Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4544

Case Report(ISSN: 2637-4544)

Placenta Accreta: Case Report From Ultrasound diagnosis to Treatment Volume 1 - Issue 5

E Pilloni*, E Viora, A Sciarrone, P Cortese, C Monzeglio, M Biasio and G Botta e G A Gregori

- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sant’ Anna Hospital, Turin, Italy

Received: April 23, 2018; Published: April 30, 2018

Corresponding author: E Pilloni, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sant’ Anna Hospital, Turin, Italy

DOI: 10.32474/IGWHC.2018.01.000124

Introduction

Placental attachment disorder encompasses a spectrum of conditions characterized by abnormaladherence of placenta to the implantation site, with threevariantsclassifiedaccording to theirdegree of trophoblastic invasion through the myometrium and the uterine serosa.

Placenta accreta is the most common variant and is defined as trophoblastic attachment to the myometrium without intervening decidua [1]; placenta percretais the most serious variant because placenta invades the uterine serosa. All varieties are associated with a significant increase in maternal morbidity and mortality, mainly due to bloodloss, local organ damage, urgent hysterectomy (33-50%) and postoperative complications [2,3]. Placenta previa and previous uterine surgery are the major risk factors for invasive placentation [4,5]. Placenta previa is defined as a placenta that either lies in closeproximity to the internal cervicalos or partially or completelycoversit [1]. Placenta previa and accreta and theircomplications are increasing due to a higher number of Cesarean sections being performed and advanced maternal age [1-6]. Although placenta previa isper se a risk factor, the most common is a uterine scar. The risk increases from 0.3% after one prior Cesarean section to 0.6, 2.1, 2.3 and 6.7% after two, three, four and more than four Cesarean sections, respectively [7]. The principal maternal complication is massive hemorrhage, that then leads to disseminatedintravascular coagulation, multi organ failure ad even death; Wright et al estimated a median bloodloss in cohorts of accretas from 2.000 to 7800 ml [8]. Peripartum hysterectomy rates is 30-55% [9] and maternal death has been reported in 5-7% of cases [10]. As there are reports in the literature that maternal complications, such as peripartum blood loss andneed for blood transfusion, are reducedwhenthe delivery isarranged in a centre of execellence, an accurate antenatal diagnosis of invasive placentation is important [9,11,12]. Further more prenatal diagnosis allows for optimal management, which typically includes planned cesarean hysterectomu before the onset of labor or bleedig [10]. In referred center a case of placenta accreta is managed by a multidisciplinary team that includes specialists in maternal-fetal medicine, obstetric ultrasound, gynecologic surgery and oncology, urologic surgery trasfusion medicine, intensive care, neonatology and anesthesioloy.

It’simportant to refercases of placenta accreta to a centre of excellencealso for the diagnosis: in factultrasoundsensitivity in the second-thirdtrimester of pregnancy for the identification of placenta accreta with expertsoperators and in case of anterior placenta previaisreported to be 80-90% [10,3,13]. Ultrasound criteria suggesting placenta accreta spectrum are: lossor irregularity of the hypoechoic area between theuterus and placenta (the ‘retroplacentalclear zone’),thinning or interruption of the uterineserosa-bladder wall interface,myometrial thickness<1mm,turbulent placental lacunae with high velocity flow (>15 cm/s), increased and irregular subplacental vascularity, vessels between placenta and bladder [13-15]. The optimal timing of delivery for placenta accretas and its variants remains controversials: the risks of prematurity must be balanced against the risk of emergency delivery in the setting of labor or bleeding. Time of delivery should be individualized, butitmay be reasonable to planbetween 34 and 35 weeks of gestation, until 36 weeks in stable and asyntomatic patients (withoutbleedingepisodes and contractions) [10,12,16]. Hospitalization is recommended for patients with bleeding or for patientsthat live far from an appropriate medical center. The delivery should be performed in an operating room with support services needed to manage potential complications. Institutionally established massive transfusion protocols should be followed and packed red bloodcells and plasma should be available in the operative room [10,16]. In case of placenta accreta the abdominal incision should allow for easy performance of a difficulth is terectomy, tipically a verticalin cision, and the optimal surgical approach is fundal histerotomy to avoid touching placenta. The use of pelvic devascularization with balloon catheters in internal iliac arteries or surgical hypogastric artery ligation is controversal because of the important collateral circulation to the uterus with placental attachment disorders [10,12,16,17].

