Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4544

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4544)

Factors Affecting Birth Weight of Newborns Among Neonates Born at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia Volume 4 - Issue 3

Wassachew Ashebir1*, Birhanu Miried2

- 1Department of Public Health, College Of Health Science, Debre Markos University, Ethiopia

- 2Debre Markos Referral Hospital, East Gojam Zone, Ethiopia

Received: December 18, 2020Published: March 24, 2021

Corresponding author: Wassachew Ashebir, Debre Markos University, College Of Health Science, Department Of Public Health.

DOI: 10.32474/IGWHC.2021.04.000192

Abstract

Background: The weight of an infant at birth matters since it is a reliable reflection of intrauterine growth. Low birth weight remains to be a leading cause of neonatal death and is a major contributor to infant and under-five mortality. Reducing infant mortality is a global priority which is particularly relevant in developing countries including Ethiopia. To do this, preventing the risk of low birth weight and improving birth weight remains essential. However, measuring weight at birth and documenting the toll of low birth weight with its various factors in Ethiopia is not well. studied. Hence, the main aim of this study was to determine prevalence and identify factors affecting birth weight of newborns born at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods: An institutional based cross-sectional study was employed among mothers who gave a live birth neonate at Debre Markos Referral Hospital from January 01 to February 30. A total of 227 mother-newborn pairs were selected using systematic random sampling techniques. An interviewer administered and structured questionnaire was used to collect data. The data was entered, cleaned and edited using EPI data and exported to SPSS version for analysis. Both bivariate and multivariate logistic regression were fitted and odds ratio and 95% CI were computed. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistical significant.

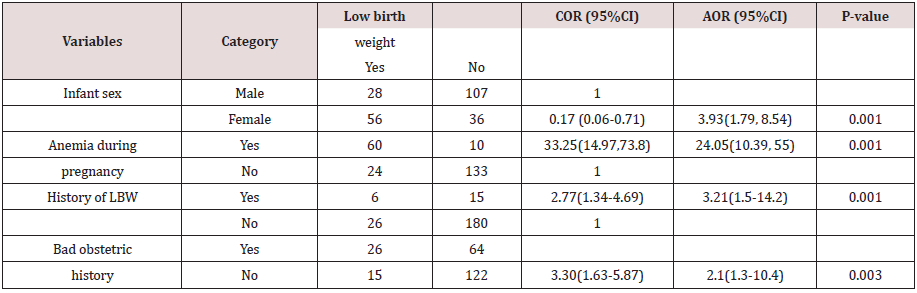

Result: The overall prevalence of low birth weight was 37 %. In this study, sex of the newborn (AOR = 3.93, 95% CI: (1.79, 8.54)), previous history of low birth weight (AOR = 3.21, 95% CI:(1.5-14.2)), anemia during current pregnancy (AOR=24.05; 95% (10.39, 55) and having bad obstetric history (AOR=2.1; 95% (1.3-10.4) were the significant predictors of low birth weight.

Conclusion: There was a high prevalence of low birth weight in the study area. Hence, health care providers should give especial emphasis on focused antenatal care to ensure risk of low birth weight is detected early and treated appropriately. They should be followed up to ensure normal progression of pregnancy.

Keywords: Birth weight; Newborn; Low birth weight; Giving birth

Abbreviations: ANC; Antenatal care; AOR; Adjusted odds ratio; CI; Confidence interval; COR; Crude odds ratio; LBW; Low birth weight; MUAC; Mid-upper arm circumference; SSA; Sub Saharan Africa; WHO; World health organization

Plain English Summary

The aim of this study was to assess prevalence and identify factors affecting birth weight of newborns among neonates born at Debre Markos Referral Hospital. Understanding key drivers of a newborn’s low birth weight is one of the steps towards identifying amenable maternal and social factors to target and improve pregnancy outcomes. Two hundred twenty-seven neonates delivered at Debre Markos Referral Hospital; Northwest Ethiopia were participated in this study. Interviewer–administered and pretested questionnaire was used to measure the main variables of socio- demographic characteristics of mothers and their neonates, women’s obstetric and behavioral related characteristics and their neonatal characteristics and outcomes. The results suggest that over one third (37%) of neonates were found to have a weight less than 2500g, that is being low birth weight babies. Low birth weight of neonates was significantly associated with being female, newborn sex, having previous history of low birth weight, having anemia during current pregnancy and having bad obstetric history. Therefore, it is essential to address these important factors with more emphasis on providing focused quality antenatal care during pregnancy to ensure risk of low birth weight is detected early and treated appropriately.

