Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4595

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-4595)

An Overview into the Issue of Sustainability within Fashion Apparel Volume 5 - Issue 3

Jamal Majid*

- Jamal Majid*

Received:December 05, 2022 Published: January 11, 2023

*Corresponding author: Jamal Majid, Senior Lecturer Fashion Business, Level Five Year Manager, Manchester Fashion Institute, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

DOI: 10.32474/LTTFD.2023.05.000211

Abstract

In the context of planet damage and being at the cusp of irrevocable environmental decline the need for organizations to pursue a more sustainable agenda is arguably now a necessity for fashion brands rather than an indulgence. Exploration into the fashion industry reveals that some progression in relation to sustainability is certainly apparent and indeed heavily marketed. Emerging and non-developed nations who are key manufacturers of apparel are attributed to be the worst perpetrators and indeed most affected by unsustainable practice, but it maybe the direction of causality for this phenomenon could be attributed to more western demand driven economies who are not as incentivized by consumers to indulge in ethical and sustainable practices. The article infers that the universal stakeholder commitment assisted with technology is warranted, for sustainability to be implemented with all process’s incumbent within apparel concept to consumer purchase.

Keywords: CSR: Corporate Social Responsibility; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

The fashion industry is noted to be one of the biggest polluters on the planet which contributes to sustainability in many areas [1]. Fashion retailers are embarking on strategies in which to actively alleviate unsustainable practices [2]. But it can be argued that the rhetoric often contradicts the reality that is apparent in the business world, which could be attributed to the lack of clarity in relation to the actual concept of sustainability itself [3]. The meaning of sustainability remains elusive, such an instance has created a situation in which enterprises are interpreting in many ways, such as that of environmental stewardship to corporate social responsibility (CSR) [4]. Nevertheless, it can be contended that ‘sustainability’ has three dimensions (Environmental, Social and Economic) these are arguably required to be infused within an organization’s DNA for its impact to be truly effective [3]. However, it should be acknowledged that it is somewhat simplistic to assume that all three aspects of sustainability work in unison with one another as the tenuous balance of economic, social, and economic objectives for sustainable development is often untenable for most organization that exist in a profit driven environment [4]. This instance, complemented with the practice of decentralized policies in non-developed nations within the textile manufacturing sector and the growth of small-scale labour-intensive industries often results in little attention being given to sustainable issues such as that of the protection of workers, the use of hazardous chemicals, investment into new fabrics and pollution [5].

Environmental

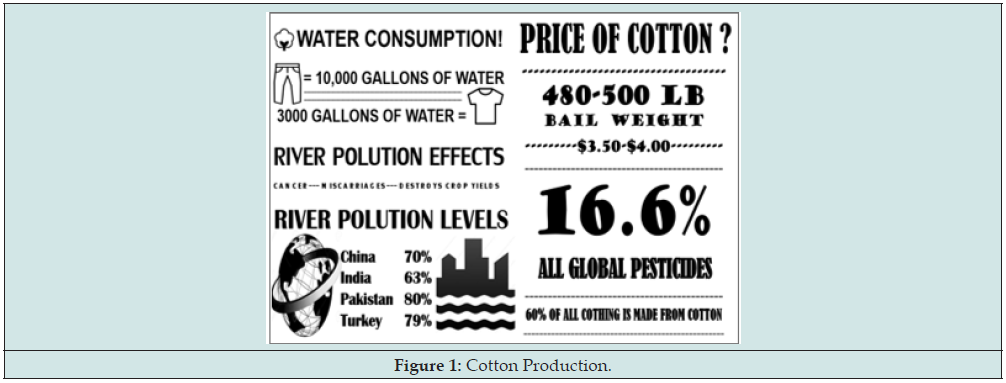

The environmental aspect of sustainability considers the impact of organisational activities on natural resource depletion, pollution and emission management, waste/energy, and resource management etc. Chapagain et al. [6] contends that the fundamental product used by all businesses is arguably that of cotton production accounts for a sixth of all pesticides used globally, is extremely water intensive, highly polluting, and extremely cancerous (Figure 1). Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) stipulates 20,000 individuals die of cancer and suffer miscarriages due to chemicals sprayed on cotton [7]. The growth of the cotton plant requires high levels of water and as sixty percent of all apparel is constructed of cotton, high yields are needed. Water is not only needed to cultivate the plant, but vast amounts are also needed to process and dye the cotton, so that the raw material is ready to be transported for manufacture in to apparel [8]. Hence, the production of cotton which is predominately within non-developed countries is highly water intensive, hazardous, pollutive and has contributed to global decline of consumable river water [9]. The instance of global warming has heighted the instance of water scarcity and the need for regreening to occur. Re-greening is devoted to promoting the sequestration of carbon which facilitates cooling soil, stimulating humidity and rainfall [10]. Emerging nations the likes of Pakistan are engaging in activities to combat climate change and improve water filtration by committing to plant ten billion trees, one billion of which has already been planted in 2014 [11]. The United Nations reports that governments of Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam have all collaborated to join forces to reduce hazardous chemicals in their textile industries [12]. Further commitment by nations to such activities and exploration in more sustainable or alternative fibres to that of cotton could serve to alleviate the environmental impact caused by the fashion industry [13].

