Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6695

Review article(ISSN: 2637-6695)

Intervening Practices for Cyberbullying Prevention Volume 1 - Issue 2

Gilberto Marzano*1,2,Joanna Lizut22

- 1Rezekne Academy of Technologies, Latvia

- 2Janusz Korczak Pedagogical University, Poland

Received: March 14, 2018;; Published: May 02, 2018

Corresponding author: Gilberto Marzano, Rezekne Academy of Technologies, JanucsKorczak Pedagogical University in Warsaw, Poland

DOI: 10.32474/LOJNHC.2018.01.000108

Abstract

The Internet is a hugely vast, intriguing world, difficult to penetrate in depth, rich with dissimulations, full of useful but also evil things, that is continuously changing. Cyberbullying represents a palpable risk, especially for the online generation who is constantly connected and uses the internet to socialize. The first step for the prevention of cyberbullying is the acquisition of knowledge of what cyberbullying is and how it occurs within a specific context. This is no easy task, since cyberbullying is a complex and creeping new phenomenon, so much so that researcher’s opinions are often divided as to its definition, and there is a lack of agreement on many aspects concerning it. This article presents and comments on some cyberbullying preventing strategies and tips, and is devoted to educators engaged in cyberbullying prevention.

Keywords: Cyberbullying; Cyberbullying prevention; Online wellbeing; New media risks; Cyberspace threats; Cyberbullying and technology

Introduction

The internet has changed our life but human nature has remained essentially the same, and we may assume that it will remain the same in the near future. Accordingly, the spread of the new technologies has multiplied the risks and threats for the internet user since cyberspace is not forbidden to cheats, perpetrators of evil deeds, and individuals who like to harm, harass, and victimize other people, particularly those who are weak and vulnerable. Cyberbullying is an alarming phenomenon closely connected with the relational changes introduced by the new digital technologies and online communication. Indeed, a large part of young people are continuously connected with their peers and use social networks to communicate amongst themselves, sharing all sort of experiences, emotions, and personal secrets. For this reason, the majority of victims of cyberbullying are children and adolescents, and recent statistics reveal this bleak situation1 .

a) 25 per cent of teenagers report that they have experienced repeated bullying by phone or on the internet;

b) 52 per cent of young people report that they have been cyber bullied;

c) 11 per cent of adolescents and teens report that embarrassing or damaging photos of them have been taken and posted on the internet without their knowledge or consent;

d) 10 per cent of all middle school and high school students have received threatening, offensive, or hateful messages;

e) 55 per cent of all teens that use social media have witnessed outright bullying online.

How, then, can we combat the evil phenomenon of cyberbullying? Some years ago, Hinduja & Patchin indicated the top ten tips for educators aimed at preventing cyberbullying. These tips can be grouped into three main classes: Contextualized knowledge acquisition (tip: Formally assess); Educational activities (tips: Teach students that all forms of bullying are unacceptable; Specify clear rules regarding the use of the Internet and electronic devices;

Use peer mentoring; Cultivate a positive school climate; Educate your community); Technical support (tips: Consult with your school attorneys before incidents occur; Create a comprehensive formal contract; Implement blocking/filtering software; Designate a “Cyberbullying Expert”)

The educational activities class includes five of the ten prevention tips, showing the importance that education occupies in promoting appropriate solution strategies. In the following paragraphs, the current strategies of cyberbullying prevention, including Hinduja & Patching’s tips2, are analyzed and commented on. However, before dealing with cyberbullying prevention, we cannot omit to tackle the issue of what cyberbullying actually is. Indeed, many forms of cyberbullying correspond to traditional harmful and aggressive behavior. Nevertheless, the internet offers perpetrators new and powerful means to harass their victims. The appropriation of these new means is only an aspect of cyberbullying, since the technology has extended the opportunity to harm people without physical contact, increasing the range of stalkers and harassers.

What Cyberbullying Is

Currently there is a debate about what constitutes cyberbullying, and how this phenomenon is similar or different to traditional forms of bullying Thomas [1], Menesini et al. [2].

Beran [4]3 referred to cyberbullying using the expression “old wine in new bottles”. The hypothesis of contiguity between bullying and cyberbullying seems to be confirmed by some researchers’ data Ybarra [5]; Beran [6]; Limber [7]; Del Rey [8]. This data reveals that there is an overlap of 44% between victims of “online aggression” in cyberspace and real-life victims. In particular, Beran [6], as well as Kowalski and Limber, found an overlap of around 60% between being a victim in real life and being a victim of cyberbullying – although, if 60% of cyber-victims are also bullied in “real life”, that leaves 40% of victims who are not bullied in real life. Data from a German study Riebel [9] confirms that more than 80% of cyberbullies bully their fellow students in real life as well; although in most cases it seems that cyberbullying is merely an additional strategy in the repertoire of a typical bully.

Beran [4]3 referred to cyberbullying using the expression “old wine in new bottles”. The hypothesis of contiguity between bullying and cyberbullying seems to be confirmed by some researchers’ data Ybarra [5]; Beran [6]; Limber [7]; Del Rey [8]. This data reveals that there is an overlap of 44% between victims of “online aggression” in cyberspace and real-life victims. In particular, Beran [6], as well as Kowalski and Limber, found an overlap of around 60% between being a victim in real life and being a victim of cyberbullying – although, if 60% of cyber-victims are also bullied in “real life”, that leaves 40% of victims who are not bullied in real life. Data from a German study Riebel [9] confirms that more than 80% of cyberbullies bully their fellow students in real life as well; although in most cases it seems that cyberbullying is merely an additional strategy in the repertoire of a typical bully.

An aggressive, intentional act carried out by a group or individual, using electronic forms of contact, repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend him or herself Smith et al. [30]. [cyberbullying is when someone] repeatedly makes fun of another person online or repeatedly picks on another person through e-mail or text messages or when someone posts something online about another person that they don’t like Hinduja & Patchin [31]. Cyberbullying involves the use of information and communication technologies to support deliberate, repeated, and hostile behavior by an individual or group that is intended to harm others Belsey [32]. Although there is a high degree of empirical and conceptual overlap between traditional bullying and cyberbullying specific, distinct features have been identified in cyberbullying Dooley [19]; Smith et al. [30]. Cyberbullies can reach particularly large audiences within a peer group as opposed to the small groups who are the usual audience in cases of traditional bullying. Compared to the more traditional forms of bullying, the person carrying out acts of cyberbullying may be less aware or is completely unaware of the consequences of their actions. In our opinion, two issues, which are specific to cyberbullying, continue to create many theoretical and practical difficulties. The first is related to the lack of complete control, which is due to the technology being used. For example, a harmful digital content (SMS, text, picture, or video) can, once sent out or uploaded to the internet, be downloaded, forwarded, and diffused by anyone, not only the initial perpetrator, and the flow cannot be stopped. Furthermore, the victim can experience the same aggression many times, accessing and running the same toxic digital item repeatedly. The internet’s memory is out of the control of both the perpetrators and the victims, and cyberbullies can take advantage of the specific features of online communication (anonymity, asynchronicity, and accessibility) to torment their targets Valkenburg [33].

The second issue is related to the notion of power imbalance, which can involve different spheres of domination and weakness Law [34]. In fact, one can presume that cyberbullies have a very deep knowledge of technologies and profit from their anonymity. But things could go in a different way: cyberbullies might be less technologically skilled than their victims, using technologies only as an extension of their face-to-face aggression or to document it. Conversely, it has been observed that the hidden nature of electronic communication can offer to victims, or self-presumed victims, of traditional bullying the opportunity to retaliate online or to attack their real-world bullies Kowalski [7]. An online survey conducted on 473 students König [35] investigated the role of revenge and retaliation as a motive for engaging in acts of cyberbullying. The data showed that 149 respondents were identified as traditional victims/cyberbullies, and that, although individual differences played a role in their choice of victims, traditionally bullied students did indeed tend to choose their former perpetrators as cyber-victims.

Foot Note:2Hinduja and Patching’s tips have been commented on in a previous publication Marzano [3].

3Robert S Tokunaga 2010 for conceptual definitions of cyberbullying used in research.

4http://www.njleg.state.nj.com/2010/Bills/PL10/122.PDF.

