Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-5910

Research Article(ISSN: 2638-5910)

Screening for Malnutrition in Older Hospitalised Patients in an Internal Medicine Department of a Greek Public Hospital Volume 2 - Issue 1

Ioannis Kyriazis1*, Fotios Panagiotis Tatakis2, Theodora Lappa3, Emmanuel Kalafatis2, Amalia Tsagari3, Dimitra Latsou4, Paraskevi Koufopoulou5 and Moyssis Lelekis2

- 1 Diabetes & Obesity Outpatient Clinic, KAT General Hospital of Attica, Greece

- 2 Internal Medicine Department, KAT General Hospital of Attica, Greece

- 3 Nutrition Department, KAT General Hospital of Attica, Greece

- 4 Department of Social and Educational Policy, University of Peloponnese, Greece

- 5 Department of Economics, University of Piraeus, Deputy CEO, KAT General Hospital of Attica, Greece

Received:February 04, 2019; Published: February 11, 2019

Corresponding author:Ioannis Kyriazis, Diabetes & Obesity Outpatient Clinic KAT General Hospital, Greece.

DOI: 10.32474/ADO.2019.02.000128

Abstract

Background: Malnutrition is a major public health concern that frequently tends to be unrecognized and untreated. About 1/3 of all patients in the hospital are undernourished globally. Malnutrition is significantly more common in older adults, and consequently they are in danger of suffering from malnutrition prior to their admission.

Aim: The objectives of the present study were to estimate the prevalence and severity of malnutrition, along with recent weight loss, in older adults admitted to a department of internal medicine in public general hospital in Greece. Methods: Data was collected from a total sample of 127 patients (>65 years old) recruited from the patients admitted to an internal medicine ward by conducting a cross-sectional study. Nutritional status was assessed by using the Mini Nutritional Assessment - Short Form (MNA-SF).

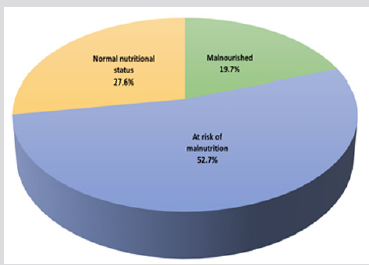

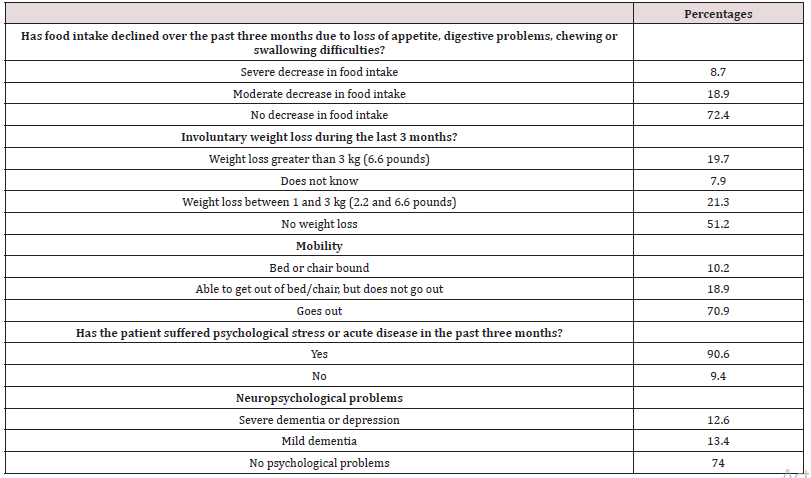

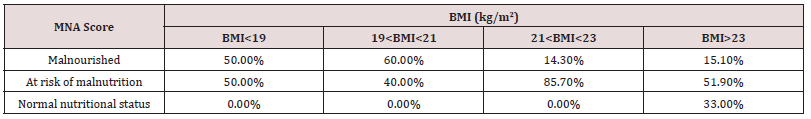

Results: The median age of participants was 78 (SD 7.2 years), and among them, 61.4% were women. The prevalence of malnutrition in the hospitalized older patients was 19.7%. According to MNA-SF, 52.7% of older patients were at risk of malnutrition, and among them, 27.6% had decreased food intake during the last three months. During the last three months, 19.7% experienced an unintentional weight loss more than three kg. Additionally, 15% of participants with a Body Mass Index (BMI) over 23 kg/ m2 were classified as malnourished, and only 33% of them were classified with no nutritional problem (p=0.003). Among the 25 malnourished older patients identified by MNA-SF, only 8 were prescribed Oral Nutritional Supplements (O.N.S).

