Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-6062

Review Article(ISSN: 2638-6062)

The Gender Perspective in Forensic Identification Processes in Mexico: Invisibility of Transsexual Women Volume 5 - Issue 1

Isabel Beltrán Gil*

- Member of the Coordination Assembly and Research Committee of the Social and Forensic Anthropology Research Group (GIASF), Mexico

Received: April 27, 2023; Published:May 04, 2023

*Corresponding author: Isabel Beltrán Gil, PhD, Member of the Coordination Assembly and Research Committee of the Social and Forensic Anthropology Research Group (GIASF), Mexico

DOI: 10.32474/PRJFGS.2023.05.000201

Abstract

Gender diversity refers to the variety of gender identities, expressions and roles that exist beyond the traditional categories of “masculine” and “feminine”. This includes people who identify as male, female, non-binary, transgender, intergender, and other. Recognizing and respecting gender diversity is essential to encourage equality and non-discrimination. For this reason, the gender perspective is promoted as a necessary tool in the execution of forensic search and identification processes. However, there is still a long way to go to be able to consider that the forensic field has fully integrated into this approach. This reality invites us to reflect on the mechanisms, tools, methodologies, and challenges that currently exist around gender diversity, the disappearance of people and forensic identification.

Keywords: Lophoscopy; forensic genetics; forensic odontology; medicolegal necropsy; forensic anthropology

Introduction

Gender refers to social concepts related to roles, behaviors, activities, and attributes that each society and culture consider to be appropriate for men, women, and people with non-binary identities [1]. This reality contributes to the need to understand gender diversity. In this regard, it should be understandable to everyone that gender diversity refers to all the possibilities that a person must assume and express their identity beyond the binary categories of “masculine” and “feminine”. For this reason, talking about diversity becomes an essential instrument to be able to encourage both equality and non-discrimination. This objective is what promotes acting with a gender perspective in all areas of social life. It represents a tool that makes it possible to identify, question and assess the presence or absence of discrimination, inequality and exclusion based on gender. For this reason, in many countries, such as Mexico, it is urged to carry out a search and identification from this perspective. So that standards are established that do guarantee the right to be duly searched for and identified without the identity of a person implying a divergence in access to all existing human rights. However, it is relevant to question whether this approach has been fully integrated in the forensic field.

