Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4749

Case Report(ISSN: 2637-4749)

Ultrasonic Debridement with Stem Cell Therapy of Suspensory Branch Desmitis in an Equine Patient Volume 2 - Issue 2

Srinath Kamineni MD*, Alan Ruggles and Hamza Ashfaq

- Department of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, USA

Received: January 13, 2019; Published: January 31, 2019

Corresponding author: Srinath Kamineni, Department of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, USA

DOI: 10.32474/CDVS.2019.02.000135

Abstract

Ultrasonic debridement as a treatment for tendinopathy and desmitis is a relatively new approach in orthopedic surgery. Previously only used in limited cases, this procedure shows promise for treating ligament-bone and tendon-bone interface injuries. We present a case study of a 2-year-old thoroughbred male horse, unable to train due to recalcitrant symptoms after extensive conservative management of suspensory branch desmitis (SBD). He was then treated with ultrasonic debridement and concurrent manubrial stem cell autograft injection, to treat the ultrasound visualized lesion. Post-surgically the patient recovered quickly, began training within 6 weeks and went onto win several races. Repeat ultrasound imaging reveals a complete restoration of the internal fiber architecture of the ligament. With a 3 year follow-up, there has been consistent training and race performance with no re-injury. This study is the first to document the successful outcome of ultrasonic debridement with concurrent stem cell injection in the treatment of equine desmitis.

Keywords:Suspensory branch ligament; Desmitis; Ultrasonic Debridement; Equine; Orthopedics

Introduction

Tendinopathy and desmitis are debilitating pathologies that can severely impact the lives of those affected. In human patients these diseases result in limited mobility and painful movement. In horses the detriment of limited mobility can lead to lameness and can mean the end of a racing career, even before it begins. In equine health almost 10% of 2-year-old thoroughbred race horses in a study consisting of 896 horses were affected by suspensory branch desmitis (SBD) [1]. Suspensory branch desmitis in thoroughbreds in training led to a 3.2 times lesser likelihood of starting as a 2-yearold and 3.6 times less as a 3-year-old [1]. 58 affected cases from the same study were compared to their maternal siblings and significant difference was found in the earnings per start as a 2-year old ($2068.19 vs 2183.01, p < 0.001) and as a 3-year-old ($2267.44 vs $4605.93, p < 0.01). As we can see there is a definite effect of SBD on race horse performance.

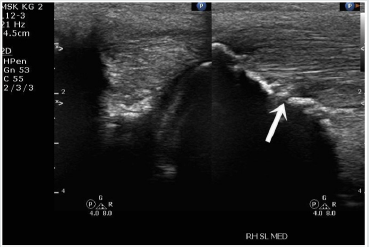

Desmitis is characterized as inflammation of a ligament due to an elastic injury from physical activity. Diagnosis of this condition is usually made with an ultrasound scan by searching for hypoechoic (darkened) bands surrounding the bone interfaces [2,1]. These darkened bands represent injured irregular fibers. In horses specifically, suspensory branch desmitis is a condition that affects the suspensory branch ligaments (SBL) and extensor branches proximal to the sesamoid bones. Symptoms include edema, fibrosis, heat, distension of the joint capsules, and pain [1]. Suspensory branch desmitis is a serious issue and if not treated properly can lead to lameness.

Currently there are only limited treatments for SBD. Previously, treatment of these conditions both in humans and horses has been limited to rest, medication, and injections [3]. Ultrasonic debridement as a treatment for tendinopathy and desmitis is relatively new to orthopedic surgery. In the past few years it has been piloted in the treatment of a few limited pathologies including patellar tendinopathy [4], diabetic foot ulcers and osteomyelitis [5,6], jumper’s knee [7], and chronic elbow tendinosis [8]. Ultrasonic debridement has the advantage of excising non-structural debris, thereby allowing regenerative cells to populate the newly cleared space [9]. The same study also showed that the collagen isomer profile present at the injury site returns to normal following the procedure. Risk of infection is low with this procedure with the following parameters: increasing amplitude of ultrasonic waves, increasing saline irrigation, increasing suction, and minimizing wound area [10].

Through the presentation of this case we aim to show that ultrasonic debridement can be a viable treatment for SBD and desmitis overall. To our knowledge this is the first study to publish evidence of ultrasonic debridement in the treatment of desmitis.

Case Details

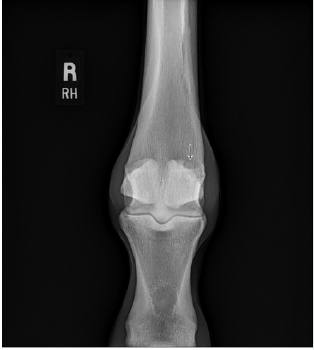

A 2-year-old thoroughbred male horse presented with medial branch suspensory desmitis. There was also associated diseased bone at the ligament bone interface on the proximal aspect of the medial sesamoid bone in the right hind leg. The patient had been unable to participate in normal training, Diagnosis was confirmed using ultrasound and X-ray scans (Figures 1 & 2). Since all conservative treatment modalities had been unsuccessful, ultrasonic debridement was chosen as the course of treatment.

