Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4595

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-4595)

Navigating Cultural Appropriation in Costume Design: Context Challenges and Responsible Approaches Volume 5 - Issue 5

Rashid Haroon1*, Tanjibul Hasan Sajib1 and Engr Eanamul Haque Nizam2

- 1Department of Drama & Dramatics, Jahangirnagar University (JU),Bangladesh

- 1Department of Fashion Design & Technology, BGMEA University of Fashion and Technology (BUFT), Bangladesh

- 2Department of Textile Engineering, Southeast University, Bangladesh

Received:July 17, 2023 Published: August 03, 2023

*Corresponding author: Rashid Haroon, Department of Drama & Dramatics, Jahangirnagar University (JU), Bangladesh

DOI: 10.32474/LTTFD.2023.05.000225

Abstract

This exploration investigates the complicated issue of cultural appropriation inside the field of costume design, zeroing in on its true capacity for mischief, misrepresentation, and propagation of generalizations. It digs into the authentic setting, power elements, style’s relationship with Orientalism, and the requirement for decolonization in costume design. The review underlines the significance of grasping setting, aim, and capable design rehearses to advance cultural appropriation and keep away from appropriation. By looking at different viewpoints and contextual analyses, the exploration plans to add to the ongoing discourse encompassing cultural appropriation in costume design and supporter for an additional comprehensive and culturally delicate future.

Keywords: Cultural appropriation; Costume design; Historical context; power dynamics; Orientalism; decolonization

Introduction

Costume design assumes a critical part in cultural representation, enveloping the creation and choice of pieces of clothing, extras, and generally visual feel that convey explicit implications and characters [1] Bird, 2006). From dramatic exhibitions and film creations to cultural celebrations and style shows, costume design has the ability to summon feelings, transport crowds to various time spans or areas, and convey the substance of characters or cultural stories. Nonetheless, inside the domain of “costume design”, the idea of “cultural appropriation” has acquired expanding consideration and examination. Cultural allocation alludes to the reception, getting, or impersonation of components from a specific culture by people or gatherings from an alternate cultural foundation [1]. It includes the utilization of cultural images, customs, or styles without appropriately figuring out, regarding, or affirmation of their importance to the starting society.

The significance of “cultural appropriation” to costume design lies in the potential for damage, misrepresentation, and propagation of generalizations. At the point when costume designers draw motivation from various societies, they should explore a perplexing scene of verifiable setting, power elements, and moral contemplations. Without cautious idea and cultural responsiveness, the line among appreciation and allocation can undoubtedly be obscured, bringing about destructive results and supporting cultural imbalances. We expect to give an extensive comprehension of the intricacies encompassing “cultural appropriation” in “costume design”, revealing insight into verifiable, social, and moral components of the issue. Through this study, we desire to encourage decisive reasoning, advance aware commitment, and add to the continuous discourse encompassing “cultural appropriation” in costume design. By investigating the difficulties, inspecting the effect, and recommending dependable methodologies, we can pursue a more comprehensive and culturally touchy future for costume design, where various customs are praised and addressed with trustworthiness and regard. The objectives of this study have given below in shortly:

a) To examine the historical context of cultural appropriation in costume design and understand its implications in terms of misrepresentation, perpetuation of stereotypes, and the erasure of marginalized cultures.

b) To analyze the power dynamics involved in cultural appropriation within the field of costume design, highlighting the role of designers in responsibly representing and honoring diverse cultures.

c) To propose ethical and responsible approaches to costume design that promote cultural appreciation, collaboration with communities, and the avoidance of cultural appropriation, in order to contribute to a more inclusive and culturally sensitive future for the field.