Gender Perspective in Search Processes

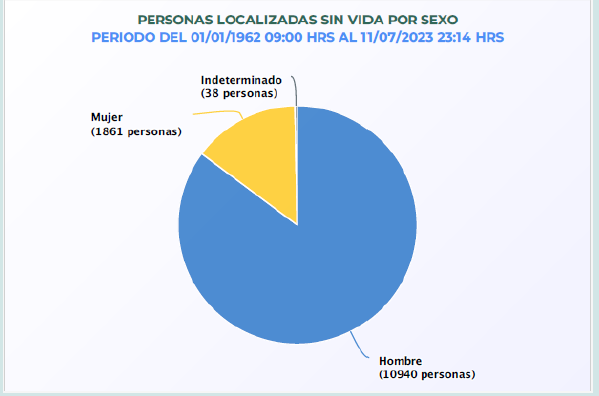

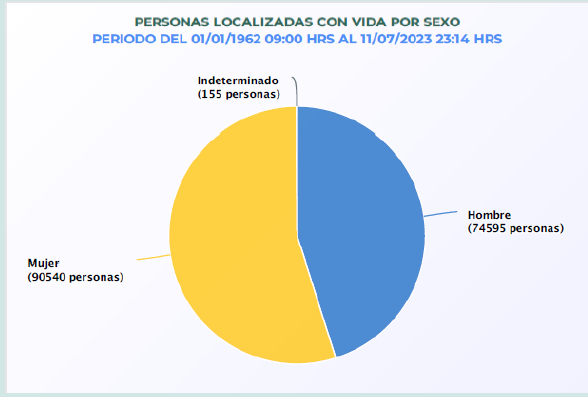

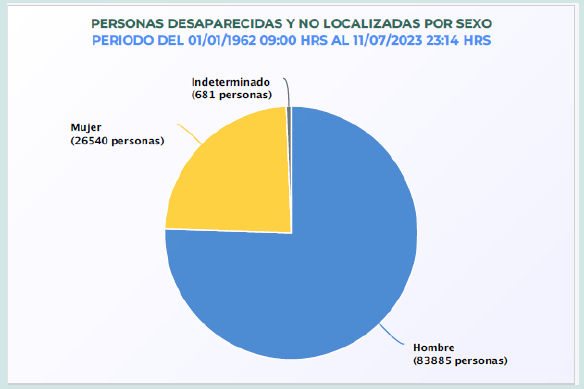

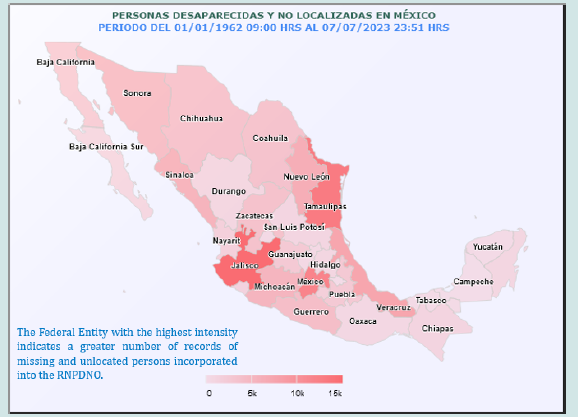

Gender includes a wide diversity of people with very different social, economic, and political problems that require visibility and effective implementation of solutions. Therefore, having a binary approach when you analyze disappearances leads to a biased analysis of the context, thus limiting the identification of patterns and types of violence. In countries like Mexico, the gender approach is already incorporated as the guiding principle of its Approved Search Protocol (2020). In its narrative, it establishes that the authorities in charge of the search have a reinforced duty when the victim of disappearance belongs to the population of sexual diversity, or when it concerns the disappearance of a person due to their gender identity. Nevertheless, in Mexico, the analysis of the context and statistics related to disappearances continue to present a binary scheme, which makes it difficult to measure the existing violence owing to gender issues (Figure 1). Establishing a dichotomous classification based solely on biological parameters (sex) makes it difficult to correctly develop the gender perspective as a transversal axis in all search and investigation actions, since this problem is not made visible from the gender identity of the victims.

Bibliographical source: https://versionpublicarnpdno.segob.gob.mx/Dashboard/ContextoGeneral

Taking this diversity into account and capturing it in statistical analyzes represents the real possibility of carrying out a systematic examination of violence based on the attribution of a sexual identity, sexual orientation, and gender identity. This could be a more effective and efficient way of carrying out a context analysis that helps in the search and investigation processes, in addition to contributing to the formulation of more effective and concrete public policies. In the figure 3 above, it can be seen how when referring to missing and unlocated persons, one speaks specifically of a statistic by sex, leaving as not indeterminate those persons who are not classified by this biological category (specifically 682 indeterminate), a situation which is repeated in the graph of people located alive (15 people of indeterminate sex) and in the case of people located (figure 1) where there are 38 individuals. (Bibliographical source: https://versionpublicarnpdno.segob. gob.mx/Dashboard/ContextoGeneral). Under these parameters, it can be observed that there is still a depth of inequality and discrimination based on gender, which has a disadvantageous effect for the victims of forced disappearance or disappearance by individuals who do not identify themselves under the prevailing binary and heterosexual norm. They remain invisible within this serious problem that is disappearance. In this sense, the lack of forensic strategies in the search and identification that reflect the challenges that gender diversity implies can only contribute to preserving and increasing the prevailing forensic crisis in Mexico.

Trans femicide, Feminicide Due to Gender Identity, Disappearance, and Forensic Crisis in Mexico

The mobilization of sexual dissidents has achieved social recognition of different gender identities. This diverse group includes transgender people, that is, those who do not feel represented by the gender they were assigned at birth. The term trans often refers to people who have transitioned from one socially binary gender to another (male to female or female to male) and is very often the target of aggression, marginalization, and prejudice. Added to this violence is even disappearance [2], and here it must be kept in mind that the challenges involved in searching, locating, and identifying increase with gender diversity. In particular, trans women are immersed in a cycle of violence and discrimination that has led them to be victims of trans femicide or femicide due to gender identity. In this sense, the report on violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex (LGBTIQ+) persons from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights records that most murdered trans women are under 35 years of age [3]; and that, for example, Mexico ranks second in the world with the highest number of registered murders of trans people [4]. This reality points to the need to adapt the elements for the search, location, identification, and restitution of disappeared persons. Consistent with this, a review of the Ante-Mortem (AM) records, also known as Life Records, and the methods used for identification is required [5]. So, the gender perspective is present as a guiding axis of all the identification systems that are currently used.

