Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-5910

Research Article(ISSN: 2638-5910)

Effectiveness, Safety and Therapeutic Adherence of Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide for Weight Management in Real Practice: An Observational Study Volume 3 - Issue 2

Santiago Tofé 1,2*, Iñaki Argüelles1,2, Guillermo Serra1, Mayte Izco3 and Juan Ramón Urgelés1

- 1Department of Endocrinology and Nutrition. University Hospital Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca, Spain

- 2Clínica Juaneda and Policlínica Miramar, Juaneda Hospitals Group, Palma de Mallorca, Spain

- 3Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Received:April 05, 2021; Published: April 14, 2021

Corresponding author: Santiago Tofé, Department of Endocrinology and Nutrition, University Hospital Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca, Spain

DOI: 10.32474/ADO.2021.03.000161

Abstract

Aims: To evaluate in a real practice setting effectiveness, safety and adherence to weekly subcutaneous semaglutide for weight

reduction, along with diet and lifestyle modifications in obese/overweighted patients attending an Obesity Unit.

Materials and Methods: In a retrospective study, 367 patients (mean age 50.25 years, 78.36% female, mean baseline body

mass index 32.39 kg/m2) were followed for 10.7 months (median) after initiation of semaglutide. Up to 24.25% of patients were

previously on GLP-1 analogue therapy (mostly liraglutide) and 36.26% used background oral medication for weight loss.

Results: At final office visit patients averaged a weight loss of 7.97±3.42 kg (9.13±3.86% baseline body weight) and 88.07%

and 30.27% of patients had achieved a≥5% and ≥10% weight loss, respectively, as compared to baseline body weight. Up to 61.19%

and 33.46% of patients maintained 0.5 and 1.0 mg dose, respectively and 86.18% of patients persisted on sc semaglutide by last

office visit. Nausea and abdominal pain were reported by 12.53% of patients with no severe adverse events. Background antiobesity

medication did not affect weight loss and patients on previous GLP-1 analogue therapy lost 1.43 kg less than naïve patients

(p<0.001).

Conclusions: Out-of-label weekly administration of sc semaglutide 0.5 to 1.0 mg resulted in a significant, safe and affordable

weight loss in a pragmatic setting without reimbursement of treatment cost. Magnitude of weight loss and safety profile was in line

with preliminary data from a phase 2 trial, although this will need to be confirmed by an ongoing phase 3 development programme.

Keywords: Observational Study; Obesity Therapy; GLP-1 Analogue; Semaglutide; Appetite Control Antiobesity Drug

Introduction

Obesity has become a major public health issue worldwide,

and its prevalence is growing so uncontrolled that over the past

20 years, the rate of obesity has risen three-fold and is affecting

more than 30% of population in some European countries [1].

Major health institutions recognize now obesity as a complex,

multifactorial condition [2,3], associated to a number of

comorbidities, including metabolic, mechanical and mental health

complications that significantly impact both quality of life [4,5]

and life expectancy of affected population [6]. On the other side,

treatment cost of complications derived from obesity represents

a formidable burden for health public systems in many countries

[7,8]. Conversely, a weight loss of 5-10% of body mass reduces

obesity-related complications and improves quality of life [9,10],

although this goal is difficult to achieve and maintain only with

diet and lifestyle interventions [11,12]. Few safe and effective

drugs are currently available for the treatment of obesity. Among them, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists have

proven a combined effect on glucose metabolism and reduction in

body weight associated to favourable outcomes in patients with

type 2 Diabetes and coexisting obesity, including reduction of

cardiovascular events for some of them [13-15].

Liraglutide, a once daily administered GLP-1 analogue was

initially approved for treatment of patients with type 2 Diabetes

at a dose of 1.2 to 1.8 mg, and subsequently gained approval for

weight reduction in many countries, at a maximum daily dose of 3.0

mg, in combination with diet and lifestyle modifications [16-17].

Subcutaneous (sc) semaglutide, a longer-acting GLP-1 analogue

was approved in Spain in 2019 for treatment of type 2 Diabetes

with a weekly administration of 0.5 or 1.0 mg, and conditions

for reimbursement by Spanish public health system include

coexistence of obesity. Both drugs have proven clinically significant

weight reductions in obese patients without type 2 Diabetes and

a clinical development program is currently undergoing aiming to

gain indication for sc semaglutide in weight management [18-19].

In this observational retrospective study, performed under real

practice conditions, we aimed to evaluate effectiveness, safety and

adherence to weekly administration of sc semaglutide in a nonreimbursed

setting in patients with obesity or overweight attending

an Obesity Unit in a private institution in Mallorca (Spain), along

with dietary and lifestyle recommendations.