In our opinion, cyberbullying is an extremely complex issue. In general, it can assume two different faces due to the different use of communication technology. Online bullying can merely represent a simple, albeit really serious, extension to face-to-face bullying: “new wine in old bottles”. Victims know their perpetrators and the dynamics between perpetrators and victims are the same ones as in traditional bullying. However, there is another aspect of cyberbullying that is new and more difficult to probe, due to the nature of virtual relationships and the significance of perception of these kinds of relationships. Indeed, the internet has extended the sphere of possible relationships, creating a new space-temporal dimension. Accordingly, cyberbullying becomes sneaky and dangerous, since it involves the sphere of intimacy, and particularly the image that young people have of themselves. Furthermore, young people use digital technology as the dominant medium for communicating amongst themselves. But between these two different patterns of cyberbullying there are many other forms which are context-dependent and involve the individual personality of the various implicated actors (perpetrators, victims, bystanders, educators, and parents), and also involve cultural factors, since culture and historical heritage can influence cyberbullying, or at least its perception:

An Important consideration to keep in mind when comparing studies are cultural similarities and differences in both the prevalence of research on the topic of cyberbullying and the prevalence of cyberbullying itself within a particular culture Agatston [36]. We must note, here, a new serious phenomenon of so-called revenge pornography, or revenge porn that is recently spreading. It involves a perpetrator – typically an ex-partner from a previous romantic relationship – uploading nude, semi-nude, or sexy images/videos of the ex-partner to the internet without the person’s consent. In developing an effective educational nocyberbullying program, these different aspects of the problem cannot be ignored. There is a broad consensus within the literature that the definition of cyberbullying must be based on the criteria of intentionality and power imbalance. It has been observed that the issue of repetition is still open and needs further investigation, depending on the direct and indirect nature of the attack Menesini et al. [37].

Indeed, automatic repetition or repetition caused by forwarding messages or videos is new aspects that should be considered. Nevertheless, in our opinion, repetition intended both as reiteration and as intentional diffusion of hurtful contents should be included in the cyberbullying definition. The New Jersey Anti- Bullying Bill of Rights Act 2010 defines harassment, intimidation, or bullying as: “any gesture, any written, verbal, or physical act, or any electronic communication, whether it be a single incident or a series of incidents”.5 A similar definition has been introduced into Italian legislation in 2016. 6Patchin & Hinduja disagree with these definitions, although they do recognize the “state’s desire to account for a variety of types of harmful behaviors” Patchin & Hinduja [38]. In fact, the above definitions appear to be motivated by the preoccupation of the legislator with establishing policies that disincentive bullying acts but risk extending the scope of bullying beyond measure. Furthermore, in defining policies against cyberbullying, we should make a distinction between the playful exchange of ridiculing remarks amongst friends and bullying. It is difficult to determine when a certain behavior crosses the line and becomes bullying. In this regard, we can consider the following story by Walker [39]: Jess didn’t think anything of it when she texted David, her friend Laura’s crush, about the math homework. But when Jess went on Facebook later, her heart dropped. Laura and their friend Allie had created a “We Hate Jess” page, where they accused Jess of moving in on David. Jess’s eyes filled with tears. How could her friends post such hateful comments?7 For Walker, this story is both bullying and drama indeed it is drama since “Laura and Allie feel they’ve been wronged, so they’re not just targeting Jess for no reason”. But the internet has changed the drama of bullying at the point when Laura and Allie created the web page and made their feelings against Jess public.

Contextualized Knowledge Acquisition

The first of the ten top tips for educators indicated by Hinduja & Patchin is knowledge acquisition of the extent and the scope of the problem within the school district. They suggest collecting survey and/or interview data from students in order to acquire a baseline measure of what is happening in the school. Acquiring contextualized knowledge is the necessary premise for implementing specific countermeasures against cyberbullying. The surveys should primarily be aimed at collecting information useful to educate students and staff about online safety and the use of the internet in a creative and powerful way. However, in our opinion, understanding the school’s context should not be limited to gathering data regarding off-line and on-line bullying amongst students, but should also be extended to acquire information about the level of staff awareness regarding violent conduct within their school and their competence at tackling it. Although teachers are aware and well prepared on critical media literacy, they are often considered incompetent in computing and new media use by their students. In contrast, more than 90% of today’s students are using computers and smartphones to access and disseminate media.

Foot Note:5Law no. 71 of May 29th 2017.

6http://choices.scholastic.com/story/it-bullying-or-drama.

7In Italy, two 15 years old girls, who, in 2013, murdered a 67-year-oldman, recounted to an unknown boy they casually encountered on a train: “It was like we were within GTA, the video game. We felt like the hero of the game”.

Teachers and educators’ awareness as to what constitutes bullying/cyberbullying can vary Kochenderfer [40] and requires a wide base knowledge of diverse aggressive features. Many of these are subtle, hidden, and undetectable, but have devastating consequences. In fact, overt violence is a key factor that is easy to recognize, but there are also forms of relational aggression which are covert, such as exclusion and sly mocking Ryan et al. [41]; Sahin [42]. A lack of knowledge of bullying-type behaviors can cause teachers to underestimate relational aggression, making them unlikely to intervene if such problems occur. For this reason, assessing the capability of school staff at recognizing the spectrum of bullying behaviors is a primary step to dealing with bullying issues Craig [43]. Strategies and techniques used for data gathering regarding students’ behavior and teachers’ awareness and skills in relation to off-line and on-line bullying are also important.

The most suitable and widely utilized means for gathering data are questionnaires. In the case of bullying and cyberbullying it is necessary to prepare the questionnaire carefully and provide some preliminary actions. It is crucial that school staffs are involved in preparing and submitting the questionnaire with detailed instructions and appropriate suggestions. Students should be informed that it is not mandatory to complete the questionnaire, but that the school would be grateful if they did. Furthermore, they should be assured that anything that they write will be treated as absolutely confidential: the questionnaire’s anonymity will be preserved, and teachers, the head teacher, and classmates will not be shown their responses. It is of the utmost importance to underline that the answers be truthful, explaining that the reason for the questionnaire is to pursue the students’ best interests, to protect them and make the school a safer place. Students should be involved in conducting the survey and be motivated to share their advice, following a process that is participatory and encourages responsible engagement. Many good templates exist that can be used for gathering data regarding the presence of bullying and cyberbullying at school, and for measuring the level of awareness and skill of school staff at tackling such phenomena. Generally, questionnaires focus on the life of students both in and out of school over the preceding 2 or 3 months; students are invited to answer the questions by reflecting on how their lives have been during the past couple of months and not only on how it is at the present time. Often designed for scientific aims, many questionnaires premise the definition or explanation of the word bullying:

We say a student is being bullied when another student, or several other students

a) Say mean and hurtful things or make fun of him or her and call him or her mean and hurtful names;

b) Completely ignore or exclude him or her from their group of friends or leave him or her out of things on purpose;

c) Hit, kick, push, shove around, or lock him or her inside a room;

d) Tell lies or spread false rumors about him or her or send mean notes and try to make other students dislike him or her;

e) And other hurtful things like that Carvalho [44].

This definition of bullying is generally acknowledged by researchers, and accords with Olweus’s definition Olweus [45]. Thus, questionnaires introduce the definition of cyberbullying. However, definitions of cyberbullying can differ, since there are divergent opinions among researchers. To follow, there is an example of a definition of cyberbullying from a well-known investigation into the subject which aimed to explore its forms, awareness, and impact, and the relationship between age and gender in cases of cyberbullying:

Today we would like to look at a special kind of bullying: Cyberbullying.

This includes bullying

a) Through text messaging

b) Through pictures/photos or video clips

c) Through phone calls (nasty, silent, etc.)

d) Through emails

e) In chat rooms

f) Through instant messaging

g) Through websites Smith et al. [44].