General Information about Identification Systems

People identification systems are procedures derived from different disciplines in which various methods and techniques are used to establish the identity of a living or dead person or their human remains. This is done by determining the set of characteristics and traits that distinguish one person from another. Therefore, identification is based on the principle that no two things are the same in the world. Thus that identification allows us to assert that every single being is equal to herself/ himself and cannot be equal to another, except in the case of monozygotic twins. Human identification systems allow us to establish the identity of the probable perpetrators and the victims in the commission of a crime. This implies a correct approach to the context, adequate processing of the place of discovery, of the located and collected evidence, as well as an interdisciplinary analysis of the people involved. Among the precursor procedures of human identification are the spoken portrait, photography, anthropometry and dactyloscopy, for instance. It must be taken into account that in the beginning these procedures could be questionable due to their lack of precision, but they are the precedents for the identification system that is used today in forensic cases.

Scientific research has been responsible for the gradual and continuous improvement of these tools, providing greater precision and reliability in their results, which is why they are still used today, even if sometimes as an auxiliary resource to generate identification hypotheses. Human identification can be applied in cases where the person to be identified is alive or dead, and each of these cases presents different degrees of complexity. Specifically, in scenarios where the person is lifeless, more advanced systems and greater human, technological and economic resources are required because the decomposition process and the state of conservation of the skeleton are subject to many variables and conditions. Knowing the different types of identification systems that currently exist is relevant from a gender perspective. Identifying from this perspective entails considering whether gender represents a visible and analyzable trait from the corporal component. Thus, when analyzing each of the disciplines that participate in identification, it can be stated that not all of them have the capacity to provide information that allows for gender analysis as part of the individualizing traits. Nevertheless, the tools used by some of these identification systems can help with this objective, such as X-rays or tomography’s for example. The Minnesota protocol [6] and the protocol for forensic treatment and identification of Mexico [7] point out among their pages the value that radiographs have in identification, however, it is presented as an optional and not mandatory tool.

Feminization and masculinization surgeries will not always be detected if the X-ray film is not established in the protocols as a mandatory method in the analysis. When the body is completely skeletonized it is much easier to observe and document the alterations produced on the bone and the presence of implants, plates, or screws because of an aesthetic procedure. The problem lies when the body still has tissue and the autopsy, due to overload in the Forensic Medical Services (SEMEFOS), does not consume the recommended time or the techniques described in the Minnesota protocol. Giving rise to this situation leads to the loss of relevant and significant information for identification. In this same context, the problem increases when the body shows the effects of the decomposition process, making it more difficult or even impossible to identify particular signs in the soft tissue, such as scars from plastic surgery. Talking, therefore, about the gender perspective in identification implies being aware of the different challenges that each identification system must overcome. So, for example, for the field of forensic medicine, a protocol with a gender approach has to consider and explain the value of X-rays as an instrument that makes it possible to identify and analyze certain body modifications. Nevertheless, for these updates in the identification systems to contribute to this objective, a readjustment in the Ante-Mortem (AM) records is required.

Gender Diversity in the Ante-Mortem (AM) File

The objective of the questionnaires is to collect all the information related to the disappeared person to identify him / her. Therefore, these sheets contain many questions related to:

a) Physical characteristics (which refers to the physical features of a person such as the shape of the eyebrows, the size of the mouth and even the appearance of the teeth, among others).

b) Pathologies (which refers to both physical and mental illnesses that a person can suffer, and that would help both in the search and in the identification).

c) Injuries (correspond to any change or damage that occurs in any part of the body. These include bone fractures which are an important factor in the identification process).

d) And finally, questions related to individualizing aspects (for example, scars, tattoos, birthmarks, etc.).

However, in the most common modalities of this type of record, gender identity and gender expression are not considered significantly among the questions that make up the questionnaire. Thinking about gender diversity and specifically about trans people requires asking questions that look at their identity from a biological and social perspective. For this purpose, the form must request information on the sex given at birth and the gender identity with which the person identifies (which includes the name with which they are registered in the population register and the name with which they identify based on their gender identity), so that this information is included in all the documents necessary for the search and identification (from the complaint to the AM file and, in the case of a corpse, integrated report). We must consider that the lack of consistency in this information can make it difficult to locate, identify and return them with dignity (Beltrán-Gil 2020).

In addition, questions should be asked that consider body modifications that facilitate the transition between binary sexes, including genital surgery and facial feminization or masculinization surgery, without forgetting hormone replacement therapy. Limiting the data to the structure of the biological profile (sex, age, height) means that the victims of extreme violence are not representative of the general population. In the same way, the description of the articles of clothing can represent a gender expression, hence the importance of recording this information in detail both in the antemortem file and in the post-mortem file. Clothing can speak of identity, so finding a biologically male skeleton, but wearing female clothing, may be representing gender expression. This information must be treated as part of the identification hypotheses that are handled in these processes. However, the clothing found on the body of the victim or at the place of discovery is not treated under the specifications of the chain of custody protocol [8]. On many occasions, its collection, analysis, and storage in the evidence warehouse is discarded. Generally, the clothing items that accompany unidentified persons are lost, discarded, or buried along with the body, which compromises their integrity [9].

