Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6695

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6695)

First Contact Colonial Era Native American Tribes Become Visible Through the Collection of Health Status Data Volume 3 - Issue 4

John Lowe1*, Eugenia Millender2, Casey Xavier Hall2, Rose Wimbish-Tompkins3*, Dennis Coker4 and Melessa Kelley1

- 1University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing, Austin, Texas, USA

- 2Florida State University College of Nursing, Tallahassee, Florida, USA

- 3University of Texas at Arlington College of Nursing and Health Innovations, Arlington, Texas, USA

- 4Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware Dover, Delaware, USA

Received: January 19, 2025; Published: January 24, 2025

Corresponding author: Dr. John Lowe, University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing, Austin, Texas, USA

DOI: 10.32474/LOJNHC.2025.03.000173

Abstract

Purpose: There is no sufficient health data available on marginalized First Contact Native American Colonial Era Native American Tribes (NACET) along the east coast of the United States (U.S.) that can address their health status and needs. Insufficient availability of health status data among colonial era Native Americans and their tribal communities are creating challenges for health systems to develop health promotion, prevention, and care programs that properly support their needs. To address these needs, this study conducted a collection of health status data among Native Americans from these marginalized colonial era tribes along the east cost of the U.S.

Methods: The study employed a mixed method design. A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted from a purposive sample of participants. A tailored tribal-specific Native American Health Survey version of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) was developed for the study. The tailored health survey allowed for the collection of health descriptive data from 125 participants within marginalized tribes along the east coast of the U.S. Twenty-five of the participants agreed to an audio-taped interview post completion of the survey for further exploration of their experiences regarding cultural knowledge, beliefs, values, and practices. Participant qualitative descriptive results were analyzed using Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) method for categorization of their data into specific themes by means of the research team’s discourse, external auditing, and agreement.

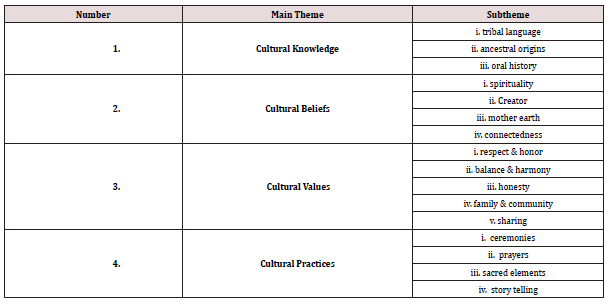

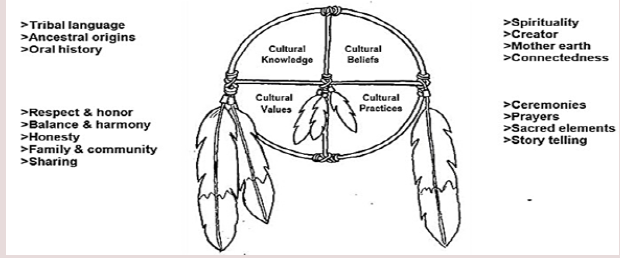

Results: The cross-sectional descriptive participant results identified diabetes mellitus and coronary as the most prevalent chronic health conditions reported. The participant results also identified that being uninsured had a critical impact on accessing healthcare by preventing Native Americans from marginalized tribes from seeking healthcare services and resources. “Four themes related to Cultural Knowledge, Cultural Beliefs, Cultural Values, and Cultural Practices and sixteen subthemes related to tribal language, ancestral origins, oral history, respect and honor, balance and harmony, honesty, family and community, sharing, spirituality, creator, mother earth, connectedness, ceremonies, prayers, sacred elements, and storytelling emerged from the participants’ qualitative data.”

Conclusions: Understanding the interactions between women and men within specific social contexts is crucial for addressing health disparities among marginalized tribal communities. Existing research indicates that gender relations are contextually aligned with social determinants of health and are closely linked to resilience.