Patients and Methods

In this retrospective study, patients attending our Obesity Unit

who started on sc semaglutide since May 2019 were consecutively

invited to take part in the study and after giving written informed

consent, were included for analysis. Inclusion criteria were patients

18-year-old or older, with a body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2, and

at least one follow-up office visit after initiation of sc semaglutide.

A total of four follow-up visits after baseline visit were included

in this study, to ensure for at least a 6-month follow-up period.

Patients with a previous diagnosis of type 2 Diabetes Mellitus were

excluded from participation in this study. The study protocol was

approved by the reference Hospital Ethics Committee (University

Hospital Son Espases).

A total of 372 patients were consecutively included in the study.

All patients were prescribed sc semaglutide with an out-of-label

indication for weight reduction, as part of a structured program for

the management of overweight and/or obesity that included diet

and exercise counselling. A number of patients had been previously

or currently prescribed drugs with an approved indication for

weight management (GLP-1 analogue liraglutide and lipase

inhibitor orlistat) or a clinical indication for weight management yet

out of label, as other GLP-1 analogues (dulaglutide, exenatide LAR),

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), and topiramate.

Diet counselling included a structured quantitative dietary

recommendation with an average 500 kcal/day reduction from

calculated baseline metabolic rate. Standardized Harris-Benedict’s

equations corrected for Lang’s daily activity coefficient were used

to calculate baseline metabolic rate. In line with Spanish Health

Authorities policy, sc semaglutide prescription for overweight or

obesity management is not reimbursed, and all patients paid for

this out-of-pocket prescription accordingly.

Height, weight, and BMI were recorded as baseline variables at

initial visit. Also, concomitant use of drugs with a potential to reduce

weight including topiramate, orlistat, SSRIs and current or previous

use of other GLP-1 analogues in the last 6 months previous to index

date was also registered. At initial visit, sc semaglutide was started

at a dose of 0.25 mg once weekly according to label instructions,

but subsequent dose titration was left to physician’s judgement

based upon effectiveness and Gastrointestinal (GI) intolerance

(namely, incidence of nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain). Patients

in this unit are regularly followed-up with office visits every 4-12

weeks, and weight, current sc semaglutide dose, use of background

medications for weight loss, incidence of adverse events and

persistence on sc semaglutide were systematically recorded at each

visit and included for analysis. Safety data included serious adverse

events, incidence of GI intolerance and incidence of other adverse

events.

Primary effectiveness outcome in this study was absolute

and percentage weight loss from baseline after initiation of

sc semaglutide until last follow-up visit. Secondary objectives

included persistence on sc semaglutide and drug dose, evaluated

at each follow-up visit, incidence of non-serious/serious adverse

events and/or GI adverse events, proactively requested to patients,

and change in background use of drugs for weight loss. Subgroup

analysis evaluated influence of previous GLP-1 analogues therapy

and background use of anti-obesity drugs in weight loss.

Statistical Analysis

Primary and secondary outcomes analysis was performed for patients attending the last office visit. Subgroup analysis for previous use of GLP-1 analogues and use of anti-obesity medication included all patients with at least one follow-up office visit (last observation carried forward). All data are expressed as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as percentage for categorical variables. Normally distributed variables were compared using two-sided T-Student test and categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test. A p value <0.05 was assumed as statistically significant for all comparisons (Statplus statistical package 2016©, AnalystSoft, Walnut, CA).