The Gender Perspective in The Anthropological Process of Identification

Nevertheless, having an AM questionnaire that contemplates these body modifications is of little use if, for example, anthropology does not implement updates in its protocols and action manuals, in order to present a true gender perspective, where the objective of analyzing the human remains is not limited to determining sex. Modifications made to the skeleton and soft tissue during transition surgeries are intended to mimic “male” or “female” morphology. For example, feminization surgery corresponds to a group of surgical procedures intended to feminize the faces of people transitioning from male to female. Specifically, the specific procedures that directly impact the facial skeleton are:

a) The contour of the forehead or frontoplasty

b) Rhinoplasty.

c) The contour of the chin.

d) The contour of the jaw.

e) And the reduction of Adam’s apple.

Hence, we must bear in mind that each of these procedures will represent a different challenge for observation and interpretation. For example, the female frontoplasty can be performed through three ways. In the first place, it can be used through an implant to improve the curvature of the profile and these implants can be with injectable material, fat grafting or with a permanent implant. Therefore, we can already intuit the difficulties and challenges that may arise to detect this first type of frontoplasty. A second procedure consists of scraping the frontal bone with a contour drill, reducing the bone approximately 3 to 5 millimeters. Due to the characteristics of this intervention, we can assume or ask ourselves: in the case of complete skeletonization, will it be possible to observe or detect these scratch marks on the bone? or will they be visible through an x-ray or a CT scan? And the challenge really lies in the implementation of research that helps answer these questions, to create a methodology or technique that is useful in the forensic framework.

The third type of frontoplasty is performed by removing and replacing the frontal sinus wall, then adjusting the area surrounding the frontal sinus bone and reshaping the forehead with a titanium microplate that is fixed with screws. As can be seen, this procedure is very invasive and therefore easily detectable when the body is skeletonized. Now, if the soft tissue is still present, the detection of this surgery will be visible in case of resorting to x-rays, topographies or lifting of the facial tissue as part of the autopsy procedure, without forgetting the examination of the body prior to the intervention to point out and document any particularity, such as the scar on the scalp, specifically behind the hairline, which would be present as part of this surgical procedure. For its part, chin feminization surgery, which is usually carried out in combination with jaw remodeling, seeks to achieve fewer square shapes in the chin. To achieve this objective, milling or filing of the bone is performed, depending on the surgeon, the technique used may or may not be ultrasound to address the bone without affecting the soft tissue.

As part of this procedure, the length, width, and placement of the chin can be altered by modifying its projection. Therefore, the focus of facial feminization surgeries is found in modifying the craniofacial markers that anthropologically allow to determine the sex of an adult person. Now, does the presence of these facial modifications with the aim of feminizing the skeleton necessarily imply that it is a trans person? The truth is that no, because this type of surgery is also performed by cisgender women who want to refine their facial features and this reality increases the challenge and the need to implement research with a gender approach in the identification process. These modifications to the skeletal morphology to transition can only be made in the cranial region, thus changes in the pelvic contour are closely related to the use of implants. The pelvic bone does not undergo any direct alteration. Thus, a comparative analysis between the skull and the pelvis can speak of cosmetic surgeries performed on a cisgender woman, or surgeries focused on the trans population.

Science and Gender; A Path for Identification with A Gender Perspective

It is important to begin a discussion and understand how these surgeries may impact assessment of cranial sex, and ultimately update the forensic gaze to assess both sex and gender as part of the forensic skeletal profile. And here it must be recognized that it is a subject that is currently very little explored by forensic anthropology, which is why the need to implement research and methodologies that specialists can implement in their studies is suggested. And, among these investigations, it is also worthwhile, for example, to study the effects that hormone replacement treatments can have on the skeleton depending on the age at which the consumption of these hormones begins. For example, there are studies related to postmenopausal patients who use estrogen supplements alone or in combination with progestogens, obtaining various results related to changes in bone density or the risk of fracture and contraindications, among others [10-12]. To cite other research would be the work of Landa that analyzes the role of hormone replacement therapy in the prevention and treatment of menopausal osteoporosis [13]. Hence, as we can see, works whose object of study are hormonal treatments already exist, but they are focused on a very specific problem that is the effects of menopause, therefore, it contemplates a very specific population and a very limited period of the consumption of these substances.