Keywords: Marginalized Colonial Era Tribes; Health Status; BRFSS survey

Introduction

There is a critical need to collect health status data among marginalized First Contact Native American Colonial Era Tribes (NACET) along the east coast of the United States (U.S.). currently, these marginalized Native American population along the east coast includes approximately one million people. [1] These tribes, who first encountered European colonizers in the 1600s, have maintained continuous tribal identities through colonial treaties, reservations, Indian schools, state recognition, and federal documentation. tribal communities have maintained continuous tribal community identities, with a history of colonial and federal government contact through colonial treaties, reservations or designated “Indian towns,” enrollment in Federal Indian Schools or associated Indian Mission Boarding Schools, state recognition, and other relationships. [2] Jim Crow laws that furthered the marginalization, segregation, and discrimination for many of these communities resulted in a continuous negative impact on their health and well-being. [3] In 1852, for example, one eastern state’s General Assembly passed a stringent racially discriminating law, which stated that “It shall be unlawful for any Indian or Indians (Native Americans) to remain within the limits of this State, and any Indian or Indians that may remain, or may be found within the limits of this State, shall be captured and sent west of the Mississippi. [4] This Act removed any possibility of those Native Americans to openly live traditional lifestyles, much less identify themselves or be identified as members of a Native American tribe.

However, the law did not prevent Native Americans from creating settlements separate and distinct from White or Black communities. [5] Thus, most traditional practices and lifestyles remained hidden in remote areas along the eastern seaboard. If such a law was violated, these Native Americans came under direct threat of removal or death. [6] Today, such a policy is called ethnic cleansing. [7] Due to these experiences and policies, these tribal communities are ineligible to receive health care services from the Indian Health Service (IHS), the federal agency within the US Department of Health and Human Services responsible for providing health care to tribes [5].

Native Americans face the highest mortality rates among all racial groups. They experience 4.6 times the rate of liver disease-related deaths, 3.2 times the rate of diabetes-related deaths, 1.1 times the rate of heart disease-related deaths compared to other races, and reported some of the highest rates of psychological distress, such as substance use, suicide. [7,8] Studies are needed to illuminate additional challenges that marginalized Native American tribal communities experience regarding health disparities, access to health resources, poverty, land dispossession, displacement, homelessness, marginalization, cumulative historical trauma, and mental and medical health illnesses. [9] Additionally, studies need to be conducted to examine current challenges that adversely impact the quality of life, health, and wellbeing of east coast marginalized Native Americans that include industrial activity, climate change, rurality, environmental racism, structural and discriminatory laws and practices, limited access to health care and its resources due to geographic location, health and social demographic data misclassification, and factors such as systemic and structural racism. [10] Thus, despite a very great need, health promotion services offering culturally grounded prevention programs are lacking for marginalized Native Americans living along the east coast due to insufficient resources. Current health data that is being collected among Native Americans in the U.S. does not include these marginalized tribes. Thus, there is no sufficient health status data available to address health needs, making it difficult for health systems and programs to be developed to appropriately target these communities.

Methods

Design and participants

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted. [11] The study employed a mixed method design and included a sample of 125 Native American adults from marginalized colonial era tribes along the east coast of the U.S. Before completing the questionnaire and interviews, all participants had to read a brief description of the research and information on the privacy and anonymity of data processing. Data was collected via phone, in-person, and electronically. A tailored tribal-specific Native American Health Survey version of the Centers for Disease Control Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) was developed for the study. The BRFSS is the premier system of health-related telephone surveys within the U.S. [12] The tailored tribal-specific Health Survey allowed for the collection of health descriptive data from members of several tribes considered to be marginalized along the east coast. This allowed for the establishment of baseline health descriptors for each participating marginalized tribe as well comparison with national data for non-marginalized tribes and the general population.

Study variables

The following sociodemographic variables were collected: age, gender, education, and income. The tribal-specific Native American Health Survey was developed by tailoring the BRFSS. The BRFSS survey is conducted in all 50 states, but the Native American population is underrepresented in many state-focused BRFSS reports. [12] Native Americans are less than 1% of the U.S. population and because of this, federal and state health survey sampling methods are often inadequate in reaching the Native American population. Small sample sizes lead to limited data and consequently to insufficient information for certain subpopulations and demographic categories with which to make decisions about healthcare delivery and health policy. With limited sample sizes, data is often aggregated with the ‘other’ race category or with several years of Native American data.

