Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4595

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-4595)

Hijab in Fashion 1990-2020 Volume 4 - Issue 1

Umer Hameed1*, SaimaUmer2 and Usman Hameed2

- 1National Textile University, Pakistan

- 2Punjab University Lahore, Pakistan

Received:June 01, 2021 Published: June 11, 2021

*Corresponding author: Umer Hameed, National Textile University, Pakistan

DOI: 10.32474/LTTFD.2021.04.000180

Abstract

Surrounding the increasing debate around the Muslim veil, my research paper sought to investigate the hijab and how it is being used within the context of the Fashion industry. The paper is divided into five sections. There is the introduction section, which gives an overview of what will be covered in the paper. This is followed by focuses on the history of the hijab as well as its cultural aspect. Thereafter I review the major ways in which wearing hijab has changed in the era of social media coupled with a fast-changing fashion industry. Afterwards, I will focus on the ways in which veiled Muslim women are subjected to negative stereotyping and profiling. The Conclusion gives a recap of the major findings while recommending ways through which social justice and other approaches can be executed in order to overcome stereotypical behaviors meted against Muslims.

Keywords:Modest fashion; Abaya; Hijab; Islamic Clothing; evolution of fashion

Author’s Biography

I have worked within the Academia for over 12 Years as an educationalist n and administrator. I rendered my services as Assistant professor / Chairman Design Department, National Textile University Faisalabad for about six years. I completed many projects and associated with various tasks related to this position. n Education, I have completed my graduation in Textile Design from the National College of Arts, Lahore, Pakistan, and completed my MS/ MPhil in Textile & Clothing from GC University Faisalabad. I have enrolled in a Doctor of Education from the University of Liverpool UK.

Introduction

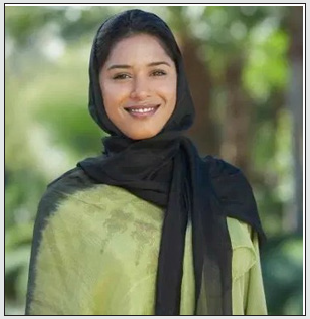

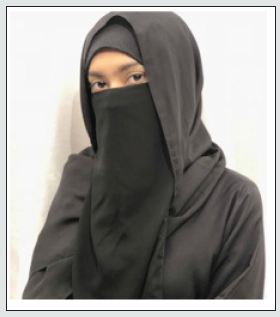

Clothing is an important component of human life in the sense that it requires people to cover and protect themselves as well as providing them a feeling of attractiveness while moving around with comfort. In this view, it follows that every individual needs to clothe him or herself and the garment of choice should be acceptable by their respective society members. Different societies have diverse modes and styles of clothing that they consider to be modest, and what they consider to be fashionable. For the purpose of this paper, the focus will be on the Muslim society and their mode of dressing with a key focus on the hijab, as explored within the context of fashion. In Islam, Prophet Mohammed, a great deal of importance is placed on the dress code within the Muslim community since any garment that deviates from the set acceptable norms, values and standards is considered to be indecent.7 It goes against the Islamic teachings and values for women to wear garments that expose whatever they have worn underneath; and in the same context, that Muslim women are encouraged to practice head covering as a way of concealing their “bosom.” As such, head covering has become synonymous with the Muslim woman; the type of dress gained further popularity among Muslims during the last quarter of the 20th century [1]. There are a number of different garments, other than the hijab, worn by Muslim women to conceal their bodies, including but not limited to: the niqab, chador, shayla, jilbab, shalwar kameez, dupatta, tudung and burqa. These garments come in different styles, colors, and materials, as will be seen in the illustrations to follow. These coverings come in different styles, colors, forms and denominations as encapsulated in different cultural frames based on the inherent ethnicity and religion of each culture which embraces them. For instance, there is the chador in Iran, the buibui in East Africa, the purdah in Pakistan, the abaya in Saudi Arabia, the burqa is seen in Afghanistan, and the kerudung in Malaysia. However, each of these headscarves are largely referred to as simply the hijab in Western countries [2]. As shown in Figure 1, a hijab is a veil worn by Muslim women in order to cover their head and neck while revealing their faces. A niqab is a garment used by Muslim women to cover their face while leaving the area around their eyes exposed. It is another common type of a head covering, more common in countries located in the Gulf region. It is usually worn with an accompanying loose robe, or a headscarf and the styles undoubtedly vary from one religion to the other as well as according to different geographic regions. For instance, some women wear a “half niqab” (Figure 2) versus a full niqab. There is the tudong (also spelled tudung) - a common headscarf worn by Muslim women in Southeast Asia, specifically Malaysia and Singapore, as well as in Turkey . There seems to be no apparent distinction between the hijab and tudong, as both are used for the covering of the hair, neck and ears while leaving the face exposed. But as evident from the image, this type of covering is fastened using a button or pin under the neck, while the hijab is usually secured on the side of the head.

