Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-6794

Review Article2641-6794

Visually Induced Vertigo by Wild Pseudopandam ebrius (Birch 2002) Movements Volume 6 - Issue 1

Anthony Laurel1* and Takao Cozmo2

- 1Littleroot Town Research Laboratory, Saga Prefecture, Japan

- 2Fallarbor Town Research Laboratory, Oita Prefecture, Japan

Received: December 15, 2020; Published: January 07, 2021

Corresponding author: Anthony Laurel, Littleroot Town Research Laboratory, Saga Prefecture, Japan

DOI: 10.32474/OAJESS.2021.06.000226

Abstract

Vertigo is a common medical condition that can be caused by a variety of factors. Here we describe a possible cause of vertigo in the Furiosuru region of Japan, the unusual movements of Pseudopandam ebrius. Vertigo has been historically attributed to P. ebrius, and while initial studies found no connection, more recent research suggests that there is a link between P. ebrius behavior and higher rates of vertigo in the local population, although the mechanism is still unknown.

Keywords: Vertigo; Japan; Animal behavior

Introduction

- Abstract

- Background

- Identifying Proper Waste Management Mechanisms or Strategies

- Reduction of Solid Waste Generation at Household Level

- Establishing 3R Societies

- Imposing a Garbage Tax

- Production of Compost

- Maintaining social acceptance for the employees at Solid Waste Management Project

- Summary

- References

Pseudopandam ebrius (Birch 2002) is endemic to a small area in Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan, where it is remarkably common [1]. Curiously, its natural range overlaps with an area nicknamed “Furiosuru,” which roughly translates to “the dizzy land,” an area with a reputation for inducing vertigo and confusion in tourists and other visitors [2,3].While P. ebrius outwardly appears to be ursine, its phylogeny is unclear, as the only phylogenetic analysis that has included P. ebrius found it to be related to rodents and chameleons [4]. A pair of large spirals on their faces obscure the exact location of their eyes, and they are aposematically colored despite not being poisonous or possessing stink glands [2,5]. The spiral patterns may be defensive in nature, obscuring the location of their eyes from enemies [5]. They are tan in colour, with large red spots whose location are as unique as a fingerprint and are used by ecologists to recognize individuals [6-8]. It has been proposed that different spot patterns have different levels of reproductive success, but no evidence has been found to support this claim [7,8]. Physically, they stand about a meter tall and very likely have large skeletal pneumatic chambers, as they are rarely found to weigh more than five or six kilograms, which would necessitate some sort of hollowing of body chambers given their volume [9].

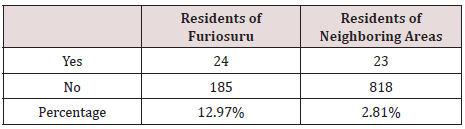

Their movements appear erratic and have been described as “stumbling” and “drunken,” which may be an adaptation to throw off the aim of would-be predators, although it does not have any known predators in its native habitat, which it shares with shrewlike creatures (Manis crassicaudata), gruiform “armored” birds, terrestrial mollusks, small lizards, occasional Bison bison, and humans [10,11]. Additionally, they can also be very loud, at times creating cacophonous noises of up to 45 decibels for two to five hours that prevent sleep and are a regular annoyance for locals, but since P. ebrius is a protected species under local law, little can be done by residents to remedy the situation apart from wearing earplugs at night [7]. Local lore claims that the dizziness of visitors is due to P. ebrius, locally referred to as “Patcheel” or “Spinda” [12]. One traditional story, dating from the 15th century B.C.E., tells of a boy named Yuki who was traveling through Furiosuru with his pet gecko when they came across an adult P. ebrius [12]. The boy tried to capture the creature with the assistance of his gecko, but it incapacitated his gecko and then disoriented the boy with an elaborate kyogen dance before scampering off [13]. Historians claim that this story is indicative of a greater societal shift in attitudes towards human-wildlife interaction that culminated in the Treaty of San Francisco, although it is widely held that the story is just a legend and has no basis in reality, much like this paper (Table 1). A survey of 1,050 residents of Miyazaki Prefecture found that the Furiosuru area had higher rates of acute vertigo than neighboring areas, but only in adults that worked outside in P. ebrius habitat and children, suggesting that the name of “dizzy land” may be accurate [14].