As such, public health practitioners, researchers, and health care providers as well as tribal governments and health systems do not have accurate and necessary data to measure health risk behaviors, study health disparities, and improve health promotion and disease prevention programs especially among east coast marginalized tribes. This study is the first to develop a report on health status of several marginalized tribes along the east coast, which can be compared to data from non-marginalized Tribal Epidemiology Centers and BRFSS nationally. Findings have critical value to inform future research and planning for resource allocation and strategic planning for the health and wellbeing of marginalized tribes.

Data collection

Data collection was done via the tribal-specific Native American Health Survey tailored from the original BRFSS. Data collectors were trained to use the tribal-specific Native American Health Survey that was programmed on an iPad and provided to each data collector. They guided participants through the survey via in-person face to face, phone, or electronically. Each participant that completed the survey received a gift card incentive. The responses to the tribal-specific BRFSS were entered directly into the program on the iPad which were recorded within the REDCap iCloud data storage system. [13] Reported in this paper are the responses to questions pertaining to 1) perception of general health, 2) chronic conditions, 3) health care access, and 4) cultural knowledge.

Additionally, participants were asked to consider being interviewed post the completion of the survey. A total of 25 participants agreed to be interviewed. The interviews were audio-recorded, which allowed for deeper exploration of each participant experiences regarding cultural knowledge, cultural beliefs, cultural values, and cultural practices. An additional gift card incentive was provided to those participants who agreed and provided written consent to be interviewed.

Data analysis

The analysis of the quantitative variables was performed on a data matrix in the SPSS statistical package for Windows (v.26., IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). [14] A descriptive analysis was performed, indicating frequencies and percentages for each of the questions. To establish rigor, the qualitative data was analyzed using Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) methods. The CQR method includes the process of categorizing data into specific themes by means of the research team’s discourse, external auditing, and agreement. [15] The researchers first examine the data independently and then come together to present and discuss their ideas until they reach a single unified version that all team members endorse as the best representation of the data. Analysis by means of CQR into central ideas within themes and subthemes was achieved. Categories that capture important themes and subthemes that emerged from the interviews were presented to the participating tribal leaders for review and acceptance.

Ethical considerations

Before answering the questionnaire, all participants had to read a brief description of the research and information on the privacy and anonymity of data processing. Prior to taking part in the study, all the participants were informed (both verbally and in writing) about the research objectives, asking them to sign an informed consent form. They were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw their informed consent at any moment. The current study was approved by the partnering tribal community leaders and the University of Texas at Austin Institutional Review Board (IRB) [study #0000296].