Figure 2: A Luxury Black Elastic Half Niqab, 32 cm wide and 31 cm long, for sale online from The Muslimah Collection.

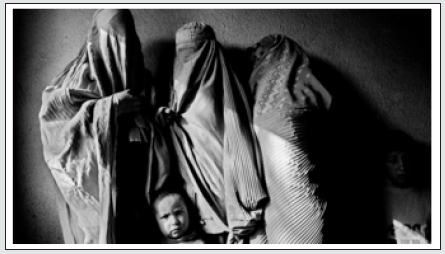

Another common type of hijab is the chador, a semicircle section of fabric draped over the head. Similar to the tudung, it covers the hair and ears while leaving the face open. As shown in Figure 3, the chador resembles a shawl by Western standards. It is mostly worn by Iranian Muslim women and contains no fasteners. Instead, the wearer will hold it under the neck using her hands. However, in some cases it may be worn with some pins or ties in order to keep it neat and steady. Black is the most common color worn in public, but Muslim women will wear it in different versions and colors while at home or when visiting the mosque. The most concealing garment of all the veils and head-coverings worn by Muslim women is the burka. It is normally a voluminous and long outer garment that covers the entire body normally leaving a “mesh screen or grille” on the eyes as shown in Figure 4. It is mostly worn in Central Asia but is used in countries such as Pakistan and Afghanistan, where it is considered to be a symbol of stature and respect within the Muslim community [3]. There is also the burkini (Figure 5) which is a modest swimsuit covering the entire body and the hair while leaving the face open. The idea behind this hijab style is to ensure that a swimmer is comfortable and the material light enough to swim in while concealing her body. As such, it is mainly meant to promote sporting activities while at the same time honoring Islamic values and ideals on modest clothing. As earlier mentioned, the focus of this paper will be on the hijab and its complex role in the world of fashion and society. This paper will evaluate the history of hijab, different perspectives of women wearing the hijab within the contemporary context, as well as issues of stereotyping and Muslim dress profiling in modern day.

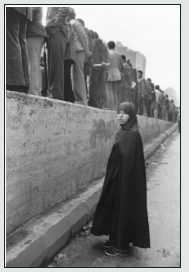

Figure 3: A chador-clad woman stands behind a line of men during a demonstration against the regime. Abbas. Tehran. December 1978.

Figure 5: A Muslim woman wearing a burkini at a swimming pool. Photograph. Photo via Kzenon / Shutterstock (Fair Use).

History of the hijab

From the outset, it is imperative to note that the wearing of scarves and veils among women started long ago even before the emergence of Islam as a religion. The foundation of Islam can be traced back to the period between c. 570–632 CE, where it was established by Prophet Mohammed in the Arabian Peninsula before spreading to the Middle East and many other countries. Islam has become one of the largest religious groups in the world and hijabs are largely synonymous with the Islamic religion, though it is important to underscore the fact that that meaning of Islamic attires does vary from one country and socio-cultural context to the other [4]. Rahman and Benjamin [5] discussed that There have been major changes that have taken place in regard to the assigned meaning of the hijab from one country to the other as explained in this section. According to experts Koo and Han [6], authors of To Veil or Not to Veil: Turkish and Iranian Hijab Policies and The Struggle for Recognition, Iran was a highly conservative country during the early 20th century whereby the orthodox men would verbally and physically abuse those women that did not wear hijabs. However, and just like in other Muslim countries, there were conflicting opinions regarding the hijab during this time period, with one side supporting its use while the other opposed its prescribed wearing. For instance, there was the Reza Shah Modernization policy of 1928 in Iran, which was against the continued wearing of tribal and ethnic clothing, including the hijab. Rezah Shah (r. 1941- 1979) introduced many positive reforms, reorganizing the nation’s army, government administration, and lifting its financial standing. He wanted to transform Iran to a modern and industrialized nation both socially and culturally. When visiting Turkey in 1934, where the use of hijab had been largely abandoned, the Shah felt that the hijab was one of the greatest obstacles for Iran to overcome in order to achieve modernization and he therefore passed a law two years later in which the wearing of the hijab was prohibited in some designated places such as the government offices, banks, and educational centers. The ban would later extend to other public as well as private places, and by the year 1936, the country had become a pioneer state to prohibit the wearing of hijab [7].

