Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6695

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6695)

Creating a Virtual Clinical Experience for the ICU During the COVID Pandemic: A Case Study Volume 3 - Issue 2

Ronnie Sheridan*

- Creighton University College of Nursing, USA

Received: November 25, 2021; Published: January 12, 2022

Corresponding author: Ronnie Sheridan, CCRN alumnus, Assistant Professor, Creighton University College of Nursing, 3100 North Central Avenue, Office 706X, Phoenix, AZ. 85012, USA

DOI: 10.32474/LOJNHC.2022.03.000160

Introduction

Spring of 2020 was here. Another exciting journey was about to embark. Undergraduate baccalaureate students would begin their ICU rotation, the final care management course before moving on to their preceptorship and graduation. We were ready, clinical placements secured, assignments and rotations confirmed. No one could have imagined what was about to come next: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Restrictions were enforced, campuses transitioned to online-only learning. Both students and faculty experienced being quarantined and hospitals halted all on-site clinical experiences. Both leadership and faculty held firmly to the belief that our students should graduate on time while achieving program outcomes at their finest. It seemed impossible but no one stopped to question it, we simply kept moving toward our goal. The goal was to teach courses online and provide quality clinical experiences in a virtual environment with available resources and creativity. To meet this goal, each course group formed its workgroups to create a smooth migration from inperson classes and clinical to 100% online learning. The transition to online classroom learning came easily with the utilization of technology, which allowed us to continue the same active learning environments that we experienced daily. Breakout rooms online allowed for small learning groups and larger group discussions Goal met.

The real challenge was for each course work group to create clinical experiences for the online environment that equated to the same quality and excellence as those at the bedside without causing a delay in student learning or financial hardship on the institution. While faculty had a variety of technologies and resources available to them; the desire to create diversity with a variety of learning methods was evident if we wanted to keep learners engaged. The purpose of this case study is to provide nurse educators with an inside glimpse into the creation of a virtual clinical experience by one faculty member. The expectation is that this empowers faculty to move beyond the pandemic crisis to utilize their own creativity and create alternatives to on-site clinical experiences using a virtual environment without losing quality and without the need to purchase additional software.

Literature Review

For decades, meaningful nursing clinical experiences have become more difficult to attain. The answer to this dilemma was the development of simulation, which has evolved over the last 20 years. Today, many schools replace clinical time with simulation; as much as 25% to 50%. Findings from a systematic review of the literature revealed that there was no statistically significant difference between clinical placement or simulation when up to 50% of clinical time is replaced [1]. The literature is robust on this subject; however, many discussions explore what constitutes a true simulation and how do we measure its effectiveness? Many in academia have their own way of defining simulation and what they interpret as actual simulation [1]. This creates a concern when considering utilizing up to 50% of simulation to replace clinical. However, there are regulatory standards written that guide nursing educators on what simulation constitutes and how to develop quality experiences for students when following a set of standards [2-5]. Using these guidelines, many publishing companies have created their own lines of simulation scenarios and products for schools of nursing to purchase. Likewise, many schools of nursing have trained their faculty on the development and delivery of quality simulation experiences. Simulation includes a variety of technologies including task trainers, standardized patients, medium and high-fidelity mannequins, computer-based instruction including virtual and augmented reality [6]. Unfortunately, not all schools of nursing can allocate the funds to purchase all these products. Therefore, priorities are made on what best meets the curriculum objectives. Faculty are asked to provide additional assistance using the newest technologies and creativity while following regulatory guidelines and best practices for simulation.

Framework to Teamwork

As COVID raged and students were about to start their clinical ICU experiences, each member of the critical care course workgroup assembled to identify the clinical objectives that were to establish competency for this clinical. Because of the time demands, each member took certain objectives and worked to create a variety of online clinical experiences. The team was aware that there was a state nursing board waiver to exceed 50% of simulation (2:1 ratio) online due to the pandemic; however, it was decided by our team to adhere to a 1:1 simulation ratio. Later, upon evaluating some of the learning experiences, it was apparent that with enhanced evaluation processes and research, that a 2:1 ratio may have been appropriate. To provide a framework for the development of virtual simulations, the team adhered to the standards set forth as best practices [3,5]. These standards guided each faculty member in their creation of an online clinical experience. The team was able to utilize our online learning management system to organize and deliver each of the experiences.

