Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6695

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6695)

A Worksite Health Promotion Project in The University Setting A Doctor of Nursing Practice Project Volume 3 - Issue 2

Kelly Crawford*

- Assistant Professor of Family Nurse Practitioner, Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond, Louisiana, USA

Received: October 28, 2021; Published: November 11, 2021

Corresponding author: Kelly Crawford, Assistant Professor of Family Nurse Practitioner, Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond, Louisiana, USA

DOI: 10.32474/LOJNHC.2021.03.000159

Abstract

Non-communicable diseases (NCD) have become the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. This public health issue has driven the development of innovative solutions, one of which has been implementing wellness programs at work. Historically, the university has been characterized as a low physical activity setting, which made it the perfect place to test the potential benefits of a workplace wellness program. This Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) project was designed to improve health behaviors in a satellite university faculty. The project implemented a 10-week worksite wellness program intervention comprised of education and walking. The intervention effectiveness was evaluated with American Heart Association My Life Check® (AHA MLC) online tool. Although there was not a significant difference between the pre-intervention heart scores (M=6.04, SD=1.66) and post-intervention heart scores (M=6.31, SD=1.57); t (19) =1.47, p=0.159), this project demonstrated improvements in several independent areas of the AHA MLC, which included weekly activity levels, overall cholesterol, increased fruit, and grain intake, and decreased sugary beverage intake. This project contributed to research by offering an example of how an innovative web-based wellness program could impact faculty health behaviors in a satellite university setting. Future studies are needed to identify types of wellness programs that yield positive results in various workplace settings.

Keywords: worksite wellness program; workplace wellness program; wellness program wellness program in the university setting

Introduction

Background and Significance

Non- communicable diseases (NCDs), rather than infectious agents, have become the primary source of illness among Americans. While these diseases have not been infectious or transmittable, they have been considered chronic and preventable. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and chronic lung disease have emerged as the most common NCDs [1] (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). NCDs have been directly related to increased mortality rates of 88% in the United States (US) and 70% across the globe [2] (WHO, 2014). The macro and microeconomic impact associated with NCDs has been substantial. Macroeconomic issues have included increased health care expenditures and lost labor and productivity for businesses and employers. Microeconomic issues have included increased personal costs associated with disease treatment, work-related absenteeism, and lost personal independence [3] (WHO, 2009). Risk factors for developing NCDs have included a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, stress, as well as alcohol and tobacco use. The American way of life has changed substantially since the 1950s, when more than 50% of the workforce was employed in physically demanding jobs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [4] [CDC], 2016b). Today, less than 20% of workers are in positions requiring physical labor. Technological advances have shifted labor from physically demanding jobs to service-oriented jobs requiring minimal strenuous activity. Occupations necessitating minimal physical activity have been classified as sedentary. Over the last half-century, there has been an 83% increase in sedentary work environments (American Heart Association [5] [AHA], 2015b). Both sedentary jobs and lifestyles have contributed to the development of NCDs.

Modern technological conveniences have resulted in decreased physical job requirements, altered eating habits, and increased sedentary leisure time. Improved access to public and private transportation has reduced the amount of time people spend walking to everyday activities, contributing to decreased daily movement [5] (AHA, 2015b). The 1970s heralded a shift in eating patterns. Readily available food options, in the form of processed and fast food, have replaced home-cooked, home-grown meal preparation. Additionally, food consumption volume has doubled, and overall levels of nourishment have decreased. This flip-flop in nutrition has resulted in obesity, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and immune system dysfunction [6]. While activity and nutrition have decreased, the average American is suffering from an increase in stress. Job stress has contributed to missed days at work and could lead to other unhealthy behaviors, including increased substance abuse, decreased physical activity, and unhealthy eating trends (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [7] [CDC], 2016a). For decades, Americans have been educated on the poor health outcomes associated with tobacco and alcohol consumption. Multiple forms of tobacco use have been linked to cardiovascular disease and different types of cancer. Heavy alcohol intake, classified as more than eight drinks a week for females and ten for males, has been linked with cardiovascular disease, liver impairment, highrisk sexual behaviors, accidents, and if consumed during pregnancy, can cause fetal harm [7] (CDC, 2016a). These changes have affected the population across all socioeconomic levels. Unfortunately, these evolutionary alterations have not improved physical and mental health, but have contributed to decreased physical activity, increased stress, poor nutrition, and continued alcohol and tobacco use [8] (AHA, 2015a). The burden of chronic disease has inspired the nation to examine innovative health improvement strategies. One solution has been the incorporation of worksite health promotion programs. These programs have been encouraged to offer onsite health-related activities to promote physical activity, proper nutrition, relaxation techniques, and tobacco and alcohol cessation for employees [9].