The ability to change to alternative fabric created from the production of cellulose fibers such as Hemp is often advocated to be the ideal replacement to produce cotton [14]. However, it should be acknowledged that greater exploration into this reveals that this is also riddled with ambivalence, as sustainable hemp production is dependent on large scale financial investment in innovation and integration of the latest advances in fields of genomic, proteomic and metabolomics warranted to create uniform yields [15]. The commitment by business to embark on using other source material is often piecemeal and results in heightening other areas of sustainability, but to curb greater environmental damage alternatives are warranted. Alternative fibres from oranges, mushrooms and pineapples are being developed but their fullscale commercial is questionable. Premium apparels are exploring alternatives to some commercial success with the likes of Gucci being the first luxury brand to use ‘ECONYL’ which is a regenerated nylon yarn made from abandoned fishing nets and carpets. This raises the issue of it is the top-down approach that is warranted within the industry and if the custodians of real comprehensive sustainable practice should be the domain of premium apparel brands [16].

Social

The social aspect of sustainability reflects on the social obligation of the organization to the communities by managing issues such as that of poverty, orientation discrimination, clean water, education etc. Fast growing and large-scale apparel production have been attributed to the blame for labour exploitation and environmental damage [17]. The scarcity of water and the pollution of rivers consequently garment production, usually in many developing nations has created a circumstance in which river pollution is rife accompanied with associated dieses such as cancer (Figure 1). Despite the rhetoric in relation to fair pay and treatment of staff, a real living wage is not still apparent in many developing nations and the commitment of apparel business to such was apparent in the complete abandonment of such concerns in the pandemic, within which the social consequence of poverty because of cancelling orders for workers involved in production was not even paid lip service to [18]. Further explorative analysis reveals that it is not possible for many fashion brands irrespective of retail tier to illustrate that real living wages are being paid to any worker within their supply chain outside of them headquarter which are predominantly located within the apparel retailer’s western countries of origin [19]. Such an issues illustrate the underpinning exploitative capitalist framework within which western business often operates as well as the sporadic engagement in sustainable practice. This is manifest in the Human right’s violation are still arguably as prominent as ever within the fashion supply chain. Instances such as that of Myanmar in which fashion apparel companies the likes of H&M, Gap, Adidas, Muji, Uniqlo, Tommy Hilfiger, Calvin Klein, etc all being complicit in the purchase of cotton as a direct consequence of forced labour in concentration camps [20]. Irrespective of such an instance, such organizations are still simultaneously advertising their sustainability credentials by virtues of having written policies such as that of adhering to the Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) and elements of ranges made from sustainable materials [19]. Such an instance illustrates the inherent dichotomy in relation to issue of sustainability between rhetoric and reality of fashion apparel brands, with brands such as H&M being examples of such perpetrators [20].