Moving forward, Rezah Shah continued to advocate for the abolition of the hijab as an awakening call for women and a national path towards progress. However, there were some communities that were opposed to the policy. Ironically, and despite this move being viewed as a women’s liberation process, women were still not allowed to take part in political circles. In fact, and according to Koo and Han, the policy was not aimed at empowering women but rather to further strip away women’s rights. It would later be seen as a move by the government to wrongly utilize its control over the female body [6]. Fedorak [7] deliberated that However, the wearing of the hijab by Muslim women was re-introduced later in 1941 following the abdication of Reza Shah. The Shah had allowed women to decide their own use of the hijab and since the veil was no longer being legally enforced, some women and especially those from the conservative families went back to wearing their chadors and other coverings. On the other hand, women, especially those from the elite classes, disregarded the hijabs in favor of western style clothing. The clergy, alongside some members of the public, became critical and resentful about the continued disregard of the traditional value systems by the Muslim elite class (Figure 6). This would lead to another revolution; and by 1979, a new policy advocating for the continued wearing of the hijab was introduced. During this time the hijab was perceived as a symbol of democracy and opposition against the continued dominance of Iran by western nations. During this revolution in 1978-79, led by Ayatollah Khomeini, wearing the hijab became a symbol of resistance and protest against the monarchy of Mohammad Reza Shah.

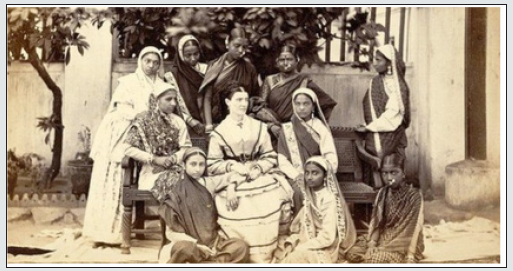

Figure 6: Indian Women in traditional coverings during the Victorian Era. 19th Century. Photograph. Flora Annie Steel and Grace Gardiner: The Complete Indian Housekeeper and Cook: Oxford University Press, first published 1888.

Post-revolution: The Iranian government implemented a new code pioneered by Khomeini which made the wearing of hijab among Muslim women compulsories. To this day, most Iranian women are not overly resistant to the wearing of hijab, but understandably rather torn over their lack of control over its use [6]. Masih [8] discussed that Many Iranian women who oppose the hijab policy have been arrested for their disregard of the Iranian laws. Based on an article published by the Human Rights Watch, three women from Iran were sentenced to forty-eight lashings and thirty-three years in prison as recently as 2018 for protesting against the laws that make wearing of the hijab compulsory [9]. According to Qazi [10], In India, issues of dress have also been a subject of debate. Unlike in other countries such as Pakistan and Iran, where wearing of the veil is compulsory, there are no written codes about what Muslim women in India should wear. India as a nation is comprised of different traditions, primarily those belonging to the Hindu and Muslim religions. During the 15th century, Indian women would wear different types of outfits and all through the 16th and 17th century, during the Mughal’s regime, there were no written codes or policies on what women were expected to wear (Figure 7). However, and just like in other jurisdictions, there are those people who are in support of the hijab in India and those who are opposed to it. In some extreme instances, indecent wearing has been associated with rape and other violent acts. However, those opposed to the Muslim veil, including the hijab, argue that these violent acts against women are not influenced by dress code but rather are a result of how some men react to the larger idea of women’s autonomy.

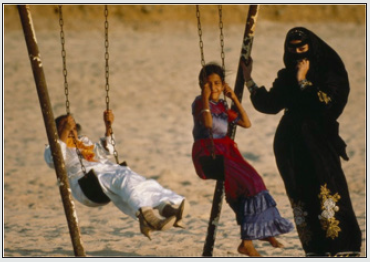

Figure 7: Veiled woman with daughters, Saudi Arabia (February 11, 2013) Jodi Cobb: National Geographic Magazine.

As stated in the preceding section, the veil has been used by Muslim women to maintain their modesty, promote their security and safety while protecting their privacy from any unrelated males. Although some of the anti-hijab proponents have argued that the veil is used to maintain male control and dominance, its supporters, mainly clergy members, insist that the hijab, among other veils, are partly used for the advancement of feminist ideals as well as a control measure for women over their own bodies. By wearing the hijab, it is thought by some that Muslim women are able to hide their bodies, promote positive ideals, and avert unnecessary attention from their male counterparts who may be seduced by women who wear skimpy clothes that leave their bodies exposed (Figure 8). This makes for some extreme consequences. For instance, and within the Pakistani context, it is required that women should not take part in any sports that are open to public viewing. Additionally, women in Pakistan should remain within their homestead and only walk out when they are completely covered and unrecognizable. This is meant to promote chastity; any exposure of women’s bodies is considered a dishonor to their families. In this regard, wearing the hijab, or the purdah in Pakistan, is treated with the utmost importance [11].