Sedentary work environments have unintentionally become poor health behavior breeding grounds. Less than ideal working conditions characterized by low activity levels, limited nutritional choices, and increased stress have contributed to poor health choices. Unfortunately, the university setting has been one such environment, defined by desk jobs, vending machines, and high-stress deadlines [10]. Nursing education jobs have long been considered sedentary, associated with mostly deskbound clerical tasks such as computer use, grading papers, and course development. As health promoters, an integral part of the nurse’s role has been to recognize negative health habits and develop programs to improve the health of individuals and society [11] (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2006).

Purpose and Significance

This project aimed to evaluate the effect of a worksite wellness program on faculty health behaviors at a satellite university campus. This study intended to determine if a workplace wellness program could improve health behaviors. Additionally, the project provided data to illuminate how employers could offset adverse health outcomes by implementing workplace health programs. This project helped university employees establish a worksite wellness program with the intent of increasing participants’ overall health. The project included evidence-based interventions and provided health and productivity research directed at satellite university faculty, which was generalizable to other similar professions. A needs assessment was conducted to determine the facility baseline wellness status using the CDC Health Scorecard (HSC). Each section of the HSC tool gave the facility a score based on the presence or absence of specific health activities. Categories with a low numerical rating identified areas of need. The results were as follows: tobacco control 11/19, nutrition 1/21, physical activity 6/24, weight management 0/12, stress management 10/14, depression 7/18, elevated blood pressure 2/10, cholesterol 0/15, diabetes 2/15, signs and symptoms and response plans for heart attacks, strokes, and occupational safety 22/22, and vaccine-preventable disease 6/18. According to the CDC HSC results, the lowest scores were in nutrition, physical activity, weight management, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. The employee wellness needs assessment focused on these areas and determined the best worksite wellness intervention for the project.

Method and Design

Considerations

Expedited approval for this quality improvement project was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern State University of Louisiana and Southeastern Louisiana University prior to initiation. Approval was based on the probability of no greater than minimal risk to the participants.

Participants and Setting

Convenience sampling was used for participant recruitment by campus email. The naturalistic study setting was the university satellite campus. The campus was comprised of classrooms, offices, and a library. Classrooms were rectangular with desks and chairs and short carpet. The campus outside was flat, even pavement conducive for an activity intervention. The intervention and data collection settings varied from individual and small groups to indoor and outdoor campus areas.

Intervention

Phase one of the study was the administration of the Alliance for a Healthier Generation EWIS to assess current wellness behaviors in employees and identify areas of need [12] (Alliance for a Healthier Generation, 2015). The EWIS survey was chosen because it was specifically designed to determine the needs and wants of employees in a school setting [13] (Alliance for a Healthier Generation, 2016). The survey examined healthy activities, including various types of exercise, health screening interest, weight and stress management, and nutritional education. Survey specifics have been discussed under the outcomes measured section. The results of the study were calculated and used to formulate a relevant intervention. The results of the EWIS revealed that employees were interested the most in dietary and nutritional education, followed by physical activity and stress management. This information was used to develop a 10-week wellness intervention that focused on nutrition and physical activity. The purpose of phase two was to deliver the wellness intervention to a group of 20 participants. Identification of one set day and time was impossible due to faculty schedule variations. Creating an intervention that offered participants flexibility was a project goal. Therefore, after researching various web-based tools, the DNP student created a centralized project content delivery area, where invited participants could access information on their own time. The university’s Microsoft Office 365 account was used to create a group site, upload content, and interact with study participants.

