Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4544

Short CommunicationOpen Access

Changes in Skeletal System during Pregnancy Volume 2 - Issue 1

Mohamed Nabih EL Gharib1* and Amro D Aglan2

- 1Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Egypt

- 2Medical Student, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Egypt

Received: May 07, 2018; Published: May 14, 2018

Corresponding author: Mohamed Nabih EL-Gharib, Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Egypt

DOI: 10.32474/IGWHC.2018.02.000127

Introduction

Pain localized at the pelvic girdle during and after pregnancy has been keyed out and registered as an entity since the 4th century BC by Hippocrates. Contemporary medical research since the early 20th century has attempted to clarify the spectrum of the different pathologies that this clinical syndrome represents [1]. Up till now, the pregnancy causes changes in spinal curvature and posture remains open for further studies. One of the most frequent complications of pregnancy is low back pain, with 50±70% prevalence [2]. Its incidence is higher in the third trimester of pregnancy, when the most important biomechanical and morphological changes take place. From the second trimester, abdominal morphology is altered by the increased size of the uterus and the weightiness of the fetus, with a 30% gain in abdominal mass [3]. Despite the frequent occurrence of the problem, no explicit criteria for diagnosis and therapy guidelines are available in the literature. The increased size of the abdomen has been linked to a decreased static stability and adaptive changes in spinal curvatures, which would compensate the anterior displacement of the center of gravity, to ensure postural balance [4].

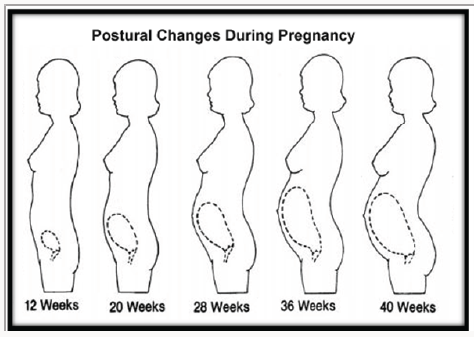

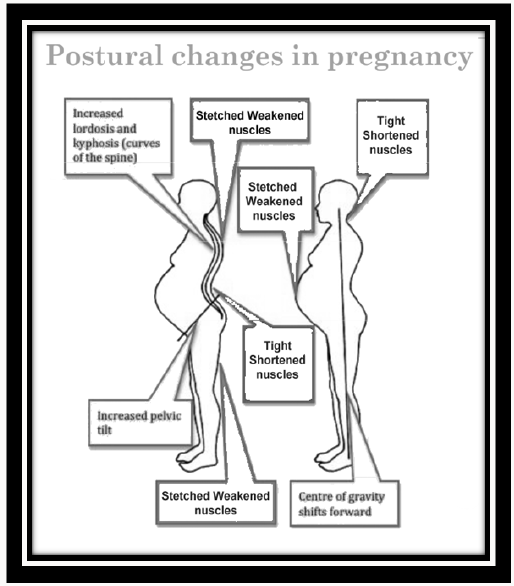

Postural alterations most frequently mentioned in the literature are increased lumbar curvature, pelvic ante version as illustrated in Figures 1 & 2; [5] increased thoracic curvature [6], increased cervical curvature, protraction of the shoulder girdle, hyper extended knees [7], and extension of the ankles [8] Walking is an essential daily activity and important in controlling adipose tissue weight gain associated with pregnancy [9,10]. The mechanics of walking, however may be affected as pregnancy, are characterized by maternal changes in shape and dimensions, particularly in the trunk. As pregnancy progresses, the lower trunk segment inertial characteristics show a significantly larger rate of increase than any other body segments. With rapid changes in mass, and moment of inertia, [11] trunk segment kinematics may be altered in daily activities such as walking. The possibility of altered kinematics is important as this may also affect the kinetics and hence musculoskeletal demands on the trunk segments [12]. Much of the focus on trunk mechanical adaptations in pregnancy has been on static postures [13]. These adaptive changes include:

I. Postural changes include forward head, rounded shoulders increased head, rounded shoulders, increased lumbar lordosis, hyper extended knees and pronated feet.

II. The core of gravity shifts forward, resulting in some balance disturbance.

III. Powerful changes are also distinctive and include shortened hip flexors, lower back musculature, and pectorals. Abdominal muscles, neck, and upper back muscle groups elongate. This may promote stretch weakness.

IV. Bones and joints: There is a tendency to decalcification of bones, sublaxation of joints due to softening of ligaments by relaxing hormone. It is more marked in sacroiliac joint and symphysis pubis, which allows stretching at the time of delivery of the baby.