Economic

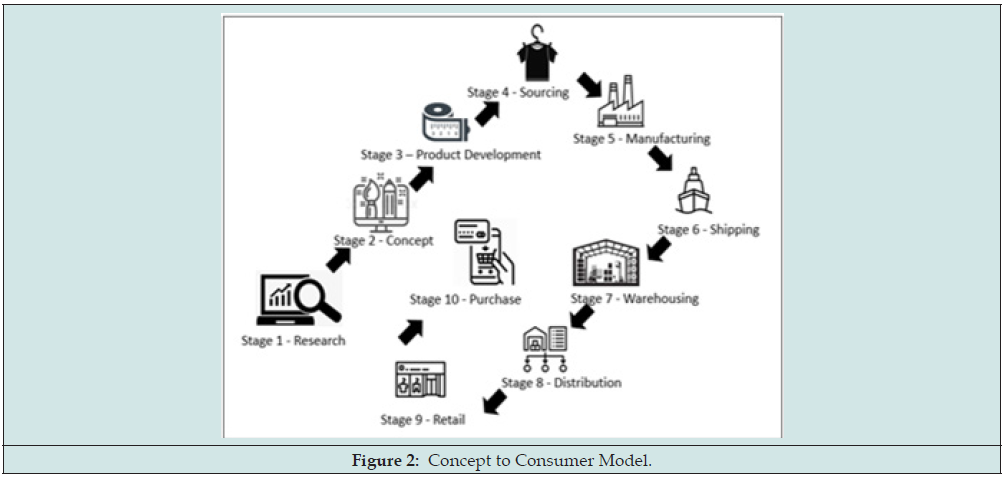

The economic aspect of sustainability is related to concerns on the viability of the organization to survive financially amidst a competitive marketplace and raises issues, such as the ability of an organization to obtain a return on investment (ROI) and indeed the ability to sustain CSR initiatives indefinitely. The likes of McKinsey [22] advocate that there is a financial advantage to the formation of transparent fashion brands as it will be preferential for a new-aged, enlightened consumer. The beneficial aspects of pursuing a more sustainable agenda from the initial concept through to the actual consumer is riddled with potential benefit if only fashion brands were to actively pursue them (Figure 2). Businesses are discovering that sustainable pursuits can indeed aid them to reduce costs, thus effectively increasing their profits. This is apparent in using more computer systems to aid design and more effective pattern cutting, to reduce waste and time in making costly and time prototypes which heighten ecological footprints [23]. The likes of Gucci after consultation and review of procedure by Gen Z task group reformed cutting procedures to reduce waste and make additional products from traditionally discarded leather [15]. The instance of sourcing and manufacturing from more ethical suppliers and producing brands of more superior quality are appealing to consumers who are willing to pay a higher price point for ethically produced apparel made from more sustainable fibres, fashion brands the likes of Patagonia, House of Sunny, SZ Block prints and Bridsong are amidst the most successful [24]. However, it should be acknowledged that such truly sustainable fashion apparel enterprises only constitute a very small minority of all fashion enterprises within which there is an absence of the most affluent fashion apparel brands who can arguably afford to emulate and indeed be at the forefront of sustainable practice. The way in which more enterprises are, and indeed other brands can embark on the pursuit of more sustainable enterprise is by the successful development of more strategic innovative partnerships [25] with the inclusion of suppliers to appraise design aided with the introduction integrated computer systems has been proven create innovative new products, from design to merchandising and planning to sourcing and supply chain management [26]. The shift to a more agile and intelligent sourcing model has the potential to reduce waste, foster efficiencies and produce apparel in quantities required rather than predicted inaccurately. Perhaps the digitization of the fashion world and the onset of new technology could usher in an era of truly sustainable practice if indeed all stakeholders in fashion become truly committed to sustainability [27].

Conclusion

The summation of some of the key factors entrenched within the three constituent elements of sustainability of (Environmental, Social and Economic) reveals that although there is some progression, such developments are often piecemeal and warrant a lot more commitment to be more complicit to sustainable business practice.

The reluctance of fashion apparel businesses to pursue of a sustainable agenda could be attributed to the absences of the prerequisites necessary, which are that of substantial economic, technological, and financial support from developed countries and from the international community [28]. Furthermore, support is needed to compensate for the economic losses associated with the pursuit of a sustainability agenda, especially in non-developed nations within Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asian countries within which the provision to pursue such initiatives is lacking. Within the context of global economic decline, the ability and indeed desire to pursue sustainable objectives let alone change the DNA of an organization towards sustainability, is improbable unless there is holistic stakeholder involvement. One of the key attributes towards this is the necessity for government legislation and real sanctions against organizations who are lacking in sustainable credentials [29]. The EU Commission introduction of the possibility of trade sanctions on trade partners who breach the Paris Climate Agreement or the International labour Organization (ILO) fundamental principles and governments of Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam all collaborating to reduce hazardous chemicals in their textile industries [29] is a possible step in the right direction. It is also important there is a true shift in consumer preference towards more sustainable practice rather than wavering commitment brought about as price difference [30- 33]. Hence, it becomes apparent that only with true stakeholder commitment can sustainability be a reality in the fashion industry.

References

- Le N (2002) The impact of fast fashion on the Environment. The Trustees of Princeton University.

- Khandual A, Pradhan, S (2018) Fast Fashion, Fashion Brands and Sustainable Consumption Publisher: Springer. Location USA.

- Pazienza M, De Jong M, Schoenmaker D (2022) Clarifying the Concept of Corporate Sustainability and Providing Convergence for Its Definition. Sustainability 14: 7838.

- Jerónimo Silvestre W, Antunes P, Leal Filho W (2016) The corporate sustainability typology: analysing sustainability drivers and fostering sustainability at enterprises. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, Issue Number 24(2): 1-21.

- Asmorojati A W, Nur M Dewi IK, Hashim H (2022) The Impact of COVID-19 on Challenges and Protection Practices of Migrant Workers' Rights. Bestuur. UNS Universitas Seblas Maret 10(1): 46-56.

