Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1652

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1652)

Improvement of Liver Function by a Short-term Administration of Luseogliflozin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Single-arm Study and the Mini-literature Review Volume 3 - Issue 1

Koh Yamashita1* and Toru Aizawa1

- 1Diabetes center, Aizawa Hospital, Matsumoto, Japan

Received: March 15, 2021; Published: March 23, 2021

*Corresponding author: Koh Yamashita, Diabetes Center, Aizawa Hospital, 2-5-1 Honjo, Matsumoto, Japan

DOI: 10.32474/CTGH.2021.03.000156

Abstract

Background: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is not simply the hepatic manifestation of obesity and diabetes but also linked to hepatocellular carcinoma. Yet, its effective treatment has not been established. In this study, we evaluated the effect of a short-term administration of luseogliflozin to patients with type 2 diabetes having non-alcohol fatty liver disease. Luseogliflozin is a unique sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor which is metabolized in and excreted by the liver in addition to the kidney. Therefore, the drug might possess an additional effect on other agents of the same class which are exclusively metabolized in the kidney.

Methods: Using alanine aminotransferase >20 IU/L as a diagnostic basis for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, 19 patients, not taking alcohol, with type 2 diabetes (male/female 15/4, the median age 57 years) was treated with 2.5 mg luseogliflozin for 12 weeks.

Results: Pre- and post-treatment median values for alanine aminotransferase were 51 IU/L and 33 IU/L (p = 0.001), and the corresponding values for the fibrosis index based on the four factors [age (years) ∙ alanine aminotransferase (IU/L)] / [platelets (109/L) ∙ alanine aminotransferase (IU/L)1/2)] were 1.669 and 1.314 (p = 0.043). There was no adverse effect of the drug. Our findings were essentially compatible with the results of the previous studies reviewed.

Conclusion: We conclude that sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor could be the choice for the pharmacological treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Especially, a short-term administration of it is consistently effective in mild cases.

Keywords: SGLT2 inhibitor; NAFLD; Fibrosis-4 index; GPR-index; APRI.

Abbreviations: SGLT2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; GGT: gammaglutamyl transpeptidase; Fib-4 index: Fibrosis-4 index; GPR-index: gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase to platelet ratio; APRI: aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio

Introduction

Obesity or overweight is the motherland of non-alcoholic fatty

liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)

[1]. Accordingly, with increasing trend of body weight worldwide,

the number of patients with the liver problem is relentlessly

increasing [2]. Recently, NASH has also been attracting the attention

as a cause of hepatoma [3,4]. Under such yet, treatment of NAFLD

(NASH and NAFLD are collectively called NAFLD hereafter in this

communication), irrespective of presence or absence of diabetes,

has not been established. Results of treatment of patients with

type 2 diabetes (T2DM) having NAFLD with sodium-glucose cotransporter-

2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) appears promising [3-7], the

effectiveness of a short-term treatment, such as 12 week-treatment,

has not been established.

Here, we evaluated effectiveness of a short-term administration

of SGLT2i, luseogliflozin, that is metabolized not only in the kidney

but in the liver [8]. A mini literature review on this issue was also performed to resolve the current inconsistency. This study was

approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aizawa

Hospital (No. 2019-094).

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Consecutive 29 patients with T2DM who took luseogliflozin

for 3 months or longer between January 1, 2019 to May 31, 2020

were initially registered. Because the purpose of this study was

to investigate the effect of luseogliflozin on NAFLD/NASH, 8 with

alanine aminotransferase (ALT) less than 20 IU/L [9], and other 2

with a habitual alcohol drinking of 20 g/day or more were excluded,

and the remaining 19 were analyzed.