Conclusion: The high prevalence of malnourished patients and older patients at risk of malnutrition emphasizes the need for hospitals to adopt a particular policy and a specific set of clinical protocols to identify patients at nutritional risk leading to an appropriate nutritional care plan. Early identification by a validated screening tool, could lead to an effective management of malnutrition.

Keywords:Elderly; Malnutrition; Mini Nutritional Assessment; Greece

Introduction

Malnutrition is associated with a great deal of negative clinical outcomes, including longer length of hospital stay, higher morbidity, mortality, muscle loss, impaired wound healing and increased infection and complication rates [1-5]. Although measurement of malnutrition varied depending on the hospital unit and the way of nutritional assessment, the detection of malnutrition and early nutritional management in hospitalized patients is crucial along with the treatment of underlying diseases. However, although malnutrition among hospitalized patients is not rare, it is occasionally overlooked either because medical resources, such as the availability of nutritional specialists or hospital systematic and economic support, are inadequate, or because clinicians do not consider malnutrition to be an important clinical issue [1-4,6,7].

The definition of malnutrition has been clarified by the European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) to underscore the differences between cachexia, sarcopenia (which is the loss of muscle mass and function) and malnutrition [8]. Cachexia can be defined as a “multifactorial syndrome characterized by severe body weight, fat and muscle loss and increased protein catabolism due to underlying disease(s)”. As a result, malnutrition seen in hospitalised patients is often a combination of cachexia (diseaserelated) and malnutrition (insufficient consumption of nutrients) as opposed to malnutrition alone [8]. To improve detection rate, many studies have investigated numerous methods for screening and assessing malnutrition, and the majority of these screening tools have simplicity and accuracy and are quite useful in the clinical setting [9-13]. In spite of the fact that many clinical tools are available, malnutrition prevalence remains high and the proper therapy is not always being implemented.

Malnutrition is a debilitating health condition and the prevalence remains high, especially in the acute hospital setting, with international studies reporting rates of almost 40% [14]. Malnutrition is associated with many negative clinical outcomes including depression of the immune system, impaired wound healing, muscle wasting, longer length of hospital stays, higher treatment costs and increased mortality [15-20]. Dietetic evaluation and treatment of malnourished patients have proven to be suboptimal, and as a result the frequency of such complications significantly increased. Nutrition risk screening using a validated, reliable tool is a simple and rapid way, in order to identify patients at risk of malnutrition, and provides a basis for prompt dietetic referrals [21]. It is strongly recommended that nutrition screening be widely adopted in line with published guidelines to effectively target and decrease the incidence of malnutrition in the hospital setting [22,23]. The aim of the present study was to estimate the prevalence and severity of malnutrition, along with recent weight loss, in older adults admitted, for any reason, to a department of internal medicine in a Public General Hospital in Greece.

Materials and Methods

A cross sectional study was conducted in internal medicine ward of “KAT” General Hospital of Attica. ΚΑΤ is a tertiary hospital and one of the largest hospitals in the region of Attica. In the screening and evaluation of malnutrition participated 127 patients that randomly recruited from among the patients admitted to the internal medicine ward of this hospital. Patients were eligible for study participation if they were >65 years old and had sufficient cognitive ability to participate in the study. The duration of the survey was from September 2018.

Moreover, nutritional status was assessed by using the Mini Nutritional Assessment - Short Form (MNA-SF). The MNA questionnaire is able to identify multifactorial causes of nutritional risk specifically in elderly [24-27]. This specific questionnaire consisting of 9 components grouped into six components which are anthropometry data, general status, dietary habits, self-perceived health and nutrition states. MNA-SF score over 12 means that the patient is at normal nutrition status, 8-11 is equivalent to a situation at risk of malnutrition and a score lower than 7 (score 0-7) means that the patient is malnourished.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered and analyzed in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25. The results are presented as mean values, standard deviations and percentages. In order to compare BMI (as group), gender and age (as group) χ2 (Chi squared test) or Fisher’s exact test (used when expected values were < 5) were used. The level of significance was established as a two-sided p-value= 0.05.

Results

The median age of the participants was 78.2 years old (SD 7.2), and among them 61.4% was women. 83.5% of patients had >23 BMI, 7.9% had between 19 and 21.5, 5.5% between 21 and 23 and 3.1% < 19. According to MNA-SF, 19.7% of older patients were malnourished, 52.8% are at risk of malnutrition and the rest percentage (27.6%) was malnourished (Figure 1). The mean value of MNA-SF was 9.7 (±2.4) and the majority of patients (25.2%) had mean score 12. Among the 25 malnourished older patients identified by MNA-SF only 8 were prescribed Oral Nutritional Supplements (O.N.S).