Even in the questionnaire’s premise, students are invited to keep in mind that bullying is when the above mean things happen repeatedly, and it is difficult for the student being bullied to defend him or herself. In fact, it is crucial that students understand that one is being bullied when they are teased repeatedly in a mean and hurtful way, but not bullied when the teasing is done in a friendly and playful way. Also, it is not bullying when two students of about equal strength or power argue or fight. We note that a circumscribed definition of bullying and cyberbullying is a necessary condition in a scientific survey. Nevertheless, it is not necessary to embark on a scientific discussion regarding the definition of cyberbullying when one would like to acquire information in the school district before planning a no-cyberbullying program. One needs more general information about students’ habits and their family context: the use of the internet and mobile devises, the hours spent online, the presence of violent conduct within their family context, their involvement in harmful incidents, the perceived level of hostility on the part of class-mates, their confidence in regards to new technologies and their assessment of their ability to use them, the awareness of cyber risks, the importance attributed to having an online profile, the importance of virtual relationships, and so on.

Combating cyberbullying is impossible if one doesn’t know the context where the cyberbullying takes place. The internet is a hugely vast world, difficult to probe, rich with dissimulations, full of useful but also evil things, that is continuously changing. One can observe that when young people are together in face-to-face meetings and talks, they continue using their mobiles and smart phones, simultaneously communicating with mates who are present, with others who are in distant places, and with virtual friends who they know only through the internet. An effort must be made to understand the world of young people and to deal with the presence of virtual reality8 in their life, recognizing their concerns and the significance of their online reputation. Moreover, victimization can begin at school and then extend into their home and community through the use of technology, but it is also possible that victimization via computers and mobiles can lead to face-toface victimization. The most troubled ones are those individuals who are simultaneously both bully and victim. This implies the need for new strategies of prevention and intervention. There are researchers in the psychological and psychiatric fields who argue that both cyberbullying and cyber-victimization are associated with psychiatric and psychosomatic problems, and the most troubled individuals are those who are both cyberbullies and cyber-victims Sourander et al. [11].

School staff should take account of this topical situation. An alarming, murderous, episode which happened in Italy on December 26th 2013 demonstrates the topicality of close ties between real and virtual life that is not only confined to young people. Creating a fake profile on Face book, 42 years old woman provoked the mad jealousy of her partner, who went on to brutally kill her9

Educate that all Forms of Bullying are Unacceptable

The most important educational tip from Hinduja & Patchin is that one ought to “teach students that all forms of bullying are unacceptable and that cyberbullying behaviors are potentially subject to discipline”. This is also one of the four key principles of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program Olweus [45] that calls for “firm limits on unacceptable behavior”. In accordance with another Olweus key principle that calls for “warmth, positive interest, and involvement from adults”, Hinduja & Patchin suggest that educators have a conversation with students about what “substantial disruption” means. Students need to know that even a behavior that occurs miles away from the school could be subject to school sanctions if it disrupts the school environment. This tip is linked to another tip which we have included in the class of technical support. The author’s suggestion is to “create a comprehensive formal contract” specific to cyberbullying in the school’s policy manual, or to introduce clauses within the formal “honor code” which identify cyberbullying as an example of inappropriate behavior. Following this tip, many schools in the USA have adopted a zero-tolerance policy against cyberbullying. We concur that teaching students about the inappropriateness of cyberbullying is a primary action in combating it.

We agree that a school must openly declare that cyberbullying is not an acceptable and admissible behavior, and rules about this phenomenon must be implemented. We suggest the need to define these rules, which should be periodically reviewed, in a process that involves school staff, parents and students’ representatives. The definition and updating of no-cyberbullying rules presents an opportunity to illustrate the consequences of acts of cyberbullying, also from a legal point of view. However, teachers and educators must keep in mind that current regulations have a low impact in terms of combatting and punishing cyberbullying. Social networking sites such as MySpace and Facebook allow any users older than fourteen to become members of their sites once they register. Registration requires users to submit personal information, choose a password, and agree to the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy (TOS) bychecking a box or carrying out other operations required to access the service. However, in regards to TOS, the case of Lori Drew is an instructive and illuminating one10. This case has been widely covered in the international media, becoming an iconic tale of cyberbullying. Lori Drew helped her daughter to create a false profile on MySpace.com in order to contact a class-mate and neighbor of hers, thirteen-year-old Megan Meier [46].

The profile falsely purported to be that of an attractive sixteenyear- old boy named Josh Evans. Lori Drew declared that the purpose of the fake profile was to obtain confidential information as to what Meier was saying about her daughter. A month later Meier received an instant message from “Evans” saying that he no longer liked her and that “the world would be a better place without her in it.” That same day, Meier committed suicide. Lori Drew was accused of breaking federal laws, since she orchestrated a MySpace hoax that led to her neighbor’s child’s death. The government’s view of the Drew case was that the creation of the “Josh Evans” profile had violated the TOS of MySpace.com, and that this violation of the TOS rendered the access to MySpace’s servers as either lacking authorization or exceeding authorization. The first guilty verdict was overturned by the federal judge handling the case. The judge accepted the argument of the defense. As a matter of statutory construction, the TOS did not govern authorization: in fact, MySpace had given authorization to access its computers by creating the Josh Evans account and allowing the group to send and receive messages using it Kerr [47]. At trial, the vice president of customer care at MySpace testified that the sheer volume of 400 million MySpace accounts made it virtually impossible to determine which accounts were in violation of their TOS.

Foot Note:8http://bari.repubblica.it/cronaca/2013/12/28/news/cadavere_di_donna_nelle_campagne_l_amante_confessa_sono_stato_io-74647487/?ref=HREC1-8.

9United States v. Drew, 2008 WL 2078622.

10In 2009, Linda T Sanchez, a Member of Congress from California, introduced the Megan Meier Cyberbullying Prevention Act 51. The proposed statute sought to criminalize “any communication, with the intent to coerce, intimidate, harass, or cause substantial emotional distress to a person, using electronic means to support severe, repeated, and hostile behavior.” The Megan Meier act was not approved by congress in 2009, and there have been no new acts proposed in congress since.

As Meredith observes: Practically speaking, the repercussions for violating the My Space TOS involve My Space contacting law enforcement directly only in rare circumstances. More likely, MySpace would simply warn the violative users that their actions might warrant involvement of law enforcement or the removal of the offensive profile from the MySpace site Meredith [48]. The other Hinduja, Patchin tips for a no-cyberbullying educational program are referred to a crucial aspect: the participation of all involved subjects in its development. They suggest using peer mentoring to promote positive online interactions, for example organizing lessons by older students who informally teach and share learning experiences with younger students. Another tip is to cultivate a positive school climate. They argue that it is crucial to establish and maintain a climate of respect and integrity where violations result in informal or formal sanctions. They also recommend utilizing specially-created cyberbullying curricula, or general information sessions such as assemblies and in-class discussions to raise awareness among youth. Finally, they underline the importance of inviting specialists to come to talk to staff and students, sending information out to parents, and organizing educational events involving parents, relatives, and any other relevant adult. Specialists and educators should emphasize the advantages offered by new technologies. They can be used not only to support learning activities, but also to enhance positive social relationships. Moreover, social networking and virtual relationships are useful for people who experience difficulties in engaging in face-to-face social relationships, and online anonymity may lower the barriers to meeting new friends. Social networking sites help a person to reach large audiences and talk about what is going on in their lives and how they feel Heirman & Walrave [49]. Social networking can help individuals to find others who share mainstream but specific interests or those who share culturally devalued identity aspects that could be quite difficult in one’s everyday social world Mc Kenna [50].

Also, drawing from what Meredith [48] writes, we would add a consideration to the above suggestions concerning the over-criminalization of cyberbullying. Indeed, we agree with her observation that one ought to avoid over-criminalization, and carefully act only in case of criminal activities. In this regard, Meredith reports about the failure to distinguish acts of cyberbullying perpetrated by minors from those perpetrated by adults, and she underlines the difficulty of regulating unpleasant speech that doesn’t reach the level of a true threat. She cites some cases where the law considered cyberbullying to be a juvenile issue and as such required the schools to create policy to prevent it. This represents a shifting of the blame, which charges the schools with extra responsibility. In this perspective, efforts should be concentrated on increasing the education for internet safety. Educators should be empowered with the proper tools to inform students and parents about how to use technology in a wise way. It is crucial, here, to provide information that increases awareness about the risks of cyberspace. In the first place, children should be taught to utilize the positive aspects of the internet without becoming victims of the evil hidden inside it.