Figure 8: Installation view of “Contemporary Muslim Fashion”, Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian National Museum of Design, New York; Saba Ali, stylist for the exhibition.

Hijab as understood within a cultural context

Within the cultural context, the hijab has extensively been used as an important identifier of Muslim women. These sentiments are supported in a study that was undertaken by Rahman and Benjamin in 2016. “Exploring The Meanings of Hijab Through Online Comments in Canada” cites a study that described different Islamic attires, primarily the hijab, burqa and niqab, being perceived as important visual markers

for Muslim women. Besides serving as an identity marker, body and head coverings have also been used as repositories for religious identity [5]. According to Kamal [1], author of “Conditions of Wearing Hijab and Other Forms of Dress: A Comparative Study” the hijab is used by Muslim women as a sign of modernity. Also, it serves an important role for behavioral checks and controls, preserves the concept of marital relationship protection, provides freedom for women, and helps avert issues of sexual objectification for the Muslim women. Wearing the hijab is often a cultural, rather than a religious, construct. It has been made clear that it is not a strict, single interpretation, and many Muslim women do not wear special coverings at all. A photo captured by National Geographic photographer, Jodi Cobb, shows the mother of a Saudi family (Figure 8) who wears a full abaya, while her daughters play at the playground unveiled [12].

The Hijab today, fast fashion and social media

Fashion continues to be used as an important medium by different people to express their identities and behaviors. According to most research (i.e., Muhammad Jan, et al. [13] on the subject of fashion and consumerism on social media platforms, it maintains that people will mostly adopt trends with the aim of raising their self-esteem as well as becoming stylish. Jan and Kalthom [13] discussed that However, and as earlier indicated, the prevailing social, religious and cultural constructs will determine the suitability of a certain fashion and style. This means that some fashion and styles will be considered indecent and unacceptable within different societies. For instance, and within the Islamic traditions, wearing the hijab has been associated with different social, political, economic, and religious aspects as explained in the preceding sections. The debates surrounding the hijab and its significance as a fashion statement have been intensified by the emergence and continued use of social media. Hijabs come in different forms, styles, colors, and materials depending on the cultural and social affiliation of the wearer. As in other religions, a substantial number of Muslim women like to appear trendy, fashionable, and stylish in their hijabs. It is in this context that some Muslim women have taken active participation across different social media networks such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, among others. It is a common trend to see a wide range of hashtags that involve the integration of hijabs within fashion-related imagery and narratives; these hashtags are mainly found in social media networks such as Instagram and Facebook as well as on different online blogs. Through such activity, different young Muslims from across the world are able to showcase their “cool” and fashionable hijabs to their peers. Most of these veils are integrated with the latest fashions and styles as a way of promoting modernity. This has further been supported by different online magazines and websites that teach Muslim women how to pair their hijabs with different T-shirts, pants, as well as purses [14].

Figure 9: Yasmin Sobeih (b. 1990, United Kingdom) for UNDER-RÂPT (est. 2017, United Kingdom); Ensemble (raincoat, T-shirt, shorts, hooded top, and sport tights); 2018; Printed MicroModal®, Tencel™; Courtesy of UNDER-RÂPT.

Saba Ali (Figure 9) was the lead stylist for Contemporary Muslim Fashion, an exhibition currently on view at the Cooper- Hewitt Smithsonian National Museum of Design in New York that examines the ascendancy of the global modest fashion industry. Ali feels modest fashion would not have the platform it does without the Internet, which has given birth to globalization and the democratization of fashion as a whole. Ali’s generation has seen this shift and she “enjoys seeing what everyone is doing with the visibility they have been given. It’s inspiring and welds us all together in a powerful way” [15]. The sentiments are shared by Nistor [2], who underscores the fact that social media and other fashion blogs have provided, and continue to provide, opportunities for Muslim fashion enthusiasts to share important information about their clothing and style. The author notes that the ability to share modern fashionable hijabs creates a strong motivational base of support on which young Muslim women can influence their peers to embrace the concept of wearing the hijab in order to promote their sense of independence. In fact, through these recent trends as propelled by social media, there has been the emergence of different hijabfashion subcultures, one for example being Hijabistas – detailed on page 20 of this paper. Developments such as the continued use of social media have considerably helped diffuse misconceptions about why women wear the hijab. Research undertaken by Siti and Harun in their 2014 article, “Factors Influencing Fashion Consciousness’. In Hijab Fashion Consumption Among Hijabistas” states that all Muslim women have continued to gain increased empowerment during this digital era, and they continue to actively participate in all spheres of life both within the public and private sectors. Women are increasingly becoming doctors, lawyers, as well as government officials in many of the countries mentioned in the previous chapter that have had a history of compulsory laws forcing women to cover themselves. Some of these new developments have occurred due to the increased use of digital platforms, where women can educate and influence each other in a positive manner [16].

