Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-5910

Short Communication(ISSN: 2638-5910)

Resistance Exercise Training and Diabetes Volume 3 - Issue 3

Francisco J F Saavedra1,2*

- 1Research Center for Sports Sciences, Health Sciences and Human Development, Portugal

- 2University of Trás-os-Montes & Alto Douro, Portugal

Received:April 27, 2021; Published: May 06, 2021

Corresponding author: Francisco Jose Felix Saavedra, Research Center for Sports Sciences, Health Sciences and Human Development, University of Trás-os-Montes & Alto Douro, Portugal

DOI: 10.32474/ADO.2021.03.000164

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the greatest today’s public health problems with enormous social and economic implications for society [1,2]. The implementation and maintenance of physical activity and exercise are critical for blood glucose controlling and general health in individuals with diabetes and prediabetes. Recommendations and precautions vary depending on individual characteristics and health status. Physical activity and exercise recommendations, therefore, should be tailored to meet the specific needs of each individual.

Why is exercise important? As well as strengthening the cardiovascular system and the body’s muscles, people exercise to keep fit, lose or maintain a healthy weight, improve their athletic skills, or only for pleasure. Recurrent and consistent physical exercise is recommended for people of all ages as it reinforces the immune system and helps protect against conditions such as: heart disease; stroke; type 2 diabetes; cancer and other major illnesses. Additional health benefits of exercising regularly include: improves mental health; increases self-esteem/confidence; boosts sleep quality and energy levels; cuts risk of stress and depression; defends against dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. In this point of view, we will briefly discuss some of the current and relevant literature and provide evidence-based practical recommendations for resistance exercise training in people with diabetes, according to international recommendations.

Resistance exercise training is the most effective method available for maintaining and increasing lean body mass and improving muscular strength and endurance. It is recommended as part of physical activity guidelines which includes working for all major muscle groups on two or more days a week. Diabetics can gain many health benefits from resistance training, such as increased muscle strength, increased muscle mass, and maintenance of bone density. Additionally, certain dimensions of health-related quality of life have been shown to improve in diabetics due to resistance training intervention. Resistance training is considered a significant element of a complete exercise program to complement the extensively recognised positive effects of aerobic training on health and physical abilities [3]. There is a robust indication that resistance training can moderate the effects of ageing on neuromuscular function and functional capacity [4-8]. Several forms of resistance training have the potential to increase muscle strength, mass, and power output [3]. Evidence reveals a dose-response association where volume and intensity are strongly related to adaptations to resistance exercise [8].

Specifically, adults should engage in muscle-strengthening activities of moderate to a high intensity which includes working for all major muscle groups on two or more days a week. For the aged adult, the same muscle-strengthening guidelines apply, as resistance training may hold even greater benefit for this population. Several health problems affecting older adults can be countered by adopting a regular resistance training program. For example, older adults are at greater risk of premature death due to falls, which is associated with age-related declines in muscular fitness and balance [8-12]. Older adults can gain other health benefits from resistance training, besides increased muscle mass and strength [13]. Studies have shown that resistance training can benefit bone mineral density [14,15], lipoprotein profiles [16], glycemic control [17], body composition [18], symptoms of frailty [19], metabolic syndrome risk factors [20] and cardiovascular disease markers [21]. An increasing amount of evidence suggests that resistance training plays a significant role in improving many health factors associated with the prevention of chronic diseases. Agreeing to the main international organizations, resistance training should be prescribed in combination with aerobic training because both types of exercise elicit distinct benefits, such as improvements in neuromuscular and cardiovascular functions [6], respectively, and both muscle strength and aerobic fitness are inversely associated with all-cause mortality in older individuals [3, 22-25].