Background

The weight of an infant at birth matters since it is a reliable reflection of intrauterine growth and also a critical predictor of the child’s physical, emotional, and psychological growth later in life [1,2]. Being an important milestone, birth weight of an infant is dependent on amount of growth during pregnancy and the gestational age, and these factors are also related to the genetic makeup of the infant and the mother, her lifestyle and her status of health [3]. In line with this idea and as per WHO definition, babies with a birth weight of less than 2500g regardless of their gestational age are considered as low birth weight (LBW) newborn [4]. Worldwide, low birth weight continues to be a major public health challenge and resulted with a range of both short- and long-term consequences. It remains to be a leading cause of neonatal death, and a highly contributor to infant and under-five mortality. In most developing countries, it was approximated that every ten seconds an infant dies from a disease or infection that can be attributed to LBW. In 2017 alone, 2.5 millions of neonates died, due to low birth weight, prematurity and other preventable causes of neonatal death [5]. Evidences suggested that children born with LBW are prone to mortality and have shown increased risk of cognitive and poor school performance as their normal birth weight peers [6]. Some other recent studies also showed that LBW increased the risk for non-communicable diseases such as respiratory illness, coronary heart disease, and diabetes, which all have long-term deleterious consequences in adulthood [7]. Overall, it is estimated that 15% to 20% of all births worldwide are LBW, representing more than 20 million births a year. Of these, the great share (96.5%) of the LBW is own by developing countries. Based on WHO further notice, the prevalence of LBW varies across regions and ranges between 6% and 28%, with East Asia recording the highest proportion [8]. It is worth noting that these rates are high, in spite of the fact that the data on LBW remain limited or unreliable, as many deliveries occur in homes or small health clinics and are not reported in official figures, which may result in an underestimation of9 the prevalence of LBW. There is considerable variation in the prevalence of low birth weight across regions and within countries; however, the great majority of low birth weight births occur in low- and middleincome countries and especially in the most vulnerable populations [9,10]. The level of low birth weight in developing countries (16.5 percent) is more than double the level in developed regions (7 per cent). Half of all low birth weight babies are born in South-central Asia, where more than a quarter (27 percent) of all infants weighs less than 2,500 g at birth. A low birth weight level in sub-Saharan Africa is around 15 percent. More commonly, in developing than developed countries, a birth weight below 2,500 g contributes to several poor health outcomes [11]. Currently, a high percentage of infants are not weighed at birth, especially in low-income countries, presenting a significant policy challenge. There is also substantial intra-country variation. In SSA, 13% of infants are with low birth weight and 54% of infants not weighed at birth. Similarly, 11% of infants in Eastern and southern Africa are low birth weight with 46% of infants not weighed at birth [12]. WHO country cooperation strategy 2008 – 2011 showed that the prevalence of low birth weight in Ethiopia, estimated that 14%, it is one of the highest in the world [13]. According to the 2005/06 annual activity report of the Addis Ababa City Administration, Health Bureau, the rate of LBW among all deliveries attended from health institutions reporting to the city health bureau is 11%. According to studies, in Ethiopia, there is a difference in the prevalence of low birth weight between geographical areas with a range from 8.4% to 28.3% [14-16]. As one of the undesirable birth outcomes, LBW found to have immediate determinants such as health and nutritional factors. These factors are to a great extent influenced by socio-economic, cultural and demographic factors. There are multiple causes of low birth weight, including early induction of labor or caesarean birth (for medical or non-medical reasons), multiple pregnancies, infections and chronic conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure [17]. Previous many studies indicated that various socio-demographic, obstetrics and fetal factors are predictors of low birth weight [18-21]. A study conducted in the Northwest Ethiopia revealed that being a preterm, absence of antenatal care, and malarial attack during pregnancy, anemia during pregnancy and lack of iron supplementation were the independent predisposing risk of low birth weight [22]. Underlying factors affecting birth weight of a newborn revolve around social, environmental, individual, and gynecological aspects [23]. As geography and socioeconomic circumstances differ across countries and local contexts, this can lead to a benchmark in areas of the research to focus on. Understanding key drivers of a newborn’s low birth weight, is one of the steps towards identifying amenable maternal and social factors to target and improve pregnancy outcomes. The likely possible positive social change implication for this study is that, once amenable maternal factors have been identified, health programs may be designed to target and modify those factors. In turn, such interventions may result in, among others, reduced neonatal morbidity, mortality and the upcoming suffering to the family as a whole. Reducing infant mortality is a global priority which is particularly relevant in developing countries including Ethiopia. One of the key strategies to reduce infant mortality rate and improving child health is preventing the risk of low birth weight and improving birth weight [24]. To do this, preventing the risk of low birth weight and improving birth weight remains essential. However, measuring weight at birth and documenting the toll of low birth weight with its various factors among health institutions in Ethiopia context is not well studied. Hence, the main aim of this study was to determine prevalence and identify factors affecting birth weight of newborns among neonates born at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting, design and period.