However, attempts at combating cyberbullying through legislation should also be pursued. The first.com legislation related to the prevention of cyberbullying was introduced in April 2009, but, at the moment, only a few states in the United States have enacted anti-bullying legislation, while some states have anti-bullying policies in place, pending legislation, or discussions about the need for or status of their policies or laws. However, cyberbullying legislation is not an easy issue, it is sometimes difficult to extricate and distinguish what really constitutes online harassment, defamation, and hateful speech at a legal level. Although these factors represent a significant problem, there are few legal remedies for victims Marwick [51]. Accordingly, one should tackle this issue whilst keeping the considerations of Linda Sanchez in mind that are cited by Meredith [51]11 I want the law to be able to distinguish between an annoying chain email, a righteously angry political blog post, or a miffed text to an ex-boy friend all of which are and should remain legal; and serious, repeated, and hostile communications made with the intent to harm. Sanchez alludes to a legislative effort, but her aim should be extended to the possibility of preventing cyberbullying through new and sophisticated software tools. Software producers should provide solutions for the safe use of their products. This said, the role of the media should also not be overlooked.

Foot Note:11http://inchieste.repubblica.it/it/repubblica/repit/2013/06/03/news/quando_i_social_network_uccidono_gli_adolescenti_vittima_di_ cyberbullismo-60257903/

The Media Role: Is Cyberbullying an Exaggerated Threat?

In an article which reviews and discusses the current state of the art of international research on cyberbullying Cassidy [52] observe that, increasingly, cyberbullying is mentioned alongside traditional bullying as an exploding phenomenon with which researchers and practitioners must contend. Researchers who share the opinion that cyberbullying is increasing are very numerous Ybarra [5]; Campbell [53]; Cowie [54]; Smith & Slonje [55]; Bulut [56]; Demaray [57]; Hatzchristou [58]; Kowalski et al. [36]; Kowalski [59]; Soto [60]; von Mare´es [61]. International quantitative research studies reveal a significant magnitude of cyberbullying among pupils, but we cannot help but observe that specific results vary considerably across cultures and across studies David-Ferdon [62]; Smith et al. [30]. This can be partially explained by the disparate definitions and methods utilized by studies until now. Therefore, it seems problematic to compare prevalence rates. In Li’s Canadian study, it was found that 25% of pupils have never been a victim of cyberbullying, whilst 17% have cyberbullied others Li 2006. But data is not so definite. In a less recent survey carried out in the USA, Ybarra [5] challenged the dichotomized perception of cyberbullies/ online-victims, and compared the prevalence rates among four groups. In this sample, 4% of the young people had been the target of online aggression, 12% were online aggressors, 3% were both aggressors and targets of online bullying, whilst 81% were not implicated in online bullying in any way. Some researchers Cassidy [52]; Kowalski et al. [36]; Rivers [63] have found an increased rate of prevalence over the past five years.

There are, however, those who don’t agree with the notion that there has been a deluge of cyberbullying. Some researchers Olweus [64,65]; Li et al. [66]; Hinduja [31] claim that the rate of cyberbullying has not increased at all since the phenomena first emerged as a problem in the middle of the last decade. Nevertheless, one fact is certain: the last few years has seen a growing interest in cyberbullying in the media. As a result, the media has stimulated an awareness of the issue on the part of public authorities and also of ordinary citizens Dooley et al. [18]; Patchin 2011; Li [66].

Recently, newspapers and television programs are beginning to deal with cyberbullying, especially when an extreme case occurs, such as the suicide of a targeted adolescent. In general, the media report about victims’ parents who angrily accuse classmates, school authorities, and the government since, in their opinion, they didn’t do anything to combat and stop the cyberbullies. On the other hand, classmates and school authorities always claim that they were unaware of anything wrong, whilst the police complain that there are huge amounts of grossly offensive, indecent, and obscene comments made every day on social media. The police object that they cannot analyze all the malicious/aggressive content, and claim that many of this content don’t meet the threshold that would justify their involvement under current legislation. However, all the above-mentioned subjects confirm that social network providers should do more by taking countermeasures and controlling and filtering their site’s content.

There is no doubt that newspapers and the media in general interpret the popular disquiet around cyberbullying and present it as an alarming and increasing phenomenon. In this regard, one must keep in mind that the media often exaggerate, as in the following example. “Quando i social network uccidono: adolescenti vittime di cyberbullismo [When social networks kill: adolescent victims of cyberbullying]” was an online article, published on June 3rd 2013, by Repubblica, a widely-read Italian newspaper. The same article was re-published on August 12th of the same year, after fourteen years old boy who was presumed to be gay committed suicide. However, after some days of inflamed articles and recriminations against homophobia, the police excluded the cyberbullying hypothesis as being the cause of his suicide. It shouldn’t surprise anyone if, immediately following the incident, gay, civil rights, and left-wing associations invoked a new, stricter law to combat homophobia and cyberbullying. Nevertheless, we have illustrated the fact that increasing legislation is not an easy matter, since a universally agreed definition of cyberbullying does not exist. A question remains open, however, regarding the media and cyberbullying. Does the increase of cyberspace risks correspond to reality, or is this an over-inflated projection of popular fear? To this end, it is useful here to report on Olweus’s considerations regarding cyberbullying.

Olweus, the pioneering researcher in the field of bullying prevention and the creator of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program, observed that cyberbullying has been studied ‘‘in isolation’’, that is, outside a general context of traditional bullying, and this study often takes place without a general student-friendly definition of what is meant by bullying. For Olweus, a student is being bullied when another student, or several other students:

a) Say mean and hurtful things or make fun of him or her or call him or her mean and hurtful names;

b) Completely ignore or exclude him or her from their group of friends or leave him or her out of things on purpose;

c) Hit, kick, push, shove around, or lock him or her inside a room;

d) Tell lies or spread false rumors about him or her or send mean notes and try to make other students dislike him/ her;

e) Inflict other hurtful things like that.

These characterizing traits of bullying are the same as those reported in the previously-mentioned example questionnaire on cyberbullying devised by Smith et al. [44]. Olweus underlines that the general picture created in the media -and also by researchers and authors of books on cyberbullying- is that cyberbullying is very frequent, that it has increased dramatically over time, and that this new form of bullying has created many new victims and perpetrators. More precisely, he argues that claims about cyberbullying being made in the media and elsewhere are often greatly exaggerated and, by and large, have very little scientific support. Furthermore, he notes that such claims may have some unfortunate consequences, confirming that his arguments are based on empirical analyses of several large-scale studies. He concludes that a presumably quite effective measure that an individual school or community can take to counteract and prevent cyberbullying is to invest time and technical competence in thoroughly disclosing a few identified cases of cyberbullying, and then to clearly and openly but anonymously communicate the results to the students.