Case Report

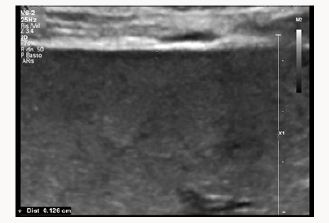

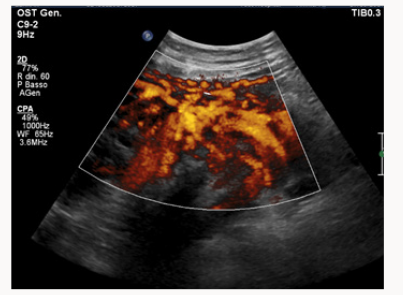

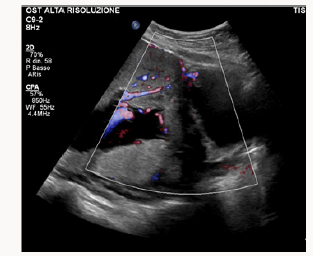

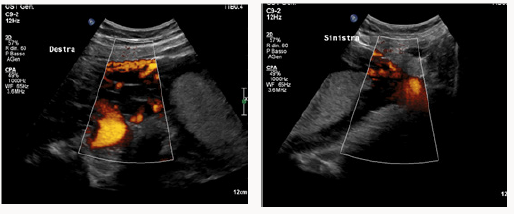

A 37yearsold, Egyptian woman with 3previous cesarean section was reffered to our centre for important anemia (hemoglobin 6,5 g7dL)withouth bleed in gat 24 weeks of gestations. Previous ultrasound exam were done in Egypt. At ultrasound control a placenta previa major (anterior placenta that cover and passes internal uterine orifice)was diagnosed, with these signs of accretism: placental lacunae (Figure 1), in existent myometrial thickness (Figure 2) from istmic zone to the cervix, notvisualizion of retro placentar clear zone (Figures 3 & 4), discontinuity of the line between uterus and bladder (Figure 4) increased and irregular placental vascularization (Figure 5), expecially between uterus and bladder (Figure 6), the presence of large vessels in right parametrium (Figures 7 & 8). Blood trasfusions of 4 bloodunits and cortichosteroids prophylaxis for neonatal respiratory distress syndrome were performed; during the hospitalization there weren’t contractions and vaginal bloodloss, so the woman went home from 28 to 31 weeks. Thenat 31 weeks there was a small bleeding and so the patient was hospitalized again.

Figure 7 and 8: Difference between vascularisation of right (more irregular vessels) and left parametrium.

The delivery wasplannedat 34 weeks of gestationsafter a rescue dose of cortico steroids because the presence of contractions and the bleeding episode. The delivery was planned with multidisciplinary expert team with 2 anesthesiologist, three experts in gynecological oncology surgery, with immediately available trasfusion, blood recovery equipment and neonatology team in surgical room.