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

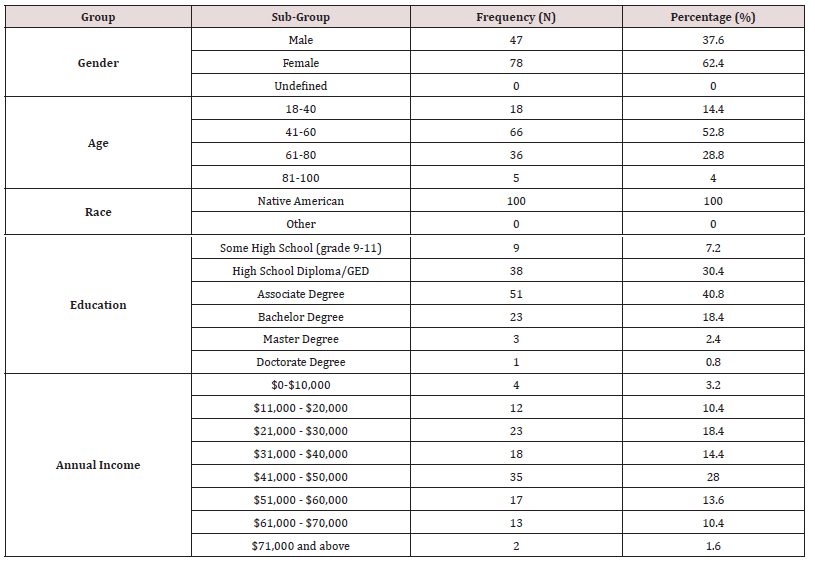

As displayed in (Table 1), the following sociodemographic characteristics of the sample include: 1) gender, 2) age, 3) race, 4) education, and 5) annual income. The study included 125 adult Native American participants with a mean age of 54.8 years The age reported was predominantly in the 41–60 category (52.8%), followed by the 61–80 group (28.8%), the 18-40 group (14.4%), and the 81- 100 (4.0%). The sample of participants who completed the survey was predominantly female (62.4%). Most of the sample (40.8%) earned an associate degree or higher with an annual income of $41,000- $50,000 (28%).

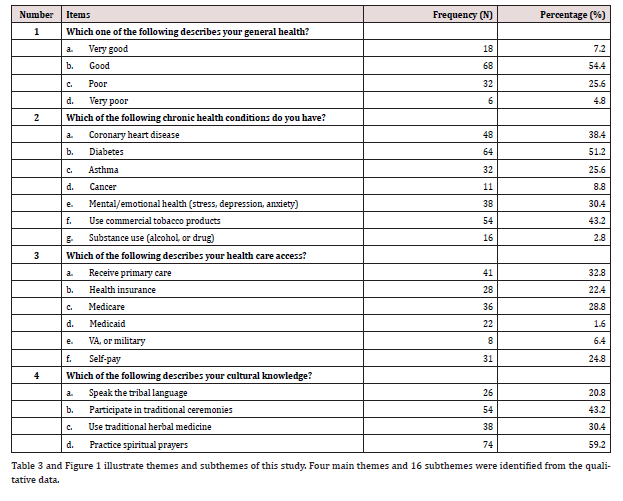

A total of 125 questionnaires were collected. No missing data was recorded. (Table 2) shows the results of the health survey questions regarding health experiences related to perceived general health, chronic health conditions, health care access, and cultural knowledge. Almost half of the participants (54.4%) responded that their perceptions about general health are good. Also, 25.6% indicated poor and 4.8% indicated their perceptions about their general health as being very poor. Participants (51.2%) identified diabetes as their predominant chronic health condition followed by use of commercial tobacco (coronary heart disease (43.2%). Availability of primary care was indicated by 32.8% of the participants along with 22.4% of the participants indicating they currently have health insurance. Other types of health care coverage include Medicare (28.8%), Medicaid (1.6%), and military or veterans’ health care services (6.4%). Participants (24.8%) identified that they had to self-pay for health care. Cultural knowledge related to Practicing spiritual prayers was the predominate relationship to cultural knowledge by 59.2% of the participants. The importance of participating in traditional cultural ceremonies was also indicated by several participants (43.3%).

(Table 3) and Figure 1 illustrate the main themes and subthemes of this study. Four main themes and sixteen subthemes were identified from the qualitative data.

Theme 1: Cultural knowledge

All the interviewees emphasized the significance of cultural knowledge, asserting that this formed the basis for maintaining an identity as Native American. “Our origins ancestrally must be known and be remembered” (P06). It is important that our history continue to be orally passed to future generations” (P10). Moreover, the participants emphasized the significance of knowing the tribal language, “who we truly are is steeped in the language” (P12). “Sometimes messages can be only communicated in our own tribal language and not in any other language as it does not translate” (P09). “Often, we make a fire and have our young sit with us as we share stories about how we were created and where we came from” (P03). Participants also highlighted how communication and sharing of their history happened orally. “We practice and use an oral tradition as a way to communicate with each other and pass along wisdom to our young” (P11). Three subthemes emerged from the theme of cultural knowledge: 1) tribal language, 2) ancestral origins, and 3) oral history.

Theme 2: Cultural beliefs

The results indicate that participants considered cultural beliefs as a significant element. Participants noted spirituality plays a very important role in the lives of people from marginalized tribes, “without our spirituality, we would not have survived hundreds of years of oppression” (P07). “Being connected to our Creator and each other is a foundational key element that has sustained us throughout many atrocities” (P18). Participants noted that the belief of being connected to all things serves as a resource. “Creator has provided all that we need to sustain us; that is why we must honor and take care of mother earth” (P21).” I would go hunting with my father, grandfather, and uncles who showed me how to ask the deer family to sacrifice one of theirs so that we could have food to eat, and we would always stop and give thanks for the sacrifice” (P16). Four subthemes emerged relating to cultural beliefs: 1) spirituality, 2) Creator, 3) mother earth, and 4) connectedness.