Historical Context: Understanding Appropriation in Costume Design

The subject of cultural appropriation in costume design is phenomenal, with a long and challenging history. Deloria [1] gives a significant verifiable outline of the manners by which Local American symbolism has been appropriated in American culture. Deloria contends that this allocation has frequently been utilized to sustain generalizations and confusions about Local Americans, and that it has added to the underestimation of Local societies. Eicher and Sumberg investigate the job of attire in the development of personality, remembering the ways for which cultural appointment can be utilized to make or build up generalizations. Eicher and Sumberg contend that cultural appointment can be a hurtful practice when it is utilized to take advantage of or distort different societies, yet that it can likewise be a positive power when advancing comprehension and enthusiasm for various cultures is utilized. Stewart-Haraway gives an exhaustive outline of the idea of cultural allocation, from its beginnings to its ongoing signs. Stewart-Haraway contends that cultural allotment is a complicated and challenged peculiarity, and that there is no single definition that can catch its full scope of implications and suggestions. These three books offer significant bits of knowledge into the perplexing and challenged subject of cultural assignment in costume design. By looking at the verifiable setting and taking into account the points of view of various researchers, we can acquire a more profound comprehension of the manners by which costume design can be utilized to sustain generalizations, distort societies, or advance cultural appreciation.

Examination of power dynamics

A significant part of cultural assignment in costume design is the assessment of Examination of power dynamics and the potential for misrepresentation. S. Elizabeth Bird’s work, Dressing in Quills: The Development of the Indian in American Mainstream society, offers important bits of knowledge into the power elements associated with the formation of Local American symbolism in mainstream society. Bird’s investigation of the development of Local American symbolism uncovers how costume design plays had an impact in sustaining power uneven characters and supporting generalizations. By analyzing the verifiable setting of Local American representation, Bird features how costume design has been complicit in the eradication of the intricacies and variety of Local American societies. For instance, Bird takes note of that Local American hats are much of the time utilized in mainstream society as a method for connoting “ferocity” or “viciousness.” This depiction is off base and destructive, as it sustains the generalization that Local Americans are rough and ignoble.

Bird’s examination prompts us to basically assess how costume design can unintentionally add to the misrepresentation of underestimated societies. At the point when designers get cultural components without legitimate comprehension or discussion with the starting networks, they risk sustaining destructive generalizations and further minimizing these societies. For instance, in the 2012 film The Solitary Officer, Johnny Depp assumed the part of Tonto, a Local American ally to the title character. Depp’s depiction of Tonto was condemned by numerous Local American gatherings, who contended that it was a bigot and off base generalization. By taking into account the bits of knowledge from Bird’s work, we can more readily comprehend the power elements at play in costume design and the obligation that designers have in depicting societies precisely and consciously.

Fashion, Orientalism, and Cultural Appropriation

The connection between fashion, Orientalism, and cultural appropriation is a mind boggling and critical point in costume design. The book Fashion and Orientalism: Dress, Textiles, and Culture from the 17th to the 21st Century,” edited by Adam Geczy and Vicki Karaminas, offers important bits of knowledge into the appropriation of Eastern societies in Western style (Geczy and Karaminas, 2018). By checking on this book, we can investigate the manners by which costume design has generally acquired components from Eastern societies, frequently without a profound comprehension of their cultural importance. The reception of such components, like conventional articles of clothing, materials, and themes, without any relevant connection to anything or regard, can propagate generalizations and build up power uneven characters among Western and Eastern societies (Geczy and Karaminas, 2018).

appropriation of Eastern societies in Western design brings up significant issues about the cultural ramifications and potential damage brought about by appropriating components without grasping their importance. It is critical to recognize the accounts, customs, and implications behind the cultural components utilized in costume design and to move toward their fuse with awareness and regard. By basically breaking down the experiences introduced in “Fashion and Orientalism,” we can acquire a superior comprehension of how costume design can unexpectedly add to the eradication of Eastern societies, support generalizations, and sustain cultural disparities. This examination features the significance of cultural skill, joint effort, and moral design rehearses in the domain of costume design to guarantee that cultural components are consciously utilized, celebrated, and comprehended.

Bird’s examination prompts us to basically assess how costume design can coincidentally add to the misrepresentation of minimized societies. At the point when designers acquire cultural components without legitimate comprehension or conference with the beginning networks, they risk sustaining hurtful generalizations and further minimizing these societies. In the 2009 film Avatar, the Na’vi are a fictional tribe of blue-skinned humanoids who live on the planet Pandora. The Na’vi are often depicted wearing traditional clothing made from animal skins and feathers. However, some critics have argued that this portrayal of the Na’vi is inaccurate and appropriative, as it does not reflect the diversity of Native American cultures.