Within the Islamic context, an increasing number of Muslimmajority countries continue to embrace the concept of “Muslim Cosmopolitanism”, whereby Muslim women are given the latitude to express their identity and individuality through emerging fashion trends. In other words, and despite conforming to the socio-cultural and religious requirement of covering their bodies, Muslim women now showcase their hijab trends, characterized by different colors as well as styles coupled with various accessories. The content shared online has also encouraged hijabi fashion designers to innovate. This innovation has been made possible since social media has created a platform where more women feel empowered and can communicate shared experiences. These waves of information are utilized by many fashion designers and major name brand companies to inform their decisions in coming up with products that appeal to Muslim customer tastes and preferences [17]. For instance, Nike was the first company to introduce a sports hijab in 2017. This is a clear indication that the invention of social media is helping change the conventional beliefs and attitudes that people have toward the wearing of the hijab. People continue to embrace the concept of fashion and different ways through which the veil can be used outside the religious realms. Muslim fashion supermodels have also been enthusiastic to advertise different fashions of the hijab and have been instrumental in the way the hijab has been acknowledged and accepted by both ready-to-wear and fast- fashion brands. For instance, Figure 10 shows a Muslim supermodel, Halima Aden, featured in a hijab Sports swimsuit [18]. The hijab fashion as influenced by increased use of social media can also be understood by looking at the rise of Hijabistas – defined as a Muslim woman or girl who dresses stylishly while conforming to the Islamic modesty code. This influential class of Muslim women dress in fashionable clothing while still managing to ascribe to and keep a strong orientation towards the Islamic religious prescriptions of maintaining decency, which includes the wearing of veils such as the hijab, niqab, and burka [19]. Through the use of social media, Hijabistas have largely influenced how Muslim women veil. Some of the most influential bloggers within the Hijabista circles include, among others; Habiba da Silva, Heba Jalloul, Leena Asad, Mariah Idrissi, Omaya Zein, Dian Pelangi, Nura Afia, Yasemin Kanar, Amena Khan, Eileen Lahi, and Dalal Aldoud. “Modest fashion appears to be most affiliated with Muslim women but women of all faiths and backgrounds also practice the concept of covering up. For some women, it is empowering to choose to cover their bodies rather than experience the pressures of society for women to look a certain way,” Mariah Idrissi tells Grazia Middle East.

Figure 10: Halima Aden is the first model to wear a hijab and burkini for Sports Illustrated Swimsuit. Photograph. 2019.

Social media has been used as an important tool that influences the phenomenon of imitation. It has served an important role in the adoption of the bottom-up diffusion of fashion. Through the continued use of social media, people can now post images of wearing different types of hijab. This presentation of high- fashion display plays a significant role in the incorporation of a veil that is highly appealing to the Muslim population while at the same time taking a stand against the prevailing negative profiling and stigmatization of the Muslim woman [20]. We have seen hijabs that come in different styles, colors, and fashions. They may be referred to in different terms depending on the prevailing cultures and ethnicities as well as the country of origin for the wearers. These trends have been key in the fast- fashion industry, considering the presentation of the hijabs that differ in terms of color, fastening, seasonal use, style, as well as overall structure.