Creating a Virtual Clinical Experience

This author was assigned to meet objectives for performing health assessments, evaluating evidence-based care management interventions, collaborating with members of the interprofessional health care team, demonstrating clinical judgment, and synthesizing knowledge. To determine what clinical experience to create, the question first posed was how does an ICU rotation begin and what will the students be missing by not being on-site? The answer came quickly; orientation to the ICU, learning the units, the routine, the nurses, and the equipment. After orientation, the student experiences working on an ICU unit with two patients to provide care for, along with their preceptor RN and their clinical instructor as a guide. A typical day in the ICU allows a nursing student to observe and take part in a variety of activities that require critical thinking, clinical judgment, and continuing to learn the nursing process in action. Within this paper are the details that describe how both experiences were emulated using a virtual clinical experience online. This was accomplished using available technologies, a little creativity, and some wonderful volunteers.

Creating the Layout

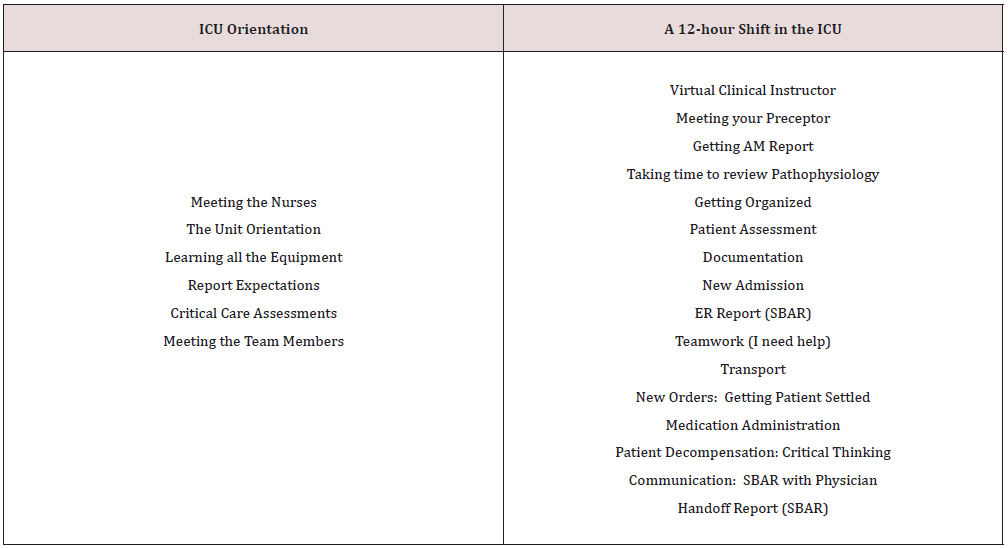

The first step to creating the modules for an ICU orientation and a 12-hour shift in the ICU was to outline what must be included (Table 1). Perhaps the most important aspect of the outline was to ensure multiple ways to evaluate learners just as they would be assessed by their clinical instructor when on-site at clinical rotations. For that purpose, stopping points were built into the outline at periods where knowledge could be assessed, application could be evaluated, and instructors would emulate Socratic dialogue. Another important aspect was to keep students engaged and interested in what they were learning. To promote realism into the virtual clinical experiences a variety of media were utilized including You Tube instructional videos, pictures with explanations, videos of live people, pictures with audio dialogue, and a picture of a computer, with computer automated articulation, that acted as a virtual clinical instructor. Each item was vested by a work team of faculty before using it to ensure accuracy, best practice, and alignment with the curriculum.

