Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1725

Review Article(ISSN: 2641-1725)

Russian Leaders and their Foreign Doctors: A Historical Review Volume 4 - Issue 1

B Petrikovsky*, Y Nemova and E Petrikovsky

- NY Institute of Technology, USA

Received: November 09, 2019; Published: November 19, 2019

*Corresponding author: Boris Petrikovsky, MD, PhD, NY Institute of Technology, 55 Forest Row, Great Neck, NY 11024, USA

DOI: 10.32474/LOJMS.2019.04.000178

Introduction

Russian medicine had its zenith at the beginning of the 20th

century when two Russian scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize;

Ivan Pavlov (1904) for his work on the physiology of digestion, and

Ilya Metchnikoff (1908) for his work on phagocytosis. In the late

19th century, Professor Sergey Botkin was a physician who served

the Czar’s family and oversaw their various ailments. Having

replaced K.K. Gaartman, a German physician who was deemed

insufficiently versed in internal diseases, Professor Botkin served

as the royal physician to the Empress Maria Alexandrovna from

1870 to 1889 [1]. Professor Botkin was meticulous in conducting

thorough examinations including skin temperature levels, pulse,

cough intensity, physical strength, auscultation of the lungs, density

and tenderness of the liver and spleen, the position of the kidneys,

the thickness of subcutaneous fat, hearing condition, swelling of

the legs, etc. Furthermore, in analyzing the content of the royal

spittoon, its structure and the volume of sputum, Botkin used a

microscope at a time when laboratory diagnostics as a specialty was

just beginning to emerge. Botkin calculated the volume of urinary

sediments as well as its gravity, carried out chemical reactions for

protein identification, and searched the sputum for elastic fibers,

which were a known sign of lung tissue destruction.1 After studying

abroad under Rudolf Virchow in Würzburg, Ernst Felix Hoppe

and Ludwig Traube in Berlin, Karl Ludwig in Vienna, and Claude

Bernard in Paris, Professor Botkin established a laboratory in his

clinic for the first time in Russia [2].

Nikolay Sklifosovsky was another prominent pre-revolutionary

physician who facilitated the widespread use of anesthesia in

surgery, initiated abdominal surgery in Russia, and performed the

first successful laparotomy. Sklifosovsky proposed the “Russian

castle,” which was a novel method of connecting tubular bones, and

developed a technique for removing bladder stones, among others

[3]. After he graduated from the Imperial Moscow University in

1859, Sklifosovsky was granted the opportunity to broaden and

enhance his medical and surgical knowledge by visiting the best

clinics of Germany, France, and Great Britain [3].

After the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, centralization, forced

collectivization, international isolation, and restrictions on travel

to Western Europe, medical sciences suffered from a lack of

funding and a lack of government prioritization. The new Soviet

government radically transformed medical care in Russia to a

system that formally focused on equal access to health care and

preventive medicine. The Soviet state declared that if their society

was to function effectively, it must have healthy members. Because

the state believed that health care is a right rather than a privilege,

medical care should be free and available to all. Additionally, the

government heavily prioritized preventive medicine as they

believed that it was the foreground of all health activities. In order

to implement these new approaches and to ensure health can be

planned on a large scale, the government took control of all health

activities and instituted the People’s Commissariats of Health.

Hence, medicine became a public function of the state [4].

On November 13, 1917, just days after the revolution, the

government declared that the previous Czarist government,

representing the capitalists and the landowners, failed the workers

and all poor citizens. Because of this perceived abuse, the Soviet

government promised to provide insurance for all wage workers

and poor citizens covering all disabilities such as illness, injury,

old age, maternity, etc. In implementing the state’s desired focus of

preventive medicine, in 1921, the aforementioned Commissariat of

Health was tasked with monitoring the health of all people from the

day they were born till their demise. Because the Soviet Union was

devised to represent one great entity built in complete harmony,

medical services became a function of the collective, i.e., if one

individual is harmed, then all of society is harmed. In short, the new

Russian state was an equal, collective society. This philosophy was

put into practice first in health resorts, establishments once only

available to the wealthy and privileged, now open to and handed

back to the people [4].