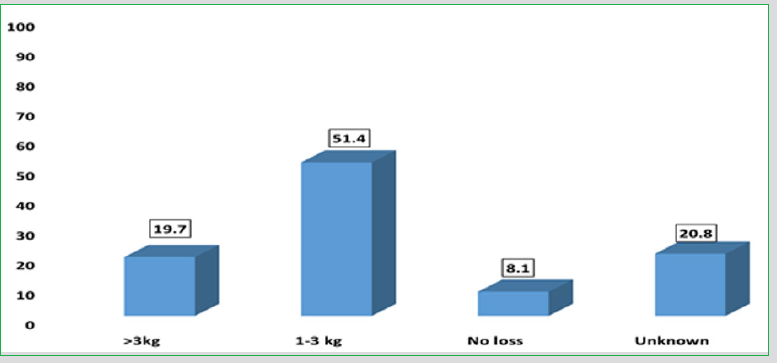

Table 1 presents the five questions of MNA- SF and the percentages of patients’ responses. Specifically, 72.4% of patients did not decrease food intake. As far as the weight loss, 19,7% of the patients experienced unintentional weight loss higher than 3 kg during the last 3 months and 51.4% between 1 -3 kg respectively (Figure 2). 70.9% had the ability to go out. Significant is the result that 90.6% of patients suffered from psychological stress or acute disease in the past three months. However, 74% declared no psychological problems.

In the Table 2 is presented the comparison between nutritional status and patients’ body mass index. To be more specific, 50% of patients with a BMI< 19kg/m2 was malnourished or at risk of malnutrition, while 60% and 40% of patients with a BMI between 19 and 21kg/m2 (19< BMI<21) was malnourished or at risk of malnutrition, respectively. Nevertheless, it was estimated that 85.7% of patients with a BMI between 21 and 23kg/m2 are at risk of malnutrition, while a percentage of 51.9% of older patients with a BMI>23kg/m2 are at risk of malnutrition. Only 15.1% of participants with a BMI over 23kg/m2 were classified as malnourished. The relationship between the nutritional status and body mass index (BMI) was statistically significant (p=0.003). Finally, there is no statistically significant differences between MNA-SF score and gender (p=0.074) as well as age (p= 0.134).

Discussion

In this study in the internal medicine department of “KAT” General Hospital of Attica, approximately 20% of the hospitalised older patients (>65 years old) had malnutrition at the point of admission according to MNA-SF screening tool, whilst 52% were at risk for malnutrition. Our results are in accordance with international literature. In the recent study of Ghosh 31.2% of patients were malnourished and 50% at risk for malnutrition [28]. Also, in the previous study of Ranhoff, 74% scored positive for malnutrition or risk of malnutrition and only 30% were scored to have malnutrition by the nutritionist [29]. However, the study of Durán Alert and Yaxley indicated significant higher percentages compare to our results. Specifically, in the first mentioned study 42.5% were malnourished, 32.5% were at risk of malnutrition and 25% were well-nourished and in the second study prevalence of risk of malnutrition was 63% according to the MNA [30,31].

As far as the comparison between BMI and MNA-SF, our findings are in agreement with others international studies, where MNA and BMI had significant correlations (Durán Alert) [30]. A previous study demonstrated that many patients in the at-risk group already had low BMI values Jeliffe et al. [32]. Also, low BMI and weight loss were significantly associated with an increased risk of malnutrition Cereda et al. [33], Hengstermann et al. [34]. Furthermore, numerous studies that focused on the relationship of MNA with a biochemical parameter, and especially with albumin levels, had found that there is a strong relationship of MNA with albumin levels. On the other hand, total lymphocyte count (TLC) was found not to have any correlation with MNA, but it is a fact that lower scores of MNA have a relationship with an impaired immune function [35].

A previous study in the hospital unit has shown that low scores of MNA questionnaire can predict the poor outcomes, which include a prolonged length of stay (LOS), a higher frequency of discharged patients’ visits to nursing homes, and approximately three times increase in the rate of mortality. In the population of healthy elderly people, MNA can also predict the risk of malnutrition before any changes in serum protein (but not in serum prealbumin levels) occurred, and other changes are identified based on the response to the questions on the dietary intake of MNA. Thus, MNA can predict the risk of malnutrition before any significant changes in weight or serum albumin level occurred and be detected [35,36].