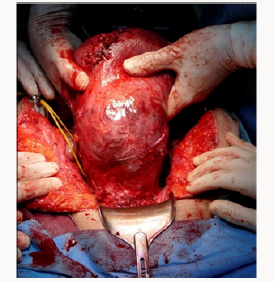

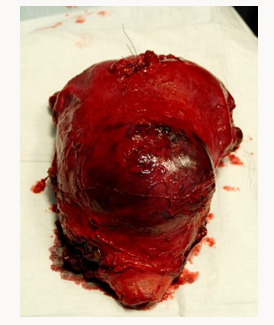

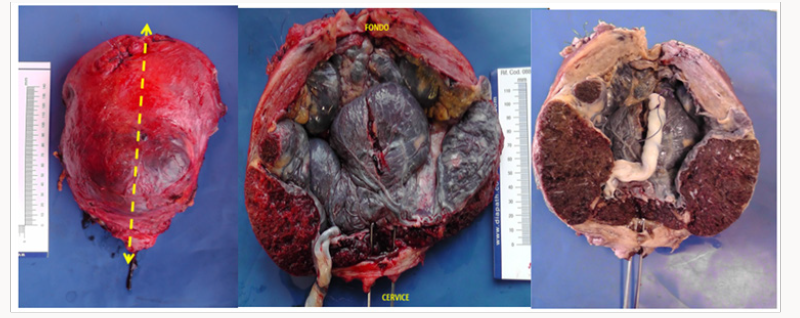

The abdomina lincision was vertical and the fetus was delivered bay incision on the fundus to avoid compromising placenta percreta. Placenta appeared to reached seorsa without myometryum in the anterior part of the uterus (Figure 9). Then the cord was bounded, the placenta was left in situ and the incision was closed. Then surgeries isolated and proceeded with left hypogastric artery ligations. In the right side therewas an important vascularization (described during the ultrasound exams) with large vessels and so they didn’t proceed with pelvicd evascularization. Then they made total hysterectomy, before identification of ureters (Figure 10).Total blood loss was of 1500 ml, of which 300 ml were infused. Pathologial examination confirme the presence of placenta accreta and increta, myometrium of only 1 mm in the istmicportion (Figures 11-13). The woman was trasferred in intensive therapy for 3days. The baby born with Apgar score of 7/8, weight 2550 g, transferred in intensive neonatal therapy. Mother and baby went home after 9 days.

References

- Clark SL, Koonings PP, Phelan JP (1985) Placenta previa/accreta and prior cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol 66(1): 89-92.

- D’antonio F, Iacovella C, Bhide A (2013) Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: systematic review and metaanalysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecols 42(5): 509-517.

- Comstock CH, Bronsteen RA (2014) The antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. BJOG 121(2): 171-182.

- Fitzpatrick KE, Sellers S, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P, et al. (2012) Incidence and riskfactors for placenta accreta/increta/percreta in the UK: a national case-control study. PLoSOne 7(12): e52893.

- Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM (1997) Clinical risk factors for placenta previa-placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 177(1): 210-214.

- Usta IM, Hobeika EM, Musa AA, Gabriel GE, Nassar AH (2005) Placenta previa-accreta: risk factors and complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193(3 Pt 2): 1045-1049.

- Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, et al. (2006) Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol 107(6): 1226-1232.

- Wright JD, Pri Paz S, Herzog TJ, Shah M, Bonanno C, et al. (2011) Predictors of massive bloodloss in women with placenta accreta. Am J ObstetGynecol 205(1): e1-e6.

- Comstock CH (2011) The antenatal diagnosis of placental attachment disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 23(2): 117-122.

- Silver RM (2015) Abnormal placentation: Placenta Previa, Vasa Previa, and Placenta Accreta. Obstetrics Gynecology 126(3): 654-668.

- Tikkanen M, Paavonen J, Loukovaara M, Stefanovic V (2011) Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta leads to reduced bloodloss. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 90(10): 1140-1146.

- (2011) Placenta Praevia, Placenta Praevia Accreta and VasaPraevia: Diagnosis and Management (Green-top Guideline No. 27). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG).

- E Pilloni, MG Alemanno, P Gaglioti, A Sciarrone, A Garofalo, et al. (2016) Accuracy of ultrasound in antenatal diagnosis of placental attachment disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 47(3): 302-307.

- Shih JC, Palacios Jaraquemada JM, Su YN, Shyu MK, Lin CH, et al. (2009) Role of three-dimensional power Doppler in the antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta: comparison with gray-scale and color Doppler techniques. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 33(2): 193-203.

- Cali G, Giambanco L, Puccio G, Forlani F (2013) Morbidly adherent placenta: evaluation of ultrasound diagnostic criteria and differentiation of placenta accreta from percreta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 41(4): 406-412.

- (2012) Committee opinion, Placenta accreta. ACOG pp. 529.

- Allahdin S, Voigt S, Htwe TT (2011) Management of placenta praevia and accreta. J Obstet Gynaecol 31(1): 1-6.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...