Making healthcare free and accessible to all in Russia did not

occur smoothly and was plagued with deficiencies. Leo Trotsky, one of the founders of Bolshevism (communist expansion) in Russia,

banned private practices, arrested, and threatened a number of

prominent Russian physicians with the death penalty. All private

hospitals built by philanthropists, such as Abrikosov and Morozov,

were declared government property. There were serious shortages

of physicians, medical personnel, and medical facilities [4]. The

Soviet state was somewhat successful in granting medical care to

its people regardless of class; however, the quality of the services

suffered. Due to limited investment in medical research and

technology, Soviet medicine fell far behind its Western counterparts.

As a result of the many restrictions placed on physicians, medical

education took a hit as doctors had no access to medical progress

outside Russia and medical students were unable to study abroad.

Unlike Czars Alexander II and III, who employed Professor Botkin

as their personal physician [5-11], the leaders of the Soviet Union

could not easily secure a Russian physician for specific ailments

requiring specialized expertise. They had isolated Russian society

from the West by outlawing Western influences, including advances

in medicine. The leaders of the Soviet Union were stuck with the

equal health system that was accessible to all citizens, and were not

satisfied, as they felt that given their high-ranking position, they

merited better [12-15].

Consequently, the Soviet government created two systems of

medical care; one for regular citizens, and one for highly privileged,

high-ranking government officials, essentially creating an upper

class with regards to access to high-quality health care. Top

government officials, including Politburo members, were allowed

to use top foreign physicians who were invited to Russia to provide

consultative and surgical services. Starting with Vladimir Lenin,

Soviet leaders used prominent Western specialists, eluding the

equal system of which they were the creators. Although communist

philosophy endeavors to treat all working people as equals, the

leaders’ families were provided with the best health care available

around the globe, a service that was unattainable for the common

man.

Below, please find a pictorial essay of Russian leaders and

dignitaries (on the left) and their foreign doctors (on the right).

VIP Patients

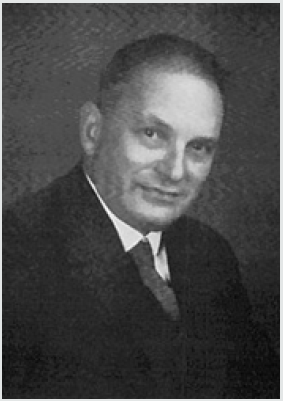

Vladimir I Lenin (Ulyanov) (1870-1924) was a pivotal figure

in world politics in the early part of the 20th century. He was one

of the founders of the Russian Bolshevik (communist) party and

became the first head of the Soviet government. An atheist and true

believer in the class theory of Karl Marx, Lenin stood as an icon of

communism. In an assassination attempt on Lenin that took place

on August 30, 1918, he was wounded and operated on.

Later he developed a right hemiparesis, including both the

arm and the leg. During a period of slow recovery, he resumed his

activities at home. He wrote articles, or rather, dictated them to his

wife or secretary. Lenin asked Stalin for potassium cyanide, saying,

“if I lose my speech, I’ll take poison.” According to Fotieva, Lenin’s

secretary, in December 1922, Lenin secretly sent his secretary to

Stalin for poison, but was apparently refused after Stalin consulted

with Foerster, Lenin’s attending physician, who confirmed Lenin’s

sister’s impression of the unpredictability of his illness.

Felix Klemperer, Professor of Medicine, Berlin, Germany.

On April 7, 1922, Lenin wrote to Ordzhonikidze complaining of

continuing headaches. Dr. Felix Klemperer suggested the symptoms

might indicate lead poisoning caused by the bullets remaining in

Lenin’s body since the attempt on his life of August 30, 1918.

His colleague disagreed with him; nonetheless 1 of 2 bullets was

surgically removed by professor Moritz Borchardt from Berlin [16-

22] (Figure 1).

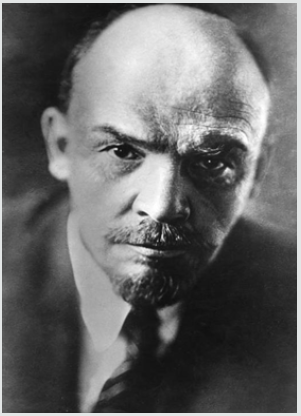

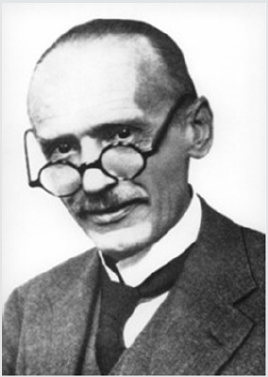

Otfrid Foerster (1873-1941) was a student of Carl Wernicke and a renowned German neurologist. Foerster developed several procedures, including electrocorticography for the identification of epileptic foci. He also described the atonic-astatic type of cerebral palsy, which bears his name. His reputation as a neurologist, as well as his speaking knowledge of Russian, made him a natural choice as one of Lenin’s consultants (Figures 2 & 3).