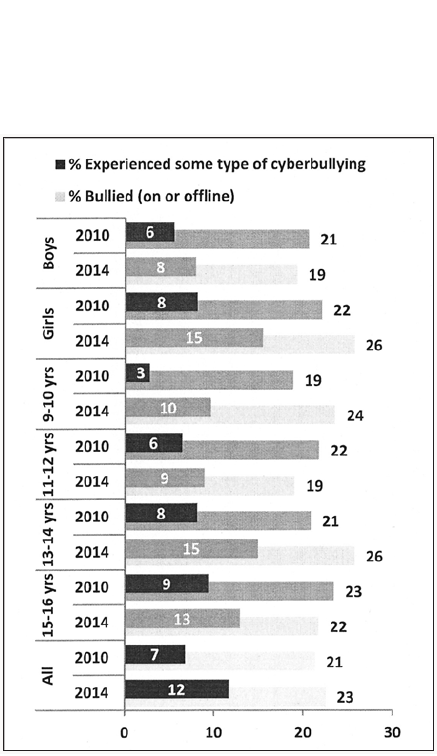

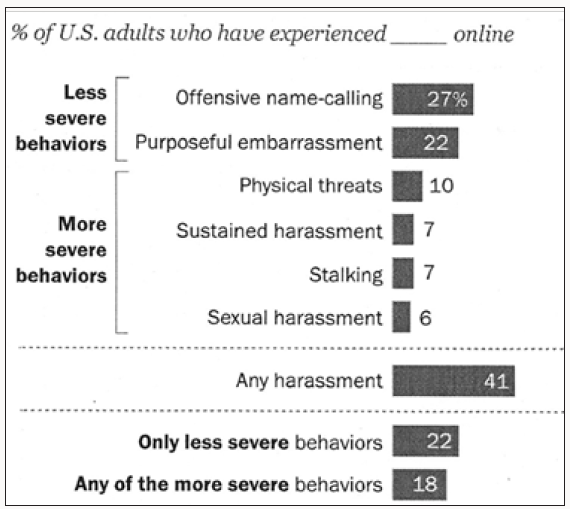

In our opinion, Olweus’s considerations only confirm the novelty, the multifarious nature, of cyberbullying and the difficulties we face in embracing all its facets. However, we are presented with an uncomfortable fact: nobody who is sane of mind would put a gun in the hand of a child, but new technology can be far more powerful and lethal than any hand-held weapon. Indeed, the Ditch the Label Annual Cyberbullying Survey 201312 conducted in the UK on a sample of 10,008 young people shows that 69% of young people in the UK experience bullying before the age of 18, and that over 2.5 million youths are bullied each year and 550,547 are bullied every single day. A survey of 23,420 children and young people across Europe Livingstone [67] found that 5% of respondents were being cyberbullied more than once a week, 4% once or twice a month, and 10% less often; the vast majority were never cyberbullied. A recent research by the Pew Research Center (Duggan, 2017) reveals that roughly four-in-ten Americans have experienced some form of online harassment (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1: % of U.S. adults who have experienced online harassment (source: Survey conducted Jan. 9-23 2017by the Pew Research Center).

Figure 2: % of U.S. adults who say they have experienced each type of online harassment in 2014 vs. 2017 (source: Survey conducted Jan. 9-23 2017by the Pew Research Center).

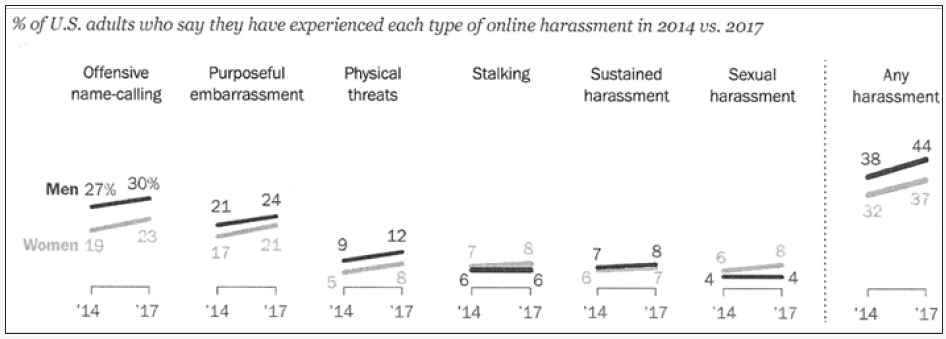

The data clearly indicates the increase in online harassment. From the UK Kids Online comparison of the data from two surveys conducted in 2010 and 2014, it emerges that cyberbullying is widespread in European countries, especially among girls and the youngest age group cyberbullying and bullying experiences source: EU Kids Online, 201413 (Figure 3).

Foot Note:12http://www.ditchthelabel.org.

13http://netchildrengomobile.eu/reports.

Nevertheless, the responsibility of the media in exaggerating the extent of cyberbullying is evident, since they tend to consider as cyberbullying every incident that is in any way related to social networks. This is the case of Tiziana Cantone, who committed suicide after some of her amateur porno-videos were posted on WhatsApp and Facebook14. Although this incident was related to neither cyberbullying nor revenge porn but was instead a case of privacy violation, the Italian parliament exploited it to initiate a campaign against cyberbullying, and went on to approve a special law against it.

Cyberbullying and New Media Knowledge

The majority of teens are online, particularly through mobile connections. The nature of internet use by teens has transformed dramatically over time - from stationary connections tied to desktops in the home to always-on connections that move with them throughout the day. In many ways, teens represent the leading edge of mobile connectivity, and the patterns of their technology use often signal future changes in the adult population. Teens are just as likely to have a cell phone as they are to have a desktop or laptop computer.

Teachers, educators and parents are generally less skilled than the young in using new technologies. This represents a serious problem that leads to inadequate supervision at school and at home, and limits cyberbullying prevention Popovic´-C´ [68]. Moreover, although younger educators are more familiar with technology and are concerned about cyberbullying, they are not able to translate their knowledge into policies or programs within the school. In general, teachers are more likely to focus on preventing face-toface bullying than cyberbullying. However, the lack of knowledge of technology is not the only obstacle in preventing cyberbullying. The main problem is that cyberbullying requires a multidisciplinary approach in both policy development and teacher training. Cyber-themed school assemblies and curriculum lessons can be useful for spreading knowledge among school staff and recovering the technological gap (Paul, Smith, & Blumberg, 2010), but the professional foundations of school staff should also be enriched by other notions related to the psychological, pedagogical, and social themes found in cyberbullying, such as reviewing traditional concepts of self-esteem, peer relationships, empathy, communication, power imbalance, etc.

In regards to technology, we need to have a thorough knowledge of the various media used for online bullying. Some authors classify cyberbullying by the types of medium, distinguishing cyberbullying via SMS, via e-mail, via instant messaging, and soon Patchin [69]; Smith et al. [70]; Limber [71]; Ortega [72] recommend the categorization of cyberbullying by type of action, as with the taxonomy by Willard (2007), who defined eight subcategories of cyberbullying. Willard herself acknowledges that some of the phenomena she lists should rather be called “online social cruelty”. The classic forms of cyberbullying are: Harassment that can be defined as repetitiously sending insulting or threatening messages to another person by e-mail, SMS, instant messaging, or in chatrooms; Denigration, which is the spreading of rumors via electronic communication devices. Unlike gossip in real life, via the internet information can be sent to thousands of people within seconds; Outing & trickery is similar: a message revealing personal information, which the victim sent to someone in confidence, is forwarded to other people in order to compromise the victim; Exclusion is equivalent to exclusion in real life, and means withholding the opportunity to take part in social activities. In an online context, this could mean excluding someone from multiplayer games, chats, or platforms. Technology affects the relationship between victim and perpetrator, creating new types of bullying:

a) Bully knows victim and victim knows bully;

b) Bully doesn’t know victim and victim doesn’t know bully;

c) Bully knows victim but victim doesn’t know bully.

In cyberspace, bullies can choose unknown targets to harass by sifting through social networking profiles, but there are frequent cases where an anonymous post in a blog provokes aggressiveness against its author. On the internet, episodes which mutate into virtual group violence are not unusual: people participating in a blog begin to insult the author of a post, but later they look for him/ her on the Web continuing to offend and threaten the victim. The level of aggression in some political blogs is often also very high Grillo’s blog in Italy15.

Foot Note:14http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/tiziana-cantone-sex-tape-revenge-porn-suicide-death-italy-online-privacy-laws-campaignoverhaul- a7310956.

Harmful use of new media is not only specific to young people and circumscribed to the private or political sphere; however, it can also affect public institutions. This is the case of an Italian public university which utilized Facebook facilities for the purpose of giving students a place to post their questions, exchanging comments/complaints, and vent their protest, or make a compliment. Students are free to post their comments without any filter, and recently, in 2014, a big problem arose when a student posted unfair accusations, offending an employee. It seems incredible, but for more than 20 days the site manager continued to exchange messages with the student, expressing solidarity, before alerting the unaware colleague about the situation. The manager also asked the student to forward on the emails received from the employee. When the student sent them, apologizing for the trouble caused, the manager’s response was: “You don’t have to apologize: we should do it”. The messages were visible to a community of about 6,000 members, including many people coming from a University environment. One might think that the incident would inspire Sutton to enrich his famous book, the no assole rule Sutton [73], but it is also emblematic of the risks of uncontrolled or personal use of social media in a public environment. Right now, the internet is an uncontrollable and unregulated world, and technology offers a much wider audience for backstabbing and treachery than there was in the past.