The study was a single-arm, add-on study. Namely, 2.5

mg luseogliflozin was additively prescribed on top of the

hypoglycemic agents already taken by the patients, which are

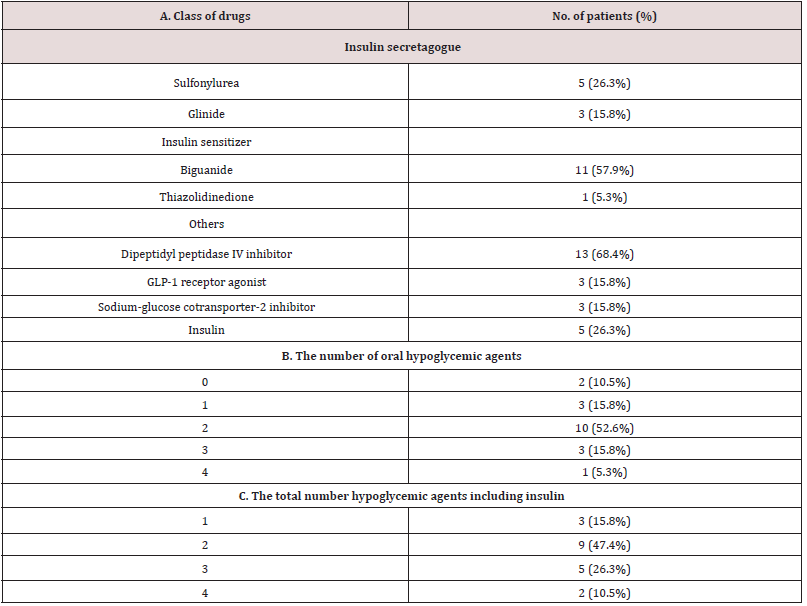

shown in Supplemental Table 1. The data before and 12 weeks after

luseogliflozin administration was critically compared.

Laboratory measurements

In addition to the routine clinical chemistries, indices of the hepatic fibrosis including Fibrosis-4 index (Fib-4 index), gammaglutamyl trans peptidase (GGT) to platelet ratio (GPR-index), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio (APRI) were calculated10: the unit for AST, ALT, GGT as IU/L, platelet counts as 109/L and age as a year. Equations for each index were as follows [10].

Fib-4 = [(AST) ∙ (age)] / [(Platelet counts) ∙ (ALT)1/2]

GPR index = 100 ∙ (GGT) / (Platelet counts)

APRI = 100 ∙ (AST) / (Platelet counts)

Statistical analysis

The data were collected retrospectively and analyzed cross-sectionally and longitudinally. We evaluated the effect of luseogliflozin on the liver function tests and the indices of liver fibrosis. In addition, delta, i.e., the basal value minus 12 week-value for the indices of liver fibrosis was calculated for each study subject, and correlation between the delta values of fibrosis indices and the basal plasma glucose (PG), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), AST, ALT, GGT, body weight (BW) and body mass index (BMI) were examined. Furthermore, the delta value of the liver fibrosis indices and the delta value of PG, HbA1c, AST, ALT, GGT, BW and BMI were also examined. The statistical analysis was performed using JMP ver.15. Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Wilcoxon signed rank test and Spearman rank correlation were used as needed.

Literaturereview

Representative 10 original reports published in the English language on the treatment of patients with T2DM having NAFLD by SGLT2 inhibitors [6,7,11-18] were summarized to provide a current overview of the issue. In these literature, five kinds of SGLT2i agents were prescribed, with the number of the patients ranging from 9 to 32 and the treatment duration from 12 to 48 weeks.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the patients