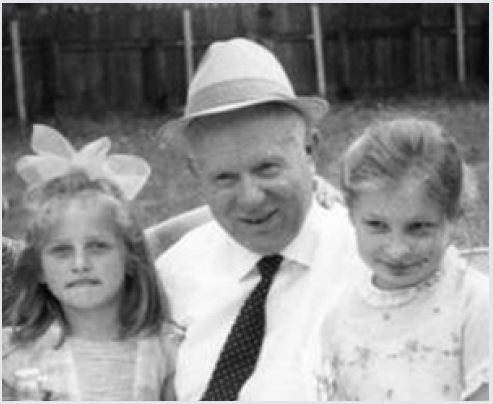

Elena Khrushcheva (1937—1972), N. Khrushchev’s daughter, who suffered from Lupus with renal involvement (Figure 4).

A. McGehee Harvey (1911-1998) was born in Little Rock,

Arkansas (USA). He developed the first research-based school of

medicine in the United States at the Johns Hopkins Hospital (Figure

5). “He was truly one of the greatest physicians of the 20th century”

said one of his students, Dr. Eugene Braunwald, at the Hersey

Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Harvey’s

application of scientific methods and clinical problem-solving got

him called upon for difficult cases around the world. In 1969, Dr.

Harvey and his wife, Dr. Elizabeth Treide Harvey, went to the Soviet

Union to treat the daughter of Nikita S. Khrushchev, the former

Soviet leader, for lupus, which was one of his specialties.

M. Suslov, Politburo member

He suffered from Angina (Figure 6)

M. Suslov’s wife

She suffered from poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

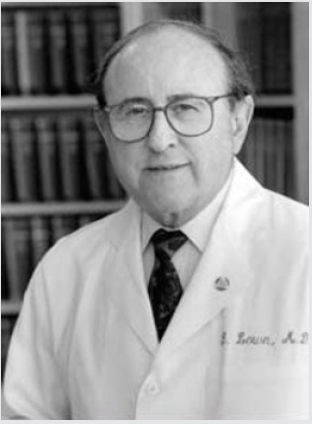

Bernard Lown (June 7, 1921) was born in Lithuania. He

emigrated to the United States at the age of 14. Dr. Lown is the

original developer of the DC defibrillator and the cardioverter

(Figure 7). In 1985, Lown accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf

of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War,

an organization he co-founded with Soviet cardiologist, Yevgeny

Chazov, who later became the Minister of Health of the USSR.

Bernard Lown was once asked to see Suslov’s wife in the Kremlin

Hospital; it was one of the few cases where a renowned foreign

doctor was invited to visit the Kremlin Hospital. Suslov expressed

his gratitude for Lown’s work but avoided meeting Lown in person

because he was a representative of an “imperialistic” country.

Mstislav Keldysh, a nuclear scientist and President of the Soviet

Academy of Science (1961-1975).

He was a chain smoker and suffered from chronic vascular

insufficiency (Figure 8).

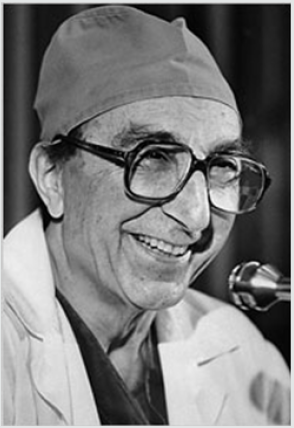

M. DeBakey (1908-2008) was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana

(USA). He pioneered the use of Dacron grafts to replace or repair

blood vessels (Figure 9). In 1958, Dr. DeBakey performed the first

successful patch-graft angioplasty. The patch widened the artery,

so that when it closed, the channel of the artery returned to normal

size. He also never let politics come between him and delivering

needed care. In the middle of the Cold War he became a respected

physician in the Soviet Union, operating on Mstislav Keldysh, the

President of the Soviet Academy of Scientists during the 1970’s.

