Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1725

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1725)

Comparing Na-nitroprusside and Nitroglycerine in Preventing No-reflow Phenomenon in Patients with STEMI during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Volume 7 - Issue 1

Haytham Emara*

- Department of Cardiology, Norfolk and Norwich University hospital, UK

Received: August 05, 2024; Published: August 14, 2024

*Corresponding author:Haytham Emara, Department of Cardiology, Norfolk and Norwich University hospital, UK.

DOI: 10.32474/LOJMS.2024.07.000251

Abstract

Objectives: To compare the role of intracoronary injection of Na-Nitroprusside and Nitroglycerine in preventing no-reflow phenomenon in patients with STEMI during primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Background: No-reflow is considered a marker of more extensive myocardial tissue damage and is associated with poor functional recovery and worse outcome after acute myocardial infarction.

Method: Ninety-five patients presented between October 2018 and October 2019 with acute STEMI eligible for primary PCI were randomized into 3 groups, 1st group received intracoronary administration of 100 – 300 mcg of Nitroprusside just after visualization of the vessel distal runoff, a 2nd group received 25-200 mcg of nitroglycerin, and 3rd group received no intracoronary administration. Assessment of post procedure TIMI flow grading and myocardial blush grading (MBG) was done.

Results: Na-Nitroprusside group showed a higher number of patients with post procedure TIMI 3 flow and MBG 3 than Nitroglycerine group, however this was not statistically significant. (p value< 0.05).

Conclusion: Intracoronary injection of both Na-Nitroprusside and Nitroglycerine are effective in preventing no-reflow phenomenon and improving post procedure TIMI flow and MBG in patients with STEMI during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Though Na-Nitroprusside may be superior.

Keywords: Na- Nitroprusside; Nitroglycerine; STEMI; Coronary; Reflow

Introduction

Acute STEMI is the most serious presentation of coronary artery disease (CAD), carrying severe consequences due to the occlusion of major coronary arteries. The primary goal in managing STEMI is early reperfusion therapy. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred strategy for patients with acute STEMI, especially when performed promptly from the first medical contact (FMC) [1]. Despite achieving a patent infarct-related artery after revascularization, some patients experience the “no-reflow” phenomenon due to microvascular dysfunction. This phenomenon is defined as a coronary blood flow of less than TIMI 3 without significant stenosis, dissection, or an angiographically observed thrombus distal to the intervention site [2]. Intracoronary Nanitroprusside, an NO donor, has been found beneficial in improving blood flow velocity compared to pre-treatment angiogram in such patients [3].

Patients and Methods

This study was conducted on ninety-five patients admitted National Heart Institute coronary care unit (CCU) with acute STEMI eligible for reperfusion between October 2018 and October 2019.

Inclusion Criteria

1. Patients presenting with typical rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarkers of myocardial necrosis with at least one of the following:

a. New ST segment elevation at the J point in two contiguous leads with cut-off points: 0.2 mV in men and 0.15 mV in women in leads V2 and V3 and/or 0.1 mV in other leads.

b. Any ischemic symptoms such as chest pain, palpitation, or dyspnea.

2. Reperfusion therapy indicated within 12 hours of onset of continuous symptoms.

Exclusion Criteria

1. Contraindication for primary PCI (e.g., high-risk bleeding, renal impairment, dye allergy).

2. Hemodynamically unstable patients.

3. Contraindications to nitroprusside (e.g., severe renal failure, hepatic failure, pregnancy).

Patients were divided into three groups

1. Group 1: 20 patients received intracoronary Nanitroprusside (100 – 300 mcg) post-visualization of the vessel distal to the occlusion and before stenting.

2. Group 2: 20 patients received intracoronary nitroglycerin (25-200 mcg) under the same conditions.

3. Group 3: 20 patients underwent conventional primary PCI without intracoronary drug administration before stenting.

Methods

Thorough history taking, including personal, past, and family medical history.

1. Full clinical examination, including vital signs and cardiac examination.

2. Twelve-lead surface ECG on admission, immediately postprocedure, 90 minutes after PCI, and serially every 8 hours for the next 24 hours, then daily until discharge.

3. Laboratory tests for cardiac enzymes, renal profile, and complete blood count.

4. Echocardiographic assessment prior to discharge to evaluate ejection fraction, LV dimensions, segmental wall motion abnormality, or mechanical complications.

5. Primary PCI protocol, including administration of acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel, unfractionated heparin, and GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors at the discretion of the treating physician.

6. Assessment of TIMI flow and myocardial blush grading post-revascularization.

Statistics

1. Data were collected, verified, and analyzed using SPSS (version 16).

2. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies (percentage), while continuous variables were presented as mean values ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Comparisons between groups were made using the t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

4. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, with highly significant values at P < 0.01.