An institutional based cross-sectional study was employed among women who delivered at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia from January 1 to February 30 during the study period. The Hospital is located on the southern part of Debre markos town. The town is found in Amhara Regional State 300 Km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia and 265 Km from Bahir Dar. It has an altitude of 2450- 2520 m above sea level and average temperature ranging from 15-22oc.

Study population, sample size and sampling

The study populations were mothers who gave a live birth neonate at Debre Markos Referral Hospital during the study period. A sample size of 227 study participants was calculated using a single population proportion formula with a 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, and prevalence of low birth weight in Gondar as 18% [25, -28]. and by considering a non-response rate of 10%. Systematic random sampling technique was used to obtain the study sample and selecting the first women by lottery method.

Data collection methods and procedures

Data was collected using structured questionnaire and face to face interviewing was used to collect relevant information to achieve the stated research objective. Their anthropometric measurements i.e.weight, height and MUAC were also taken. Birth weights of the infants were taken within 48 hours after birth to avoid effect on birth weight by postnatal weight loss. Two data collectors who were qualified health workers was participate in the data collection process. Training and thorough information was given to the data collectors on how to conduct the data collection. Anthropometric measurements (weight) was done according to WHO standard manual [11]. Data on morbidity was extracted from the mother and child health booklet and maternity register, as well as from interviews with the mothers. Mothers were also asked about health seeking behaviors such as the number of Antenatal Care Clinic (ANC) visits they had during pregnancy and use of mosquito nets. Infant weight at birth was taken immediately after delivery using pediatric weighing scale with a precision of 0 01 kg.

Measurements

The outcome variable of interest in this study, birth weight was measured based on anthropometric assessment. Accordingly, the weight of all live birth deliveries in that hospital was measured within 24 hours of birth. As a result, birth weight was divided into two categories namely low birth weight (less than 2500g) and normal birth weight (2500g and above). The prevalence of LBW was then calculated as dividing the total birth weights <2500g to the total live births and multiplying it with 100. Finally, the variable LBW was categorized as low birth weight and normal birth weight for analysis. Other independent variables like previous history of lbw, bad obstetric history etc was by asking the women and categorizing the response as YES or NO.

Statistical analysis

Data was entered in EPI data computer programs to minimize data entry error. The data entered was exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 for analysis. Then recoded, categorized and sorted to facilitate its analysis. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the percentages and number distributions of the respondents by socio-demographic characteristics and other relevant variables in the study. All descriptive statistics was computed. Personal Computer Frequencies and cross tabulations was used to summarize descriptive statistics of the data and tables and graphs were used for data presentation. Bivariate analysis was used primarily to check which variables have association with the dependent variable individually. Then, multivariate logistic regression was used to identify the independent predictors of low birth weight at 95% CI and significance level of <0.05 at cut off point.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical review board of DMU. Communication with the different Hospital Administrator and health professional was made through formal letter obtained from DMU. After the purpose and objective of the study was informed, verbal consent was obtained from each study participants. Participants were also informed that participation were on voluntary basis and they can withdraw from the study at any time if they are not comfortable about the questionnaire. In order to keep confidentiality of any information provided by study participant, the data collection procedure were anonymous.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