Theme 3: Cultural values

Five subthemes emerged pertaining to the theme of cultural values: 1) respect and honor, 2) balance and harmony, 3) honesty, 4) family and community, and 5) sharing. Respect and honor were emphasized by the participants to approach every encounter with others. Without respect and honor, relationships and interactions with people become meaningless. “I was taught from an early age that we should live honorably which means we must demonstrate being respectful for all living things” (P23). “Everything the Creator has created, even plants and animals, we are related to and therefore we must respect and honor them as this is showing that we respect our Creator” (P08). Several participants who were interviewed indicated balance and harmony were key elements in how every situation should be approached.

“It is important that we keep our focus with the intention of always seeking to be in balance and harmony” (P17). “The well-being of our community as a whole is emphasized over individual gain which demonstrates harmony within family, tribe, and the broader society” (P20). “Family is everything to us as this is how we stay grounded into who we are” (P05). The participants also noted the importance of honesty that must be role modeled and demonstrated to younger generations. “Being honest is a way to reflect respect for our families and communities” (P19). “We must strive to be honest in everything we say and do” (P14). Participants noted that sharing one’s resources was a way to not be selfish and to be aware of communal needs. “Whenever someone came to our house, my parents always shared food and a meal with our visitors” (P03). “My parents and grandparents would comment that we are our sisters and brothers’ keepers” (P22).

Theme 4: Cultural practices

The participants indicated that cultural practices must be continued so that they are not lost. “We always pray and communicate our gratitude for everything that Creator provides for us” (P04). “Our ceremonies keep us grounded and helps us to remember who we are as Native Indigenous people, and this should always be a part of our way of life” (P13). “My father and grandfather had my siblings, and I participate and learn the meaning of our ceremonies” (P25). Participants also commented that their history and culture are communicated through story telling. “Many of our beliefs, values, and traditional ways are passed along through our story telling” (P01).

“Story telling can be a fun way for our young to learn about how to live as a Native person”. Participants remarked the need for following what was taught by elders, “I was taught by my mother the sacredness of everything that Creator created” (P02). The knowledge regarding how to use what Creator provided came from my mother and grandmother” (P24). “We were taught by my mother how to use plants and herbs as medicine, and she shared that this knowledge came from her mother and grandmother” (P15). Four subthemes emerged from cultural practices: 1) ceremonies, 2) prayers, 3) sacred elements, and 4) story telling.

Discussion

This mixed methods study collected health data and cultural perspectives among 125 tribal members of marginalized colonial- era tribes along the east coast of the U.S. The tribal specific Native American Health Survey, adapted from the BRFSS, was utilized to collect quantitative data. In-depth interviews were employed to collect qualitative data among a subset of 25 participants. In this discussion, various aspects of the data are explored regarding the sociodemographic of the participants along with their health experiences related to perceived general health, chronic health conditions, health care access, and cultural knowledge and themes/subthemes from the qualitative interviews.

As for this study, diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease were the most prevalent chronic health conditions reported among the participants. Diabetes mellitus significantly contributes to elevated rates of coronary heart disease within this population. [16] These findings coincide with other related studies. [11] Individuals with diabetes are two to four times more likely to develop cardiovascular disease compared to the general population.