Negative profiling and stereotyping of the veiled Muslim woman

The meaning and extent of Islamic attire differs from one person to the other and from one socio-cultural context to the next. This is the primary basis behind the continued debate surrounding the wearing of hijab amongst Muslim women. From a non- Muslim point of view, hijabs and other types of veils have largely been associated with religious ties, solidarity, as well as resistance. Further, they are considered by some to symbolize extreme Islamism, to be a kind of symbol of enmity, a sign of male oppression, and lack of allegiance to the cultures of the host countries. However, among those Muslim women who wear different types of veils such sentiments are in all likelihood not the case. As observed by Rahman and Benjamin in “Exploring the Meanings of Hijab Through Online Comments in Canada”, however, some of these misconceptions and misinterpretations have been the basis for which Muslim women continue to face sometimes extreme cases of discrimination and negative stereotyping across the world. This has come to be termed as “Islamophobia” wherein the veil is seen as the metonymic differentiating factor between the “global population and them”, in this case “them” referring to Muslims. Based on existing literature, religious garments, primarily those worn by the Muslim women, have culminated into different misunderstandings that have, in some cases, resulted in adversarial racism against those people who profess the Islamic faith [5]. Koura [21] discussed that in some extreme cases, this negative profiling of Muslims has resulted in violence. One study carried out in Great Britain determined that intense bullying was taking place in secondary schools and was associated with the type of accessories and clothing worn by young Muslim school children. Similar issues have taken place in the United States, following the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001. Post-September 11, 2001, many Americans began to identity the Islamic veil as the symbol for the enemy; an image further fueled by some news and media outlets. Although previously the hijab alongside other Islamic garments was associated with religion, such dress was no longer seen, by some, as the marker of obedience to God. Instead, those wearing the hijab soon were associated and identified as equal to those waging terrorist war against America. Veiled Muslim women even became “soft targets” and bore the brunt as a consequence of negative stereotyping by other social groupings in America. Even in the post-September 11th era the United States continues to see an uptick in allegations of hate-related incidents following some of the tragic events that have taken place. Vanita Gupta, who leads the New York Justice Department’s civil rights division comments, “We see criminal threats against mosques; harassment in schools; and reports of violence targeting Muslim- Americans, Sikhs, people of Arab or South-Asian descent and people perceived to be members of these groups,”

To this day, veiled Muslim women continue to receive both harassment and pitying; they are in some cases subject to adverse violence each and every day. Some of the epithets that have been used include, “You are not American”, and “Go home”. This issue of negative stereotyping against Muslims was further exacerbated in 2017 when President Donald J. Trump called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” [22]. Even today, the hijab is perceived as being “un-American”, implying that the majority culture in America cannot co-exist with Islamic traditions and values. Even though many of the Muslim women who embrace and wear the hijab are in fact native born, they are considered and perceived as being “foreign”. They are thus regarded as “Others”, which eventually exposes their vulnerability to verbal attacks and at times even physical assault [21]. The above sentiments are supported by women I have spoken to over the course of my research that have relayed they feel Muslims in the US are subjected to adverse violation of civil liberties. Journalist Ashley Moore acknowledges that issues of social discrimination and physical abuse against Muslims are not uncommon in Western countries. Muslims face regular abuse cases such face to face, telephone, and internet threats. As a community they have been subject to major violence, including but not limited to vandalism, physical harassment, shootings, as well as bombings of their homes and places of worship.

The primary basis for such abuse is partially linked to the negative stereotyping of the Islam religion, whereby people from the mainstream cultures want to “drive away” the Muslims from the United States. As has been noted above, wearing the hijab signals a proven marker of this profiling (Ashley Moore). In other scenarios, Muslim women wearing the veils are portrayed as objects of male dominance. As women, they are perceived as being unable to free themselves from male control. A case scenario can be cited in a study that was carried out by Latiff and Fatin [14], which explores how veiled Muslim women are profiled negatively by the western media. The authors declare that women in headscarves of any type are portrayed as veiled victims who are unable to fight for their space and freedom in their mother countries, therefore fleeing to foreign lands as a way of trying to find some form of liberation. It follows that not all Muslim women wear the hijab and other types of veils out of their own volition but that some are forced by the prevailing social and cultural ties that put the patriarchy above all else. It is on this basis that many non-Muslims in countries such as the United States perceive the wearing of the hijab as a form of male oppression and chauvinism, thereby portraying such women as being weaker and unable to rise above such issues of male domination [5].