Orientation to the ICU

This module was entitled “Welcome to Complex Adult Care in the ICU (A Virtual/Simulated Tour Experience)”. Students were welcomed to a virtual tour of the world of Critical Care Nursing. Within the Introduction is a brief explanation that critical care nurses have a very specific skillset and the types of units they work. Additionally, information about critical care certification opportunities is shared. Finally, the purpose of the module is listed with three objectives that are mapped to the clinical objectives and program objectives. Each page of the module, within the learning management system, was embedded with pictures to make the dialogue more engaging. Once introduced to the unit, students were able to meet two ICU nurses by watching a video with the ICU nurse sharing dialogue about their responsibilities and their experiences. This was a perfect stopping point for students to write and submit a reflection on the roles of the ICU nurse as they perceive it from this exercise. Any artifacts submitted by students were reviewed with timely feedback from their live clinical instructor. Being in the ICU can be very distressful to students due to all the equipment, the sounds, and the hurried atmosphere. Therefore, a page within the module was created called “What is all this stuff?”. On this page, students were able to observe an RN giving an entire tour of an ICU room including all the equipment that would be utilized within the ICU such as monitors and ventilators. In addition, a You Tube video explaining what to expect in the ICU was available for student viewing. The next page demonstrated various IV pumps that are utilized and provided step-by-step instructions on how to utilize multiple pump infusers when multiple drips are necessary. Once the infusion pumps were reviewed, students went to the next page where ICU drips were reviewed using brief written explanations along with blackboard drawing videos for paralytics, sedation, vasopressors, inotropes, vasodilators, antiarrhythmics, and analgesics. Moving forward from this page students were introduced to a new page where titrating drips in the ICU presented real-life scenarios requiring drug math calculations and pump settings by the students. Each page included brief dialogue followed by videos to enhance the students learning, along with stopping points to ask students questions or have them solve problems. All student responses were reviewed by their live clinical instructor with robust feedback.

Central monitors are an essential part of the ICU and monitoring the patient’s hemodynamic status. Therefore, the module continued a page on central monitors showing a video of how to use the patient monitor. In addition, arterial lines, pulmonary catheters, and central lines were introduced through brief dialogues, pictures, and video instructions to help students make the connection in hemodynamic monitoring. Early in the module, mechanical ventilators were introduced briefly as the students engaged in a tour of the ICU patient room. Next, the students received a broader view of the mechanical ventilator by watching a patient be intubated through rapid sequence intubation (RSI). Once the patient was safely intubated and placed on the ventilator, students watched a video on how the mechanical ventilator operates and how to make the settings or change the settings. Likewise, alarms were discussed and how the nurse assists the respiratory therapist in this role. Various pictures and descriptions were provided for yankauer suctioning, open in-line suctioning, and closed in-line suctioning. This page was completed with a video about Ventilator- Associated Pneumonia (VAP) to integrate evidence-based practice.

Through this orientation module, the student has experienced a variety of learning methods to understand the ICU and the responsibilities of the RN. The students move on to participate in an activity with a 60-year-old male from the medical-surgical unit who has decompensated and is going to arrive in the ICU in five minutes. The student is required to prepare for RSI and hemodynamic support to prepare for their patient. The student is presented with a series of questions related to RSI, hemodynamic parameters, IV drips, pathophysiology of the patient, a picture of a mechanical ventilator screen with settings that are to be reviewed and discussed. The live clinical instructor reviews the student’s responses and provides both synchronous and asynchronous feedback. In the next module, students will be participating in ICU communication, both verbal and written. Therefore, an additional page on ICU report using SBAR allows students to review some examples of ICU report sheets and choose one. Once chosen, they can watch and take report from an ICU nurse on pre-recorded video. To determine competency, students repeat this activity; however, they turn in their report sheet to their live clinical instructor for feedback. At this point, students have learned all about the ICU unit, the equipment, and most of the RN’s role. However, because the ICU patient is complex and requires an in-depth assessment, students watch two videos where ICU nurses are assessing patients, both responsive and non-responsive. To complete their orientation, the students are introduced to various team members such as the respiratory therapist, the ICU intensivist, the pharmacist, and the dietician. Each of these includes a video of the individual explaining their role. To conclude the module, students are asked to reflect on their orientation to the ICU and key takeaway points that each learner has experienced. Within this module are 10 virtual simulation pages provided via picture/audio or video. In addition, four application pages allow students to demonstrate their understanding and receive feedback from their clinical instructor. The day ends with a synchronous post-conference to allow students to ask questions and clarify any muddy points.