Technical Support

Hinduja and Patchin’s ten tips include some suggestions which we have defined as technical support. For instance, they suggest implementing blocking/filtering software on computer networks to prevent access to certain Web sites and software. These preventive measures are necessary, but they are not definitive. In fact, there are many commercial, open source, and freeware software programs that provide functions for implementing parental control. Many of these enable parents to control children’s internet activities, restrict access to certain websites, and limit the length of time surfing. Nevertheless, parental controls can be bypassed; one can use a different computer where no filters are configured, while the proliferation of mobile technologies offers new opportunities for accessing the internet. Hinduja & Patchin also underline the importance of consulting school attorneys before cyberbullying incidents occur, in order to find out what actions can or must be taken in various situations. It is certain that knowledge of the law can help to tackle cyberbullying incidents. It is especially useful for avoiding conflict and long and expensive lawsuits. At the moment, we are skeptical about the effectiveness of the law in preventing cyberbullying. The debate on this point demonstrates the wide divergence of views between insiders and experts. A delicate underlying issue concerns internet censorship. Are cyberbullying laws a form of censorship? Edward Snowden’s revelations regarding.com global surveillance operations are feeding the debate on this issue. However, some practical ideas about this issue are contained in a book by C Zuchora-Walske [74]. The author holds that the internet censoring debate should be tackled considering that is made up of several smaller debates and involves many sticky questions:

a) What is the best way to keep children safe online?

b) Should we use laws to protect children from inappropriate online contents?

c) Is a combination of educational and parental involvement a better strategy?

d) It is possible - or even desirable – to demand civility (polite behavior) on the internet?

e) Does online civility help to preserve a peaceful society?

f) Should internet users adhere to traditional values?

Furthermore, in respect to technical support, we note that effective technological assistance in combating cyberbullying could come from machine learning applications Moore [75]. Automatic text analysis of social networking contents is a new field of research, and the results so far obtained encourage insiders to continue in this direction Dinakar [76]; Berrueco [77]; Reynolds [78]; Kontostathis [79]. In this regard, 179 experts on cyberbullying were contacted and asked three open-ended questions relating to the desirability of automatic monitoring, of whom 50 (28%) responded Van Royen [80]. Most of these experts favored automatic monitoring, but specified clear conditions under which such systems should be implemented, including effective follow-up strategies, protecting the adolescents’ privacy, and safeguarding their self-reliance. Finally, machine learning programs can analyze posts and, through sophisticated algorithms, can identify harmful and risky content. Multilayer programs have been developed that are based on the analysis of messages. The basic layer extracts swear words or hateful words using a lexicology of bad words, e.g. slut, shit, ugly, hate, and so on. Other layers identify expressions that indicate anger and aggression, for example by taking into account how many letters are in CAPS and how often punctuation marks are used, such as “!!!” or “???”. Other hints of emotion and hostility can be detected by analyzing errors and the use of special symbols and emoticons, as well as by checking the reputation of the authors of messages, for example if they have previously demonstrated aggressive attitudes. However, to be effective, these programs should also be able to classify certain expressions as dangerous, such as “the world will be better without you” that became famous after the sad case of Megan Mayer.

Foot Note:15Beppe Grillo is an Italian comedian and politician. He launched Italy’s Five Star Movement, which recently won 109 seats in the country’s lower chamber of deputies, as well as 54 seats in the senate. His blog is characterized by verbal violence and boorishness.

Prevention Strategies

Much of the advice about preventing cyberbullying concerns training children and their parents in e-safety and implementing technological tools to counteract the cyberbullies’ behavior, such as blocking bullying behavior online or creating panic buttons for cyber victims to use when they feel under threat. Prevention through education is a strategy largely agreed on by researchers and practitioners alike. Preventing children from using the internet and smartphones is not an effective practice, as the following case demonstrates. To avoid acts of online bullying, the parents of a child, who we will refer to as E., prevented her from surfing on the internet in their absence, and only gave her the possibility to use an old mobile phone that was not equipped with multimedia features and an internet connection in special cases. However, when E. was thirteen she became a victim of cyberbullying. How could this happen? Classmates showed her that there were messages on Facebook denigrating and ridiculing her. These messages were posted by other mates that, in front of her, acted in a kind and gentle way. The consequence was that E. was doubly upset: she could not understand why her friends denigrated her and, at the same time, she was not able to respond to them. Indeed, she could not connect to the internet and, as a consequence, was at the mercy of friends to see the hurtful messages concerning her. This created serious stress problems for E., and her parents were forced to move her to a different school.

All insiders agree with the opinion that criminalization is not the right answer to combating cyberbullying, since its negative consequences outweigh the possible positive effects. In contrast, education in internet safety has proven effective, and empowering educators with theoretical and practical tools is an extremely valid key. Peer education programs and peer support models are also deemed useful. These are based on the assumption that peers learn from one another, and have significant influence on each other. Conduct and behavior are most likely to change when liked and trusted group members take the lead in changing the situation Naylor [81]; Turner [82]; Maticka [83].

There are several curriculum-based programs available to educators that strive to help in preventing cyberbullying Snakenborg [84]. Some examples of cyberbullying combating programs are also available on the internet, while prevention programs focused at a school level appear to be most efficient Couvillon [85]. The current bullying and cyberbullying preventing strategies share a school approach, and many of them are conceived in a way that involves pupils, educators, and parents Perren et al. [86]; Mc Guckin et al. [87]. Various prevention programs are based on research by Olweus [45]; Spears [39]; Mustacchi [88]; Katzer [89]; Couvillon [85]. Some authors have underlined that it is essential that any cyberbullying prevention program include extensive training for educators Ttofi [90], as well as education on the use of the internet technologies Brewer [91]. Four major coping strategies have been identified Riebel [9]:

a) Social coping: seeking help from family, friends, teachers, peer supporters;

b) Aggressive coping: retaliation, physical attacks, verbal threats;

c) Helpless coping: hopelessness, passive reactions, such as avoidance; displays of emotion;

d) Cognitive coping: responding assertively, using reason; analyzing the bullying episode and the bully’s behavior.

One program that is very interesting is the internet safety educational experiment developed by Mustacchi at Pierre Van Corlandt Middle School in New York, which was based on a peer and collaborative learning approach Mustacchi [88]. The author based her education program on the core evidence that adolescents have continuous peer connections. Accordingly, she first provided eighth graders with training on netiquette (proper internet behavior). Then, when eighth graders were well grounded in netiquette, they were engaged to teach to sixth grades, preparing skits on cyberbullying topics that were presented in an assembly setting, with a group of adults also present that included counsellors, the school psychologist, and law enforcement officers, who were present to answer questions. Mustacchi’s educational program received a strong positive response from participants.

The KiVa anti-bullying program presents many analogies with Mustacchi’s educational program. KiVa (acronym for Klusaamista Vastaan, “against bullying”) is a Finnish program that targets traditional bullying. Researchers claim that this program significantly reduces (by about 50%) incidents of traditional bullying Salmivalli [92]; Kärnä [93]; Voeten [94]; Haataja [95] as well as cyberbullying Williford [96]. The KiVa program is based on a whole school approach that includes classroom teaching, training in reporting bullying incidents, and monitoring the implementation of the program. The KiVa program distinguishes separate curricula for primary students, middle students, and high school students. The program is designed to strengthen empathy, and is run over a fourmonth period. It requires a whole school effort: students see video clips and play online games relating to both traditional bullying and cyberbullying, while parents are taught about online monitoring applications. Teachers and administrators are also trained on the dynamics of bullying and on how to manage the bullying. Administrators participate in the training as well. A prerequisite to run KiVa is the provision of training to school teaching and administrative staff by an expert KiVa trainer. Currently the KiVa program has licensed partners in about 15 countries16.

Foot Note:16http://www.kivaprogram.net/around-the-world.

However, designing preventative strategies is not at all simple. Firstly, an effective prevention program should be grounded on the knowledge of new media and the understanding of their use by the different typologies of users, especially adolescents and young people. This implies that trainers have to be skilled in the new media, and should show their mastery to learners, otherwise their image as experts and authorities could be discredited.

Another important aspect concerns the issue of virtual identity and its reciprocal effects on physical identity. It has been observed that at the heart of the explosion in online communication is the desire to construct a valued representation of oneself which affirms and is affirmed by one’s peers (Livingstone & Brake, 2010). Accordingly, by exploiting new media, people can reconstitute and experiment with their identity in the online domain. If identities are constituted through interaction with others, what is the consequence on identity constitution if the interaction is a mix of physical and virtual interactions? And what ifvirtual interactions are not only with real people but also with electronic programs and with virtual fake profiles constructed by physical persons?