For example, the Na’vi are often shown wearing war paint, which is a sacred practice for some Native American tribes. However, the Na’vi use war paint for decorative purposes, which is not the traditional use of war paint. Additionally, the Na’vi are often shown living in harmony with nature, which is a stereotype that has been used to justify the colonization of Native American lands. While the film Avatar is not intended to be a historically accurate portrayal of Native American cultures, it is important to be aware of the potential for cultural appropriation in popular culture. When fictional characters are depicted wearing traditional clothing from real-world cultures, it is important to ensure that the portrayal is accurate and respectful. By taking into account the bits of knowledge from Bird’s work, we can more readily comprehend the power elements at play in costume design and the obligation that designers have in depicting societies precisely and deferentially.

Decolonizing Costume Design

The idea of decolonization has arisen as a pivotal system for tending to drive irregular characteristics and testing frontier heritages in different spaces, including costume design. The book “Unsettling the Colonial Places and Spaces of Early Childhood Education,” edited by Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw and Affrica Taylor offers important bits of knowledge into decolonization endeavors in education [2].

By applying the experiences from this book to the domain of costume design, we can investigate ways of decolonizing and change the training. Decolonizing costume design includes destroying designs of force and participating in conscious and evenhanded joint efforts with cultural networks. Informed assent turns into an imperative part of decolonizing costume design. It is basic to look for consent and direction from cultural networks while integrating components from their customs or images into costumes. This requires open exchange, tuning in, and grasping the meaning of cultural practices and feel [2]. Joint effort is one more fundamental component in the decolonization of costume design. By including cultural networks in the design cycle, costume designers can profit from their insight and skill. Cooperation considers more precise and conscious representations of societies, empowering the sharing of stories based on impartial conditions [2]. Aware commitment with cultural networks is major to decolonizing costume design. It requires perceiving and tending to control elements, esteeming assorted viewpoints, and effectively neutralizing the propagation of generalizations and cultural allotment. Drawing in with networks in significant ways guarantees that costume design turns into a cooperative and engaging cycle [2]. By embracing the bits of knowledge from “Agitating the Frontier Places and Spaces of Youth Instruction,” costume designers can add to the more extensive decolonization development. Through informed assent, joint effort, and conscious commitment, costume design can turn into a mechanism for cultural festival, trade, and strengthening.

Context, Intent, and Responsible Design

In the article “From Cultural Exchange to Transculturation” by George Yúdice, a reconceptualization of cultural allocation and its effect on imaginative practices is introduced (Yúdice, 2003). This article offers important bits of knowledge that can be applied to the assessment of costume design decisions, explicitly according to the job of setting, purpose, and crowd. Yúdice stresses the meaning of understanding the setting in which cultural components are acquired or consolidated. By taking into account the authentic connections, power elements, and cultural implications related with the components being utilized, costume designers can explore the intricacies of cultural allocation and settle on informed choices (Yúdice, 2003). Additionally, the goal behind integrating cultural components into costumes is urgent. Costume designers ought to basically look at their goals, guaranteeing that they line up with appreciation, deferential commitment, and the advancement of cultural comprehension. By thinking about expectation, designers can guarantee that their decisions are grounded in moral contemplations (Yúdice, 2003).

Also, the crowd for whom the costumes are made assumes a significant part. Design decisions ought to be made with a consciousness of the possible effect on the crowd’s discernments and comprehension of the addressed culture. Aversion to how costumes could build up or challenge generalizations is essential, as the crowd’s understanding can shape more extensive impression of societies (Yúdice, 2003). By consolidating the experiences from Yúdice’s article, costume designers can embrace a more dependable way to deal with their work. Taking into account the specific circumstance, aim, and crowd all through the design interaction empowers designers to go with informed decisions that exhibit cultural regard and cultivate significant commitment.

