Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1652

Case Report(ISSN: 2641-1652)

Mesenteric Venous Ischemia Secondary to Thrombophilia: Case Report Volume 1 - Issue 4

Amer N1*, Sallout I2, Hussein M3, Al Salman F2, Al Gamdi A2, Al Faleh M2 and Shahbahai R3

- 1Consultant General Surgery, King Fahad Hospital of the University, Saudi Arabia

- 2Immam Abdul Rahman Bin Faisal University, KSA, Saudi Arabia

- 3King Fahad Hospital of the University, KSA, Saudi Arabia

Received: October 1, 2018; Published: October 05, 2018

*Corresponding author: Nasser Mohammed Amer, MBBS, FRCS, Consultant General Surgery, King Fahad Hospital of the University, Assistant Professor, Immam Abdul Rahman Bin Faisal University, Al Khobar, KSA, Saudi Arabia

DOI: 10.32474/CTGH.2018.01.000119

Abstract

Mesenteric ischaemia is an uncommon condition with high mortality and morbidity, the causes can be embolic, thrombotic arterial or venous. Mesenteric venous thrombosis is an uncommon cause of bowel infarction, and it accounts for only 2-10% of the cases of Mesenteric Bowel ischaemia. We are reporting an interesting and uncommon case a fifty-year-old Filipina lady, not known to have any previous medical problems, presented to us with severe abdominal pain with minimal signs. Her CT scan confirmed Mesenteric Venous ischaemia and Bowel infarction. The lady was found to suffer from Protein C and S deficiency.

Keywords: Mesenteric Ischaemia; Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis; Bowel Infarction; Bowel Ischaemia; Thrombophilia

Introduction

Acute mesenteric ischaemia is an uncommon but very serious condition and carries very high mortality which may reach up to 50% [1], Mesenteric Venous Ischaemia (MVI) or Thrombosis (MVT) on the other hand accounts for 2- 10% of these cases. The reason behind the difficulty in diagnosing this problem lies behind its non-specific symptoms, low incidence and low awareness among clinicians [2], this attributes to its high mortality. The presentation of mesenteric bowel ischaemia ranges from chronic abdominal pain following meals (intestinal angina) to sudden severe pain due to embolic episode with hypotension and signs not correlating to the symptoms. Venous thrombosis is more insidious and unless bowel infarction has set up, can be treated medically using anticoagulation. Patients diagnosed with MVT should always be investigated for a background cause and screened for all types of thrombophilia. Those patients should also be closely followed up for their high susceptibility of developing deep venous thrombosis and Pulmonary embolism. They need to be anticoagulated for life.

Case Report

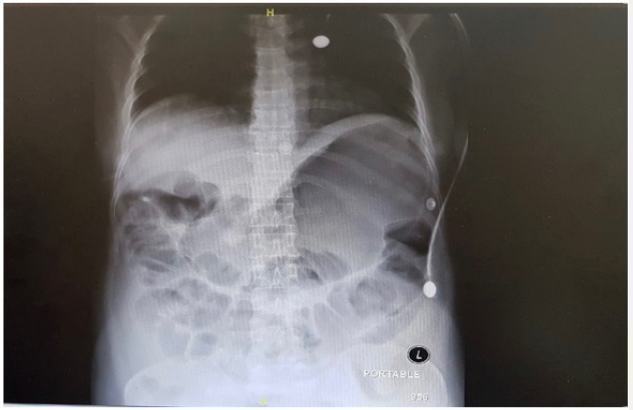

A fifty-year-old Filipina lady was referred to our surgical department because of severe vague abdominal pain started five days earlier and reached its crescendo at the time of assessment. The pain was persistent and progressive, radiating to her back. She gave history of vomiting several times, mainly of food content. Her bowel habits were normal, and she did not have any gynaecological symptoms, cardiac palpitations or any previous cardiac problem. On examination she looked very unwell, toxic, dehydrated. Her pulse was 143 per minute, regular, her blood pressure was 68/41, her Oxygen saturation was 85% on air, her respiratory rate was 25 per minute, and her temperature was 35.5. Her abdomen was slightly distended, soft but very tender, mainly centrally, with minimal guarding or rigidity. There were no palpable internal organs or signs of ascites, and bowel sounds were very poor. Aggressive fluid resuscitation was started with ringer lactate solution, 100% Oxygen and small dose of noradrenaline were also given. Her initial blood investigations showed a Hb of 10.6 gm, total leucocyte count of 46.7, Platelets of 192,000, BUN of 38 and creatinine of 2.7. Her lactic acid was 10.5. Rest of her electrolytes and liver function test were within normal range. Her plain abdominal XR Figure 1 showed dilated loops of small bowel, but nonspecific. Our initial impression was towards acute abdomen / peritonitis possible due to bowel ischaemia? perforated viscus? intestinal obstruction.