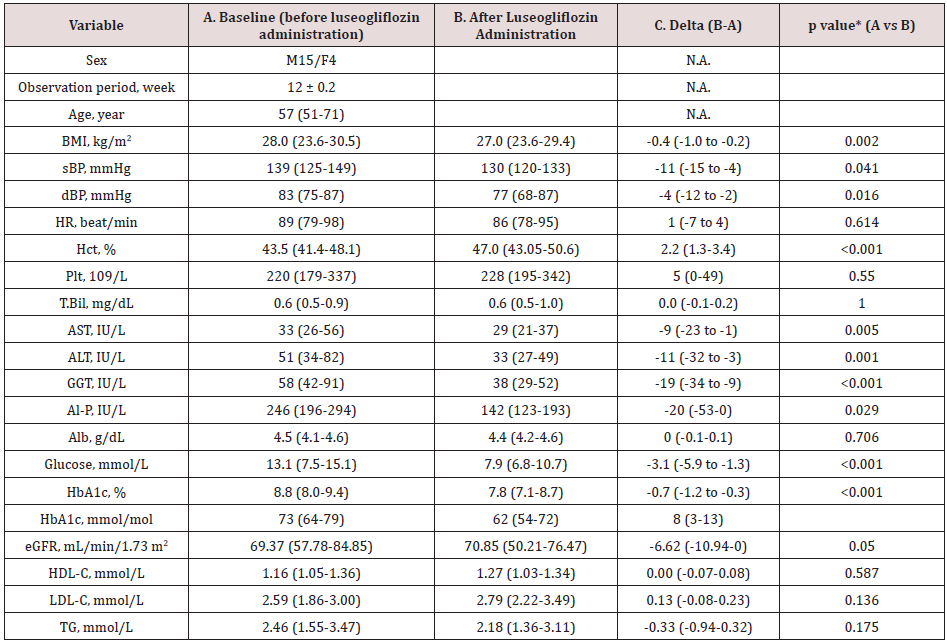

Table 1. Baseline data (A), the data 3 months after the luseogliflozin treatment (B) and the difference (C) between the two (luseogliflozin- basal).

Values are median and interquartile ranges except for sex and the observation period: the latter was shown as mean and SD. sBP, systolic blood pressure; dBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; Hct, hematocrit; Plt, platelet count; T.Bil, total bilirubin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; Al-P, alkaline phosphatase; Alb, albumin; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C, high density-lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density-lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides. N.A., not applicable. *Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

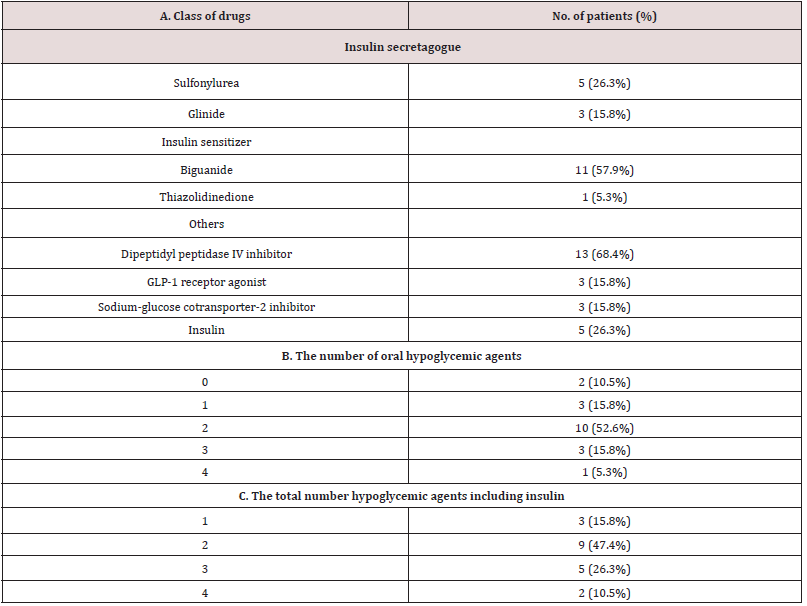

The study patients were male dominant (the proportion of males, 79%), middle-aged Japanese adults with the median BMI of 28.0 kg/m2 which was larger than the representative value in the Japanese patients with T2DM in general11(Table 1A). The median HbA1c value of the entire group before luseogliflozin was 8.8% (77 mmol/mol) so that the level of glycemic control was unsatisfactory (Table 1A). Regarding the hypoglycemic agents used before subscribing luseogliflozin, Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and biguanide were most frequently employed (Supplemental Table 1), which was typical for the Japanese patients [19].

Supplemental Table 1: Medications before administration of luseogliflozin. 2.5 mg luseogliflozin was added in each patient on top of the medication described above.

Values are median and interquartile ranges except for sex and the observation period: the latter was shown as mean and SD. sBP, systolic blood pressure; dBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; Hct, hematocrit; Plt, platelet count; T.Bil, total bilirubin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; Al-P, alkaline phosphatase; Alb, albumin; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C, high density-lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density-lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides. N.A., not applicable. *Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Liver function and indices of hepatic fibrosis following luseogliflozin administration