Results

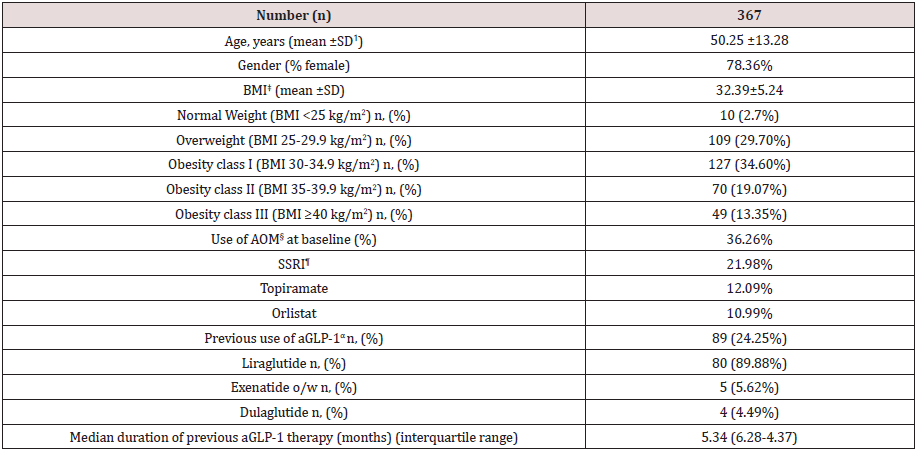

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of patients included in this study. A total of 367 patients completed a first follow-up visit. On average, patients had a mean age of 50.25 years and a wide majority of them were females (78.36%). Mean BMI was 32.39±5.24 kg/ m2, with a balanced distribution among patients with overweight (29.7%), class I obesity (37.32%) class II and III obesity (together, 32.42%). Up to 36.26% patients were on previous pharmacological treatment for obesity, mostly SSRI agents, topiramate and orlistat, and up to 24.25% of this population initiated sc semaglutide switching from a previous GLP-1 analogue therapy, either currently in use or in the previous 6 months. In most cases (89.88%) previous GLP-1 analogue was liraglutide with an average daily dose of 1.48 mg. Median duration of previous aGLP-1 therapy was 5.34 months and mean (±SD) weight reduction achieved was 3.25 ±5.32 Kg (Table 2). Up to 32.01% of patients in this subgroup had achieved a ≥5% weight loss with previous aGLP-1 therapy.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of patients.

ꝉSD: Standard Deviation ‡BMI: Body Mass Index §AOM: Anti-obesity Medication ¶SSRI: Selective Serotonine Re-uptake Inhibitor αaGLP-1: Glucagon-like Peptide 1 against.

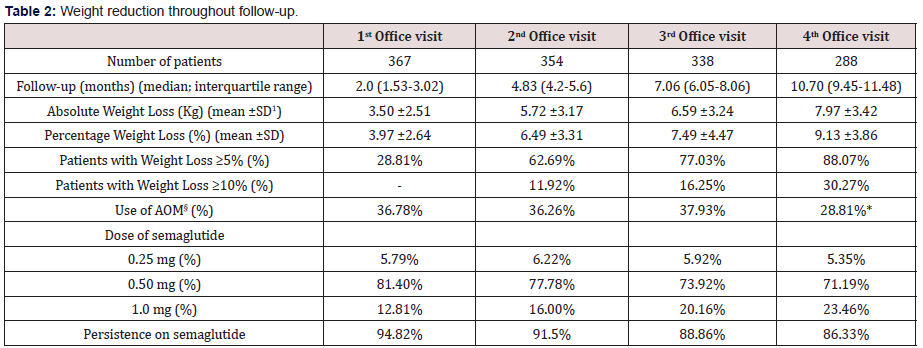

Table 2: Weight reduction throughout follow-up.

ꝉSD: Standard Deviation §AOM: Anti-obesity Medication *p<0.05 vs. baseline (Chi-square test)

Weight Reduction

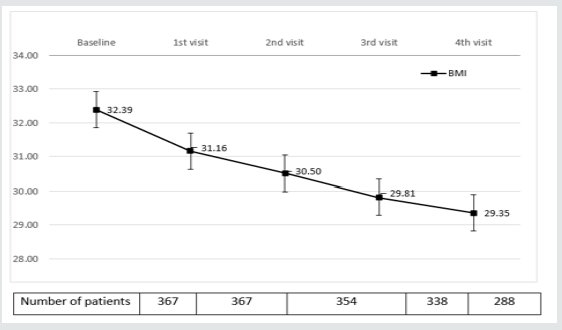

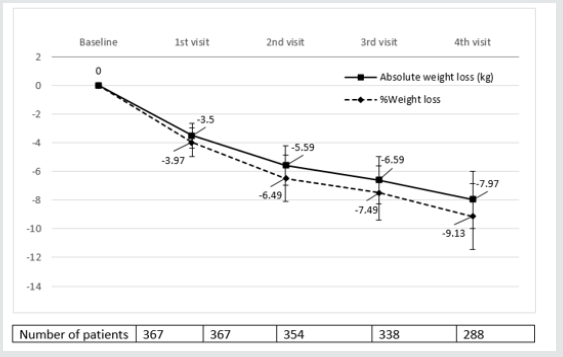

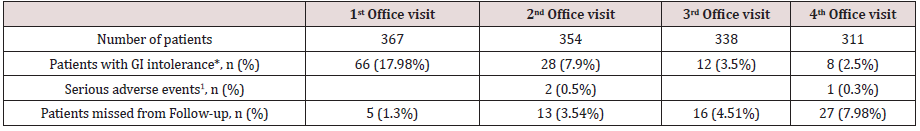

Table 3 and (Figures 1&2) show changes in BMI and body weight throughout consecutive office visits. After a median followup of 10.7 months up to 311 patients attending the last office visit, achieved a weight loss of 7.97±3.42 kg (9.13±3.86% of baseline body weight), and weight loss was achieved gradually in a timedependent fashion. By the end of study observation period, 88.07% and 30.27% of patients had achieved a ≥5% and ≥10% weight loss, respectively, as compared to baseline body weight.