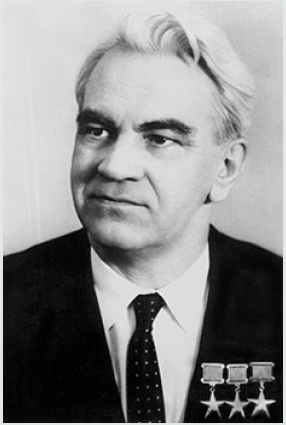

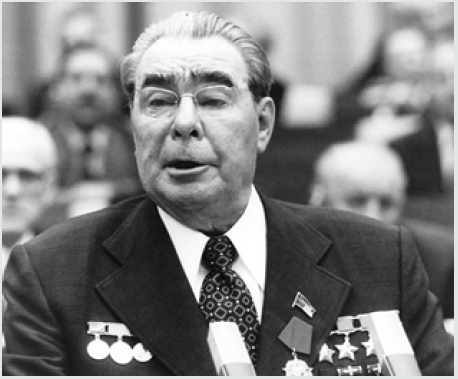

Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary (1964-1982)

Suffered from speech impairment and dental issues (Figure 10)

Jacobs, DDS and Oral Surgeon

Bonn, Germany

Yuri Andropov, KGB Chief, General Secretary (1982-1984)

(Figure 11)

Suffered from chronic renal insufficiency

A. Rubin, Cornell University. Dr. Rubin was the first

nephrologist in New York to provide kidney dialysis (1956) and renal transplantation (1963) (Figure 12). To implement his

comprehensive, integrative approach to kidney disease, he created

the Rogosin Institute. Dr. Rubin* initiated and shepherded the

Institute’s major research programs in renal disease, diabetes, lipid

disorders, and cancer. By the summer of 1983, Andropov’s health

was giving rise to serious concern. He found it hard to move, signs of

general debility increased. Yevgeny Chazov, the Health Minister and

Chief of the 4th Main Administration, which included the Kremlin

clinic, recalled that Professor A. Rubin, a noted American specialist,

was invited to Moscow. Rubin carried out a thorough examination

and concurred with treatment the Soviet physicians had been

giving. His diagnosis was generally encouraging and reassuring.

Konstantin Chernenko, General Secretary (1984-1985) (Figure 13)

A former chain smoker, he suffered from chronic obstructive

lung disease, and emphysema

Raisa, Gorbacheva, wife of Mikhail Gorbachev, Soviet President,

suffered from leukemia (1932-1999) (Figure 14)

Thomas Büchner was born in Berlin. He graduated from the Albert-Ludwig University in Freiburg (Figure 15). In 1971, his publication “Inflammatory cells in Blood and Tissues” was awarded the Theodor-Frerich Prize from the German Society for Internal Medicine, followed by a professorship in Internal Medicine and Hematology at Wilhelms University in Münster. He managed a Laboratory of Special Hematology at the Medical Clinic of Münster University. Raisa Gorbacheva travelled with her husband and daughter to Münster in Germany for treatment at the medical clinic of the Münster University Hospital. She received treatment for two months under the supervision of Professor Thomas Büechner, a leading hematologist.

In 2007, in memory of his wife, Mikhail Gorbachev, in cooperation with Pavlov University, funded the construction of the Raisa Gorbacheva memorial institute for Hematology and Transplantation, which started to work with the support of Professor Büchner.

Boris Yeltsin, Russian President (1991-1999)

Suffered from chronic heart disease and multiple heart attacks.

Later, due to chronic alcoholism, B. Yeltsin suffered from an unspecified neurological disorder that affected his sense of balance,

causing him to wobble as if in a drunken state.

Dr. M. DeBakey

In addition to providing Mstislav Keldysh with medical care, Dr.

DeBakey worked extensively on treating heart patients.

DeBakey operated on more than 60,000 patients, including

several heads of state. DeBakey and a team of American

cardiothoracic surgeons supervised a quintuple bypass surgery

performed by Russian surgeons on Russian President Boris Yeltsin

in 1996 (Figure 16).

Dr. Michael Staal was born in Amsterdam on August 17, 1949 (Figure 17). He wrote many articles on neuromodulation and received a professorship for neuromodulation in 2003. He was chairman of the Benelux Neuromodulation Society (BNS) chapter of the INS from 2009-14. He successfully organized several symposia on motor cortex stimulation. He had been secretly flown to Moscow to operate on Yeltsin; the goal of the operation was pain reduction.