V. It is due to the growth in size of the uterus and pressure along the abdominal wall. The patient walks with head and shoulders thrust back and chest protruding outward to cover. This affords the patient a “waddling” gait.

VI. Foti and associates reported an increased peak anterior pelvic tilt in late pregnancy when compared to one year postbirth with no differences in pelvic rotation in the transverse or coronal plane. No control group was used and differences may have been referable to natural human variability with retesting [14] (Figure 1 & 2).

Gait in pregnant women often comes out as a “waddle”–a forward gait that includes a lateral portion. Yet, research has shown that the forward gait alone remains unchanged during pregnancy. It has been set up that gait parameters such as gait kinematics, (velocity, step length, and cadence) remain unaltered during the third trimester of pregnancy and 1 year after delivery. These parameters indicate that there is no change in forward motion. There is, though, a significant gain in kinetic gait parameters, which may be employed to explain how gait motion remains relatively unchanged despite increases in body mass, width and changes in mass distribution near the waist during pregnancy. These kinetic gait parameters suggest an increased role of hip abductor, hip extensor, and ankle plantar flexor muscle groups. To pay for these gait deviations, pregnant women often makes adaptations that can result in musculoskeletal injuries. While the estimate of “waddling” cannot be distributed, these outcomes indicate that exercise and conditioning may help alleviate these injuries [14]. The foot is the most distal structure in the human body, it is in close contact with the ground, and is an integral component of the gait. The foot of a pregnant woman undergoes many changes as pregnancy advances. These modifications could be ascribed to the anatomical and physiological alterations that involve the musculoskeletal system. Understanding the structural changes of the foot during pregnancy and postpartum is important because any changes in the structure may alter the entire foot biomechanics, which can in turn vary the force propagation from the foot through the lower-limb joints of the spine. The foot of a pregnant woman undergoes morphological changes with the progress of pregnancy. It is significant to realize the morphological alterations of the foot during pregnancy and postpartum because any such change may alter the plantar pressure pattern and the entire foot biomechanics. The feet of pregnant women tend to get promoted as pregnancy advances, but do not reach baseline values even at 6 weeks postpartum. Pregnant women tend to bear more weight on the dominant foot with an increased static hind foot pressure as pregnancy progresses.

References

- Snelling FG (1870) Relaxation of pelvic symphysis during pregnancy and parturition. Am J Obstet 2(3): 561-596.

- Kovacs FM, Garcia E, Royuela A, Gonzalez L, Abraira V (2012) Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy. A multicenter study conducted in the spanish national health service. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 37(17): 1516-1533.

- Jensen RK, Doucet S, Treitz T (1996) Changes in segment mass and mass distribution during pregnancy. J Biomech 29(2): 251-256.

- Opala Berdzik A, Błaszczyk JW, Bacik B, Cieślińska Świder J, Świder D, et al. (2015) Static Postural Stability in Women during and after Pregnancy. A prospective Longitudinal Study. PloS One 10(6): e0124207.

- Franklin ME, Conner Kerr T (1998) An analysis of posture and back pain in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 28(3): 133-138.

- Bullock JE, Jull GA, Bullock MI (1987) The relationship of low back pain to postural changes during pregnancy. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy 33(1): 10-17.

- Gleeson PB, Pauls JA (1988) Obstetrical physical therapy. Review of the literature. Phys Ther 68 (11): 1699-1702.

- Fries EC, HF (1943) The influence of pregnancy on the location of the center of gravity, postural stability, and body alignment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 46(3): 374-380.

- Maturi MS, Afshary P, Abedi P (2011) Effect of physical activity intervention based on a pedometer on physical activity level and anthropometric measures after childbirth: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Child birth 11: 103.

- Gilleard WL (2013) Trunk motion and gait characteristics of pregnant women when walking: report of a longitudinal study with a control group. Pregnancy and Childbirth 13: 71.

- Gilleard W, Crosbie J, Smith R (2002) Static trunk posture in sitting and standing during pregnancy and early postbirth. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 83(12): 1739-1744.

- Foti T, Davids J, Bagley A (2000) A biomechanical analysis of gait during pregnancy. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 82(5): 625-632.

- Gijon Nogueron GA, Gavilan Diaz M, Valle Funes V, Jimenez Cebrian AM, Cervera Marin JA et al. (2013) Anthropometric foot changes during pregnancy: a pilot study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 103(4): 314-321.

- Segal NA, Boyer ER, Teran Yengle P, Glass NA, Hillstrom HJ, et al. (2013) Pregnancy leads to lasting changes in foot structure. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 92(3): 232-240.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...