Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4595

Short Communication(ISSN: 2637-4595)

Six Forms of Sustainable Fashion Volume 2 - Issue 4

Iva Jestratijevic* and Nancy A Rudd

- Human Sciences, Fashion and Retail Program, College of Education and Human Ecology, The Ohio State University, USA

Received: August 08, 2018; Published: August 13, 2018

*Corresponding author:Iva Jestratijevic, Human Sciences, Fashion and Retail Program, College of Education and Human Ecology, The Ohio State University, USA

DOI: 10.32474/LTTFD.2018.02.000145

Short Communication

Sustainability conundrum

Since the early 2000s, rapid global decline of natural resources and ongoing climate change have challenged businesses to improve all procedures and strategies to sustain the environment, society, and success. Sustainability was recognized as a holistic solution for dramatic market shift, where outstanding performance requires the symbiosis of economic (profit), social (people), and environmental (planet) partnerships Connell & Kozar [1]. People, planet, and profit, the three pillars (or 3Ps,) of sustainable business, represent Triple Bottom Line (TBL) benchmark that is used to assess sustainable corporate performance Lampikoski [2], Elkington [3]. Apart from the sustainable business guidance, sustainability misconceptions are systematically produced by different industry players. Most commonly, sustainability is compartmentalized as an environmental issue. Even through the natural resources scarcity and ongoing climate change highly affect life of individuals, regions, and communities, sustainability is often disregarded as an equally important social problem.

Particularly across fashion media, environmental sustainability has often been misleadingly promoted. For example, in the 1990s fashion magazines, environmentally friendly fashion (or the socalled green chick), was described as “pure”, “natural (green)” and “recycled”, regardless of its production ethics and the material provenance Fletcher [4]. Even today, some fashion brands promote sustainable commitments mainly through pro-environmental improvements such as resource circularity, recycling, and repair, while their pro-social business activities such as workers’ rights, anti-discrimination, living wage, child labor, etc., especially in their supply chain, remain mostly unknown or are less advertised Ditty [5]. Similarly, some apparel products are labeled as eco, conscious or sustainable even when they obviously lack official certification or have ambiguous materials list and unclear information on product’s country of origin Strähle J [6]. This practice creates uncertainty on the consumers’ side, as they report that they are not sure what sustainability means, what social and/or environmental consequences fashion production and consumption entails, and why there is a high need for textile recycling Morgan & Birtwistle [7] Kagawa [8], Strähle & Hauk [9].

Sustainable fashion

To advance the knowledge related to triple bottom line sustainability in the textile and clothing industry, we aim to elaborate the core values of sustainable fashion philosophy and propose classification of six forms of sustainable fashion. Even though fashion business is very lucrative, production of clothing and textiles is one of the most polluting industrial processes that require a lot of water, energy, chemicals, and natural resources Cline EL [10]. Production strongly relies on human labor, as various processes cannot be fully automatized. Globally dispersed production chains highly affect life of millions of legal and illegal workers who are exploited, abused, and deprived of basic human rights Maryanov [11]. Although the growing social and environmental issues weaken realistic possibilities of fashion industry to become fully sustainable, there are things that might support change and secure gradual improvements. Perhaps the most common understanding of sustainability advancements is the one related to the business itself. Sustainable fashion is embedded in the entire business model and it determines how, where, and under what conditions products are made. It also determines how the products are packaged, labeled, and promoted while assuring that product declarations clearly instruct consumers how to maintain, repair or dispose goods they bought.

Sustainable fashion is intended to generate wellbeing, not only for companies and shareholders, but for all different stakeholders and people involved in or affected by the sourcing, production, use, reuse, and disposal of textiles Fletcher [4]. Opposed to fast fashion and disposable business mindset, sustainable fashion is well grounded in the principle of connectivity and shared values. Unlike ephemeral markers, sustainable fashion truly aims to reattach people to the clothing they wear. It reconnects consumers with different producers, starting from the person who stitched, dyed or labeled the product, to the person who put it in the retail shelves. Sustainable fashion is well grounded in conscientious aesthetics by which products are designed to last. In order to switch to sustainable future, a transformative business needs to shift from linearity reflected in take-make-dispose logic and accept circular mentality by which things are used-and re-used Niinimäki K [12]. Fashion circularity is inherent to Cradle to Cradle philosophy, which, as Ellen MacArthur Foundation proclaims, treats product disposal as entrance to the next product life cycle MacArthur [13]. Aligned with that philosophy, sustainable fashion aims to reduce waste, preserve already created products, and save natural resources.