Each week participants had various videos and educational content they were asked to review. The educational content focused on Life’s Simple 7 and healthy eating videos from the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM). Life’s Simple 7 detailed seven steps that were associated with improved health. The seven steps were: managing blood pressure, controlling cholesterol, reducing blood sugar, getting physically active, eating healthier, losing weight, and smoking cessation [14] (AHA, 2017c). PCRM was comprised of healthy eating videos that encouraged a diet high in fruits and vegetables to improve overall heart and health status. In addition to the weekly educational information, participants were asked to walk half a mile twice weekly. Although participants were not required to submit proof of weekly walking at the end of the study, they were asked to identify if they completed this part of the project. Indoor and outdoor walking routes were mapped and provided for subjects. Subjects were expected to have the physical ability to complete the one-half-mile distance during the project timeframe. The AHA MLC was used, both pre and post intervention, to assess intervention effectiveness. The AHA MLC tool was developed specifically to evaluate WWP, making it appropriate for this project.

Outcome Measures and Instruments

All study participants completed the EWIS and MLC assessment tools. The EWIS was an anonymous two-part survey administered through Survey Monkey. The EWIS measured individual healthy activities and health behavior interests. The first part included 16 questions regarding healthy activities. The healthy activity list was comprised of the following: fitness plan development, exercise classes, dancing, team sports, walking, bicycling, yoga, etc., and also health screening, weight and stress management, and nutritional education. Participants indicated their level of interest by choosing one of the following: “very interested,” “might be interested,” or “not interested.”

The subsequent 12 questions evaluated participant interest in the following categories: health promotion programs, healthy snack options, and preferred physical activity types and times. These 12 questions were scored with a four to one Likert scale: “4=very likely,” “3=somewhat likely,” “2=not very likely,” and “1=not likely at all” [15] (Healthier Generation, 2016). The EWIS tool was offered as a free assessment from the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, which was founded by the American Heart Association and the Clinton Association [16] (American Heart Association, 2017a). The results of the EWIS were used to determine participant interest and develop a tailored wellness intervention. Although the validity and reliability of the EWIS survey were not available, the EWIS survey was supported by the AHA and used by the Wellness Council of America, The California Department of Public Health, and The United States Department of Agriculture as a recommended wellness assessment tool [17] (Healthier Generation, 2013). The MLC was an innovative science-based tool created by the AHA specifically for WWP. The MLC assessment tool evaluated seven behaviors associated with good health, also known as Life’s Simple 7. The key outcome measured by the MLC was an overall heart score, also known as an overall heart health score. The heart score was a valid and reliable measurement [18] (American Heart Association, 2017c). The original research study by [19] reported the Heart Score demonstrated good discrimination (Harrell’s c-index, 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71, 0.74 [females]; 0.77; 05% CI, 0.76, 0.79 [males]), fit, and calibrated.

Gathering the following information generated the overall score: smoking status, nutrition, activity, weight, blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood glucose. MLC obtained information such as age, height, weight, gender, and ethnicity, as well as seven additional questions, which included three questions on blood components such as cholesterol and blood glucose and four questions on daily activities such as fruit and vegetable intake and activity levels that impact health. The information was entered into the MLC online tool, and an individual heart score along with an action plan was generated. One feature of the MLC tool was that participants could access it multiple times, enabling them to track improvements over time.