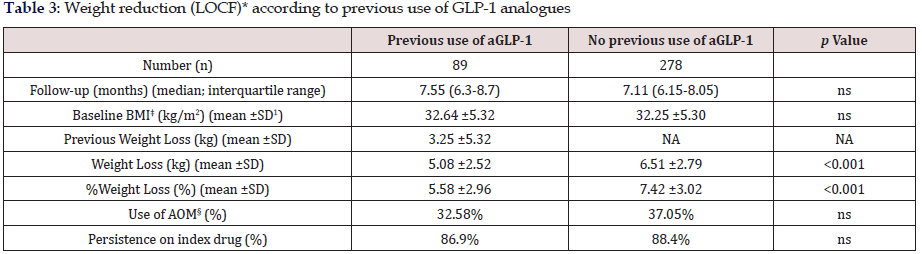

Table 3: Weight reduction (LOCF)* according to previous use of GLP-1 analogues

*LOCF: Last observation carried forward ꝉSD: Standard Deviation ‡BMI: Body Mass Index §AOM: Anti-obesity Medication

Figure 1: Evolution of BMIα after initiation of sc Semaglutide*. αBMI: Body mass index expressed in Kg/m2 *Expressed as median values. Bars represent ± standard deviation.

Figure 2: Absolute and Percentage weight loss after initiation of sc semaglutide*. *Expressed as median values. Bars represent ± standard deviation.

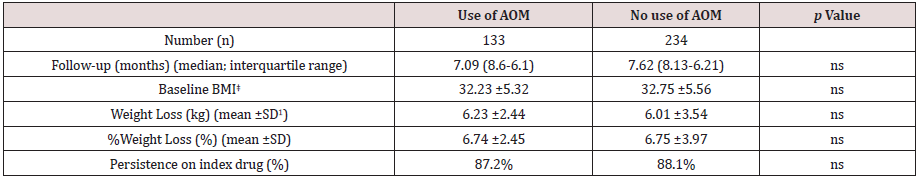

Tables 3 and 4 show changes in body weight according to previous use of GLP-1 analogue therapy and concomitant use of anti-obesity drugs, respectively. As stated before, up to 24.25% patients had switched to sc semaglutide from treatment with a GLP-1 analogue in the previous six months, mostly liraglutide. This subgroup of patients had achieved a previous weight reduction of 3.25 ±5.32 Kg after a median follow-up of 5.34 months (interquartile range, 4.12-6.57 months). Patients without previous use of a GLP-1 analogue, reduced significantly more weight than patients switching from a previous GLP-1 analogue to sc semaglutide, after a similar follow-up period (last observation carried forward); 6.51±2.79 kg (7.42% of baseline body weight) vs. 5.08±2.52 kg (5.58%), respectively (p<0.001). No differences were found for concomitant use of other anti-obesity medications and persistence on sc semaglutide was quite similar between both groups (Table 3). Conversely, sub analysis of weight reduction according to concomitant use of any anti-obesity medication did not yield any significant differences between both subgroups, neither in baseline BMI, nor in the magnitude of weight loss (last observation carried forward), or in the persistence on sc semaglutide (Table 4).

Table 4: Weight reduction (LOCF)* according to previous use of anti-obesity medication

*LOCF: Last observation carried forward ꝉSD: Standard Deviation ‡BMI: Body Mass Index

Table 5: Safety and tolerability of sc semaglutide

*GI (Gastrointestinal) intolerance included nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or diarrhoea. ꝉOne patient admitted to hospital for urinary sepsis, one patient diagnosed of gross bowel cancer and one patient with myocardial infarction.

Therapeutic Persistence, Drug Dose and Background Anti-Obesity Medication Use

A total of 311 patients did attend the fourth and last office visit included in this study (84.74%). Persistence on sc semaglutide was high throughout consecutive office visits, with up to 268 patients out of 311 (86.18%) attending the last office visit being persistent to the drug. Up to 61.19% of patients remained on an initially prescribed semaglutide dose of 0.5 mg (after initial up titration) throughout consecutive office visits and 33.46% of patients were on the 1.0 mg dose by the last office visit. Concomitant use of other anti-obesity drugs remained unchanged throughout follow-up visits, and only in the last office visit a statistically significant 7.45% reduction in use of other agents was detected, mostly affecting orlistat use.

Safety and Tolerability

Regarding safety, few severe adverse events were reported throughout the follow-up period. A 66 year-old female was admitted to hospital due to urinary sepsis, a morbid obese 54 year-old male patient was diagnosed of gross bowel cancer requiring surgery and a 61 year-old patient suffered a non-lethal myocardial infarction. Additionally, a patient accidentally administered 5 consecutive daily doses of 0.25 mg of sc semaglutide and reported on nausea and vomiting during two days, but her condition improved after stopping the medication, and after two weeks, the patient resumed correctly weekly administration of sc semaglutide. A total of 66 patients (17.98%) complained on GI symptoms at initial follow-up visit, and this percentage did reduce significantly in subsequent follow-up visits (Table 5). Most of these patients complained of nausea and abdominal pain, that in some cases deserved transient interruption of medication or use of omeprazole, and in 14 patients led to definitive interruption of medication. Other reasons for treatment abandonment included lack of effectiveness or inability to afford for treatment costs, as reported by up to 19 patients. A patient with a baseline BMI of 42.3 kg/m2 was derived to bariatric surgery after 3 months of sc semaglutide 1.0 mg, with a weight loss of 5.3 kg from baseline.