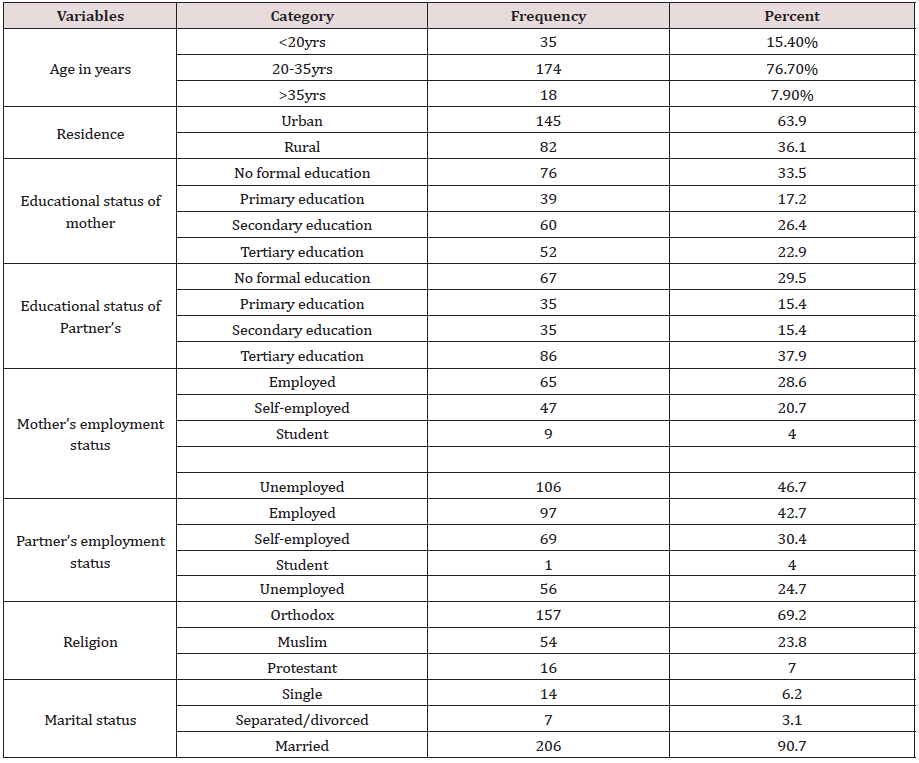

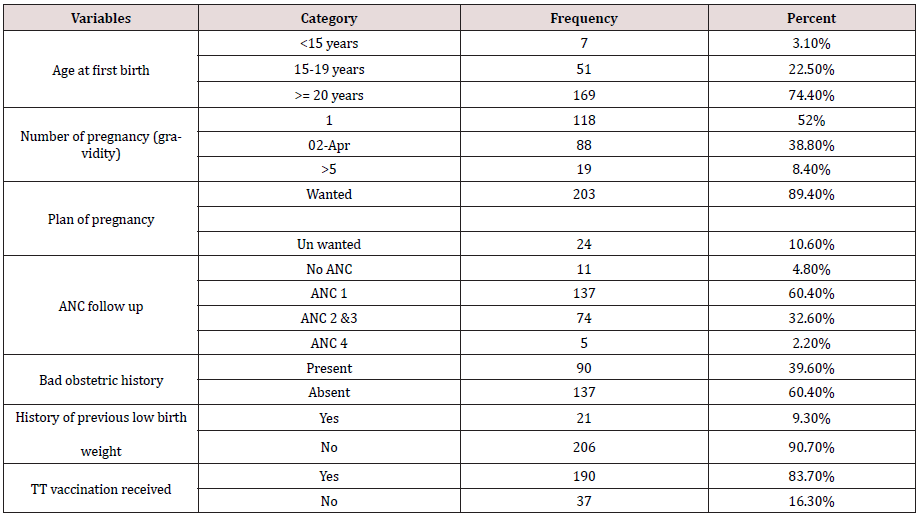

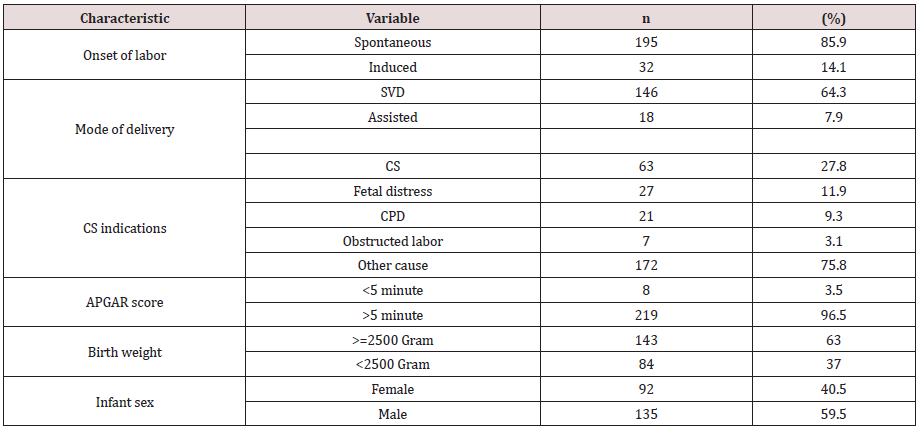

A total of 227 neonate/mother pairs were participated in this study making a response rate 100%. The mean age of the respondents/mothers were 25.99 ±5.7 years. Over 76% of the live births were born to mothers whose age was 20–35 years at childbirth. One hundred forty five (63.9%) of the sampled women were urban residents. Slightly greater than one-third of mothers (33.5%) had no formal education. Regarding their partners educational status, 86 (37.9%) of them had completed tertiary education. With Regards to mother’s employment, 46.7% of them were unemployed while 42.7% of their partners were employed. In terms of religion, most of the participants, 69.2% are Orthodox Christians and above 90% of them were married (Table 1). The age at first birth for the vast majority of respondents (74.4%) were > 20 years. Maternal gravidity ranges from 1 to five with primigravida accounts for the larger proportion that is 118 (52%). Among all women, over 89% pregnancies were planned. Regarding antenatal care (ANC), 137 (60.4%) respondents had ANC followup at least once during current pregnancy, and 190 (83.7%) of them had received TT immunization. Among all respondents, 90 (40%) of them reported bad obstetric history while 21(9.3%) of the women had a low birth weight in their previous pregnancy (Table 2). In relation to medical illnesses during women’s current pregnancy, seventy (30.8%) of mothers had anemia, malaria by 78 (34.4%), pregnancy-induced hypertension by 33 (14.5%), HIV by 14 (6.2%), tuberculosis by 45 (19.8%) and vaginal bleeding by19 (8.4%). Alcohol and cigarette smoking were practiced by 34 (15%) and 2 (0.9%) mothers, respectively. Iron and folic acid was taken by 215 (55.1%) mothers during the current pregnancy. One hundred fifty one (66.5%) of respondents get nutritional counselling and majority (44.5%) of them had three times frequency of meal per day. With regard to the mode of delivery, spontaneous vaginal delivery accounted for 146 (64.3%) mode of deliveries whereas assisted and cesarean section were figured by 18 (7.9%) and 63 (23.8%) mothers, respectively. The onset of labor for the majority (85.9%) were started spontaneously. One hundred thirty five (59.5%) neonates were male in sex (Table 3). Table 3: Labor and delivery characteristics of mothers delivered at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, East Gojam Zone, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018 (n=227).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of women delivered at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, East Gojam Zone, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018 (n=227).