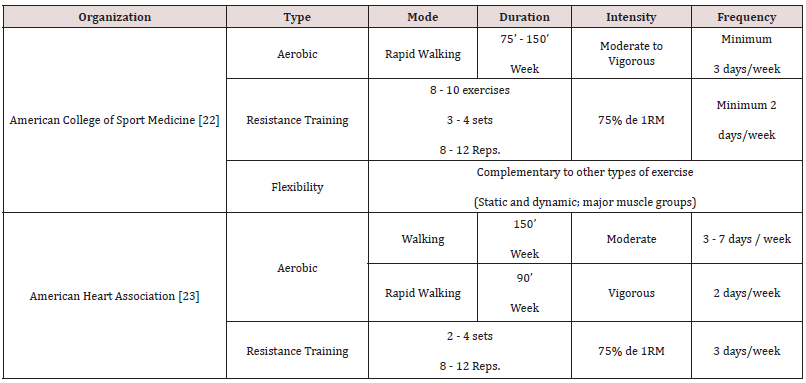

Although general recommendations are provided concerning special circumstances, in good practice, all resistance exercise programs should be adequate with the specific individual needs and competencies of each type of diabetes. Previously, should be carried out a thorough medical evaluation to rule out comorbidities and contraindications for physical exercise (myocardial infarction, or unstable angina, uncontrolled hypertension, acute heart failure and complete venous arterial blockage). It also must track the established plan and adequate monitoring of the potential side effects (muscle injury, joint and fractures). In short, the exercise prescription should be individualized (health status, chronic disease risk factors, behavioural characteristics, personal goals, and exercise preferences), progressive and with the same accuracy and precision that any pharmacological treatment [26,27]. Whereas an exercise prescription is a recommended physical activity program designed in a systematic and individualized manner in terms of the exercise Type; Mode; Duration; Intensity and Frequency. It should be planned according to the international exercise guidelines and recommendations and involved the combination of aerobic, resistance training, agility/balance and static and dynamic flexibility exercises in all sessions [26-28] (Table 1).

Table 1: International recommendations for the proper dose of exercise to a healthy adult.

RM: Repetition Maximum; Reps: Repetitions

To promote and maintain health, all healthy adults need to accumulate at least 150 minutes/week of aerobic exercise with moderate intensity (60-70% of maximum heart rate, or 12-13 in a subjectively perceived exertion range 6-20 points), distributed by most days of the week or to accumulate at least 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity (70% to 90% of the maximum heart rate, or 14 to 16, in a subjectively perceived exertion range from 6 to 20 points). Adults should still perform activities that maintain or increase muscular strength, at least two, non-consecutive, days per week. The elderly, in addition to the minimum levels of aerobic and resistance exercise recommended for adults, are advised to perform stretching exercises and balance at least 2 to 3 times/ week, to prevent falling and maintain and improve their autonomy and quality of life [3, 26-28]. Strength training should be performed 2 to 3 times a week, using 3 sets of repetitions 8-12, with an initial intensity of 20-30% of 1RM, progressing until 70% of 1RM. We can start strength training with resistance machines requesting major muscle groups (e.g. leg press and knee extension). However, exercises that involve monoarticular movements have a lower cardiovascular response (increased heart rate and blood pressure), being, at the beginning of the training process, more suitable to use in individuals with cardiovascular disease [27-29]. To optimize the improvement of the functional capacity, the strength training program should include strength exercises reproducing the daily living activity, for example, get up and sit [29].

Conclusion

In conclusion, physical activity and exercise is assumed as a fundamental part of the primary prevention of many chronic diseases, but also in delaying the progression and reducing the symptoms of its chronic conditions. Most of the benefits occur with at least 150 minutes of physical exercise of moderate intensity, accumulated over the week. It is recommended also vigorous aerobic exercise and strength exercises at least two days/week. Should be suggested and prescribed to all individual with diabetes as part of the management of glycemic control and overall health. Precise recommendations and precautions will vary by the type of diabetes, age, activity done, and presence of diabetes-related health complications. There are some exercise precautions which people with diabetes must take, however, when done safely, exercise is a valuable aid to optimal health (eaten too little carbohydrate [fruit, milk, starch] relative to the exercise.; taken too much medication relative to the exercise; the combined effect of food and medication imbalances relative to the exercise). Recommendations should be tailored to meet the specific needs of each individual. Also, physical activity and exercise should be adapted to the characteristics and contraindications of each individual, as well as, should be prescribed with a progressive individualized plan, to have continued benefits, just like other medical treatments..

References

- World Health Organization (2014) Global Status Report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- T Seuring, O Archangelidi, M Suhrcke (2015) The Economic Costs of Type 2 Diabetes: A Global Systematic Review. PharmacoEconomics 33(8): 811:831

- Fragala MS, Cadore EL, Dorgo S, Izquierdo M, Kraemer WJ, et al. (2019) Resistance Training for Older Adults: Position Statement From the National Strength and Conditioning Association. J Strength Cond Res 33(8): 2019-2052.

- Borde R, Hortobágyi T, Granacher U (2015) Dose-Response Relationships of Resistance Training in Healthy Old Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med 45(12): 1693-1720.

- Cadore EL, Casas Herrero A, Zambom Ferraresi F, Idoate F, Millor N, et al. (2014) Multicomponent exercises including muscle power training enhance muscle mass, power output, and functional outcomes in institutionalized frail nonagenarians. Age (Dordr) 36(2): 773-785.