In this regard, what Leanhart17 wrote in 2008 regarding Facebook and offline identities still seemstopical:18 In the offline world, we don’t present ourselves in the same way to all people in our lives - we show different sides of ourselves to our mothers, our friends, our employers. And even in the age of fine-grained privacy tools, those tools do not eliminate the complexity of figuring out how to best present oneself in a multi-use public space, particularly for those who have personal, professional and family contacts on these sites.

Finally, cultural aspects should not be undervalued. They can play a role that may not be secondary if one adopts prevention programs that have been created and experimented in other countries. The cultural sensitivity of cyberbullying is an issue that has been largely unexplored by researchers. Some research studies try to test the relation between culture and cyberbullying by comparing questionnaire results submitted in different countries, for example in the United States and Japan Barlett et al. [97]. Indeed, the new cultural attitudes about new media open an intriguing question: is cyberbullying really an alarming issue across various age groups regardless of cultural background Mura [98]? Does cyberbullying depend only on the spread of new technologies or can some other factors, such as culture and historical heritage, influence it or at least influence its perception? In this regard, a research study conducted on teenagers in Latvia and Russia Boronenko [99] seems to show that cyberbullying is indeed culturally influenced, and is in line with the following observation:

Important considerations to keep in mind when comparing studies are cultural similarities and differences in both the prevalence of research on the topic of cyberbullying and the prevalence of cyberbullying itself within a particular culture Kowalski et al. [36]. Nevertheless, investigating cultural influences that affect cyberbullying presents many methodological problems. Analysis can be expensive and take a long time. Questionnaires should be integrated with other forms of data gathering, such as structured interviews, direct observation, and web analysis. The previously mentioned comparative research on cyberbullying in the USA and Japan and the research on cyberbullying in Russia and Latvia have used different methodological approaches, in the first a classic quantitative approach, while in the second a mix of socio-anthropological and qualitative-quantitative approaches. It is interesting that, despite the differences, the two studies share a similar hypothesis that cyberbullying is related to how individuals perceive, comprehend, and interpret the world around them (Individualism and Uncertainty Avoidance19 in the Latvia-Russia research, independent self-construal in the USA-Japan one).

Conclusion

Cyberbullying is an evil phenomenon that represents a serious form of misbehavior amongst young people, and its spread among young adolescents is alarming Kowalski [100]. For this reason, antibullying actions should be carried out also for preschool children and children in the first years of primary education. Freeman [101] describes how to identify bullying situations and defense strategies for preschool children.

Indeed, there is some evidence regarding cyberbullying that should be carefully considered. Within the last decade an impressive expansion of social media technologies has occurred. Over 65% of young people aged 11-16 now have a profile on a social networking site, and information exposure is more and more diffused among young people20. Information exposure is a seemingly bizarre phenomenon whereby individuals freely and deliberately disseminate confidential or personal damaging information (including incriminating facts) to the widest possible audience, apparently without any concern for the consequences. It is well known that adolescents have a tendency to feel constantly watched or “on stage” (“imaginary audience”), but information exposure is not just a phenomenon affecting adolescence. Speaking about Facebook, Leanhart’s observation 2008 still seems highly topical): 21 and now, Facebook is adding yet another layer of complexity on top of this, yielding a new round of personal behavioral scrutiny: is it OK for my coworker or professional colleague to know that I was watching a video yesterday? Or that I shopped at the Discovery Kids website? Do I want them to know that about me? And what about my child who uses these services?

Foot Note:1717Amanda Lenhart is a senior research specialist at the Pew Internet & American Life Project who resides in Washington DC. She has published numerous articles and research reports, many of which focus on teenagers and their interactions with the internet and other new media technologies.

1818http://www.self.gutenberg.org/articles/Amanda_Lenhart.

1919The uncertainty-avoidance dimension expresses the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity Hofstede [102].

20http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015.

Finally, there has been a notable rise in the number of gossip sites, which, in essence, are websites where individuals strive against each other to produce the most tantalizing snippets of gossip. The sites “rate” gossip based on the number of people who click on (and presumably read) the contents. In such a context that is hugely complex and fluid at the same time, affected by the fast evolution of technology and consumerism, what are the best strategies for the prevention of cyberbullying? In this article, some questions regarding the best strategies for combating cyberbullying have been presented. Indeed, prevention activities should follow the progress of research, paying attention to both the current evolution of technology, and the emerging aspects and harmful effects of cyberbullying. Empirical research should be increased and common initiatives on implementing preventative measures initiated, testing their applicability and benchmarking their results. Above all, however, it is crucial to advocate the role of schools in this endeavor; otherwise one runs the risk of shutting the barn door when the horse has already bolted. Anti-bullying and suicide awareness programs should be experimented that encourage teenagers to turn to educators if they are bullied or they are contemplating suicide. Educators and parents have to be aware that depression is the third leading cause of illness and disability amongst adolescents, and suicide is the third leading cause of death in older adolescents (15-19 years)22. Accordingly, providing adolescents with psycho-social support in schools is a crucial issue, as well as building programs to reinforce the ties between adolescents and their families.

In a recent book Patching [103] suggested combating cruelty with kindness, and using positive peer education to persuade all teens to act with respect towards others. Other authors have suggested empathic responsiveness and the moral disengagement from and disapproval of cyberbullying adopting a social-ecological approach Cross [104]. We can conclude by observing that cyberbullying prevention needs continuous and well-structured activities that should involve students, educators, and families. Conferences and lectures are important but don’t represent a solution. Education programs should be defined and run taking into account the evolution of technologies and social changes. We should be aware that the digital revolution has profoundly changed interpersonal relationships, and that we need new conceptual tools to understand how to manage the threats hidden in cyberspace. If we want to help young people to prevent these threats we have to understand their world and how they use the technologies of today [105-112].

Foot Note:21http://www.pewinternet.org/2008/12/02/facebook-connect-and-a-failure-to-understand-online-identity-management/; last accessed 7.20.2017.

22http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs345/en/; last accessed 7.20.2017

References

- Thomas HJ, Connor JP, Scott JG (2015) Integrating traditional bullying and cyberbullying: challenges of definition and measurement in adolescents-a review. Educational Psychology Review 27(1): 135-152.

- Menesini E, Nocentini A, Palladino BE, Scheithauer H, Schultze K, et al. (2013) Cyberbullying through the new media: Findings from an international network. In: Smith PK, Steffgen G (Eds.), Cyberbullying through the new media: Findings from an international network. Psychology Press, UK.

- Marzano G (2015) Cyberbullying Prevention: Some Preventing Tips. In: Sahlin J (Eds.), Social Media and the Transformation of Interaction in Society. IGI: Global, pp. 133-157.

- Beran T, Li Q (2005) Cyber-harassment: A study of a new method for an old behavior. Journal of Educational Computing Research 32(3): 265-277.

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ (2004) Online aggressor/targets, aggressors, and targets: A comparison of associated youth characteristics. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 45(7): 1308-1316.

- Beran T, Li Q (2008) The relationship between cyberbullying and school bullying. Journal of Student Wellbeing 1(2): 16-33.

- Kowalski RM, Limber SP, Agatston PW (2008) Cyber bullying, Wiley- Blackwell, Malden, Massachusetts, USA.

- Del RR, Elipe P, Ortega-Ruiz R (2012) Bullying and cyberbullying: Overlapping and predictive value of the co-occurrence. Psicothema 24(4): 608-613.

- Riebel J, Jaeger RS, Fischer UC (2009) Cyberbullying in Germany–an exploration of prevalence, overlapping with real life bullying and coping strategies. Psychology Science Quarterly 51(3): 298-314.

- Perren S, Dooley J, Shaw T, Cross D (2010) Bullying in school and cyberspace: Associations with depressive symptoms in Swiss and Australian adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 4(28): 1-10.

- Sourander A, Brunstein KA, Ikonen M, Lindroos J, Luntamo T, et al. (2010) Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: A population-based study. Archives of General Psychiatry 67(7): 720.

- Smith PK, Cowie H, Olafsson R, Liefooghe A (2002) Definitions of bullying: a comparison of terms used and age and gender differences, in a fourteen-country international comparison. Child Dev 73(4): 1119-1133.

- Hinduja S, Patchin J (2006) Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: a preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 4(2): 148-169.