Data Analysis

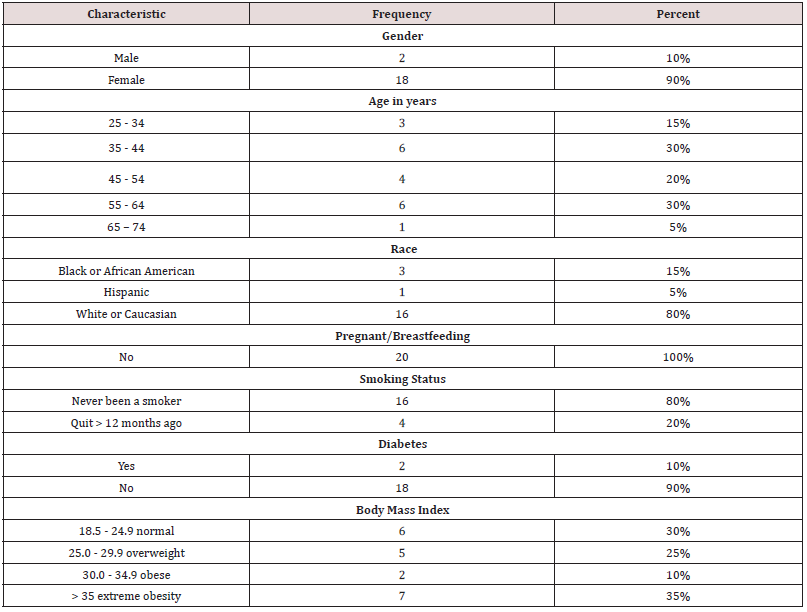

Demographic data were collected on the AHA MLC but not the EWIS. The demographic data and characteristics obtained, provided in Table 1, included gender, age, race, pregnant/breastfeeding status, smoking status, diabetes status, and BMI. Of the 20 study participants, 10% (n=2) were male and 90% (n=18) female and the age ranges in years were as followed 15% (n=3) were 25-34, 30% (n=6) were 35-44, 20% (n=4) were 45-54, 30% (n=6) were 55-64, and 5% (n=1) was 65-74. The study participants were Caucasian 80% (n=16) followed by African Americans 15% (n=3), and Hispanic 5% (n=1). None of the study participants reported being pregnant or breastfeeding. Ninety percent (n=19) of participants denied having diabetes; 10% (n=2) were self-reported diabetics. Regarding smoking status, 80% (n=16) identified as “never been a smoker,” and the remaining 20% (n=4) reportedly quit over 12-months ago. Finally, the sample study participants’ BMI was as follows: 30% (n=6) were 18.5- 24.9 normal, 25% (n=5) were 25.0-29.9 overweight, 10% (n=2) were 30.0-34.9 obese, and 35% (n=7) were classified as extremely obese. In summary, the majority of participants were female, age 35-44 or 55-64 years, Caucasian, never smoked, without diabetes, and classified as extremely obese.

