Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1725

Case Report(ISSN: 2641-1725)

Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Unusual Cause of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding A Case Report and Literature Review Volume 4 - Issue 4

Ali Hussain1*, Hira Yousuf1, Mohamed Shaban1, Sadaf Cheema1 and Akbar Mahmood2

- 1Pinderfields General Hospital the Mid Yorkshire NHS Trust, UK

- 2ultan Qaboos University, Oman

Received: January 28, 2020; Published: February 04, 2020

*Corresponding author: Ali Hussain, Pinderfields General Hospital the Mid Yorkshire NHS Trust, UK

DOI: 10.32474/LOJMS.2020.04.000192

Introduction

Annually, bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract occurs in approximately 100 per 100000 people [1-3] and neoplasm accounts for (1-4%) of the cases. Renal cell carcinoma constitutes 3% of all adult malignancies and at the time of diagnosis, almost (25-30%) of patients have metastases. Gastrointestinal bleeding from renal cell carcinoma metastases is an uncommon and underrecognized manifestation of this disease. In this case report, we describe a case of upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the second part of duodenum.

Case Presentation

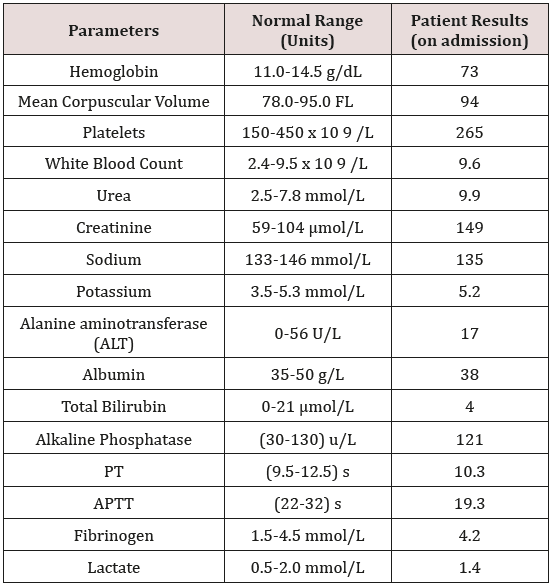

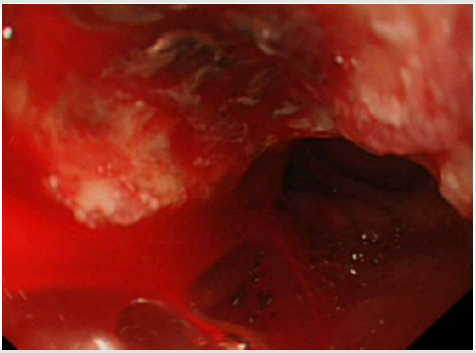

A 76 years old male known case of renal cell carcinoma status post nephrectomy and on ongoing chemotherapeutic agents was presented to the emergency department with a history of passing a single episode of black tarry and foul-smelling stools overnight. The patient denied any history of epigastric pain, hematemesis, dizziness, syncope or shortness of breath. There is no history of the use of Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), anticoagulants and steroids. The patient is a lifelong non-smoker and drinks 3 pints of alcohol per week. On admission, his BP was 106/56, heart rate was 75bpm, and respiratory rate was 20. He was alert and the oxygen saturation on room air was 97%. His NEWS score was 2. On general physical examination, he appeared paler but there weren’t any clinical stigmata of cirrhosis of liver. The rest of the general physical exam was unremarkable. The Abdominal examination showed soft non-tender abdomen with no hepatosplenomegaly, a healed scar of a previous nephrectomy was present. The Cardiovascular and Respiratory exams were unremarkable. Patient Glasgow Blatchford’s score was 11. His heamoglobin was 73 with MCV of 94.8 and a platelets count of 265, his e-GFR was 39 and coagulation profile was normal PT of 10.3 and APTT of 19.3. Additionally, his liver function test was normal as shown in Table 1 below. The patient was counseled for blood transfusion and an urgent upper GI endoscopy was planned. A blood transfusion was given and he underwent endoscopy. The endoscopy (Figure 1) revealed an extension of cancer into the duodenum with slow oozing of blood, which was not amenable to endoscopic intervention. It was planned that the patient shall undergo embolization of the vessel, but it was not performed as the patient stopped bleeding. Furthermore, Radiotherapy was not an option to stop the bleeding. Palliative chemotherapy was started for the patient after liaison with the Oncology team.

Figure 1: Endoscopy shows that malignant lesion protruding in the wall of duodenum with oozing of blood. Blood could be seen in the lumen.