Several participants noted the lack of health insurance as a significant barrier to accessing and affording healthcare services. Many Native Americans from marginalized tribes face multiple financial responsibilities, further hindering their ability to pursue primary care, treatments, or medications. These gaps in insurance coverage are especially concerning given the extensive health disparities Native Americans experience compared to the general population. [16-17] While this topic has not been specifically researched among marginalized tribes, studies reported in the literature indicate that Native Americans often base healthcare decisions on their perceived ability to afford services, rather than on medical advice or their own desire to seek care. [16] Services from the Indian Health Service (IHS) has profound health and economic impacts. [18] However, this vital resource is unavailable to marginalized colonial-era tribes, further exacerbating health disparities within these communities. Furthermore, the absence of eligibility for federally funded services, denies these tribes access to other critical resources, such as funding for programs and the establishment of community health centers. [19]

This highlights the critical impact of being uninsured on accessing healthcare, an area that remains unexplored for marginalized tribes. Lack of insurance or underinsurance prevents tribal members from seeking healthcare services and filling essential prescriptions. Addressing these gaps may involve increasing education about available insurance options, enrollment processes, and the benefits of Medicaid expansion. These findings emphasize the necessity of further research into this underexplored area and underscore the importance of promoting tribal sovereignty and expanding resource access for marginalized tribes that lack access to healthcare services through the IHS. Such efforts are crucial for addressing existing health disparities and improving healthcare equity for marginalized tribal communities. Cultural knowledge, beliefs, values, and practices emerged as main themes from the qualitative interviews. Subthemes further expounded each of the main themes. Participants described relationships with parents and grandparents as crucial to learn and identify culturally as a Native American. Mothers and grandmothers were acknowledged as the knowledge holders of traditional plants and medicines. Fathers and grandfathers were described as wisdom keepers regarding the role of ceremonies and spirituality.

These findings are consistent with literature that describe how before the imposition of patriarchal colonial norms, gender relations among Native American communities were characterized by complementarity and egalitarianism. [20] However, there is a lack of research on contemporary gender relations within marginalized Native American communities. Understanding the interactions between women and men within specific social contexts is crucial for addressing health disparities among marginalized tribal communities. Existing research indicates that gender relations are contextually aligned with social determinants of health and are closely linked to resilience [8-10, 20].

Limitations

This study has important limitations that are noted. The findings are not intended to be generalizable due to the immense diversity among Native American tribes in the United States. As a result, these outcomes may not be applicable or relevant to other tribal communities. Additionally, participants were interviewed only once. Future research could benefit from conducting multiple interviews to evaluate potential changes in insurance status over time among marginalized tribes. Furthermore, future studies might consider including interviews with healthcare providers to explore their perspectives on how insurance status impacts healthcare access and health outcomes among members of marginalized NACET communities.

Conclusions

This research fills a significant gap in the literature on the health experiences of marginalized tribal community members. It is the first study to gather participatory-driven health status data from various east coast tribes that are not eligible for healthcare services provided by the IHS. By utilizing the tribal-specific Native American Health Survey, the study facilitates robust comparisons with national data. Marginalized NACET communities face considerable challenges, including chronic disease, premature mortality, and diminished quality of life. These challenges are shaped by a range of health determinants operating at individual, community, and systemic levels. Addressing modifiable determinants presents an opportunity to reduce health disparities in these communities, emphasizing the importance of region-specific data from the east coast. Furthermore, adopting a gender relations framework offers valuable insights into how family resilience and wellness are influenced by interactions between men and women and the socio-structural contexts of marginalized tribal communities. This approach is particularly pertinent for these communities, where historical oppression has deliberately disrupted traditionally egalitarian gender norms.

Author contributions: Conceptualization, J.L. and E.M.; methodology, J.L., E.M., and C.X-H.; formal analysis, J.L. and R.W-T.; investigation, J.L., E.M., and D.C.; resources, J.L., C. X-H., E.M., and D.C.; data curation, R. W-T. and M.K.; writing-original draft preparation, J.L. and E.M.; writing-review and editing, J.L., R. W-T and M.K.; supervision, J.L., E.M. and D.C.

Supplementary materials: A limited and more restrictive plan for data sharing for the proposed project is required for the proposed study because it involves a collaboration with Native American communities. There are specific and justifiable concerns among Native American communities about research, that has led to research distrust and the need to provide additional safeguards to protect this community to ensure risks (e.g., group harm, stigmatization, and privacy vulnerabilities) are mitigated.