Therefore, all newly created products must fit into one of two categories and be ether

a) biodegradable, i.e. naturally decomposable.

b) recyclable in either mechanical or chemical way Fletcher [4].

Aiming to extend life cycle of already existing whole products, sustainable fashion supports product re-use that may involve redistribution and resale. Sharing pre-owned clothes with others in need brings, apart from social significance, important environmental savings, as reselling clothes preserves resources otherwise needed for a new production. Instead of quantity, consumers are invited to shop for quality, as high quality products are durable and can be repaired. Sustainable luxury is inherent to the slow fashion cycle, where valuable, high quality goods are produced, worn, maintained and, if not needed, passed to others to use them for the same purpose. Sustainable fashion is compassionate as it sincerely aims to reduce negative environmental and social performance.

Six forms of sustainable fashion

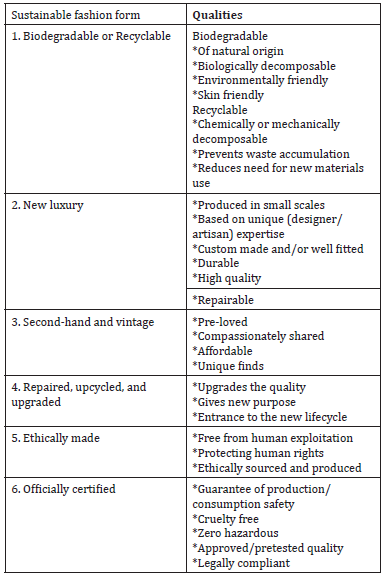

We acknowledge that sustainable fashion journey has only begun, and many paths of the sustainable improvement are created along the way. To contribute to those efforts, we provide a framework that might direct the sustainable fashion classification. We propose six forms of sustainable fashion (Table 1)

a) Biodegradable or recyclable products that can be naturally decomposed or technologically recycled.

b) New luxury products that are durable and repairable. Sustainable luxury brands that can be both locally (artisan work) and globally relevant (traditional luxury).

c) Second-hand and vintage products that are donated, redistributed, and resold for reuse purposes.

d) Repaired, upcycled and upgraded products that were previously discarded, but repurposed to gain new life (e.g. patchwork denim collections).

e) Ethically made products taking into consideration the workers’ rights in the entire supply chain - from raw material to the final stage of product suppliers.

f) Officially certified products labeled with approved trademark that guarantees product safety, quality, and production ethics (e.g. Fair Trade).

Ideally, all these available fashion forms should be used to enhance sustainable business performance, as implementing only one while disregarding others does not satisfy triple bottom sustainability requirements. As sustainability knowledge continually evolves through industry experience and application, we believe that more alternative solutions for circular fashion will eventually establish their ways.

References

- Connell KYH, Kozar JM (2017) Introduction to special issue on sustainability and the triple bottom line within the global clothing and textiles industry. Fashion and Textiles 4: 16.

- Lampikoski T, Westerlund M, Rajala R, Möller K (2014) Green innovation games: Value-creation strategies for corporate sustainability. California Management Review 57(1): 88-116.

- Elkington J (1998) Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st‐century business. Environmental Quality Management 8(1): 37-51.

- Fletcher K (2013) Sustainable fashion and textiles: design journeys. Routledge London, UK.

- Ditty S (2017) Fashion transparency index.

- Strähle J (2017) Green Fashion Retail. In Strähle, Jochen (Ed.) Green Fashion Retail. Springer Singapore p. 1-6.

- Morgan LR, Birtwistle G (2009) An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. International journal of consumer studies 33(2): 190-198.

- Kagawa F (2007) Dissonance in students’ perceptions of sustainable development and sustainability: Implications for curriculum change. International journal of sustainability in higher education 8(3): 317-338.

- Strähle J, Hauk K (2017) Impact on sustainability: production versus consumption. In Strähle, Jochen (Ed.) Green Fashion Retail Springer, Singapore p. 49-75.

- Cline EL (2012) Overdressed: The shockingly high cost of cheap fashion. Penguin

- Maryanov DC (2010) Sweatshop liability: Corporate codes of conduct and the governance of labor standards in the international supply chain. Lewis & Clark L Rev 14: 397.

- Niinimäki K (2011) From disposable to sustainable: the complex interplay between design and consumption of textiles and clothing. Aalto University, Finland.

- MacArthur E (2013) Towards a circular economy-Economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition. Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...