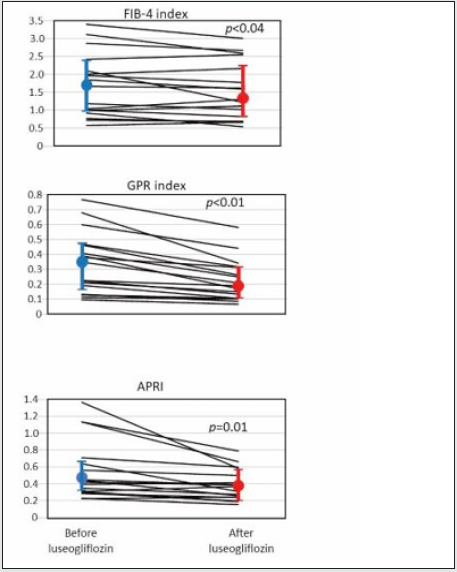

Elevated serum level of ALT was an inclusion criterion, so that the ALT was clearly elevated as a group with the median value, 51 IU/L. As well expected, administration of luseogliflozin significantly decreased PG and HbA1c (Table 1, A and B, before and after luseogliflozin, respectively). In addition, it significantly lowered the serum level of AST, ALT, GGT, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). The degree of lowering was 12%, 34%, 35 and 42% for the respective enzyme levels. Importantly, the luseogliflozin treatment also significantly lowered the values for Fib-4 index, GPR index, and APRI (Figure 1).

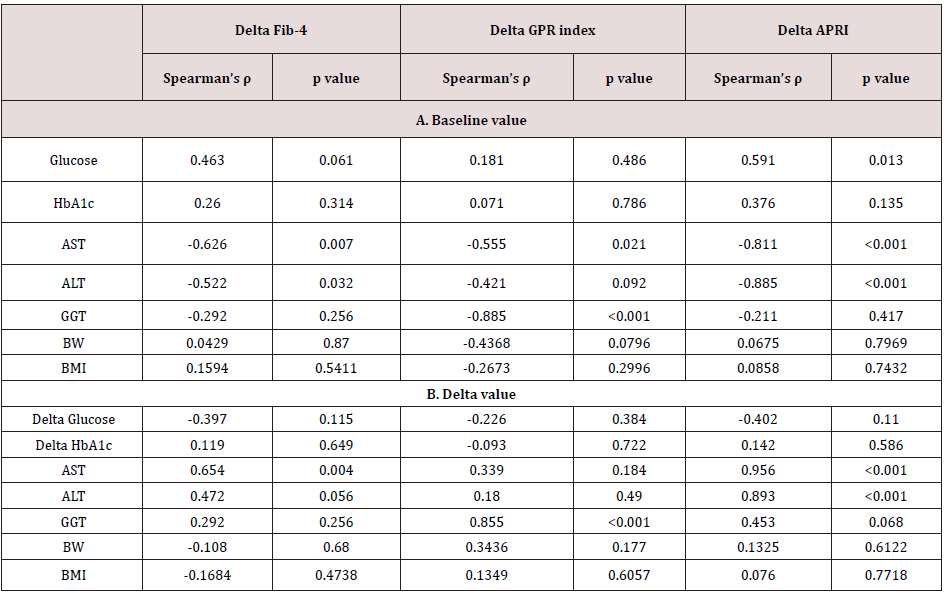

Correlation between delta Fib-4, GPR index, and APRI and baseline and delta values of liver function and the body weight and BMI

Figure 1: Change of indices of liver fibrosis produced by luseogliflozin. Individual lines represent a change of the value in each person and the circles, and the vertical lines indicate the median and interquartile ranges: blue ones for before and red ones for after luseogliflozin. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for the statistical analysis.

The delta Fib-4 index was significantly and positively correlated

associated with higher baseline AST and ALT levels; the delta GPR

index was correlated with baseline AST and GGT; the greater delta

APRI was associated with higher baseline AST and ALT (Table

2A). Correlation between the delta values and the baseline of liver

function was absent for BW and BMI (Table 2A).

On the other hand, there was an inverse correlation between

‘delta Fib-4 and delta AST and delta ALT’, ‘delta GPR index and delta

GGT’ and ‘delta APRI with delta AST and delta ALT’ (Table 2B).

There was no significant correlation between delta values of the

fibrosis indices and the delta of BW and BMI (Table 2B).

Table 2. Correlation between delta Fib-4, GPR index and APRI and baseline value (A) and delta (B) of liver function. Delta means the difference between the value of each test performed on the day of starting luseoglifrozin and 12 weeks later.