Discussion

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is a medical emergency associated with a substantial overall mortality rate of 10% in the UK. Bleeding is common in advanced cancer, occurring in up to 10% of patients with varying etiologies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, anticoagulants, surgery, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and qualitative and quantitative defects in platelets. Oozing and chronic blood losses are frequently associated with malignant lesions however, are uncommon and account for less than 5% of acute bleeding episodes. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a great mimicker; it behaves unpredictably and has a diverse range of clinical manifestations. Patients often present insidiously with vague abdominal symptoms the classic triad of hematuria, loin pain and abdominal mass is found in only (4-17%) [4,5]. At the time of diagnosis, (25-30%) of patients are found to have metastases. Furthermore, during the illness, 30–50% of patients with local disease will develop metastases [6]. Rarely, metastases develop in the pancreas and small intestine in RCC but can present as gastrointestinal bleeding. [7,8] Metastatic tumor involving the small bowel most commonly arises from melanoma, bronchus or breast cancer or trans coelomic spread from intra-abdominal malignancy. Small bowel metastases from renal cell carcinoma are rare. Autopsy Studies suggest only 2% of all tumors metastasize to the small intestine RCC make up 7.1% of these lesions [9]. According to case series published by Graham, [10] only 4% of RCC metastasize to the small intestine, while a 50-year review of Mayo Clinic data found only 3 cases of small intestinal metastasis in RCC, which did not include cases of direct tumor extension [11]. Of all intestinal segments involved, RCC metastasis to the duodenum occurs least frequently [12]. Duodenal involvement by renal cell carcinoma may be by either direct spread of local recurrence or from lymphatic or haematogenous spread. The overwhelming majority of tumors metastasizing to the duodenum arises from the right kidney given its anatomic proximity [13], and of the few published reports, most commonly involves the periampullary region, followed by the duodenal bulb. These usually manifest as gastrointestinal bleeding, although cases of small bowel intussusception are described [14,15]. Direct invasion of the duodenum from pancreatic metastases is also reported [10]. Our patient represents both presumed direct invasion of duodenum and haematogenous/ lymphatic spread. Bleeding is more commonly encountered in patients already known to have metastatic disease, or as the first symptom of metastatic disease in patients who have previously undergone nephrectomy for RCC [17,18]. Duodenal metastasis commonly present with obstruction, intussusception, tumor necrosis and perforation. However, Gastrointestinal bleeding is least common. Nevertheless, diagnosis is always challenging, as the role of endoscopy is limited in the small bowel. On the other hand, the rate of bleeding from lesion is important to make a diagnosis, as a lesion with a slow rate of bleeding is difficult to detect even on arteriography. To further complex the matter, several bowel tumors like leiomyoma or carcinoid have similar angiographic appearances [19]. Unfortunately, the outcome in metastatic RCC is poor, with 48% 1-year survival and 9% 5-year survival rates. Evidence is lacking in the favor of metastasectomy in RCC [20].

Conclusion

Duodenal metastasis may present as gastrointestinal bleeding either as overt hematemesis or occult bleeding in the form of melena. Due to its rarity, even in cancer patients, small intestinal metastasis is often not suspected as a cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. In this report, we hope to alert clinicians to always consider the possibility of intestinal metastasis, or local small bowel invasion, irrespective of nephrectomy or the time of nephrectomy as a cause for gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with a history of RCC.

References

- Ghassemi KA, Jensen DM (2013) Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 15(7):

- Siau K, Chapman W, Sharma N, Tripathi D, Iqbal T, et al. (2017) Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: an update for the general physician. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 47(3): 218-230.

- British Society of Gastroenterology (2007) UK comparative audit of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and the use of blood.

- Waters WB, Richie JP (1979) Aggressive surgical approach to renal cell carcinoma: Review of 130 cases. J Urol 122(3): 306-309.

- Griffiths LH, Thackray AC (1949) Parenchymal carcinoma of the kidney. Br J Urol 21(2): 128-151.

- Pavlakis GM, Sakorafas GH (2004) Anagnostopoulos GK: Intestinal metastases from renal cell carcinoma: A rare cause of intestinal obstruction and bleeding. Mt Sinai J Med 71(2): 127-130.

- Black JA, Mendelson RM (1995) Duodenal haemorrhage resulting from renal cell carcinoma metastases. Australas Radiol 39(4): 396-398.

- Chang WT, Chai CY, Lee KT (2004) Unusual upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to late metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 20(3): 137-141.

- Willis RA (1973) Secondary tumours of the intestines. The spread oftumours in the human body Volume 21. 3rd Butterworth & Co., Ltd, London, pp. 209-213.

- Graham AP (1947) Malignancy of the kidney: survey of 195 cases. J Urol 58(1): 10-21.

- Low ED, Frenkel VJ, Manley PN, Ford SN, Kerr JW, et al. (1989) Embolicmesenteric infarction: A unique manifestation of renal cell carcinoma. Surgery 106(5): 925-927.

- Short TP, Thomas E, Joshi PN, Martin A, Mullins R (1993) Occult gastrointestinal bleeding in renal cell carcinoma: value of endoscopic evaluation. Am J Gastroenterol 88(2): 300-302.

- Deguchi R, Takagi A, Igarashi M, Shirai T, Shiba T, et al. (2000) A case of ileocolic intussusceptionfrom renal cell carcinoma. Endoscopy 32(8): 658-660.

- Haynes IG, Wolverson RL, O'Brien JM (1986) Small bowel intussusception due to metastatic renal carcinoma. Br J Urol 58(4): 460.

- Perez VM, Huang GJ, Musselman PW, Chung D (1998) Lower gastrointestinal bleeding as the initial presenting symptom of renal cell carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 93(11): 2293-2294.

- Ramirez Fabian M, Vicente Aldea MT, Ambroj Navarro C, Rodriguez Bazalo JM, Ucar Terren A, et al. (1998) Rectal hemorrhage as a first sign of renal cell adenocarcinoma. Actas Urol Esp 22(7): 599-601.

- Ohmura Y, Ohta T, Doihara H, Shimizu N (2000) Local recurrence ofrenal cell carcinoma causing massive gastrointestinal bleeding: a report of two patients who underwent surgical resection. Jpn J Clin Oncol 30(5): 241-245.

- Harish K, Raju SL, Nagaraj HK (2006) Recurrent renal cell carcinoma presenting as gastrointestinal bleed. A case report. Minerva Urol Nefrol 58(1): 87-90.

- JAR Black, RM Mendelson (1995) Duodenal hemorrhage resulting from renal cell Carcinoma metastases Australasian Radiology 39(4): 396-398.

- Ohmura Y, Ohta T, Doihara H, Shimizu N (2000) Local recurrence of renal cell carcinoma causing massive gastrointestinal bleeding: a report of two patients who underwent surgical resection. Jpn J Clin Oncol 30(5): 241-245.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...