American Heart Association My Life Check®

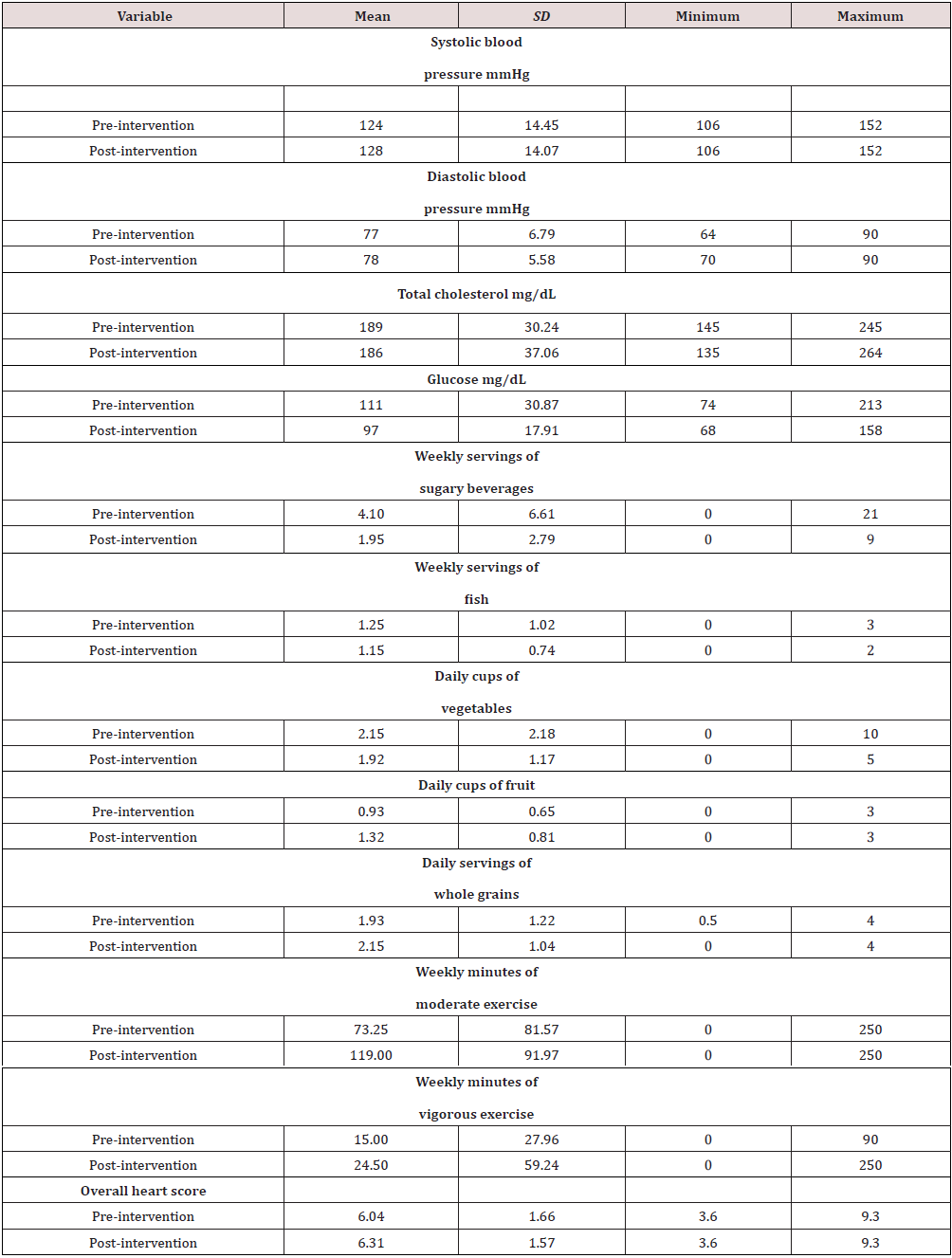

The AHA MLC online tool was used to calculate each participant’s overall heart score. The AHA MLC heart score was computed using participant demographics, underlying cardiovascular disease presence, blood pressure, glucose, total cholesterol, exercise, and dietary habits. All 20 participants completed the pre-intervention AHA MLC. The result of the pre-intervention AHA MLC has been reported in Table 2. The mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) was 124 mmHg, and the mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was 77 mmHg. The mean total cholesterol was 189 mg/dL, with the highest at 245 mg/dL and the lowest at 145 mg/dL. The mean glucose was 111 mg/dL, with the highest glucose recorded being 213 mg/dL, and the lowest was 74 mg/dL. Dietary habits were assessed in regard to sugary beverages, fish servings, fruits, vegetables, and grain consumption. The average number of sugary beverages consumed in a week was 4.1. The average number of fish serving was 1.25 per week. The average number of daily servings of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains was 0.925, 2.15, and 1.93, respectively. The preliminary data used to calculate the heart score also reported participant exercise activity as 73.25 minutes a week of moderate exercise and 15.00 minutes a week of vigorous exercise. This data, along with the demographic characteristics, were used to calculate participants’ heart scores. The mean pre-intervention heart score was 6.0, with the highest heart score being 9.3 and the lowest at 3.6 on a 0-to-10-point scale, with 10 representing the lowest risk for cardiovascular disease.

The AHA MLC online assessment tool was used to calculate each participant’s pre and post-intervention heart score. All 20 participants completed the post-intervention AHA MLC. The result of the post-intervention AHA MLC was reported in Table 2. The mean SBP was 128 mmHg, and the mean DBP was 78 mmHg. The mean total cholesterol was 186 mg/dL, with the highest total cholesterol at 264 mg/dL and the lowest at 135 mg/dL. The mean glucose was 97 mg/dL, with the highest glucose recorded being 158 mg/dL, and the lowest was 68 mg/dL. Dietary habits were re-assessed regarding sugary beverages, fish servings, fruits, vegetables, and grain consumption. The average number of sugary beverages consumed in a week was 1.95. The average number of fish servings was 1.15 per week. The average number of daily servings of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains was 1.32, 1.92, and 2.15. The final data used to calculate the heart score also reported participant exercise activity as 119 minutes a week of moderate exercise and 24.50 minutes a week of vigorous exercise. The mean post-intervention heart score was 6.31, with the highest heart score being 9.3 and the lowest at 3.6 on a 0-to-10-point scale, with 10 representing the lowest risk for cardiovascular disease.