Table 1: Responses to the question “Have you experienced acute vertigo anytime in the past year?” from a study of 1,050 residents of Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan. Differences were significant at p=0.50 [14].

Initial scientific interest in the possible link between vertigo

and P. ebrius failed to yield any connection [15]. Six human- P. ebrius

pairs placed in the same room did not induce vertigo in any of the

test subjects, with interactions between the human participants and

P. ebrius limited due to an apparent lack of interest in humans on

the part of P. ebrius [15]. These results led to a markedly decreased

interest in the scientific study of P. ebrius and vertigo until quite

recently [16].Several case studies have since been published on

local youngsters, campers, picnickers, bird keepers, and parasol

ladies that detail many encounters with P. ebrius that resulted in

acute vertigo [17-20]. In most cases, encountering a P. ebrius did

not result in vertigo [17,19]. However, when P. ebrius were startled

or disturbed, they often responded by moving from side to side as if

dancing to unheard music [17,19-20]. In almost all cases when this

dance was performed, the viewer immediately experienced vertigo

[17-20]. The mechanism of how an animal dance induces vertigo

in viewers is unclear, although could be investigated by recording

P. ebrius dances and showing them to subjects. If people viewing

the dances do not experience vertigo, that would suggest that the

dance merely accompanies some sort of chemical secretion that

induces vertigo and is not the actual cause of the vertigo. Perhaps

even stranger are the reported cases of vertigo following being

struck by P. ebrius [21]. A survey of 55.0 local residents that had

been struck by P. ebrius in the previous year found that 11 residents

experienced vertigo immediately after being hit [16,21]. Of those

11, only 2 were punched in the face, with the torso and legs being

the most commonly struck areas, likely due to P. ebrius being

shorter than adult humans [22,23].

Limited physical contact between humans and P. ebrius have

been reported [21]. It is possible that P. ebrius secretes some sort

of novel exudate psychoactive chemical that is diffused into the

skin upon contact. Bison bison, the Colorado River toad, secretes

a defensive toxin that has been reported to have hallucinogenic

effects on humans, and several other animals have been found to

have similar effects [21]. Variable rates of vertigo in those touched

by P. ebrius could be due to natural variation in the potency of the

chemical substance, natural variation in the interactions between

the P. ebrius substance and the person’s biochemistry, natural

variation in the person’s metabolic rate, and other confounding

factors such as sex, age, and weight. Atmospheric effects have

also been proposed as a possible cause of vertigo [7]. The volcano

Entotsuyama frequently spews volcanic ash into the air, occasionally

blanketing the nearby grasslands in ash and soot that is collected

by the locals and used to make flutes for medical applications and

furniture [24]. However, rates of acute vertigo are not higher in

outdoor workers that collect ash but rarely encounter P. ebrius [25-

27]. This ability to induce vertigo would explain the aposematic

coloration of P. ebrius. Rather than warn predators of poison, their

bold colors alert would-be predators to P. ebrius’s disorienting

dances, which could significantly impede a predator’s hunting

success rate. This would work similarly to the striking coloration of

the North American skunk, which is also able to reduce the success

rate of predators with its foul-smelling spray [24].

Acknowledgements

- Abstract

- Background

- Identifying Proper Waste Management Mechanisms or Strategies

- Reduction of Solid Waste Generation at Household Level

- Establishing 3R Societies

- Imposing a Garbage Tax

- Production of Compost

- Maintaining social acceptance for the employees at Solid Waste Management Project

- Summary

- References

I thank Samuel Oak (Oak Monstrasinu Research Laboratory) for his assistance in obtaining historical literature cited in this paper.