A 12-Hour Day in the ICU

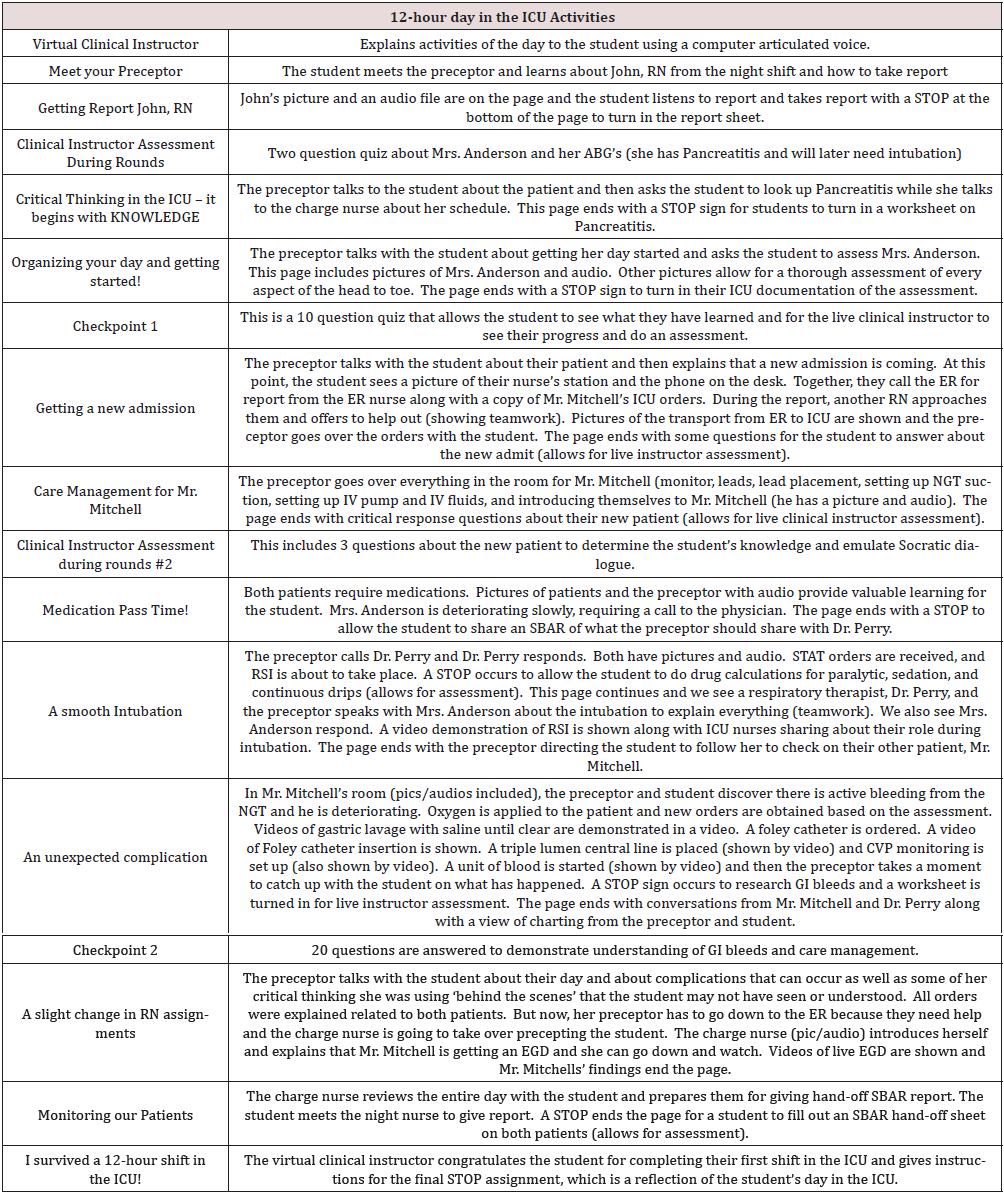

Unlike the orientation to the ICU, the 12-hour day in the ICU contains more real-life, in-the-moment interaction between students and the virtual environment. Most of the hospital staff have their pictures posted with audio files next to them so that students can listen to their voices and follow along with the unfolding day. The overview for this day follows a typical day in the ICU including meeting your preceptor, clinical instructor assessment during rounds, critical thinking in the ICU, organizing your day and getting started, getting a new admission, care management for Mr. Mitchell, medication pass time, a smooth intubation, an unexpected complication, a slight change in RN assignments, monitoring our patients, and finally, I survived a 12-hour shift in the ICU! Each of these pages throughout includes checkpoint quizzes and clinical instructor assessment during rounds with feedback from a live clinical instructor. Students begin their day by meeting their preceptor. The preceptor’s picture is on the page with an audio file next to it explaining that they are about to get report from John, the night RN who had a patient die and received a new admit. Again, there is a picture of John and an audio file. The student receives a report sheet from the preceptor and uses this to take report. At the end of this page, there is a STOP sign instructing the students to turn in their report sheet. Students receive feedback from the live clinical instructor who is following along at the same time as the student. During the 12-hour clinical day, each student is caring for two patients. Mrs. Anderson, who has pancreatitis and eventually requires intubation, and Mr. Mitchell, who is a new admission with a Gastrointestinal Bleed. Throughout the care of these two patients, the students experience a variety of activities (Table 2). While the student progresses through the various pages of the module in the learning management system, the live clinical instructor (1:10 ratio) provides feedback promptly throughout the clinical day. This activity was run synchronously, but we quickly realized it could also be asynchronous. Again, the variety of activities included pictures and audios of various team members, pictures of equipment, and You Tube videos of live demonstrations.

Conclusion