Findings

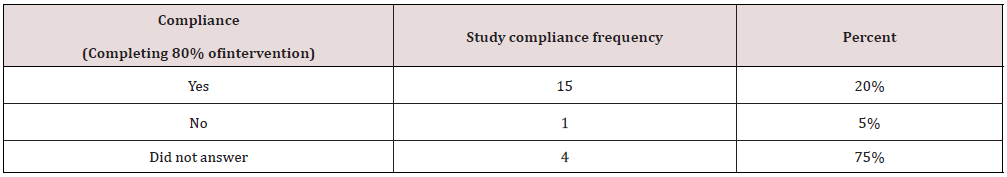

When comparing the pre and post-AHA MLC Mean (M) data (n=20), improvements were noted in several areas. In regard to nutritional intake Means: the weekly sugary beverage intake decreased from 4.1 to 1.95 servings, and the daily fruit serving intake increased from 1.93 to 2.15. Increases were seen in the Mean scores of both average weekly minutes of exercise from 73 to 119 and vigorous weekly minutes of exercise from 15 to 245. The average glucose and cholesterol decreased from 111mg/dL to 97 mg/dL, and 189mg/dL to 186 mg/dL, respectively. Finally, the Mean heart score increased from 6.0 pre-intervention to 6.3 post intervention. The project intervention was delivered in a flexible format where participants could access information at their leisure. This non-traditional design forced participants to be self-directed. Therefore, the post-intervention data also collected a response from each participant to assess study compliance, presented in Table 3. Compliance was defined as completing 80% of both the weekly intervention information sessions and the weekly walking. Of the 20 participants, 75% (n=15) reported study compliance, 5% (n=1) reported non-compliance, and 20% (n=4) did not answer the question.

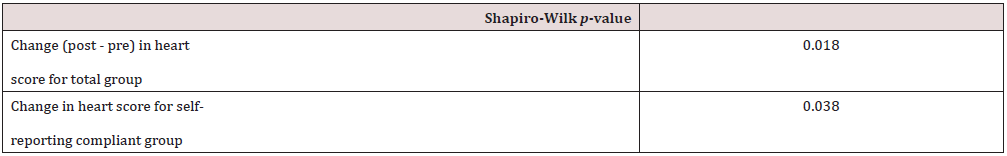

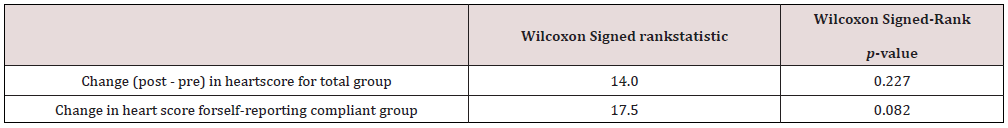

A paired t-test was used to compare the heart scores for participants’ pre and post-workplace wellness intervention for both the entire group (n=20) and separately for the group who reported study compliance (n=15); see Table 4. There was not a significant difference between the pre-intervention heart scores (M=6.04, SD=1.66) and post-intervention heart scores (M=6.31, SD=1.57); t (19) =1.47, p=0.159) for the total group; t (14) =2.14, p=0.051 for the compliant group. The Shapiro-Wilk test of normality (n=20) was performed and showed a significance of p=0.018 (α 0.05) which indicated data did not follow a normal distribution. Consequently, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for comparison. However, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (n=20) also showed no statistical significance (W=14; p=0.227). Tables 4, 5, and 6 have been provided with the statistical data information.