Values are median and interquartile ranges except for sex and the observation period: the latter was shown as mean and SD. sBP, systolic blood pressure; dBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; Hct, hematocrit; Plt, platelet count; T.Bil, total bilirubin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; Al-P, alkaline phosphatase; Alb, albumin; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C, high density-lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density-lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides. N.A., not applicable. *Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Literature review

In the previous studies, SGLT2i was administered for the relatively small number of patients with type 2 diabetes having NAFLD (up to 32) for the relatively short period (up to 48 weeks) for patients with T2DM having NAFLD (Table 3). In general, the agent effectively ameliorated the hepatic fat accumulation as indexed by the liver function tests, the fibrosis indices, the morphological tests such as computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or biopsy. However, the detailed analysis of the reported data of the short-term therapy exhibited inconsistency. According to the report by Eriksson JW et al [7], in one population with the treatment duration of 12 weeks, liver function was improved and fat accumulation in the liver decreased, and in the other, the hepatic fat was not decreased by the 12 weektreatment with SGLT2i [7]. Morphological evaluation of the liver was not carried out in the third study [14]. Taken together, twentyfour weeks was the shortest period needed to firmly demonstrate improvement of hepatic morphology indicating attenuation of fat accumulation [12,17]. No clear-cut difference on the basis of species of SGLT2i was observed.

Table 3. Literature reporting the effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor on the liver in patients with type 2 diabetes having fatty liver. Tx, treatment; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OM-3CA, omega-3 carboxylic acid; N.D., not done. Ref. 6 was a two-arm study. TBA, to be announced if this communication is accepted.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed effect of 2.5 mg luseogliflozin given for 3 months to patients with T2DM having NAFLD, judged by ALT 20 IU/L or higher. We confirmed the substantial lowering, generally 30-40%, of elevated liver enzyme levels and, moreover, decrease in the established indices of liver fibrosis such as Fib-4 index, GRP index, and APRI, by this short-term SGLT2i treatment in the group. Elevated delta Fib-4 was significantly associated with higher basal Fib-4 values, and as expected from the definition of Fib-4, delta Fib-4 and delta AST well correlated each other. The degree of improvement of the indices of hepatic fibrosis was much less than that of glycemia, and our preliminary data suggested that lowering of delta Fib-4 correlated with improvement of insulin sensitivity indexed by lipids and BMI [20] (data not shown). Absence of correlation between the drug effect on the indices of fatty liver and its effect on the BW strongly suggested that BW reduction was not the primary conveyer of SGLT2i’s favorable effect on NAFLD, at least under our treatment protocol. Importantly, the average change of the three fibrosis indices corresponded to the range observed in patients whose alteration of the hepatic fibrosis proven by biopsy or ultrasonography [10]. A significant lowering of Fib-4 after treatment with SGLT2i was not recognized in some of the previous studies (Table 3). A clear-cut luseogliflozin effect within a short period on the liver in our study might be due to the stringent selection of study participants using ALT ≥ 20 IU/L as an entry criterion. The mini review can be summarized as, 1) favorable outcome of SGLT2i treatment on NAFLD may be a class effect, 2) the hepatic enzymes may be relatively sensitive as indicators of improved NAFLD showing significant attenuation within 12 weeks, and 3) for measurable reduction of hepatic fat, approximately 10 more weeks of luseogliflozin treatment are needed. Hepatic triglycerides (TG) accumulation might be excessively stimulated by an abundance of substrate, hyperglycemia, and hyperinsulinemia in T2DM patients with NAFLD [21], and SGLT2i might suppress this circle by lowering PG and serum insulin at the same time through improved insulin sensitivity [22,23]. Results of randomized, largescale, prospective studies with measurements of insulin and newer markers are strongly awaited to fully understand the significance of SGLT2i in NAFLD or NASH.

Conclusion

Short-term (twelve-week) add-on administration of luseogliflozin lowered plasma glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes having NAFLD. In addition, the treatment effectively suppressed markers of fatty liver likely through improved insulin sensitivity. Through the literature review, luseogliflozin’s effect on fatty liver appears to be comparable to other SGLT2i.

References

- Younossi Z, Anstee Q, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, et al. (2018) Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 8(15): 11-20.

- Dewidar B, Kahl S, Kalliopi Pafili K, Michael R (2020) Metabolism 111: 154299.

- Arab JP, Dirchwolf M, Álvares-da-Silva MR, Barrera F, Benítez C, et al. (2020) Latin American Association for the study of the liver (ALEH) practice guidance for the diagnosis and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol 19(6): 674-690.

- Marengo A, Rosso C, Bugianesi E (2016) Liver cancer: Connections with obesity, fatty liver, and cirrhosis. Annu Rev Med 67: 103-117.