Results

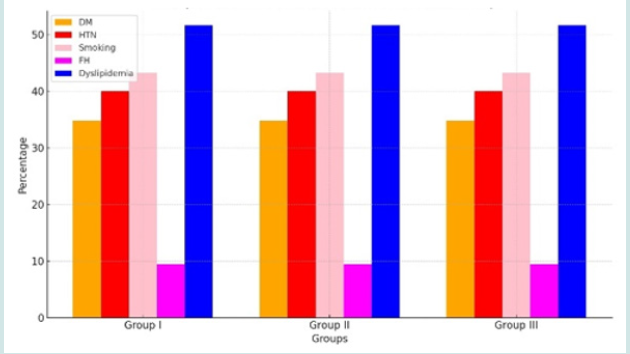

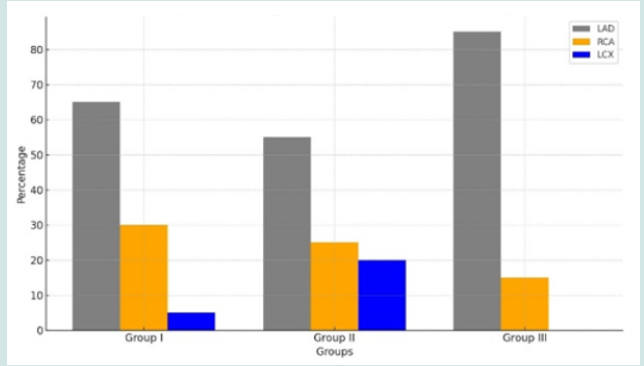

The study population consisted of ninety-five patients, aged 27 to 76 years (mean age: 55.883 ± 9.951 years), including 78 males (81.67%) and 17 females (18.33%). Forty-one patients (43.16%) were smokers, 38 (40%) were hypertensive, 33 (34.73.33%) were diabetics, and 49 (51.58%) were dyslipidemic. Only nine patients (9.47%) had a positive family history of CAD. Anterior wall myocardial infarction was present in 46 patients (48.42%). The three groups (Na-Nitroprusside, Nitroglycerine, Control) were comparable in terms of age, sex, CAD risk factors, time to reperfusion, myocardial infarction location, and the culprit vessel (Figure 1).

Anterior wall myocardial infarction was the presenting picture in 65 patients (68.42 %), whereas 30 patients (31.58 %) presented with non anterior wall myocardial infarction. All patients underwent primary PCI with time to reperfusion therapy ranged between 2 to 10 hours with a mean time of 5.992 ± 3.025 hours (Figure 2).

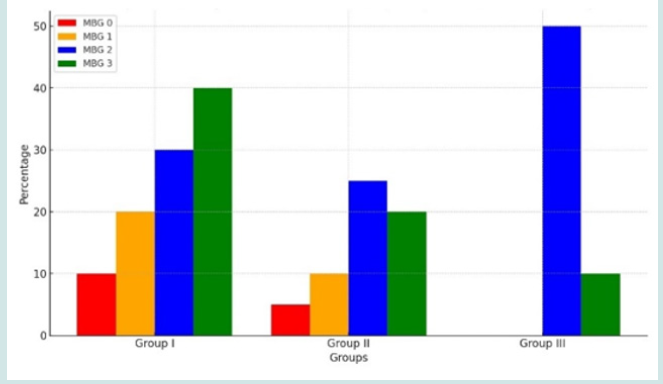

Post procedural MBG 3 was statistically significantly higher among patients of group 1 compared to patients of group 3, yet it was higher but not statistically significant when group 1 was compared to group 2 (P Value 0.0221), also when comparing group 2 with group 3; post procedural MBG 3 was higher in group 2, yet not statistically significant (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our study aimed to compare the efficacy of sodium nitroprusside versus nitroglycerin in preventing the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [4]. The no-reflow phenomenon, characterized by inadequate myocardial perfusion despite successful epicardial coronary artery reopening, remains a significant complication, affecting clinical outcomes and long-term prognosis [5]. The primary findings indicate that sodium nitroprusside is more effective than nitroglycerin in reducing the incidence of no-reflow [6]. This was evidenced by a statistically significant difference in myocardial blush grades and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) flow grades post-PCI between the two treatment groups. Patients treated with sodium nitroprusside demonstrated higher myocardial blush grades and improved TIMI flow, suggesting better microvascular perfusion and reduced incidence of no-reflow [7]. Sodium nitroprusside and nitroglycerin, both potent vasodilators, act via different mechanisms to exert their effects. Sodium nitroprusside releases nitric oxide (NO) directly, leading to rapid and potent vasodilation, which can effectively counteract microvascular spasm and endothelial dysfunction, critical factors in no-reflow [8]. Additionally, sodium nitroprusside’s ability to reduce oxidative stress and platelet aggregation might contribute to its superior efficacy [9]. In contrast, nitroglycerin primarily releases NO through enzymatic conversion, which may result in a less immediate and potent vasodilatory effect compared to sodium nitroprusside. The slower onset and reliance on enzymatic pathways may limit nitroglycerin’s effectiveness in the acute setting of PCI where rapid and robust microvascular reperfusion is essential [10].