One primary reason that veiled women have been deemed a threat, is that when some of them choose traditional Islamic dress, they are concealing most of their body and also hide their identity. In a highly dynamic and changing world, terrorism has become a major global problem, and the identity of every person becomes paramount to the security of each nation but for followers of Islam who signal their identity through the way they dress, their clothing can sometimes feel like a red flag [14]. Luongo [23] discussed that unfortunately, some Islamic cultures prohibit women from exposing any parts of their bodies except to their husbands and close family. This carries with it a negative perception and personal discomfort when veiled women are confronted at security checks and then must claim that their traditions, values, and norms prohibit them from undergoing such security scrutiny. It also may convey a negative image to security personnel who will view these women as potential security risks. Simply put, the negative connotation of “Islamophobia” or more particularly “dress profiling” has largely taken away the freedom and anonymity of veiled Muslim women. It is imperative to underscore the fact that Islam is the 2nd largest religion globally, and that the Muslim population has been one of the fastest growing in the United States with projections showing that it will double by the year 2030.In the midst of these dynamics, the existing literature shows that the Muslim American population continues to report the largest number of discrimination-related claims closely associated with issues of religious extremism. Further, most of the Muslim women wearing the hijab and other forms of Islamic garments have been subjected to covert stereotyping such as prolonged eye contact and failure to be served in the different government offices across the United States. The negative perception and stereotyping has also been experienced within the job market, whereby some Muslim women who wear the hijab have lost potential job opportunities on the mere basis of them being Muslim. Studies have found extreme cases of intolerance and refusal to accommodate women in the workplace and especially those associated with the Islamic faith [24].

The Supreme Court of the United States ruled in the favor of Elauf and the EEOC in its June 1, 2015, decision, declaring that an employer may not refuse to hire an applicant if the employer was motivated by avoiding the need to accommodate a religious practice. Such behavior violates the prohibition on religious discrimination contained in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 [25]. This form of discrimination in the workplace does not only take place in Western countries but is also apparent in other regions of the world. Another example can be cited from an article published in India. In this case, a female social worker in India was denied a job opportunity primarily because the recruiting agent felt that the hijab made the social worker look more like a “Muslim Lady” [10]. In regard to the code of dress, some non-Muslims have argued that veils, including the hijab, are not stylish and are a limitation for the Muslim women to perform certain jobs or even participate in certain sports. The negative aspect of this misconception, that veiled women are physically constrained by wearing the hijab when participating in sports, deny them the opportunity to appear decent, according to their faith, and be fashionable or to express themselves. Traditionally, most hijabs and other types of veils were black in color but as established from the preceding sections, this trend has changed. Currently, Muslim women wear hijabs of different styles, colors, and materials by contrast to the past when veiling was the dictate of the males. Women now have the freedom to choose types of hijab and a combination of accessories to pair with it. As evident from the preceding sections, there are several hijabs that are modest according to Islamic standards and which align with the latest fashions. The ability of Muslims to participate in different types of sporting activities further demonstrates a new era, where Muslim women have risen above the traditional social construct of male dominance. This shows that the issue of females being subjects of domination within the Islamic religion is just a misconception, a stereotype, and not the reality. In other words, and as opposed to skewed belief that Muslim women have no say in what to wear, they have gradually been achieving some independence in regard to their personal freedoms, which can be seen in what they choose to wear [26-29].

Conclusion

Based on the current analysis, different cultures subscribe to specific norms, values, and beliefs. Such norms and values dictate the societal expectations on how its members are expected to conduct themselves. The way in which people are expected to dress, and whether the type of garment may be considered decent or offensive, is based on the prevailing social constructs. For the purpose of this paper, the focus was on the hijab, which is understood by many as synonymous with Muslim womanhood. The paper has shown how different people assign different meanings to hijab and other types of garments worn by Muslim women. The act of wearing the hijab has multiple meanings and is a complex fashion statement in addition to being both religiously and socially significant. For many Muslims, garments such as hijabs, niqabs, and burkas are important as they believe that they help promote societal decency; they cover women’s bodies to prevent unnecessary male attention thus promoting safety and security. While to some (non-Muslims and Muslims alike) such garments exemplify the continued male dominance within the Islamic religion. They may go so far as to consider such dress as a threat to humanity. Further on the negative side, the hijab has been associated with terrorism, and in some cases, this may be strongly entrenched within the minds of some Americans. As I have established in this paper, such prejudice comes from generalization and overall misconception and needs importantly to be brought into the realm of social justice. Hijab-wearing women have been stereotyped in the workplace; they have had crimes committed against them, in extreme cases their homes have been bombed, and family members shot, while being exposed to many other negative experiences. As pointed out in this paper, the Muslim population continues to increase, and while it is a great challenge it is imperative for the Muslim and Christian culture to co-exist, in the United States and elsewhere. Considering recent political dynamics, it becomes crucial for policy makers and all relevant stakeholders to foster social justice and leadership. Job opportunities should be on the basis of merit, and resource distribution should be equal regardless of religious affiliation or the way one dresses. As has been pointed out in this research, Islamic clothing has undergone major changes in the recent past, with new fashions, colors, styles, and materials that characterize contemporary hijabs, niqabs, and burqas, among other Islamic veils. In the same way, it is a positive development that prominent fashion designers now integrate Islamic clothing within the American context. This will help elevate the hijab in a positive way not only within the fashion industry, but throughout society at large. Creating awareness about the hijab and Islamic traditions while engaging Muslims in the national policy making processes will help all of us to better understand that different norms, values, and practices add to a vibrant world of fashion history.