Discussion

In this observational study we evaluated weight reduction associated to out-of-label use of sc semaglutide in a patient population with overweight or obesity as part of a pragmatic strategy for weight management including diet and physical activity counselling, and in selected cases prescription of drugs with a potential for weight loss. Patients included in this study represent an average profile of patients typically attending an obesity clinic in a private setting; middle aged patients with a high proportion of women and an average baseline BMI >30 kg/m2. Conversely, we found a lower percentage of patients with morbid obesity, as compared to Spanish public health system obesity units, were most patients are morbid obese and referred to for consideration of bariatric surgery [20]. A substantial proportion of patients included in this study were previously on pharmacological therapy for weight loss. In Spain, according to the 2016 official position statement by the Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity (SEEDO) [21], only lipase inhibitor orlistat, combination of opioid receptor antagonist/antidepressant naltrexone/bupropion and GLP-1 agonist liraglutide are approved drugs for medium and longterm obesity management in patients with a BMI >30 kg/m2 or >27 kg/m2 with major comorbidities, when a structured program including diet and lifestyle changes fails to promote a weight loss >5% after 3 to 6 months of follow-up. Conversely, the 2016 clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity issued by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) [22] include lorcaserin, phentermine/topiramate ER (extended release) combination and SSRI therapy for selected patients as medications for chronic weight management.

Taking in mind the strong correlation between obesity and depressive mood disorder [23,24], it is not surprising that up to 21.98% of our patients were on SSRI (mostly fluoxetine) and in some cases with a coexisting indication for binge eating disorder or night eating syndrome. Eighty-nine patients in this study were using or had used in the past six months a GLP-1 analogue for weight reduction. Liraglutide was by far the most frequently used drug with an average daily dose of 1.48 mg which is lower than the approved dose of 3.0 mg od for weight reduction. Lack of reimbursement by Spanish public health system for liraglutide in obese subjects plays probably an important role in this low average dose used by patients, as treatment cost is directly dose-dependent. This issue has been acknowledged as a mayor limitation for treatment accessibility in our country, as stated by SEEDO guidelines [21]. Nevertheless, despite this low dose, patients on liraglutide achieved an average weight loss of 3.25 kg, accounting for >3% of baseline weight, after a median period of 5.34 months. Interestingly, the clinical development program for liraglutide LEAD (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes) included 4,456 patients with type 2 Diabetes with an average baseline BMI of 31.83 kg/m2, and age 55.87 years old. Weight loss associated to liraglutide 1.2 and 1.8 mg ranged 2.3 to 2.8 kg, respectively, after 26 to 52 weeks [25-30]. A similar baseline BMI in an older population was associated to a lower weight loss as compared to patients in our study. A possible explanation for this could be differences in age, as Mezquita et al., demonstrated in their liraglutide survey Diabetes Monitor [31]. In this real-world web-based survey, patients with type 2 Diabetes under 50 years old lost significantly more weight as compared to patients over 60 years old. Nevertheless, potential differences in the response to GLP-1 analogues in a population without Diabetes cannot be excluded, as clear differences in GLP-1 biology in patients with type 2 Diabetes as compared to normal individuals have been detected [33], namely reduction of GLP-1 secretion in response to oral intake and reduction of insulinotropic potency of GLP-1 [34,35].

Patients in our study gradually achieved a clinically significant weight loss of 7.97 kg by the last office visit, accounting for 9.13% of initial body weight, after a median follow-up of 10.7 months. By the end of the study, 88.07% and 30.27% of patients attending the last office visit included in the observation period had achieved a ≥5% and ≥10% weight loss, respectively. According to SEEDO guidelines [21], a sustained weight loss of 3-5% of body weight is associated to clinically significant improvements in metabolic factors like blood glucose and plasma lipid concentrations, and reduces risk for development of Diabetes, with higher weight loss having the potential to reduce long-term cardiovascular complications. Conversely, AACE/ACE guidelines for obesity management recommend a weight-loss goal of 5-10% (≥15% in some circumstances) to induce improvements of comorbidities associated to overweight or obesity [22].