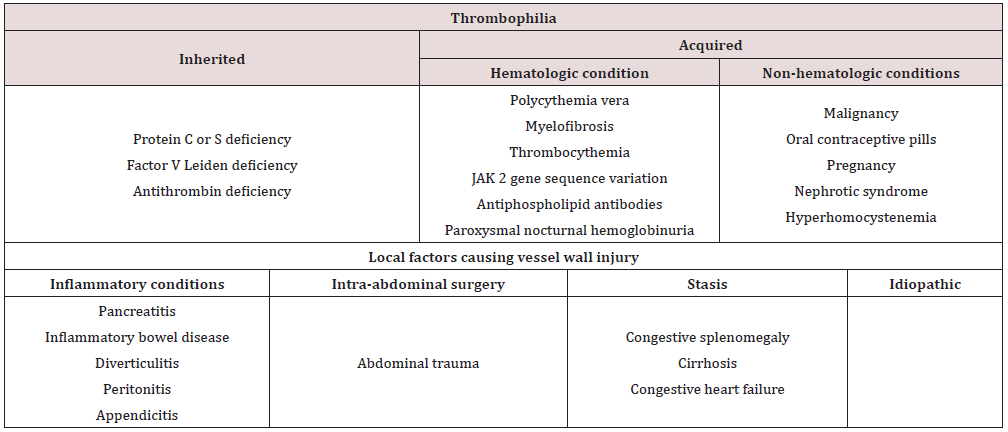

She had a CT scan (Figure 2) which confirmed the presence of Superior Mesenteric Vein occlusion and Portal Vein thrombosis with evidence of bowel ischaemia. Her clinical signs deteriorated, and she was taken to operating room where an exploratory laparotomy was done. This revealed ischaemic necrotic infarcted jejunal loop, about 137cm in length. Rest of the Bowel was normal. This segment was resected, and both ends of Jejunum were exteriorised in the form of jejunostomy and mucus fistula. Patient recovered well in the surgical intensive care unit. She had a normal cardiac echo, normal ECG, but screening for thrombophilia confirmed she had Protein C and S deficiency. Her Jejunostomy was reversed on day 7, during this time the viability of the ends were examined regularly, and she was put on intravenous heparin, which later was converted to warfarin after the second procedure. Patient developed Ileo femoral venous thromboses on the right side despite being anticoagulated. She was discharged on day 14 on warfarin.

Figure 2: CT scan with contrast showing thrombosis (arrow) in the portal Vein and Superior Mesenteric Vein.

Discussion

Acute mesenteric ischaemia is an uncommon pathology and almost always occur in the setting of pre-existing comorbidities, consequently mortality remains high, and approaches 50% [1]. This has not changed over the past four decades. Acute mesenteric ischaemia can be caused by thrombo-embolic occlusion of mesenteric arteries, 70% of which may follow a recent myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure or Digitalis therapy, previous emboli, hypercoagulable state or hypovolaemia and shock. Venous thrombosis, on the other hand, account for around up to 10% of the cases [1]and may follow hypercoagulable states in our case which turned out to be thrombophilia due to deficiency of protein C and S. Other causes include Portal hypertension, intra-abdominal inflammation, trauma and chronic Renal failure [1,3] see Table 1. The bowel can tolerate marked reduction in the blood flow, at rest 80% of the capillaries are not perfused without compromising adequate oxygen delivery [1]. During hypoperfusion, the intestinal mucosa can extract increasing amount of oxygen with preservation of its integrity, however prolonged ischaemia will produce an inflammatory reaction which disrupts the intestinal mucosal barrier and ultimately lead to translocation of the bacteria culminating in local and systemic inflammation, lactic acidosis, sepsis multi organ failure and possible death [3]. The ischemic visceral pain is intense and constant and does not increase with palpation. This results in the classic “pain out of proportion” sign [1]. Mesenteric Venous thrombosis on the other hand is usually superimposed by presence of malignancy, thrombophilia of which the most common is protein C or S deficiency [4,5] as in our case. A primary or idiopathic mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is when no underlying cause can be identified, this may account for up to 49% of the venous causes [3].