References

- Shergill SS, Bays PM, Frith CD, Wolpert DM (2003) Two Eyes for an Eye: The Neuroscience of Force Escalation. Science 301(5630): 187-187.

- Kilteni K, Ehrsson HH (2017) Body ownership determines the attenuation of self-generated tactile sensations. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(31): 8426-8431.

- Blakemore SJ, Wolpert DM, Frith CD (1998) Central cancellation of self-produced tickle sensation. Nat Neurosci 1(7): 635-640.

- Ferri F, Chiarelli AM, Merla A, Gallese V, Costantini M (2013) The body beyond the body: expectation of a sensory event is enough to induce ownership over a fake hand. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 280(1765): 20131140.

- Ferri F, Costantini M, Salone A, Di Iorio G, Martinotti G, et al. (2014) Upcoming tactile events and body ownership in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 152(1): 51-57.

- Guterstam A, Zeberg H, Özçiftci VM, Ehrsson HH (2016) The magnetic touch illusion: A perceptual correlate of visuo-tactile integration in peripersonal space. Cognition 155: 44-56.

- Guterstam A, Szczotka J, Zeberg H, Ehrsson HH (2018) Tool use changes the spatial extension of the magnetic touch illusion. J Exp Psychol Gen 147(2): 298-303.

- Ferri F, Ambrosini E, Pinti P, Merla A, Costantini M (2017) The role of expectation in multisensory body representation–neural evidence. Eur J Neurosci 46(3): 1897-1905.

- Makin TR, Holmes NP, Ehrsson HH (2008) On the other hand: dummy hands and peripersonal space. Behav Brain Res 191(1): 1-10.

- Tsakiris M (2010) My body in the brain: a neurocognitive model of body-ownership. Neuropsychologia 48(3): 703-712.

- Botvinick M, Cohen J (1998) Rubber hands “feel” touch that eyes see. Nature 391: 756.

- Skopec R (2019) Quantum Resourrection: Quantum Algorithm With Complex Conjugation Reverses Phases Of The Wave Function Components. Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery.

- Skopec R (2018) Evolution Continues with Quantum Biology and Artificial Intelligence. ARC Journal of Immunology and Vaccines 3(2): 15-23.

- Skopec R (2019) Naphazoline nitrate treat the frey effect of microwave and other sonic weapon’s damages in human’s internal, organs. Virology: Research & Reviews (1): 1-5.

- Skopec R (2019) Negative Health Effects of the International Space Station. Stem Cell Research International 3(2): 1-6.

- Skopec R (2019) Fifth Dark Force Completely Change Our Understanding of the Universe. Research Journal of Nanoscience and Engineering 3(2): 39-47.

- Skopec R (2019) Darwin’s Theorem Revised: Survival of the Careerist. Advancements in Cardiovascular Research 1(5): 89-93.

- Skopec R (2019) New Psychological Weapons Make Targets Hallucinate. Journal Of Neuropsychiatry And Neurodisorders 1(1): 1-6.

- Skopec R (2019) The Transfiguration with Self-Phase Modulation Effect of Entanglement in a Plasmatic Moving Frame. Current Trends in Biotechnology and Biochemistry.

- Skopec R (2019) Quantum Entanglement Entropy as Karma Lead to New Scientific Revolution. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences Technology 1: 1

- Skopec R Quantum Entanglement Entropy Produces Energy by Info-Entropy Fields Forces, Modern Approaches on Material Science.

- Ehrsson HH (2012) The Concept of Body Ownership and its Relation to Multisensory Integration. In: Stein B, editor. The Handbook of Multisensory Processes. Boston, USA.

- Moseley GL, Gallace A, Spence C (2012) Bodily illusions in health and disease: Physiological and clinical perspectives and the concept of a cortical ‘body matrix.’ Neurosci Biobehav Rev 36(1): 34-46.

- Blanke O, Slater M, Serino A (2015) Behavioral, Neural, and Computational Principles of Bodily Self-Consciousness. Neuron 88(1): 145-166.

- Ferri F, Costantini M (2016) Commentary: The magnetic touch illusion: A perceptual correlate of visuo-tactile integration in peripersonal space. Front Hum Neurosci 10: 492.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...