Table 2: Obstetric and Neonatal Related Factors of women delivered at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, East Gojam Zone, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018 (n=227).

Table 3: Labor and delivery characteristics of mothers delivered at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, East Gojam Zone, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018 (n=227).

Magnitude of Low Birth Weight

In this study, the magnitude of low birth weight was 37 %. Out of 227 newborns delivered in the hospital during the study period, 84 were low birth weight.

Factors Associated with Low Birth Weight

In binary logistic regression analyses, variables including previous history of low birth weight, women having no nutritional counselling, women having no iron and folic acid intake during current pregnancy, bad obstetric history, women who had premature rupture of membrane, and infant sex had showed significant association with low birth weight. Then, multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was done by taking variables showing significant association on bivariate analysis at a p-value of ≤0.2 to adjust the possible confounding variables. In this way, infant’s sex, anemia during pregnancy, previous history of LBW and bad obstetric history were predictors of low birth weight at AOR (95%CI). Women who gave birth of a female newborn were 3.9 times more likely to delivered low birth weight baby than their counterparts (AOR = 3.93, 95% CI: (1.79, 8.54)). Women who had previous history of low birth weight had 3.2 times higher odds ratio of delivered low birth weight baby than their counterparts (AOR = 3.21, 95% CI: (1.5-14.2)). Mothers who had anemia during pregnancy were 24 times higher risk of getting low birth weight newborn compared to those no anemia (AOR=24.05 ;95% (10.39, 55). The odds of low birth weight among mothers with bad obstetric history were two times more likely compared with those who had not (AOR=2.1 ;95% (1.3-10.4). (Table 4).

Table 4: Multivariable analysis results for factors affecting birth weight of newborns among mothers delivered at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, East Gojam Zone, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018 (n=227).