Interestingly, most patients included in the study remained in the 0.5 mg ow dose, and only 33.46% of patients increased to the 1.0 mg ow dose at any office visit. Again, rather than GI intolerance or perceived effectiveness, we believe that economic constraints play a major role in the capability of patients to afford for higher doses of sc semaglutide. Throughout follow-up, use of other medications with a potential to reduce weight did not experience a substantial change except for last office visit, in which a 7.45% reduction was observed, affecting mostly to orlistat use. A reduction in meal size and fat content to avoid nausea, which is a common advice given to patients on GLP-1 analogues [17,36] could explain this observed reduction in orlistat use.

Persistence on sc semaglutide was high throughout study observation period, with more than 86.33% of patients using the drug by the last office visit after a median of 10.70 months. This persistence is comparable to that observed in a recent publication by our group [37] in patients with type 2 Diabetes in a real-world setting using sc semaglutide under approved indication for glucose management, with a full reimbursement by public health system. As opposed to patients in our study, with an out-of-pocket indication for weight loss, this high persistence is reflecting in our opinion, a high degree of patient’s perceived effectiveness of sc semaglutide for weight reduction. Patients’ satisfaction was not specifically measured in this study but indeed a perception of successful weight management was frequently referred by patients to treating physicians. Additionally, a low percentage of patients complained of GI intolerance, mostly nausea and abdominal pain, and in most cases, these symptoms were mild to moderate in intensity and transient, thus allowing for treatment continuation. Up to 19 patients attending office visits declared inability to afford for treatment cost, despite good tolerance and significant weight loss. Few serious adverse events were seen in this study, none of them with a potential direct relationship to the use of sc semaglutide. Furthermore, overall persistence on sc semaglutide in this study was higher than that reported for other GLP-1 analogues in patients with type 2 diabetes in other real-world setting studies [38,39].

In 2010, Astrup and colleagues published the results of a trial evaluating for the first time, efficacy and tolerability of liraglutide in adult obese patients without diabetes [16]. Patients randomized to 1.2 to 3.0 mg of liraglutide lost 4.8 to 7.2 kg compared with 2.8 kg with placebo after a 20-week follow-up period, setting the evidence for use of liraglutide in obesity. These results represent a deeper weight reduction in obese patients without diabetes, as compared to patients with type 2 diabetes in the LEAD program, and are closer to those observed in the subgroup of patients with a previous treatment with liraglutide in our observational study, despite differences in study design and observation period.

In 2018, O’Neil et al. published the results of a phase 2 trial evaluating efficacy and safety of daily sc semaglutide compared to liraglutide and placebo in 957 obese individuals with a baseline BMI of 39.3 kg/m2 and age 47 years-old [18]. Patients randomized to 0.05 to 0.4 mg of sc semaglutide od lost -6·0% (0·05 mg), -8·6% (0·1 mg), -11·6% (0·2 mg), -11·2% (0·3 mg), and -13·8% (0·4 mg) as compared to -7.8% of initial body weight in patients randomized to liraglutide 3.0 mg od, throughout 52 weeks of treatment. In this study, proportion of patients with ≥5% and ≥10% weight loss vs baseline body weight ranged 54-90% and 19-72%, respectively, across different sc semaglutide doses. In our study, calculated average weekly sc semaglutide dose was 0.59 mg, which results in an estimated daily dose of 0.084 mg, close to the 0.1 mg od dose arm in the study by O’Neil et al., and with similar results in terms of weight loss (9.13% vs 8.6%) and proportion of patients with ≥5% and ≥10% weight loss (88% and 30% vs 67% and 37%, respectively). All sc semaglutide doses were generally well tolerated, with no new safety concerns. The most common adverse events were dose-related gastrointestinal symptoms, primarily nausea, as seen previously with GLP-1 agonists in patients with type 2 Diabetes and rarely led to discontinuation of treatment. No patient complained on symptoms suggesting hypoglycaemic episodes, reassuring the safe use of the drug in a population with normal glucose metabolism. A comprehensive clinical development program, the Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with Obesity (STEP) program is now undergoing, aiming to investigate the effect of sc semaglutide on weight loss, safety, and tolerability in adults with obesity or overweight. The program comprises 5 randomized clinical trials for which results will be available through 2020- 2021[19]. For all trials, the primary end point is change from baseline to end of treatment in body weight. Participants have a mean age of 46.2 to 55.3 years, are mostly female (mean 74.1%- 81.0%), and have a mean BMI of 35.7 to 38.5 kg/m2.

Our study represents the first published evidence for effectiveness and safety of sc semaglutide with a weekly administration in the management of overweight and obesity in adults without diabetes in a real-world setting. An important point in this study, derived from its observational nature in real practice conditions, is that patients paid for sc semaglutide treatment and still a high percentage of them remained persistent to the therapy. Treatment adherence is one of the major drivers for the gap between efficacy observed in clinical trials and effectiveness found in real practice in chronic conditions like type 2 Diabetes [40], and obesity shares similarities with it, both in their chronic nature and in their pathophysiology. Weight reduction is a strong signal for patients’ perception of effectiveness that reinforces treatment adherence and this is probably one of the reasons for the high treatment adherence found in our study. Undoubtedly, treatment cost and treatment adherence will significantly impact effectiveness of antiobesity drugs in future real-world studies.