The validity of MNA scoring system was proven not only with the anthropometric and biochemical data but also with the body composition data. A study conducted in the Philippines found that MNA is accurate and reliable in nutritional screening and assessment of Filipino elderly patients, which was proven by the Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) data. Malnourished patients identified using MNA showed a comparative BIA data with the BIA data cutoff value 6+ for elderly with malnutrition. Malnourished patients identified by MNA showed a lower weight (43 kg vs 55 kg, P< 0.001), BMI (19.5 vs 24, P< 0.001), fat weight (12 kg vs 16 kg, P=0.001), total body water (25 kg vs 27 kg, P=0.005), body cell mass (6 kg vs 9 kg, P=0.002), and body cell mass percent (13.5% vs 17%, P=0.01) and higher total body water percent (59% vs 53%, P=0.005), and showed no significant difference in fat percent (29% vs 31%, P=0.169) [35-37].

Moreover, a study in Cairo showed that an increased prevalence of malnutrition was identified by MNA accompanied by a decreased functional capacity as determined by using the activity of daily living and instrumental activity of daily living scales [38]. Nevertheless, despite these benefits of MNA, the sensitivity is still in doubt because MNA has been related to a higher risk of overdiagnosis [39]. Furthermore, the need of caregiver’s help to complete MNA, especially for the questions on weight loss, and cognitive or disabilities evaluation, is a limitation in using MNA. Nonetheless, MNA has been used in most of the studies on the nutritional status of elderly people, and it has been recommended to be used as an evidence-based screening tool for the elderly patients.

Conclusion

Malnutrition is prevalent across the world and it is a real burden on patients and health care systems. Despite the enormous advances in medicine and clinical care, the correction of a patient’s nutritional status tends to be overlooked or not considered as an adequate medical priority in the modern hospital settings [35]. The treatment of malnutrition requires a malnourished patient to be identified via either screening or assessment. However, screening alone is only one part of the solution in the therapeutic process. Thus, a clear nutrition care pathway should indicate the action required based on the screening result. For this purpose, there is a wide variety of nutritional tools, which are available nowadays, but they should be reliable, validated, and easy [31]. MNA is one of the most common validated nutritional assessment tools used among the hospitalized elderly [36,37].

References

- Barker LA, Gout BS, Crowe TC (2011) Hospital malnutrition: prevalence, identification and impact on patients and the healthcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8(2): 514-527.

- Wu GH, Liu ZH, Wu ZH, Wu ZG (2006) Perioperative artificial nutrition in malnourished gastrointestinal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol 12(15): 2441-2444.

- Allard JP, Keller H, Jeejeebhoy KN, Laporte M, Duerksen DR, et al. (2016) Decline in nutritional status is associated with prolonged length of stay in hospitalized patients admitted for 7 days or more: a prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr 35(1): 144-152.

- Gout BS, Barker LA, Crowe TC (2009) Malnutrition identification, diagnosis and dietetic referrals: are we doing a good enough job? Nutr Diet 66(4): 206-211.

- Norman K, Pichard C, Lochs H, Pirlich M (2008) Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr 27(1): 5-15.

- Waitzberg DL, Caiaffa WT, Correia MI (2001) Hospital malnutrition: the Brazilian national survey (IBRANUTRI): a study of 4000 patients. Nutrition 17(7-8): 573-580.

- Adams NE, Bowie AJ, Simmance N, Murray M, Crowe TC (2008) Recognition by medical and nursing professionals of malnutrition and risk of malnutrition in elderly hospitalised patients. Nutr Diet 65(2): 144-150.

- Muscaritoli M, Anker SD, Argiles J, Aversa Z, Bauer JM, et al. (2010) Consensus definition of sarcopenia, cachexia and pre-cachexia: Joint document elaborated by Special Interest Groups (SIG) “cachexiaanorexia in chronic wasting diseases” and “nutrition in geriatrics” Clin. Nutr 29(2): 154-159.

- Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, Vellas B, Plauth M (2003) ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr 22(4): 415-421.

- Elia M, Zellipour L, Stratton RJ (2005) To screen or not to screen for adult malnutrition. Clin Nutr 24(6): 867-884.

- Pablo AR, Izaga MA, Alday LA (2003) Assessment of nutritional status on hospital admission: nutritional scores. Eur J Clin Nutr 57(7): 824-831.

- Green SM, Watson R (2005) Nutritional screening and assessment tools for use by nurses: literature review. J Adv Nurs 50(1): 69-83.

- Schiesser M, Muller S, Kirchhoff P, Breitenstein S, Schafer M, et al. (2008). Assessment of a novel screening score for nutritional risk in predicting complication in gastro-intestinal surgery. Clin Nutr 27(4): 565-570.