More work is needed, such as that of Stowell and colleagues [14] that talks about the bone health of trans adults and everything that a radiologist needs to know about it for the interpretation of the images, because these studies have a very significant importance for the process’s identification. Similarly, there is research by Adbala and associates focusing on studying bone health in trans people [15]. Another example can be the study carried out by Dr. Calvar and colleagues that talks about the concerns related to the complications or sequelae that hormone treatment can have, especially in cases where treatment begins at an early age, and more taking into consideration that they must ingest these hormones continuously throughout their lives [16]. But it is still necessary to delve into the effects that it can have on the skeleton, and by this, I mean about the sexual markers that are present in the skeleton, when he / she starts hormone treatment at an early age, that is, before sexual maturation. The use of injectable material as a mechanism to change the morphology of the body also requires in-depth studies. Transition surgeries and treatments are subject to socioeconomic issues. Thus, the quality of the materials used for these interventions entails in some cases significant effects that must be known. This makes a necessary investigation from the social perspective.

Conclusion

Therefore, it is evident that there is a very vast field of study, and it is necessary to incorporate gender as part of the identification process. However, the challenge is to have access to a skeletal collection of the trans population that allows all these investigations to be carried out. And, although this absence can be filled from tomographic collections representing the before and after surgical processes of gender transition, as some researchers who have begun to work on this topic have already done, some difficulties are still present that they are outlined in the access to this resource to carry out the study, and the implementation of its results to real contexts where the body or skeleton will be worked directly. Despite these limitations, we cannot forget that gender violence is a problem that is on the rise in Mexico and other Latin American countries and is registering an increasing number of femicides and trans feminicides. This represents an urgent call to review strategies, tools and methods that stop making a significant part of the population invisible. Fighting discrimination and revictimization requires recognizing and guaranteeing the rights of all victims. It should be remembered that only describing the characters that are related to biological sex can delay and/or confuse the identification process of trans people.

Hence, the AM registration form must include many questions related to gender identity to guarantee that the LGBTIQ+ community has the right to request a differentiated approach and a true gender perspective that allows validating the tool with variables that reflect this diversity. In the same way, a review of the methods and techniques that are currently used in anthropology and medicine is necessary, because today it is a mistake to approach the identification process without considering the implications that the social component has in the identity of a person. In this sense, identification manuals and protocols have to take a turn to implement and represent from a methodological perspective the value of body modifications or hormonal treatments for the identification of the trans population. Therefore, forensic science still has a challenge ahead if it wants to really work on identification from a gender perspective. For this reason, it is necessary that research be developed from the academy that aims to facilitate the identification of trans people. As well as constant updates to the forensic protocols that are used in the field of search, investigation, and identification, in addition to facilitating constant training for the different professionals who participate in these contexts.

References

- WHO (2018) Gender and Health.

- Vera Morales A (2020) Transfeminicides: Mexico Case 2019. Sexology and Society Magazine 26(1): 70-82.

- Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) (2015) Violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and intersex people in America. Washington DC Organization of American States.

- The Trans Murder Monitoring (TMM) (2019) TMM Update Trans Day Remembrance.

- Beltrán Gil I (2022) Is gender diversity present in the search? Where do the disappeared go.

- United Nations (2017) Minnesota Protocol on the Investigation of Potentially Unlawful Deaths (2016): Revised version of the United Nations manual on the effective prevention and investigation of extra-legal, arbitrary, or summary executions, United Nations.

- PGR (2015) Protocol for treatment and forensic identification. Mexico.

- Office of the Attorney General of the Republic (2015) General Agreement A/009/15 establishing the guidelines that public servants involved in chain of custody must observe.

- Chavarría Tenorio B (2023) Mothers of victims of femicide and disappearance reject public apology from Prosecutor Edomex.

- Cummings S (2003) Hormone replacement therapy and fracture risk: what is the evidence? Medwave 3(2).

- Fernández Morales D (2007) Indications for the use of oral hormone replacement therapy in menopausal women older than 50 years. Costa Rican Medical Act 49(1): 26-32.

- Martínez Morales G (2004) Hormone replacement therapy and cancer. Colombian J Obstet Gynecol 55(1): 48-69.

- Landa MC (2003) Role of hormone replacement therapy in the prevention and treatment of menopausal osteoporosis. Annals of the Health System of Navarra 26(Suppl 3): 99-105.

- Stowell JT, Garner HW, Herrmann S, Tilson K, Stanborough R (2020) Bone health of transgender adults: what the radiologist needs to know. Skeletal Radiol 49(10): 1525-1537.

- Abdala R, Nagelberg A, Brance ML (2020) Bone health in transgender people. Updat Osteol 16(3): 176-186.

- Calvar C, Cabrera N, Duran Y (2017) Cross-hormone treatment of transgender people and its complications. SAGI J 24(2).

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...