- Hinduja S, Patchin J (2007) Offline consequences of online victimization: school violence and delinquency. Journal of School Violence 6(3): 89-112.

- Hinduja S, Patchin J (2008) Cyberbullying: an exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behavior 29(2): 129-156.

- Ybarra M, Mitchell K, Wolak J, Finkelhor D (2006) Examining characteristics and associated distress related to Internet harassment findings from the second youth internet safety survey. Pediatrics 118(4): 69-77.

- Ybarra M, Mitchell K (2007) Prevalence and frequency of Internet harassment instigation: implications for adolescent health. J Adolesc Health 41(2): 89-95.

- Dooley JJ, Pyżalski J, Cross D (2009) Cyberbullying versus face-to-face bullying. J Psych 217(4): 182-188.

- Lenhart A (2010) Cyberbullying 2010: what the research tells.com. Youth Online Safety Working Group.

- Ortega Ruiz, Nunez JC (2012) Bullying and cyberbullying: research and intervention at school and social contexts. Psicothema 24(4): 603-607.

- Heirman W, Walrave M (2012) Predicting adolescent perpetration in cyberbullying: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Psicothema 24(4): 614-620.

- Wachs S, Wolf KD, Pan CH (2012) Cybergrooming: risk factors, coping strategies and associations with cyberbullying. Psicothema 24(4): 628-633.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23079362

- Palladino BE, Nocentini A, Menesini E (2012) Online and offline peer led models against bullying and cyberbullying. Psicothema 24(4): 634- 639.

- Paul S, Smith PK, Blumberg HH (2012) Investigating legal aspects of cyberbullying. Psicothema 24(4): 640-645.

- Vandebosch H, Van Cleemput K (2008) Defining cyberbullying: A qualitative research into the perceptions of youngsters. Cyber Psychology & Behavior 11(4): 499-503.

- Vandebosch H, Beirens L, D’Haese W, Wegge D, Pabian S (2012) Police actions with regard to cyberbullying: the belgian case. Psicothema 24(4): 646-652.

- Franco LR, Bellerín M, Borrego J, Díaz F, Molleda C (2012) Tolerance Towards Dating Violence in Adolescents. Psicothema 24(2): 236-242.

- Alipan A, Skues J, Theiler S, Wise L (2016) Defining cyberbullying: a multiple perspectives approach. Stud Health Technol Inform 219: 9-13.

- Kowalski RM, Limber SP (2007) Electronic bullying among middle school students. J Adolesc Health 41(S6): S22-S30.

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, et al. (2008) Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(4): 376-385.

- Hinduja S, Patchin JW (2012) Cyberbullying: Neither an epidemic nor a rarity. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 9: 539-543.

- Belsey B (2005) Cyberbullying: An emerging threat to the ‘always on’ generation.

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J (2011) Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. J Adolesc Health 48(2): 121-127.

- Law DM, Shapka JD, Hymel S, Olson BF, Waterhouse T (2012) The changing face of bullying: An empirical comparison between traditional and internet bullying and victimization. Computers in Human Behavior 28(1): 226-232.

- König A, Gollwitzer M, Steffgen G (2010) Cyberbullying as an act of revenge? Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling 20(02): 210- 224.

- Kowalski RM, Limber SP, Agatston PW (2012a) Cyberbullying: bullying in the digital age. 2nd edn. Wiley-Blackwell Company, Massachusetts, USA.

- Menesini E, Nocentini A, Palladino BE, Frisén A, Berne S, et al. (2012) Cyberbullying definition among adolescents: A comparison across six European countries. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 15(9): 455-463.

- Patchin JW, Hinduja S (2016) Bullying today: Bullet points and best practices. Corwin Press.

- Spears BA, Zeederberg M (2013) Emerging methodological strategies to address cyberbullying: Online social marketing and young people as co-researchers. In: Bauman S, Cross D, Walker JL (Eds.), Principles of cyberbullying research: Definitions, measures, and methodology, Routledge, New York, USA, pp. 166-179.

- Kochenderfer-Ladd B, Pelletier ME (2008) Teachers’ views and beliefs about bullying: Influences on classroom management strategies and students’ coping with peer victimization. J Sch Psychol 46(4): 431-453.

- Ryan T, Kariuki M, Yilmaz H (2011) A comparative analysis of cyberbullying perceptions of preservice educators: Canada and Turkey. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET 10(3): 1-12.

- Sahin M (2010) Teachers’ Perceptions of Bullying in High Schools: A Turkish Study. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 38(1): 127-142.

- Craig WM, Henderson K, Murphy, JG (2000) Prospective teachers’ attitudes toward bullying and victimization. School Psychology International 21(1): 5-21.

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Tippett N (2006) An investigation into cyberbullying, its forms, awareness and impact, and the relationship between age and gender in cyberbullying. DFES, London, UK, pp. 1-69.

- Olweus D (1993) Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Wiley-Blackwell, Massachusetts, USA.

- Olweus D (1999) Norway. In: Smith PK, Morita Y, Junger TJ, OlweusD, Catalano R, et al. (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: A cross-national perspective. Routledge, London, UK, pp. 28-48.

- Kerr OS (2009) Vagueness Challenges to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Minn L Rev 94: 1561-1587.

- Meredith JP (2010) Combating cyberbullying: emphasizing education over criminalization. Federal Communications Law Journal 63(1): 311-340.

- Heirman W, Walrave M (2008) Assessing concerns and issues about the mediation of technology in cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 2(2).

- Mc Guckin C, Perren S, Corcoran L, Cowie H, Dehue F, et al. (2014) Coping with cyberbullying: How can we prevent cyberbullying and how victims can cope with it. In: Smith PK, Steffgen G (Eds.), Cyberbullying through the new media: Findings from an international network. Psychology Press, New York, USA.

- Marwick AE, Miller RW (2014) Online harassment, defamation, and hateful speech: a primer of the legal landscape. Fordham Center on Law and Information Policy Report p. 1-75.

- Cassidy W, Faucher C, Jackson M (2013) Cyberbullying among youth: A comprehensive review of current international research and its implications and application to policy and practice. School Psychology International 34(6): 575-612.

- Campbell MA (2005) Cyber bullying: An old problem in a new guise? Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling 15(1): 68-76.

- Cowie H, Hutson N, Jennifer D, Myers CA (2008) Taking Stock of Violence in UK Schools Risk, Regulation and Responsibility. Education and Urban Society 40(4): 494-505.

- Paul S, Smith PK, Blumberg HH (2010) Addressing cyberbullying in school using the quality circle approach. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools 20(02): 157-168.

- Bulut S, Gündüz S (2012) Exploring violence in the context of Turkish culture and schools. In SR Jimerson, AB Nickerson, MJ Mayer, MJ Furlong (Eds.), Handbook of school violence and school safety: International research and practice (2nd edn.) New York, USA. pp. 165-174.

- Demaray MK, Malecki CK, Jenkins LD, Westermann LD (2012) Social support in the lives of students involved in aggressive and bullying behaviours. Handbook of school violence and school safety: International research and practice 57-67.

- Hatzchristou C, Polychroni F, Issari P, Yfanti T (2012) A synthetic approach for the study of aggression and violence in Greek schools. In Jimerson SR, Nickerson AB, Mayer MJ, Furlong MJ (Eds.), Handbook of school violence and school safety: International research and practice (2nd edn.), New York, USA.

- Kowalski RM, Morgan CA, Limber SP (2012b) Traditional bullying as a potential warning sign of cyberbullying. School Psychology International 33: 505-519.

- Soto CM, Campos JC, Morales LB (2012) Bullying in Peru: A code of silence. In: Jimerson S, Nickerson , Mayer MJ, Furlong MJ (Eds.), Handbook of school violence and school safety: international research and practice. Routledge, New York, USA.

- Von Mare´es N, Petermann F (2012) Cyberbullying: An increasing challenge for schools. School Psychology International 33(5): 467-476.

- David-Ferdon C, Hertz MF (2007) Electronic media, violence, and adolescents: An emerging public health problem. J Adolesc Health 41(6): S1-S5.

- Rivers I, Noret N (2010) ‘I h8 u’: Findings from a five-year study of text and email bullying. British Educational Research Journal 36(4): 643-671.