- Chapagain AY, Hoekstra B, Saveenije, HHG, Gautam R (2006) The water footprint of cotton consumption: An assessment of the impact of worldwide consumption of cotton products on the water resources in cotton producing countries. Ecological Economics. 60(1): 187-203.6

- Khawani M P, Khatwani P A (2017) Indian Textiles: Its sustainability and global sourcing. International Journal of Recent Innovation in Engineering and Research 2(7): 26-29.

- Gonzales, J (2022) Blue Jeans: An iconic fashion item that’s costing the planet dearly Mongabay Series: Covering the Commons, Planetary Boundaries.

- Webber M, Barnett J, Chen Z, Finlayson B, Wang M,Chen, DLi TM, Wei T, Wu S & Xu H (2008) The Yellow River in transition. Environmental. Journal of Science Policy 11(5): 422-429.

- Metic J, Pigosso D CA (2022) Research avenues for uncovering the rebound effects of the circular economy: A systematic literature review. The Journal of Cleaner Production 368(25): 1-19.

- Stockholm (2015) Pakistan’s Ten Billion Tree Tsunami leading the way in ecosystem restoration decade.

- UNEP (2022) Emissions Gap Report 2022, United Nations Environment Programme.

- Nabi G,Murad, A Khan S, Sunjeet K (2019) The crisis of water shortage and pollution in Pakistan: Risk to public health, biodiversity, and Ecosystem. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 26: 10443-10445.

- Abdulla, H (2022) Will hemp replace cotton as must-have fibre? The sustainability benefits of hemp are unquestionable. But will it replace cotton? Just Style Online.

- Liberalato D (2003) Prospect of hemp utilization in the European Textile Industry. Agro-industria Journal 2 (3): 147-148.

- Equilibrium (2021) Planet - Gucci of the Grid - A vision of circularity promoting the regeneration of materials and textiles.

- Akhter S, Rutherford S, Chu C (2017) What makes pregnant workers sick: why, when where and how? An exploratory study in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. Reproductive Health 14(1): 142-147.

- Cheek WK, Moore CE (2006) ‘Apparel sweatshops at home and abroad: Global and ethical issues’, in, Journal of family and consumer Sciences 95(1): 9-18.

- Kim EH, Lyon TP (2015) Greenwash vs. Brown wash: Exaggeration and Undue Modesty in Corporate Sustainability Disclosure. Organization Science 26(3): 705-723.

- Kelly, A (2020) The Guardian Newspaper Online. ‘Virtually entire' fashion industry complicit in Uighur forced labour”.

- Shen B (2014) Sustainable fashion supply chain: Lessons from H&M. Sustainability 6(9): 6236-6249.

- McKinsey & Co (2022) The State of Fashion 2022. The Business of Fashion.

- Wackernagel M, Onisto L,Bello P,Linares A.C,Falfan, I.S.L,Garcia, J.M,Guerrero, A.I.S, Guerrero MGS (1999) National natural capital accounting with the ecological footprint concept. Ecological. Economics 29(3): 375-390.

- Sustainably Chic (2022) The most affordable and ethical brands in 2022.

- Broman G, Robèrt KH, Basile, G, Trygg L (2016) The new approach highlights the opportunity for novel business model design for future sustainable success. The Journal of Cleaner Production 140: 1-21

- Giunipero LC, Fiorito SS, Pearcy DH, Dandeo L (2001) The impact of vendor incentives of quick response. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 11(4): 359-376.

- Steurer R, Langer ME, Konrad A, Martinuzzi A (2005) Corporations, Stakeholders and Sustainable Development I: A Theoretical Exploration of Business-Society Relations. Journal of Business Ethics 61: 263-281.

- Dahlbo H, Aalto K, Eskelinen H, Salmenperä H (2017) Increasing Textile Circulation - Consequences and Requirements. Sustainable Production and Consumption 9: 44-57.

- Rother S (2018) ASEAN Forum on Migrant Labour: A space for civil society in migration governance at the regional level? Asia Pacific Viewpoint 59(1): 107-118.

- Ranalli, Paolo & Venturi, Gianpietro (2004) Hemp as a raw material for industrial applications. Euphytica 140: 1-6.

- Bick R, Halsey E, Ekenga CC (2018) The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. The Journal of Environmental Health 92(17).

- Di Candilo M, P Ranalli, C Bozzi, B Focher, G Mastromei (2000) Preliminary results of test facing with the controlled retting of hemp. Industrial Crops Products 11: 197-203.

- Bergman MM, Bergman Z, Berger L (2017) An Empirical Exploration, Typology, and Definition of Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 9(5): 753-762.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...