- Cadore EL, Izquierdo M, Pinto SS, Alberton CL, Pinto RS, et al. (2013) Neuromuscular adaptations to concurrent training in the elderly: Effects of intrasession exercise sequence. Age (Dordr) 35(3): 891-803.

- Silva RB, Eslick GD, Duque G (2013) Exercise for falls and fracture prevention in long term care facilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14(9): 685-689.

- Steib S, Schoene D, Pfeifer K (2010) Dose-response relationship of resistance training in older adults: A meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42(5): 902-914.

- Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER (2016) Falls and Fall Injuries Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years - the United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65(37): 993-998.

- Ahmadiahangar A, Javadian Y, Babaei M, Heidari B, Hosseini SR, et al. (2018) The role of quadriceps muscle strength in the development of falls in the elderly people, a cross-sectional study. Chiropr Man Therap 26(1): 1-6.

- Van Ancum JM, Pijnappels M, Jonkman NH, Scheerman K, Verlaan S, et al. (2018) Muscle mass and muscle strength are associated with pre-and post-hospitalization falls in older male inpatients: A longitudinal cohort study. BMC Geriatr 18(1): 116.

- Skinner EH, Dinh T, Hewitt M, Piper R, Thwaites C (2016) An Ai Chi-based aquatic group improves balance and reduces falls in community-dwelling adults: A pilot observational cohort study. Physiother Theory Pract 32(8): 581-590.

- Westcott WL (2012) Resistance training is medicine: effects of strength training on health. Curr Sports Med Rep 11(4): 209-216.

- Huovinen V, Ivaska KK, Kiviranta R, Bucci M, Lipponen H, et al. (2016) Bone mineral density is increased after a 16-week resistance training intervention in elderly women with decreased muscle strength. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016; 175(6):571-82.

- Anek A, Kanungsukasem V, Bunyaratavej N (2015) Effects of aerobic step combined with resistance training on biochemical bone markers, health-related physical fitness and balance in working women. J Med Assoc Thai 98(8):42-51.

- Ribeiro AS, Tomeleri CM, Souza MF, Pina FL, Schoenfeld BJ, et al. (2015) Effect of resistance training on C-reactive protein, blood glucose and lipid profile in older women with differing levels of RT experience. Age (Dordr) 37(6): 109.

- Takenami E, Iwamoto S, Shiraishi N, Kato A, Watanabe Y, et al. (2019) Effects of low-intensity resistance training on muscular function and glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig 10(2): 331-338.

- Cavalcante EF, Ribeiro AS, do Nascimento MA, Silva AM, Tomeleri CM, et al. (2018) Effects of Different Resistance Training Frequencies on Fat in Overweight/Obese Older Women. Int J Sports Med 39(7): 527-534.

- Nagai K, Miyamato T, Okamae A, Tamaki A, Fujioka H, et al. (2018) Physical activity combined with resistance training reduces symptoms of frailty in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 76: 41-47.

- Tomeleri CM, Souza MF, Burini RC, Cavaglieri CR, Ribeiro AS, et al. (2018) Resistance training reduces metabolic syndrome and inflammatory markers in older women: A randomized controlled trial. J Diabetes 10(4): 328-337.

- Shaw BS, Gouveia M, McIntyre S, Shaw I. Anthropometric and cardiovascular responses to hypertrophic resistance training in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016; 23(11):1176-81.

- Pescatello LS (2017) ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 10th Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health.

- Riegel B, Moser DK, Buck HG, Dickson VV, Dunbar SB, et al. (2017) Self-Care for the Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association. J Am Heart Assoc 6(9): 006997.

- American College of Sports Medicine (2009) American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41(3): 687-708.

- Haff G, Triplett NT (2016) Essentials of strength training and conditioning. 4th Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. pp. 462.

- Cadore EL, Rodríguez Mañas L, Sinclair A, Izquierdo M (2013) Effects of different exercise interventions on risk of falls, gait ability, and balance in physically frail older adults: A systematic review. Rejuvenation Res 16(2): 105-114.

- Cadore EL, Izquierdo M (2013) How to simultaneously optimize muscle strength, power, functional capacity, and cardiovascular gains in the elderly: An update. Age (Dordr) 35(6): 2329-2344.

- Izquierdo M, Häkkinen K, Ibañez J, Garrues M, Antón A, et al. (2001) Effects of strength training on muscle power and serum hormonesin middle age and older men. J Appl Phys-iol 90(4): 1497-1507.

- Casas Herrero A, Cadore EL, Martinez Velilla N, Izquierdo Redin M (2015) Physical exercise in the frail elderly: An update. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 50(2): 74-81.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...