Discussion

This study was aimed at determining the magnitude of low birth weight and factors affecting birth weight of newborns among mothers who delivered at Debre Markos Referral Hospital. Based on the finding of this study, 37% of neonates were born with low birth weight. This finding is higher than the study done in India 11% [29]. and study conducted in Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia (18%) [30-35]. And in Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia (22.5%) [36]. The possible difference with Indian study might be mothers in India have better disease screening and prevention and also there might be access to better nutrient before and after conception. But, the likely difference with studies done in Gondar might be due to presence of teaching hospital in Gondar that make women’s to have better health service. This study also showed that infant’s sex, anemia during pregnancy, previous history of LBW and bad obstetric history were found to be the independent predictors of low birth weight. This study showed that sex of the new born has significant association with birth weight of the newborns. This finding is supported with a study in Gondar where being female has two fold risks for low birth weight [37,39]. The results were similar to findings in other settings [40, 41]. One study was carried out in Brazil demonstrated this issue because the mean weight of a female fetus is lower than that of a male one [37]. The possible justification might be male hormones promote masculinity making males generally heavier than females throughout the lifecycle. Anemia during pregnancy was independently and significantly associated with LBW. This is supported by previous works [39]. The higher risks of giving birth to LBW neonates by mothers who are anemic reflects the positive role a diet rich in iron plays during the period covered by the pregnancy. Those women having previous history of LBW had higher odds to have delivery of LBW neonates than women who did not have previous history. This result is similar to the study conducted in Nigeria [35]. This study showed significant association between bad obstetric history and occurrence of low birth weight. The possible explanation is that mother who had bad obstetric history have no their obstetric problem detected and treated or referred earlier.

Conclusion

The prevalence of low birth weight in Debre Markos Referral Hospital is higher than national and local estimates: and also, high enough to raise concern as a public health problem. Infant’s sex, anemia during pregnancy, previous history of LBW and bad obstetric history were found to be the independent predictors of low birth weight.

Recommendations

With regard to the high low birth weight prevalence, there is need for health care providers in Debre Markos Referral Hospital to put more emphasis on focused antenatal care to ensure risk of low birth weight is detected early and treated appropriately. They should be followed up to ensure normal progression of pregnancy. Since lowbirth- weight newborns are at risk of asphyxia at birth, it is similarly important for the hospital to ensure availability of equipment and skilled staff for newborn resuscitation. A longitudinal study should be done from the period prior to conception through pregnancy to after deliver.’ to allow for a close follow-up of the subjects and evaluate the factors contributing to low birth weight in a causeeffect model for development of specific interventions.

References

- World Health Organization (2007) World Health Statistics 1: 1-97.

- Fraser D, Cooper MA (2004) Myles tex book for midwives (14th edn). Churchill living stone.

- World Health Organization (2006) Promoting optimal fetal development report of a technical consultation.

- World Health Organization. Global targets 2025. To improve maternal, infant and young child nutrition (www.who.int/nutrition/topics/nutrition_ globaltargets2025/en/, accessed 17 October 2014).

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Driscoll AK, Mathew TJ, (2017) Births: final data for 2015 National Vital Statistics Reports 66(1).

- Mulder H, Pitchford NJ, Marlow N (2011) Inattentive behavior is associated with poor working memory and slow processing speed in very pre-term children in 113 middle childhood. British Journal of Education Psychology 81(1): 147-160

- Negrato CA, Gomes MB, (2013) Low birth weight: Causes and consequences. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child.

- In: Sixty-fifth World Health Assembly Geneva, 21–26 May 2012. Resolutions and decisions,annexes.Geneva:World Health Organization;2012:12–13

- Kim D, Saada A (2013) The social determinants of infant mortality and birth outcomes in western developed nations: a cross-country systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10(6): 2296-335.

- Muglia LJ, Katz M (2010) The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N Engl J Med 362(6): 529–35.

- BM Zeleke, M Zelalem, N Mohammed (2012) Incidence and correlates of low birth weight at a referral hospital in Northwest Ethiopia Pan African Medical Journal 12(1).

- World Health Organization. (2014). Global nutrition targets 2025: Policy brief series. WHO/NMH/NHD/14.2). Retrievedfrom

- Undernourishment in the womb can lead to diminished potential and predisposes infants to early United Nations Children’Fund; 2014

- Nutrition and food safety, WHO country cooperation strategy 2008-2011, Ethiopia, page12

- Teklehaimanot N, HailuT, Assefa H (2014) Prevalence and factors associated with low birth weight in Axum and lay may chew districts, North Ethiopia: a comparative cross sectional study. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences 3(6):560-566.