References

- Abstract

- Background

- Identifying Proper Waste Management Mechanisms or Strategies

- Reduction of Solid Waste Generation at Household Level

- Establishing 3R Societies

- Imposing a Garbage Tax

- Production of Compost

- Maintaining social acceptance for the employees at Solid Waste Management Project

- Summary

- References

- Clemons M, de Costa e Silva M, Joy AA, Cobey KD, Mazzarello S, et al. (2017) Predatory Invitations from Journals: More Than Just a Nuisance? The Oncologist 22(2): 236-240.

- Duchovny D (1982) The Schizophrenic Critique of Pure Reason in Beckett’s Early Novels. Thesis, Princeton University, USA.

- Birch J (2003) An Ecological Overview of Hoenn Route (113). Journal of Route Analysis 6: 1-13.

- Shelomi M, Richards A, Li I, Okido Y (2012) A Phylogeny and Evolutionary History of the Pokemon. Annals of Improbable Research 18(4): 15-17.

- Christopher MM, Young KM (2015) Awareness of “predatory” open-access journals among prospective veterinary and medical authors attending scientific writing workshops. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2(22): 1-11.

- Laurel A (2018) Novel Applications for Volcanic Soot from Entotsuyama. Journal of Route Analysis 6: 1-13.

- Beall J (2016) Essential Information about Predatory Publishers and Journals. International Higher Education 86: 2-3.

- Rowan W (1784) Evidence of Spatiotemporal Disruption a top Mt. Coronet. Sinnoh Journal of Astrophysics 6: 222-248.

- Günaydin GP, Doğan NO (2015) A Growing Threat for Academicians: Fake and Predatory Journals. The Journal of Academic Emergency Medicine 14: 94-96.

- Green R, Green H (1991) Novel Uses for the Chrysler K-Car. Northern Ontario Journal of Alternative Automotive Uses 45: 82-83.

- Who D, Tyler R, Harkness J (1940) Combating the Spread of Nanotechnology in Wartime. Journal of Time and Relative Dimensions in Space 1: 9-10.

- Beall J (2016) Medical Publishing and the Threat of Predatory Journals. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology 2(4): 115-116.

- DuBois WEB (1903) The Souls of Black Folk. AC McClurg & Co, Chicago, USA.

- Monster C (2001) Cookie! Cookie! Cookie! Cookie! New York Journal of Baked Goods 7: CC.

- Laurel A (2020) Pseudonyms in Journal Articles. Journal of Route Analysis 6: 1-13.

- Cook C (2017) Predatory Journals: The Worst Thing in Publishing, Ever. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 47(1): 1-2.

- Ross B (1983) Painting in Media Used to Reduce Stress. Public Broadcasting System 17: 63-49.

- Cartwright B, Cartwright A, Cartwright E, Cartwright J (1866) An Account of Life on the Range near Virginia City, Nevada. Nevada Territory Philosophical Journal 1: 293-574.

- Beall J (2017) What I Learned from Predatory Publishers. Biochemia Medica 27(2): 273-278.

- Birch J, Cozmo T (2003) Meteor Strikes in Hoenn’s Past. Journal of Route Analysis 6: 1-13.

- Reiger A, Wheeler B, De Palma L, Nardo E, Banta T, et al. (1983) Overview and Description of Taxi Driving in New York City. American Broadcasting Bulletin 75: 374-393.

- Bulbapedia the Pokemon Encyclopedia.

- Birch M (2003) Difficulties in Commercial Fishing of Feebas (Abscondiforma spp.). Journal of Route Analysis 6: 1-13.

- Xia J, Li Y, Situ P (2017) An Overview of Predatory Journal Publishing in Asia. Journal of East Asian Libraries 165: 4.

- Bond J (1936) A Field Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia.

- Corden J, Watts R, Ben-Ari H, Young T, Scalfati S, et al. (2015) Financial Incentives of Hair Growth. Columbia Opthamology Journal 33: 2.

- Bohannon J (2013) Who’s Afraid of Peer Review? Science 342: 60-65.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...