Our study has several limitations derived from its real-world descriptive nature. First, the lack of a control group does not allow to assign achieved weight loss to the solely effect of sc semaglutide, although previous evidence from randomized trials shows a similar degree of weight loss associated to the drug. Second, a number of patients were missed from follow-up for weight evolution, so again a selection bias overestimating treatment effect cannot be excluded, being this is a typical limitation of real-world studies. Third, a number of patients were included in this study with current use of other drugs with a potential for weight loss, both oral medications and GLP-1 analogues, so a potential confounding effect of these treatments cannot be completely excluded. Nevertheless, we performed a subgroup analysis where oral anti-obesity medications were not found to impact significantly on weight reduction and conversely, previous use of GLP-1 analogues was associated to a significantly lower weight loss, assuming that part of the potential for weight reduction associated to GLP-1 agonist therapy had already been achieved in those patients. Finally, it is not usual that an observational study reporting on effectiveness and safety of a drug in real practice conditions is published before gaining regulatory approval for the specific indication, as efficacy and mostly safety are important issues that must be first addressed by randomized clinical trials, and the authors deeply acknowledge this fact. Nevertheless, several important questions must be kept in mind in this regard; first, sc semaglutide has been approved by regulatory agencies in most developed countries for use in patients with type 2 diabetes and conditions for reimbursement in Spain include coexisting obesity, which virtually affects most patients with type 2 Diabetes. Second, liraglutide, a GLP-1 analogue with a similar molecular design and pharmacological properties has been approved for weight reduction in patients with obesity and third, given the shortage of effective treatments to treat obesity and the barriers that treatment cost may represent for patients’ accessibility to such therapies, the authors believe that evidence provided by this study is timely, and of scientific interest.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in this observational study in real practice conditions, we have demonstrated that sc semaglutide at a weekly dose of 0.5 to 1.0 mg administered to patients with overweight or obesity in the pragmatic context of a structured program along with diet and lifestyle recommendations resulted in a sustained, safe and affordable clinically significant weight reduction. Given the limitations of a retrospective observational study, we will need to confirm these results with the forthcoming results of the STEP program and contrast them with results from other groups in a real practice setting which for sure will be coming up in future. Until then, we consider that weekly sc semaglutide represents a useful tool for helping patients in their long-term struggle, along with diet and lifestyle changes, to increase their chances to arrive to and maintain a healthy body weight.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to deeply thank to all patients for their participation in the study.

References

- Berghofer A, Pischon T, Reinhold T, Apovian CM, Sharma AM, et al. (2008) Obesity prevalence from a European perspective: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 8: 200.

- James PT, Rigby N, Leach R, International Obesity Task Force (2004) The obesity epidemic, metabolic syndrome and future prevention strategies. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 11(1): 3-8.

- York DA, Rossner S, Caterson I, et al. (2004) Prevention conference VII: Obesity, a worldwide epidemic related to heart disease and stroke: Group I: Worldwide demographics of obesity. Circulation 110(18): 463-470.

- Kaukua J, Pekkarinen T, Sane T, Mustajoki P (2003) Health-related quality of life in obese outpatients losing weight with very-low-energy diet and behaviour modifi cation: A 2-y follow-up study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27(9): 1072-1080.

- Hassan MK, Joshi AV, Madhavan SS, Amonkar MM (2003) Obesity and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional analysis of the US population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27(10): 1227-1232.

- Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, De Block CE (2006) Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature 444(7121): 875-880.

- Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C (2012) The medical care costs of obesity: An instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ 31(1): 219-230.

- World Obesity Federation. World obesity day 2017: Global data on costs of consequences.

- Mertens IL, Van Gaal LF (2000) Overweight, obesity, and blood pressure: The effects of modest weight reduction. Obes Res 8(3): 270-278.

- Warkentin LM, Das D, Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Padwal RS (2014) The effect of weight loss on health-related quality of life: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes Rev 15(3): 169-182.

- Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, Lew AM, Samuels B, et al. (2007) Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. Am Psychol 62(3): 220-233.

- Dombrowski SU, Knittle K, Avenell A, Araujo-Soares V, Sniehotta FF (2014) Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 348: 2646.

- Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, et al. (2016) Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 375(4): 311-22.

- Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, Eliaschewitz FG, Jódar E, et al. (2016) Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 376(9): 890.

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, et al. (2019) Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): A double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 394(10193): 121-130.

- Astrup A, Rössner S, Van Gaal L, Rissanen A, Niskanen L, et al. (2009) Effects of liraglutide in the treatment of obesity: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet 374(9701):1606-1616.