For several decades non-communicable diseases (NCDs) were responsible for the majority of deaths and disabilities worldwide [7] (CDC, 2016a). The impact of NCDs in the United States matched this disturbing trend. One of the most shocking features of common NCDs was the fact they have been considered preventable. Each year the NCD related death toll has continued to rise, which has made the issue a public health priority. Despite advances in NCD prevention, the number of people affected has continued to rise. The two main reasons for this increase were attributed to decreased activity and poor nutrition. Technological growth has altered the occupational environment, changing the way people work, leading to less daily physical movement. Compounding this activity issue has been the proliferation of processed and fast food consumption. These two major shifts in modern society have contributed to an increase in cardiovascular disease, the number one NCD associated with increased morbidity and mortality [7] (CDC, 2016a). The growing realization that declining employee health has become a global health concern has sparked employers to utilize the workplace as a wellness intervention site. Higher education settings, especially those focused on health education like nursing, have had a unique opportunity to foster collaboration between disciplines and departments to promote workplace wellness programs. Furthermore, higher education settings where faculty jobs are considered sedentary have provided an optimal setting for this project.

The main result of this DNP project, which consisted primarily of nutrition and activity interventions, was a mean heart score increase from 6.0 to 6.3 on a 0-to-10 point scale. The American Heart Association (AHA) My Life Check® (MLC) online total heart score tool evaluated intervention success. The AHA MLC was a recommended tool to evaluate overall health in the workplace [9]. In addition, key findings included improvements in total cholesterol, weekly sugary beverage intake, daily fruit, and grain intake, and weekly moderate and vigorous exercise. Improvements in inactivity and nutrition were consistent with the previous studies from [20,21]. There were no participants who dropped out of the study. The final data collection tool added a question on program compliance. Compliance was described as subjects completing 80% of weekly information sessions and the twiceweekly one-half mile walks. According to the final data collection tool, 75% of participants self-reported project compliance. Among the 20 program participants, the majority were Caucasian (80%) and female (90%). Furthermore, 70% of participants were classified either as overweight, obese, or extremely obese, showing that wellness programs aimed at improving weight loss through nutrition and activity were relevant for this population. Although the purpose of this study was not aimed at weight loss per se, healthy eating and nutrition are known contributors to a healthy weight. The five participants who did not self-report study compliance were all classified as extremely obese. A second statistical analysis was completed on the compliant participants. Interestingly, the AHA MLC score was still not statistically significant even after the non-compliant group was removed from the analysis (p=0.051).

Consistent with previous research, the study found that workplace wellness can positively impact employee health behaviors [21,22,23]. This DNP project’s contribution to the literature was an example of a workplace wellness program delivered in a non-traditional style to sedentary university faculty employees. However, the best type of WWP in this setting will still need additional investigation and planning. The project provided information on the effects of a workplace wellness program on faculty health behaviors. This was important because as health educators, nursing faculty should have opportunities and resources to promote personal health. This project also depicted faculty health characteristics like weight, body mass index, physical activity levels, and basic eating habits. Although the final heart score change was not statistically significant, several areas of improvement were seen in various participant health behaviors, including increased weekly activity and daily fruit consumption. These results were consistent with the previous WWP studies by [20,21]. Moreover, this project provided detailed employee interest information for facility future wellness adventures. Employers might be inspired to invest in workplace wellness programs if they view the investment as beneficial. As stated previously by [22], successful WWP needs leadership involvement, including policies that promote a culture of health. The sustainability plan of establishing a workplace wellness committee, including a human resource person, could improve long-term wellness opportunities for the university. Workplace wellness programs have been linked to positive outcomes, but the question then becomes which program is the best fit for various facilities. This question should be best answered individually by organizations. Similar to the study by [24,25,26], the internetbased WWP approach was doable by most participants. Embracing innovative approaches to wellness that encourage employee input may have improved the chances of successful wellness program implementation and sustainability.

Strengths and Limitations

Several limitations were related to the sample. First, a sample of 20 participants is considered small (Faber & Fonseca, 2014).