- Scheen AJ (2019) Beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on fatty liver in type 2 diabetes: A common comorbidity associated with severe complications. Diabetes Metab 45(3): 213-223.

- Ito D, Shimizu S, Inoue K, Saito D, Yanagisawa M, etal. (2017) Comparison of Ipragliflozin and Pioglitazone effects on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: A Randomized, 24-week, open-label, active-controlled trial. Diabetes Care 40(10): 1364-1372.

- Eriksson JW, Lundkvist P, Jansson PA, Johansson L, Kvarnström M, etal. (2018) Effects of dapagliflozin and n-3 carboxylic acids on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in people with type 2 diabetes: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia 61(9): 1923-1934.

- Hasegawa M, Chino Y, Horiuchi N, Hachiura K, Ishida M, etal. (2015) Preclinical metabolism and disposition of luseogliflozin, a novel antihyperglycemic agent. Xenobiotica 45(12): 1105-1115.

- Kunde SS, Lazenby AJ, Clements RH, Abrams GA (2005) Spectrum of NAFLD and diagnostic implications of the proposed new normal range for serum ALT in obese women. Hepatology 42(3): 650-656.

- Lemoine M, Shimakawa Y, Nayagam S, Khalil M, Suso P, etal. (2016) The gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase to platelet ratio (GPR) predicts significant liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic HBV infection in West Africa. Gut 65(8): 1369-1376.

- Ohki T, Isogawa A, Toda N, Tagawa K (2016) Effectiveness of ipragliflozin, a sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, as a second-line treatment for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who do not respond to incretin-based therapies including glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Clin Drug Investig 36(4): 313-319.

- Shibuya T, Fushimi N, Kawai M, Yoshida Y, Hachiya H, etal. (2018) Luseogliflozin improves liver fat deposition compared to metformin in type 2 diabetes patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A prospective randomized controlled pilot study. Diabetes ObesMetab 20(2): 438-442.

- Akuta N, Watanabe C, Kawamura Y, Arase Y, Saitoh S, etal. (2017) Effects of a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease complicated by diabetes mellitus: Preliminary prospective study based on serial liver biopsies. Hepatol Commun 1(1): 46-52.

- Kuchay MS, Krishan S, Mishra SK, Farooqui KJ, Singh MK, etal. (2018) Effect of empagliflozin on liver fat in patients with type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial (E-LIFT Trial). Diabetes Care 41(8): 1801-1808.

- Seko Y, Nishikawa T, Umemura A, Yamaguchi K, Moriguchi M, et al. (2018) Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic steatohepatitis classified as stage 1-3 fibrosis. Diabetes MetabSyndrObes 11: 835-843.

- Inoue M, Hayashi A, Taguchi T, Arai R, Sasaki S, etal. (2019) Effects of canagliflozin on body composition and hepatic fat content in type 2 diabetes patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Diabetes Investig 10(4): 1004-1011.

- Kinoshita T, Shimoda M, Nakashima K, Fushimi Y, Hirata Y, etal. (2020) Comparison of the effects of three kinds of glucose‐lowering drugs on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, open‐label, three‐arm, active control study. J Diabetes Investig 11(6) 1612-1622.

- Lai LL, Vethakkan SR, Mustapha NR, Mahadeva S, Chan WK (2020) Empagliflozin for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Dig Dis Sci. 65(2): 623-631.

- Japan medical association diabetes database of clinical medicine, J-DOME report 2nd edition, 2020.

- Paulmichl K, Hatunic M, Højlund K, Jotic A, Krebs M, etal. (2016) Modification and validation of the triglyceride-to-HDL cholesterol ratio as a surrogate of insulin sensitivity in white juveniles and adults without diabetes mellitus: The Single Point Insulin Sensitivity Estimator (SPISE). Clin Chem 62(9): 1211-1219.

- Chao HW, Chao SW, Lin H, Ku HC, Cheng CF (2019) Homeostasis of glucose and lipid in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci 20(2): 298.

- Merovic A, Solis-Herrera C, Daniele G, Eldor R, Fiorentino TV, etal. (2014) Dapagliflozin improves muscle insulin sensitivity but enhances endogenous glucose production. J Clin Invest 124(2): 509-514.

- Ferrannini E, Muscelli E, Frascerra S, Baldi S, Mari A, etal. (2014) Metabolic response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Invest 124(2): 499-508.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...