- Novo Nordisk (2014) Inc. Liraglutide 3.0 mg for weight management. NDA 206-321

- O'Neil PM, Birkenfeld AL, McGowan B, Mosenzon O, Pedersen SD, et al. (2018) Efficacy and safety of semaglutide compared with liraglutide and placebo for weight loss in patients with obesity: A randomised, double-blind, placebo and active controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 trial. Lancet 392(10148): 637-649

- Kushner RF, Calanna S, Davies M, Dicker D, Garvey WT, et al. (2020) Semaglutide 2.4 mg for the Treatment of Obesity: Key Elements of the STEP Trials 1 to 5. Obesity (Silver Spring) 28(6): 1050-1061.

- Basterra-Gortari FJ, Beunza JJ, Bes-Rastrollo M, Toledo E, García López M, et al. (2011) Increasing trend in the prevalence of morbid obesity in Spain: From 1.8 to 6.1 per thousand in 14 years. Rev Esp Cardiol 64(5): 424-426.

- Lecube A, Monereo S, Rubio MÁ, Martínez-de-Icaya P, Martí A, et al. (2017) Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of obesity. 2016 position statement of the Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr 64(Suppl 1): 15-22.

- Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, et al. (2016) American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines for Medical Care of Patients with Obesity. Endocr Pract 22(Suppl 3): 1-203.

- Jantaratnotai N, Mosikanon K, Lee Y, McIntyre RS (2017) The interface of depression and obesity. Obes Res Clin Pract 11(1): 1-10.

- Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, et al. (2010) Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(3): 220-229.

- Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, Schmidt WE, Montanya E, et al. (2009) Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: A 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet 374(9683): 39-47.

- Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, Garcia-Hernandez PA, Rodriguez-Pattzi H, et al. (2009) Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): A randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet 373(9662): 473-481.

- Marre M, Shaw J, Brändle M, Bebakar WM, Kamaruddin NA, et al. (2009) Liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analogue, added to a sulphonylurea over 26 weeks produces greater improvements in glycaemic and weight control compared with adding rosiglitazone or placebo in subjects with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-1 SU). Diabet Med 26(3): 268-278.

- Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, Shah NS, Tankova T, et al. (2009) Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: The LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)-2 study. Diabetes Care 32(1): 84-90.

- Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, Sethi BK, Lalic N, Antic S, et al. (2009) Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met+SU): A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 52(10): 2046–55.

- Zinman B, Gerich J, Buse JB, Lewin A, Schwartz S, et al. (2009) Efficacy and safety of the human glucagon-likepeptide-1 analog liraglutide in combination with metformin and thiazolidinedione in patients with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-4 Met+TZD). Diabetes Care 32(7): 1224-1230.

- Mezquita Raya P, Reyes Garcia R, Moreno Perez O, Escalada San Martin J, Ángel Rubio Herrera M, et al. (2015) Clinical Effects of Liraglutide in a Real-World Setting in Spain: Diabetes-Monitor SEEN Diabetes Mellitus Working Group Study. Diabetes Ther 6(2): 173-185.

- Knop F, Vilsbøll T, Højberg P, Larsen S, Madsbad S, et al. (2007) Reduced incretin effect in type 2 diabetes: Cause or consequence of the diabetic state? Diabetes. 56(8):1951-1959.

- Nauck M, Stockmann F, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W (1986) Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 29(1): 46-52.

- Toft-Nielsen MB, Damholt MB, Madsbad S, Hilsted LM, Hughes TE, et al. (2001) Determinants of the impaired secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86(8): 3717-3723.

- Vilsboll T, Krarup T, Deacon CF, Madsbad S, Holst JJ (2001) Reduced postprandial concentrations of intact biologically active glucagon-like peptide 1 in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 50(3): 609-613.

- (2020)European Medicines Agency. Ozempic summary of product characteristics.

- Tofé S, Argüelles S, Mena E, Serra G, Codina M, et al. (2021) An Observational Study evaluating effectiveness and therapeutic adherence in patients with type 2 Diabetes initiating dulaglutide vs. subcutaneous semaglutide in Spain. Endocrine and Metabolic Science 2(31): 100082.

- Mody R, Yu M, Nepal B, Konig M, Grabner M (2020) Adherence and persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes initiating dulaglutide compared with semaglutide and exenatide BCise: 6-month follow-up from US real-world data. Diabetes Obes Metab 23(1): 106-115.

- Matza LS, Boye KS, Jordan JB, Norrbacka K, Gentilella R, et al. (2018) Patient preferences in Italy: Health state utilities associated with attributes of weekly injection devices for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Patient Prefer Adherence 12: 971-979.

- Edelman SV, Polonsky WH (2017) Type 2 Diabetes in the Real World: The Elusive Nature of Glycemic Control. Diabetes Care 40(11):1425-1432.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...