Secondly, the project participants were from a satellite university campus concentrated in a Southern region, with the majority of participants being Caucasian and female. Therefore, the study group may not be reflective of the larger population and may limit generalizability. Another limitation of the project was the time of year that it was implemented. This project took place during the fall and ended the week after the Thanksgiving holiday. Participants may have found it challenging to maintain healthy eating habits during a holiday known for eating in abundance. The main strength of the project as it provided the needs assessment and employee interest of a specific facility. This site-specific comprehensive exploration could be used to develop current and future university health practices. Additionally, the recommendation of developing a wellness committee could improve the future health of employees.

Future studies should target more generalizable samples from various regions of the United States. Research focusing on WWP intervention time length, specific program measurement tools, and various seasonal influences would also be beneficial. Finally, specific studies evaluating types of wellness programs yielding effective for university faculty will also be needed.

Discussion and Conclusion

The findings of this study suggested that workplace wellness programs can positively impact faculty health behaviors. Seventyfive percent of the study participants acknowledged that a onceweekly time commitment to wellness activities was both acceptable and sustainable. While the total participants’ group findings were not statistically significant, the author notes that the small sample size and further lack of compliance by some subjects may have impacted the outcomes. A larger sample would have yielded a more reliable result. Workplace wellness programs benefit both employees and employers by improving worker health. More research needs to be conducted to determine if workplace wellness programs could be used to halt the progression of NCDs in an increasingly sedentary world.

References

- World Health Organization (2017) Non-communicable diseases. Retrieved from World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization 2014) United States of America. Retrieved from Non Communicable Diseases Country Profile.

- World Health Organization (2009) The WHO guide to identifying the economic consequences of disease and injury. Retrieved from Cost-Effectiveness and Strategic Planning.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016b) Workplace health resources.

- American Heart Association (2015b) The price of inactivity.

- Popkin B, Adair L, Ng S (2012) Now and then: the global nutrition transition: the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutrition Review 70(1): 3-21.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016a) Preventing a leading risk for death, disease, and injury at a glance 2016. Retrieved from Excessive Alcohol Use.

- American Heart Association (2015a) The case for the workplace health.

- Fonarow G, Calitz C, Arena R, Baase C, Isaac F, Lloyd-Jones D, et al (2015) Workplace wellness recognition for optimizing workplace health. Circulation 131(20): e480-e497.

- Alkhatib A (2013) Sedentary risk factors across genders and job roles within a university campus workplace: A preliminary study. Journal of Occupational Health 55(3): 218-224.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2006) The essentials of doctoral education for advanced nursing practice.

- Alliance for a Healthier Generation (2015) Employee wellness interest survey.

- Alliance for a Healthier Generation (2016) Assess your program. Retrieved from Alliance for a Healthier Generation.

- American Heart Association (2017c) My life check- life's simple 7.

- org (2016) Employee wellness interest survey.

- American Heart Association (2017a) Heart-health risk assessment from the American HeartAssociation.

- Healthier Generation (2013) Employee wellness toolkit.

- American Heart Association (2017b) Workplace health solutions.

- Chiuve S, Cook N, Shay C, Rexrode K, Albert C, et al. (2014) Lifestyle-based prediction model for the prevention of CVD: The healthy heart score. Journal of American Heart Association 3(6): e000954.

- Butler C, Clark R, Burlin T, Castillo J, Racette O (2015) Physical activity for campus employees: A university worksite wellness program. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 12(4): 470-476.

- MacKinnon D, Ellio D, Thoemmes F, Kuehl K, Moe E, et al. (2010) Long-term effects of a worksite health promotion program for firefighters. American Journal of Health Behaviors 34(6): 695-706.

- Elia J, Rose M (2016) Do workplace wellness programs work? Plans and Trusts 34(5): 12-17.

- Siegel J, Prelip M, Erausquin J, Kim S (2010) A worksite obesity intervention: Results from a group-randomized trial. American Journal of Public Health 100(2): 327-333.

- Quyen G, Chen T, Magnussen C, To K (2013) Workplace physical activity interventions: A systematic review. American Journal of Health Promotion 27(6): e113-e123.

- Faber J, Fonseca LM (2014) How sample size influences research outcomes. Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics 19(4): 27-29.

- Human Kinetics Journal (2015) About JPAH.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...