- Temat T (2006) Prevalence and determinants of low birth weight in Jimma zone southwest Ethiopia. East African Medical Journal 83(7): 366-71.

- Assefa N, BerhaneY, Worku A (2012) “Wealth status, mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) and Ante Natal Care (ANC) are determinants for low birth weight in Kersa, Ethiopia 7(6).

- Larroque B, Bertrais S, Czernichow P, Leger J (2001) School difficulties in 20-yearolds who were born small for gestational age at term in a regional cohort study. Pediatrics 2001;108(1):111-15.

- March of Dimes, The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health, Save the Children, WHO. Born too soon: the global action report on preterm birth. Geneva: World Health Organization:2012.

- Risnes KR, Vatten LJ, Baker JL, Jameson K, Sovio U, et al. (2011) Birth weight and mortality in adulthood a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 40(3): 647-61.

- Kader M, Perera NP (2014) Socio-economic and nutritional determinants of low birth weight in India. North American Journal of Medical Sciences 6(7): 302--308.

- Kaur S, Upadhyay AK, Srivastava DK, Srivastava R, Pandey ON (2014) Maternal correlates of birth weight of newborn A hospital-based study. Indian Journal of Community Health, 26(2): 187-191.

- W Kumlachew, N Tezera, A Endalamaw (2018) Below normal birth weight in the Northwest part of Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes 11(1): 611.

- Madden D (2014) The relationship between low birth weight and socioeconomic status in Ireland. Journal of Biosocial Science 46(2): 248-265.

- World Health Organization. (2017) WHO recommendations on maternal health: guidelines approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee. Geneva World Health Organization.

- Gbenga A Kayode, Mary Amoakoh-Coleman , Irene AkuaAgyepong , Evelyn Ansah, Diederick E. Grobbee et al. (2014) Contextual Risk Factors for Low Birth Weight A Multilevel Analysis 9(10).

- Zeleke B, Zelalem M, Mohammed N (2012) Incidence and correlates of low birth weight at a referral hospital in Northwest Ethiopia. Pan African Medical Journal 12: 4.

- Siza JE (2008) Risk factors associated with low birth weight of neonates among pregnant women attending a referral hospital in northern Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Health Research 10(1): 1-8.

- Walter EC, Ehlenbach WJ, Hotchkin DL, Chien JW, Koepsell TD (2009) Low Birth Weight and Respiratory Disease in Adulthood: American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 180(2): 176-180.

- Badshah S, Mason L, McKelvie K, Payne R, Lisboa P (2008) Risk factors for low birth weight in the public-hospitals at Peshawar, NWFP-Pakistan. BMC Public Health 8: 197.

- Roudbari M, Yaghmaei M, Soheili M (2007) Prevalence and risk factors of low-birth-weight infants in Zahedan, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediter Health 13(4): 838–845.

- Louangpradith Viengsakhone, Yoshitoku Yoshida, harun-or-rashi and Determinant of low birth weight in Vientiane Laos, Sakamoto1 nagoya J.Med. Scl, 2010, 72.51-58.

- Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, 2016.

- Donnelley JF, Flowers CE, Creadik RN, Greenberg BG, Surles KB (1994) Maternal fetal and environmental factors in prematurity. Amer J Obstet Gynaec 88(7): 918-931.

- Mahari Yihdego, Mizan-Tepi University Dr. Alemayohu Mekonnen, AAU, Assessment of maternal risk factors associated with full-term low birth weight neonates in public health facilities of addis-ababa, Ethiopia: a case-control study.

- Swende TZ (2011) Term birth weight and sex ratio of offspring of a Nigerian obstetric population International. Journal Biological and Medical Research 2(2): 531-532.

- Gebremariam A (2005) Factors predisposing to low birth weight in Jimma hospital south western Ethiopia. East African Medical Journal November 82(11): 554-558.

- Barbieri MA, Silva AA, Bettiol H, Gomes UA (2000) Risk factors for the increasing trend in low birth weight among live births born by vaginal delivery Brazil. Rev Saúde Pública 34(6): 596-602.

- Kahsay Z, Tadese A, Nigusie B , Low Birth Weight & Associated Factors Among Newborns in Gondar Town, North West Ethiopia: Indo Global Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2014; 4(2): 74-80.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...