Ethical Considerations and Way Forward

The assessment of cultural appropriation t in costume design uncovers huge moral ramifications that should be basically analyzed and tended to. In view of the assessed writing, obviously advancing cultural appreciation, coordinated effort, and mindful design rehearses is urgent in alleviating the adverse consequences of cultural allocation. Cultural appropriation in costume design raises moral worries as it frequently sustains generalizations, disregards cultural legacy, and adds to the deletion of minimized societies. To resolve these issues, designers ought to take part in contemplation and self-reflection, taking into account the potential damage brought about by appropriating components without grasping their cultural importance (Bird, 1998). Advancing cultural appreciation is fundamental for mindful design rehearses (Figures 1-9).

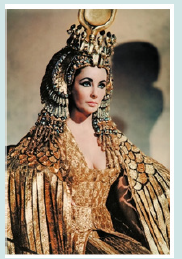

Source: The secrets behind Elizabeth Taylor’s golden dress in Cleopatra by Vouge

Figure 1: Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra in Cleopatra (1963). Taylor’s portrayal of Cleopatra, an Egyptian queen, has been criticized for being whitewashed. The costume she wore, which included a revealing dress and elaborate headdress, was also seen as appropriative.

Source: A member of the crowd at Glastonbury festival, 2014. Photograph: Ollie Millington/Redferns via Getty Images

Figure 2: A picture of a Native American headdress being worn by a non-Native actor. This is a common example of cultural appropriation, as Native American headdresses are sacred objects that have a complex cultural significance. When worn by non- Native people, they are often used to portray Native Americans in a stereotypical or inaccurate way.

Figure 3: picture of a group of people from different cultures wearing traditional clothing from their respective cultures. This picture shows how clothing can be used to celebrate cultural diversity. When people from different cultures come together and wear traditional clothing from their respective cultures, it can be seen as a way of showing respect for each other’s cultures and traditions.

Source: Johnny Depp’s Tonto misstep: Race and “The Lone Ranger” by salon.com 2013/07/03

Figure 4: Johnny Depp as Tonto in The Lone Ranger (2013). Depp’s portrayal of Tonto, a Native American character, has been criticized for being inaccurate and stereotypical. The costume he wore, which included a headdress and war paint, was also seen as appropriative.

Source: Film “Avatar 2009”

Figure 5: A picture of a Na’vi warrior wearing war paint. This is an example of how the Na’vi are portrayed inaccurately in the film Avatar. War paint is a sacred practice for some Native American tribes, but the Na’vi use it for decorative purposes.

Source: Powwow at Floyd Bennett Field, on 2 June 2013 in Brooklyn, New York, USA

Figure 6: This picture shows a group of women wearing traditional Indigenous Canadian clothing. The women in the picture are all of different ages and backgrounds, but they are all wearing clothing that reflects their shared Indigenous heritage.

Source: www.bing.com

Figure 7: This picture shows a group of children wearing costumes that represent different cultures around the world. The children in the picture are all of different races and ethnicities, but they are all wearing costumes that celebrate the diversity of human cultures.

Source: California Border Region Digitization Project

Figure 8: This picture shows a group of people wearing sombreros and ponchos. These are traditional Mexican garments that are often worn as costumes during Cinco de Mayo. However, Cinco de Mayo is not Mexico’s Independence Day, and wearing these garments as costumes can be seen as cultural appropriation.

Source: Geisha costume(Fashion Nova)

Figure 9: This picture shows a woman wearing a geisha costume. Geishas are traditional Japanese entertainers who are trained in the arts of music, dance, and conversation. Wearing a geisha costume as costume can be seen as cultural appropriation, especially if it is worn in a way that is disrespectful or inaccurate.

Designers ought to put resources into training and cultural mindfulness, developing comprehension they might interpret different societies and their verifiable settings. By recognizing and regarding the cultural implications behind the components they integrate into their designs, designers can encourage a more educated and deferential methodology [1]. Cooperation is a crucial part of capable design rehearses. Designers ought to effectively look for coordinated efforts with cultural networks, including them in the design cycle. This joint effort guarantees precise representations and supports shared accounts, enabling cultural networks and advancing common regard [2]. Capable design rehearses additionally require getting educated assent while consolidating cultural components. Looking for consent, direction, and contribution from cultural networks shows regard for their cultural legacy and values. By including their voices and points of view, designers can cultivate a more comprehensive and participatory methodology (Geczy and Karaminas, 2013).