This is recognized in the “Supplemental Information to the NIH Policy for Data Management and Sharing: Responsible Management and Sharing of American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) Participant Data”, which also supports AI/AN tribes in guiding this sharing plan: “AI/AN Tribes have legal rights to determine the conditions by which their data are shared when data are collected within their jurisdiction, including requiring Tribal approvals or participating in research review requests”. For this study, the research data are owned by tribal community partners. Requests for data for research purposes, with an outline of the data requested and the analyses that are being proposed, can be submitted to the authors who will review the request and discuss with the tribal leaders of the participating tribal communities for review and approval.

Funding acquisition: All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Funding: This research was partly funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, grant number RWJ-79660.

Institutional review board statement: This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the partnering tribal community leaders and the University of Texas at Austin Institutional Review Board (IRB) [study #0000296].

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement: The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Public Involvement Statement: No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement: The manuscript was drafted against the Checklist for reporting results using observational descriptive studies as research designs [46].

Use of Artificial Intelligence: AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- US Department of Health & Human Services (2023) American Indians and Alaska Natives: What are state recognized tribes? Administration for Native Americans. Archived from the original on November 15, 2023.

- Robbins RL (1992) Self-determination and subordination: The past, present, and future of American Indian governance. In The state of Native American: Genocide, colonization, and resistance. Brooklyn: South End Press.

- Anderon G (2014) Ethnic cleansing and the Indian: The crime that should haunt America. (2014) Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Andersen G (2019) The conquest of Texas: Ethnic cleansing in the promised land, 1820-1879.Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Smith J Douglas (2002) "The Campaign for racial purity and the erosion of paternalism in Virginia, 1922-1930: "Nominally white, biologically mixed, and legally Negro." Journal of Southern History 68, 1: 65-106.

- Sherman, Richard B (1988) "'The Last Stand': The fight for racial integrity in Virginia in the 1920s." Journal of Southern History. 54(1): 69-92.

- Smith J David (1993) The eugenic assault on America: Scenes in red, white and black. Fairfax, Va: George Mason University Press.

- O Keefe VM, Cwik MF, Haroz EE, Barlow A (2021) Increasing culturally responsive care and mental health equity with indigenous community mental health workers. Psychological Services, 18(1): 84-92.

- Buxbaum L, Hubbard H, Liddell JL (2023) It adds to the stress of the body”: Community health needs of a state-recognized Native American tribe in the United States. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 10(1): 62-83.

- Masotti P, Dennem J, Bañuelos K, Seneca C, Valerio-Leonce G, et al., (2023) The culture is prevention project: Measuring cultural connectedness and providing evidence that culture is a social determinant of health for Native Americans. BMC Public Health. 23(1):741-752.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, et al., (2014) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. International Journal of Surgery 12(12):1495-1499.

- Marks JS, Mokdad AH, Town M (2020) The behavioral risk factor surveillance system: Information, relationships, and influence American Journal of Prevention Medicine. 59(6): 773-775.

- Patridge EF, Bardyn TP (2018) Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). Journal of the Medical Library Association (JMLA) 106(1): 142-144.

- IBM (2014) How to cite IBM SPSS statistics or earlier versions of SPSS.

- Hill CE, Knox S, Thompsom BJ, Nutt Williams E, Hess SA, et al., (2005) Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 52: 196-205.

- Breathett K, Sims M, Gross M, Jackso EA, Jones EJ, et al., (2020) American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Cardiovascular health in American Indians and Alaska Natives: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 141(25): e948-e959.

- Poudel A, Zhou JY, Story D, Li L (2018) Diabetes and associated cardiovascular complications in American Indians/Alaskan Natives: A review of risks and prevention strategies. Journal of Diabetes Research.

- Jaramillo ET, Willging CE (2021) Producing insecurity: Healthcare access, health insurance, and wellbeing among American Indian elders. Social Science Medicine, 268 (113384).

- Liddell JL, Lilly JM (2022) There's so much they don't cover: Limitations of healthcare coverage for Indigenous women in a non-federally recognized tribe. SSM Qualitative Research Health, 2 (100134).

- Burnette CE, Sanders S, Butcher HK, Rand JT (2014) A toolkit for ethical and culturally sensitive research: An application with indigenous communities. Ethics and social welfare, 8(4): 364-382.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...