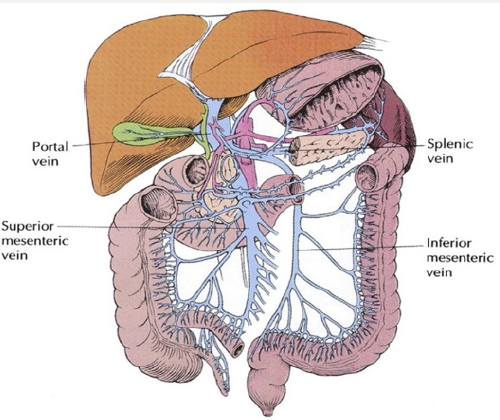

Unlike arterial thromboembolic event, where their presentation is sudden and may be preceded by symptoms of intestinal angina following meals, VMA usually present with vague abdominal pain not related to eating, diarrhoea and gastro intestinal bleeding [4]. Laufman [6] in an animal experiment demonstrated that ligating the main Superior mesenteric vein (Figure 3) only does not lead to bowel infarction. This category of patients will benefit from intravenous heparin. However, if the thrombosis extended to the vasa recta, bowel necrosis will follow [4]. Diagnosis of MVT can be confirmed by ultrasound in 75% of cases, however, CT with contrast is the imaging modality of choice due to high sensitivity (90-100%) [7], especially when it involves the SMV, splenic vein or portal vein [4]. Involvement of the inferior mesenteric vein is usually rare compared to the superior mesenteric vein. There are no accurate plasma biomarkers available for intestinal ischaemia. The fibrinolytic marker D-dimer has been reported to be a sensitive, but not specific, marker of acute thromboembolic occlusion of the SMA [2]. Thus, a normal D-dimer level can be used as an exclusion test for this diagnosis.

The management of ischaemic venous thrombosis with bowel necrosis ideally is damage control resection with stapler, or immediate resection and anastomosis, followed by second look in 24 -36 hours with anastomosis [1,7]. This allows reassessment of the integrity of the remaining bowel. However, in our case the decision to exteriorise rather than to do a damage control resection with stapler was because we expected our patient to take a longer time till she is optimised and ready for a second procedure, and by exteriorising the bowel ends we could monitor the integrity of both ends of the resected margins and to intervene if necessary if we felt that the necrosis is spreading beyond the margins. Medical management of MVT using anti-coagulation is possible when the initial diagnosis with CT scan was certain and bowel necrosis has not yet let to transmural infarction and perforation. This was concluded in a study of 26 patients [8] between 1987 – 1999. Anticoagulation will lead to recanalization of thrombosed veins, reducing the hospital stay, the mortality, the need for surgery and the risk of short bowel syndrome. If Rapid and complete occlusion of the mesenteric veins however, there may be insufficient time for development of a collateral circulation leading to transmural bowel infarction which may be compounded by arterial spasm [7]. The use of thrombolytic agents on the other hand was associated with high mortality up to 33%. Evaluation of the degree of bowel ischaemia using CT scan with contrast has always been difficult, however, measuring of the gastric mural pH and evaluating g the bowel thickness by contrast CT increased the accuracy in evaluating bowel ischaemia. This in addition to the finding of occlusion of second order radicals of SMV was more frequently observed in patient who needed bowel resection [9].

Patients treated conservatively with anticoagulation only, should receive prophylactic antibiotics, have complete bowel rest and total parental nutrition as absorption is usually impaired [7]. In conclusion, we emphasise the awareness of this pathology whenever we are presented with a patient presenting with bizarre abdominal symptoms, who looks unwell and his signs are out of proportion to his symptoms. CT with contrast is the best modality to confirm MVT, and if sure of absence of perforation or peritonitis, medical treatment with anticoagulation is possible.

References

- Michael J Sise (2014) Acute Mesenteric Ischemia. Surg Clin N Am 94: 165-181.

- Acosta S (2008) Epidemiology, risk and prognostic factors in mesenteric venous thrombosis. British Journal of Surgery 95: 1245-1251.

- Singal A, Kamath P (2013) Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis. Mayo Clin Proc 88(3): 285-294.

- Kumar S, Patrick S, Kamath S (2003) Acute Superior Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis: One Disease or Two? The American Journal of Gastroenterology 98(6): 1299-1304.

- Grisham A (2005) Deciphering Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis: Imaging and Treatment. Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 39(6): 473-479.

- Laufman H (1943) Gradual occlusion of the mesenteric vessels: Experimental study Surgery 13: 406-410.

- Paraskeva P, Akoh J (2015) Small bowel stricture as a late sequela of superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 6: 118-121.

- Antunes L (2001) Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis: Case for nonoperative management. Journal of Vascular Surgery 34(4): 673-679.

- El Kreif L (2014) Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus as a Risk Factor for intestinal Resection in Patient with Superior Mesenteric Vein Thrombosis. Liver International 34: 1314-1321.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...