References

- Kamal Anila (2016) Conditions of Wearing Hijab and Other Forms of Dress: A Comparative Study. Pakistan Journal of Women Studies 23(2): 91-102.

- Nistor Laura (2017) Hijab(Istas)-As Fashion Phenomenon. A Review. Social Analysis 7: 59–67.

- Jaffery Rabiya (2018) What is the Difference Between the Hijab, Niqab and Burka? Culture Trip.

- (2020) Brief History of The Veil in Islam. Facing History and Ourselves.

- Rahman Osmud, Benjamin Fung (2016) Exploring the Meanings of Hijab Through Online Comments in Canada. Journal Of Intercultural Communication Research 45(3): 214-232.

- Koo Gi, Ha Han (2018) To Veil or Not to Veil: Turkish and Iranian Hijabpolicies and The Struggle for Recognition. Asian Journal of Women's Studies 24(1): 47-70.

- Fedorak Shirley A (2013) Global Issues: A Cross-Cultural Perspective, University of Toronto Press, USA.

- Alinejad Masih (2018) The Wind in My Hair: My Fight for Freedom in Modern Iran. Little Brown and Company, New York, USA.

- Begum Rothna (2019) Iranian Women Rebel Against Dress Code. Human Rights Watch.

- Qazi Shereena (2017) Muslim Woman in India Denied Job for Wearing Hijab.

- Penne Elisha P (2013) The Hijab as Moral Space in Northern Nigeria. In African Dress: Fashion, Agency, Performance, edited by Karen Tranberg Hanson Bloomsbury Academic, New York, USA p. 62-80.

- OConnor, Sean P (2013) Hijab: Veiled in Controversy. National Geographic.

- Jan Muhammad, Kalthom Abdullah (2015) Fashion: Malaysian Muslim Women Perspective. European Scientific Journal pp. 438-454.

- Latiff, Zulkifli, Fatin Alam (2013) The Roles of Media in Influencing Women Wearing Hijab: An Analysis. Journal of Image and Graphics 1(1): 50-54.

- Holden, Hannah Maureen (2020) Q&A with Saba Ali, Stylist for Contemporary Muslim Fashions.

- Hassan Siti, Harmimi Harun ((2014)) Factors Influencing Fashion Consciousness in Hijab Fashion Consumption Among Hijabistas. Journal Of Islamic Marketing 7(4): 476-494.

- Shirazi Faegheh (2004) How the Hijab Has Grown into A Fashion Industry. The Conversation.

- Lodi Hafsa (2018) Over-Sized and N Trend: New Modest Styles from Under-Rapt. The National.

- Dixon Emily (2019) Halima Aden Becomes First Model to Wear Hijab and Burkini in Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue. CNN.

- McBride Aoibhinh (2020) Mariah Idrissi: I Don’t Feel Anything is Worth Compromising My Beliefs and Morality. Grazia Middle East.

- Koura Fatima (2018) Navigating Islam: The Hijab and The American Workplace. Societies 8(125): 1-9.

- Taylor Jessica (2015) Trump Calls for Total and Complete Shutdown of Muslims Entering US.

- Luongo, Michael T (2016) Traveling While Muslim Complicates Things. The New York Times, USA.

- Reeves Terrie, Arlise McKinney, Laila Azam (2012) Muslim Women’s Workplace Experiences: Implications for Strategic Diversity Initiatives. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 32(1): 49-67.

- Liptak Adam (2015) Muslim Woman Denied Job Over Head Scarf Wins in Supreme Court. The New York Times, USA.

- Eicher Joanne B, Sandra Lee Evenson, Hazel A Lutz (2008) The Visible Self: Global Perspectives on Dress, Culture and Society, Third Edition Fairchild Publications, New York, USA.

- Alleyne Allyssia (2016) Dolce & Gabbana Debuts Line of Hijabs and Abayas. CNN. Bashar Imani Muslim Women Break Down the Myths Around Hair and Hijab.

- Ibrahim Celine (2016) Wearing the Headscarf Is a Matter of Feminism, Aesthetics and Solidarity for Me. The New York Times, USA.

- Moore Ashley (2014) American Muslim Minorities: The New Human Rights Struggle. Human Rights & Human Welfare p. 91-99.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...