palliative care definition. Houston: IAHPC 2018 (2019) International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC).

- Sleeman KE, Brito M, Etkind S, Nkhoma K, Guo P, et al. (2019) The escalating global burden of serious health related suffering: Projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health 7(7):883-892.

- Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. (2018) World Health Organization (WHO) pp: 223.

- 10 leading causes of death in the world. (2018) Pan American Health Organization.

- Centeno C, Arias Casais N (2019) Global palliative care: From need to action. Lancet Glob 7(7): 815-816.

- Mitchell S, Tan A, Moine S, Dale J, Murray SA (2019) Primary palliative care needs urgent attention. BMJ 365: 1827.

- Gomes ALZ (2016) Othero MB Palliative Care. Estud Av 30(88):155-166.

- Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. London: Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. (2014) World Health Organization (WHO) pp: 111.

- Coelho CBT, Yankaskas JR (2017) New concepts in palliative care in the intensive care unit. Rev bras ter intensiva 29(2):222-230.

- RT Oak, Parsons, HÁ (Org.) (2012) ANCP Palliative Care Manual. 2nd (edn.) São Paulo: sn, Brazil.

- RT Oak, Souza MR, Franck EM, Polastrini RTV, Crispim D, et al. (2018) Manual of residence in palliative care. Barueri: SP, Manole.

- Pasquali L (1998) Principles of drawing up psychological scales. Rev psiquiatr clín 25(5):206-213.

- Achora S, Labrague LJ (2019) An Integrative Review on Knowledge and Attitudes of Nurses Toward Palliative Care: Implications for Practice. J hosp palliat nurs 21(1):29-37.

- Costa AP, Poles K, Silva AE (2016) Palliative care training: Experience of medical and nursing students. Interface comun saúde educ 20(59):1041-1052.

- Mercadante S, Gregoretti C, Cortegiani A (2018) Palliative care in intensive care units: Why, where, what, who, when, how. BMC Anesthesiol 18(106).

- Verri ER, Bitencourt NAS, Oliveira JAS, Santos Júnior R, Marques HR, et al. (2019) Nursing professionals: Understanding about pediatric palliative care. Rev enferm UFPE online 13(1):126-136.

- Cavalcanti IMC, Oliveira LO, Macêdo LC, Leal MHC, Morimura MCR, et al. (2019) Principles of palliative care in intensive care from the perspective of nurses. Rev 10(1):1-10.

- Santos JM (2016) Symptom control in palliative care. In: Nursing in palliative care/Organization: Maria do Carmo Vicensi, et al. (Edt.), Florianópolis: Regional Nursing Council of Santa Catarina: Editorial Letter.

- Rao Cross, Arruda AJCG, Agra G, Costa MML, Nóbrega VKM (2016) Reflections about the palliative care in the nursing graduation context. Rev enferm UFPE online 10(8):3101-3107.

- Chover Sierra E, Martínez Sabater A, Lapeña Moñux Y (2017) Knowledge in palliative care of nursing professionals at a Spanish hospital. Rev Latinoam is sick 25:e2847.

- Krauzer IM, Dall'Agnoll CM, Gelbcke FL, Lorenzini E, Ferraz L (2018) The construction of assistance protocols in nursing work. REME rev min enferm 22:e1087.

- Evangelista CB, Lopes MEL, Costa SFG, Abrão FMS, Batista PSS, et al. (2016) Spirituality in patient care under palliative care: A study with nurses. Esc Anna Nery Rev Enferm 20(1):176-182.

- Bastos BR, Fonseca ACG, Pereira AKS, Silva LCS (2016) Training of Health Professionals in the Communication of Bad News in Palliative Care Oncology. Rev Bras 62(3):263-266.

- Andrade GB, Pedroso VSM, Weykamp JM, Soares LS, Siqueira HCHS, et al. (2019) Palliative Care and the Importance of Communication Between Nurse and Patient, Family and Caregiver. Rev Fund Care Online 11(3):713-717.

- Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, Gold J, Ciechanowski PS, et al. (2016) Randomized Trial of Communication Facilitators to Reduce Family Distress and Intensity of End-of-Life Care. Am j respir crit care med 193(2):154-162.

- Monteiro RSF, Silva Junior AG (2019) Advance Directive: Historical course in Latin America. Rev bioét 27(1):86-97.

- Kovács MJ (2014) On the way to death with dignity in the 21st Rev bioét 22(1):94-104.

- Matos JC, Borges MS (2018) The family as a member of palliative care assistance. Rev enferm UFPE online 12(9):2399-406.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...