These modules were created in response to COVID-19 and on a very tight timeline. Improvements are being made to provide even more realism and actual videos from local hospital sites to enhance the student experience. Early anecdotal responses from students were positive and students shared that these experiences allowed them to “feel as if” they had been in the ICU unit for a day. As students moved onto preceptorships the next term, anecdotal responses continued to be positive suggesting the virtual experience had prepared them to be within an ICU unit. Limitations were noted early in the delivery for the importance of having a live instructor available to answer questions and give immediate feedback to submissions. In addition, the modules require frequent monitoring to ensure that links remain operational. Thus, over time replacement with our own videos is paramount. Overall, the virtual clinical experiences demonstrated that faculty can, and should, be encouraged to create their own simulated scenarios for students using readily available technology resources. This method allows faculty to create simulated scenarios that are mapped to their curriculum while being cost-effective. Future research of these virtual clinical experiences is necessary to demonstrate their validity and reliability as a replacement for clinical time. Many thanks to the friends, family, and former students who provided the audios for this real-life experience. Nursing faculty are encouraged to explore this method of virtual reality as a way of preparing their students for new clinical settings.

References

- Larue C, Pepin J, Allard É (2015) Simulation in preparation or substitution for clinical placement: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Nursing education and practice 5(9): 132-140.

- Hayden JK, Smiley RA, Alexander M, Kardong-Edgren S, Jeffries PR (2014) The NCSBN national simulation study: A longitudinal, randomized, controlled study replacing clinical hours with simulation in prelicensure nursing education. Journal of Nursing Regulation 5(2): C1-S64.

- The International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning Standards Committee. (2016, December). INACSL standards of best practice: SimulationSM simulation design. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 12: S5-S12.

- Jeffries P, Adamson K, Rodgers B (2016) Future research and next steps. In Jeffries, P. (Ed.). The NLN Jeffries Simulation Theory [Monograph]. Wolters Kluwer.

- Lopreiato JO, Downing D, Gammon W, Lioce L, Sittner B, Slot V, Spain AE (2016) Healthcare Simulation Dictionary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Moran V, Wunderlich R, Rubbelke C (2018) Simulation in Nursing Education. Simulation: Best Practices in Nursing Education. Springer Cham.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...