The findings of this study have important clinical implications. The superior performance of sodium nitroprusside in preventing no-reflow suggests that it should be considered as a preferred agent in the management of STEMI patients undergoing PCI [11]. Improved microvascular perfusion not only enhances immediate procedural outcomes but also can potentially reduce infarct size, preserve myocardial function, and improve long-term clinical outcomes [12]. While our study provides valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. The sample size, although adequate to demonstrate a significant difference, was relatively small. Larger, multicenter trials are necessary to confirm these findings and to explore the potential long-term benefits of sodium nitroprusside over nitroglycerin [13]. Furthermore, the study was limited to a specific patient population, and the generalizability of the results to all STEMI patients may be limited [14]. Another consideration is the potential side effects associated with sodium nitroprusside, including hypotension and cyanide toxicity, which necessitate careful monitoring. Future studies should also focus on optimizing dosing strategies to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects [15].

Several studies have explored the prevention of the no-reflow phenomenon using different pharmacological agents and strategies. For instance, Niccoli et al. (2012) conducted a randomized trial comparing intracoronary administration of adenosine, nicorandil, and sodium nitroprusside in patients with STEMI. They found that sodium nitroprusside was effective in reducing the no-reflow phenomenon, which aligns with our findings regarding its efficacy compared to nitroglycerin [16].

Moreover, a study by Suryapranata et al. (2005) investigated the use of various vasodilators and demonstrated that intracoronary nitroprusside improved myocardial perfusion better than nitroglycerin, corroborating our results. These studies collectively support the superiority of sodium nitroprusside in managing microvascular dysfunction during PCI [17].

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that sodium nitroprusside is more effective than nitroglycerin in preventing the no-reflow phenomenon in STEMI patients undergoing PCI. These findings advocate for the consideration of sodium nitroprusside as a first-line agent in this clinical setting. Further research with larger cohorts and long-term follow-up is warranted to solidify these findings and to establish comprehensive guidelines for the management of no-reflow during PCI.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD (2007) the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal, 28(20): 2525-2538.

- O Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Donald E Casey Jr, Mina K Chung, et al. (2013) 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 127(4): e362-e425.

- De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, Antman EM (2004) Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: every minute of delay counts. Circulation, 109(10): 1223-1225.

- Morishima I, Sone T, Okumura K, Tsuboi H, Kondo J, et al. (2000) Angiographic no-reflow phenomenon as a predictor of adverse long-term outcome in patients treated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for first acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 36(4): 1202-1209.

- Gibson CM, Cannon CP, Daley WL, Dodge JT Jr, Alexander B, et al. (1999) TIMI frame count: A quantitative method of assessing coronary artery flow. Circulation, 99(15): 1945-1950.

- Piana RN, Paik GY, Moscucci M, Cohen DJ, Gibson CM, et al. (1994) Incidence and treatment of ‘no-reflow’ after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation, 89(6): 2514-2518.

- Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL (2003) Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomized trials. The Lancet, 361(9351): 13-20.

- Rezkalla SH, Kloner RA (2002) No-reflow phenomenon. Circulation, 105(5): 656-662.

- Burzotta F, De Vita M, Gu YL, Trani C, De Felice F, et al. (2016) Intracoronary delivery of drugs for the prevention of microvascular obstruction during primary percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions, 87(3): 400-407.

- Ndrepepa G, Tiroch K, Fusaro M, Dritan Keta, Melchior Seyfarth, et al. (2010) 5-Year prognostic value of no-reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 55(21): 2383-2389.

- Verma S, Fedak PWM (2005) The optimal dose of intracoronary nitroprusside in the treatment of the no-reflow phenomenon. International Journal of Cardiology, 102(3): 491-492.

- Gori T, Münzel T (2011) Biological effects of nitroglycerin and other nitrogen oxides relevant to the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation, 123(19): 2132-2144.

- O Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Donald E Casey Jr, Mina K Chung, et al. (2013) 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 127(4): e362-e425.

- Ito H, Maruyama A, Iwakura K, S Takiuchi, T Masuyama, et al. (1996) Clinical implications of the 'no reflow' phenomenon. A predictor of complications and left ventricular remodelling in reperfused anterior wall myocardial infarction. Circulation, 93(2): 223-228.

- Stone GW, Peterson MA, Lansky AJ, Dangas G, Mehran R, et al. (2002) Impact of normalized myocardial perfusion after successful angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 39(4): 591-597.

- Niccoli G, Burzotta F, Galiuto L, Crea F (2012) Myocardial no-reflow in humans. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 56(9): 752-758.

- Suryapranata H, Tan E, Ottervanger JP, de Boer MJ, Zijlstra F (2005) Primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Current Problems in Cardiology, 30(5): 267-318.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...