All in all, the basic assessment of cultural apportionment in costume design features the significance of moral contemplations and mindful practices. By advancing cultural appreciation, cooperation, and informed assent, designers can add to a more deferential and comprehensive industry. To address cultural appropriation successfully, progressing exchange, instruction, and mindfulness are vital. Designers, industry experts, and partners ought to participate in nonstop learning, reflection, and open discussions about cultural representation and the effect of design decisions. By cultivating a culture of cultural responsiveness, regard, and inclusivity, we can endeavor towards an all the more morally cognizant future in costume design [3-10].

Conclusion

All in all, the assessment of cultural assignment in costume design, drawing upon the explored writing, has revealed insight into significant discoveries and experiences. The vital action items from the examination feature the meaning of continuous discourse, schooling, and attention to really resolve the issue of cultural allocation in costume design. The writing audit has uncovered that cultural appropriation in costume design can propagate generalizations, build up power awkward nature, and add to the deletion of underestimated societies. To counter these adverse consequences, cultivating an environment of open discourse and engagement is fundamental. Training assumes a basic part intending to cultural allocation. Designers need to develop how they might interpret different societies, their accounts, and the meaning of cultural components. This information furnishes designers with the fundamental apparatuses to settle on informed decisions and stay away from misrepresentations. Additionally, progressing discourse is fundamental for establishing a comprehensive and aware design climate. Taking part in discussions with cultural networks, looking for their viewpoints, and effectively including them in the design cycle can prompt joint efforts that advance the cultural appreciation and engage those whose societies are being referred to. Mindfulness is one more critical part of battling cultural appropriation.

By bringing issues to light inside the business and among the overall population, we can cultivate a more noteworthy comprehension of the intricacies encompassing cultural representation in costume design. This mindfulness can energize decisive reasoning and dependable design rehearses. To address cultural assignment really, a diverse methodology is required. Proceeded with exchange, instruction, and mindfulness should be combined with moral contemplations, joint effort, and informed assent. By incorporating these standards into the design cycle, designers can explore the intricacies of cultural apportionment even more dependably. All in all, continuous exchange, schooling, and mindfulness are basic to tending to cultural appropriation in costume design. By taking part in these practices, designers can advance cultural appreciation, keep away from unsafe generalizations, and add to a more comprehensive and deferential imaginative industry. By and large, this survey highlights the requirement for proactive and persistent work to challenge cultural apportionment, encouraging a design scene that celebrates cultural variety while regarding and regarding the networks and customs from which motivation is drawn.

References

- Deloria PJ (1998) Playing indian. Yale University Press, USA.

- Pacini-Ketchabaw V, Taylor A (2015) Introduction Unsettling the Colonial Places and Spaces of Early Childhood Education in Settler Colonial Societies.

- Nelson EH (1998) Dressing in Feathers: The Construction of the Indian in American Popular Culture. The Journal of American Culture 21(1): 83.

- Geczy A (2013) Fashion and Orientalism: Dress, Textiles and Culture from the 17th to the 21st Century. A&C Black.

- Nxumalo F, Vintimilla CD, Nelson N (2018) Pedagogical gatherings in early childhood education: Mapping interferences in emergent curriculum. Curriculum Inquiry 48(4): 433-453.

- Pacini-Ketchabaw V, Taylor A, Blaise M, de Finney S (2015) Learning how to inherit in colonized and ecologically challenged life worlds in early childhood education. Canadian Children 40(2).

- John R (2019) Unsettling the colonial places and spaces of early childhood education.

- Taylor A (2017) Beyond stewardship: Common world pedagogies for the Anthropocene. Environmental Education Research 23(10): 1448-1461.

- Rogers RA (2006) From cultural exchange to transculturation: A review and reconceptualization of cultural appropriation. Communication theory 16(4): 474-503.

- Maina-Okori NM, Koushik J R, Wilson A (2018) Reimagining intersectionality in environmental and sustainability education: A critical literature review. The Journal of Environmental Education 49(4): 286-296.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...