- Barker LA, Gout BS, Crowe TC (2011) Hospital malnutrition: prevalence, identification and impact on patients and the healthcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8(2): 514-527.

- DiMaria Ghalili RA (2002) Changes in nutritional status and postoperative outcomes in elderly CABG patients. Biol Res Nurs 4(2): 73-84.

- Baldwin C, Parson TJ (2004) Dietary advice and nutrition supplements in the management of illness-related malnutrition: a systematic review. Clin Nutr 23(6): 1267-1279.

- Chandra RK (1997) Nutrition and the immune system: an introduction. Am J Clin Nutr 66(2): 460S-463S.

- Hill GL (1992) Jonathan E. Rhoads Lecture. Body composition reserach: Implications for the practice of clinical nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 16(3): 197.

- Mechanick JI (2004) Practical aspects of nutrition support for wound healing patients. Am J Surg 188(1A Suppl): 52-56.

- Braunschweig C, Gomez S, Sheean PM (2000) Impact of declines in nutritional status on outcomes in adult patients hospitalized for more than 7 days. J Am Diet Assoc 100(11): 1316-1322.

- Gout BS, Barker LA, Crowe TC (2009) Malnutrition identification, diagnosis and dietetic referrals: Are we doing a good enough job? Nutr Diet 66(4): 206-211.

- Neumayer LA, Smout RJ, Horn HG, Horn SD (2001) Early and sufficient feeding reduces length of stay and charges in surgical patients. J Surg Res 95(1): 73-77.

- Anthony PS (2008) Nutrition screening tools for hospitalized patients. Nutr Clin Pract 23(4): 373-382.

- Vellas B, Villars H, Abellan G, Soto ME, Rolland Y, et al. (2006) Overview of the MNA® - Its History and Challenges. J Nutr Health Aging 10(6): 456-465.

- Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salva A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B (2001) Screening for Undernutrition in Geriatric Practice: Developing the Short-Form Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA-SF). J Geront 56(6): M366-377.

- Guigoz Y (2006) The Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA®) Review of the Literature - What does it tell us? J Nutr Health Aging 10(6): 466-487.

- Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, Uter W, Guigoz Y, et al. (2009) Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short-Form (MNA®-SF): A practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging 13(9): 782-788.

- Ghosh A, Dasgupta A, Paul B, Sembiah S, Biswas B, et al. (2017) Screening for Malnutrition among the Elderly with MNA Scale: A Clinic based Study in a Rural Area of West Bengal. Journal of Contemporary Medical Research 4(9): 1978-1982.

- Ranhoff AH, Gjoen AU, Mowe M (2005) Screening for malnutrition in elderly acute medical patients: the usefulness of MNA-SF. J Nutr Health Aging 9(4): 221-225.

- Durán Alert P, Milà Villarroel R, Formiga F, Virgili Casas N, Vilarasau Farré C (2012) Assessing risk screening methods of malnutrition in geriatric patients; Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) versus Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI). Nutricion hospitalaria 27(2): 590-598.

- Yaxley A, Crotty M, Miller M (2015) Identifying Malnutrition in an Elderly Ambulatory Rehabilitation Population: Agreement between Mini Nutritional Assessment and Validated Screening Tools. In Healthcare 3(3): 822-829.

- Jeliffe DB (1966) The assessment of nutritional status of the community. Geneva.

- Cereda E, Pusani C, Limonta D, Vanotti A (2009) The ability of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index to assess the nutritional status and predict the outcome of home-care resident elderly: a comparison with the Mini Nutritional Assessment. Br J Nutr 102(4): 563-570.

- Hengstermann S, Fischer A, Steinhagen Thiessen E, Schulz RJ (2007) Nutrition status and pressure ulcer: what we need for nutrition screening. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 31(4): 288-294.

- Cereda E, Pedrolli C (2009) The geriatric nutritional risk index. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 12(1): 1–7.

- DiMaria Ghalili RA (2014) Integrating nutrition in the comprehensive geriatric assessment. Nutr Clin Pract 29(4): 420-427.

- Stratton RJ, King CL, Stroud M, Jackson, Elia M (2006) “Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool” predicts mortality and length of hospital stay in acutely ill elderly. Brit J Nutr 95(2): 325-330.

- Harith S, Shahar S, Yusoff NAM, Kamaruzzaman SB, Hua PPJ (2010) The magnitude of malnutrition among hospitalized elderly patients in University Malaya Medical Centre. Health Environ J 1(2): 64-72.

- Sakinah H, Tan SL (2012) Validity of a local nutritional screening tool in hospitalized Malaysian elderly patients. Health Environ J 3(3): 59-65.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...