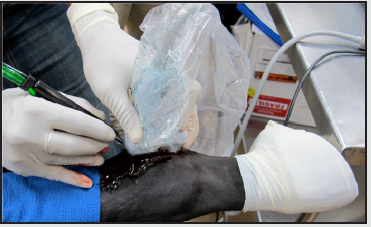

The patient was sedated and placed in a right lateral decubitus position, and closely monitored. The incision site for the ultrasonic probe entry point was marked and then the limb was prepared with alcohol and betadine. The operative area was then draped, isolating the fetlock joint of the hind right limb. Local anesthetic, 5ml of 0.5% bupivacaine, was administered to the site and a 5mm incision was made superior to the fetlock joint and distal to the carpus. The probe was introduced and positioned at the site of the lesion, using ultrasound guidance, and ultrasonic debridement was then conducted, with live ultrasound monitoring (Figure 3). The ultrasonic debridement was with the Tenex™ ultrasonic probe (Figure 4). Tissue was debrided until major hypoechoic regions were thoroughly debrided (Figure 5). Total cutting time during the operation was less than 4 minutes. Once the lesion was debrided it was injected with the previously collected and centrifuged manubrial stem cell autograft (Figure 6). The entry portal was dressed using steri-strips and a circumferential compression wrap.

During recovery patient was managed with a regular course of broad spectrum antibiotics and rest. The patient began training at 6 weeks post-surgery and the total time elapsed from surgery to first race was 15 months. Follow-up, including a repeat set of scans conducted 20 weeks post-surgery, which demonstrate the removal of the underlying bony prominence and reconstitution of the collagen fiber structure without hypoechoic regions (Figures 6 & 7). In addition, wound site had healed well with no signs of infection. No complications were observed.

Figure 7: Post-operative (20 weeks) ultrasound scan of the SBL ligament-bone interface (arrow points to healed injury site).

Discussion

Numerous surgical and nonsurgical techniques have been reported to treat SBD. In the hind limb, SBD usually has a worse prognosis than in the forelimb. While rest and rehabilitation are usually good enough to resolve lameness in 90% of horses with minor SBD in the forelimb it is much less promising for hindlimb recovery [11]. Medication including corticosteroids, hyaluronan, and glycosaminoglycans can be used in mild chronic cases but have limited efficacy for more severe cases [12]. Shockwave therapy, bone marrow/stem cell infusion, desmoplasty, urinary bladder matrix scaffolds, and fasciotomy/neurectomy have all had varying levels of success in treating SBD [13]. In a study by Crowe et al., shockwave therapy for hind leg desmitis had variable results in which ~20% of severe cases were doing reduced work and ~50% were considered lame/retired. In the same study ~10% of mild cases were doing reduced work and ~20% were lame/retired [14]. A later study by the same group found that 41% of hindlimb desmitis cases returned to full work 6 months after undergoing radial pressure wave therapy whereas 53% of forelimb cases returned to full work [15]. In a study by Herthel, 100 horses with SBD were administered intralesional autologous bone marrow transplants. 84 of them resolved lameness and returned to full work [16]. In a study by Dyson and Murray, 155 horses were treated for SBD with plantar fasciotomy and neurectomy of the deep branch plantar nerve. In the group where proximal suspensory desmitis was the only diagnosis 78% of cases returned to full work 1 year postoperatively [17]. In a study by Mitchell (qtd. in Dyson and Murray) urinary bladder matrix scaffoldings were used to treat SBD in the hind limb with an 84% success rate. A study by Hewes and White reported an 87% rate of return to full work after being treated with desmoplasty to the suspensory branch ligament [18]. Overall these results show that surgical interventions that instigate healing have a higher efficacy rate than other methods of treatment.

Our approach used a combination of manubrial stem cell autograft and surgical debridement to treat SBD. His lameness has resolved post operatively and is back in training. Postoperative success was measured by observing the thoroughbred’s performance on the racetrack and through radiologic examination. 20-week follow-up ultrasound scan showed that the darkened bands attributed to desmitis have been significantly reduced. As of April 2018, he has made 26 starts and in those starts he has had 5 first place wins, 5 seconds, and 2 thirds. Broken down by year: 2016, 6 starts, 1 first, 1 second, and 1 third; 2017, 15 starts, 2 firsts, 4 seconds, 1 third; 2018, 1 start and 1 first. He has won a total of $92,664 in prize money with an average of $3,564 per start. Compared to the average earnings of $21,340 of his paternal siblings, offspring of his sire City Zip, the horse has performed well above average. He does not appear to have had any significant time off with the longest interval of time off being close to two months. This suggests no evidence of re-injury. Overall has been able to compete as a racehorse successfully.

Results reflect successful use of ultrasonic debridement in this case of suspensory branch desmitis. We are confident that ultrasonic debridement has great potential in the future of treatment of desmitis. At this time, we are continuing to treat other equine patients and are seeing similar success.

References

- Plevin S, McLellan J (2014) The effect of insertional suspensory branch desmitis on racing performance in juvenile Thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Vet J 46(4): 451-457.

- Xie L, Spencer ND, Beadle RE, Gaschen L, Buchert MR, et al. (2011) Effects of athletic conditioning on horses with degenerative suspensory ligament desmitis: a preliminary report. Vet J 189(1): 49-57.

- Andres BM, Murrell GA (2008) Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466(7): 1539-1554.

- Nanos KN, Malanga GA (2015) Treatment of Patellar Tendinopathy Refractory to Surgical Management Using Percutaneous Ultrasonic Tenotomy and Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection: A Case Presentation. PM R 7(12): 1300-1305.

- Amini S, Shojaee Fard A, Annabestani Z, Hammami MR, Shaiganmehr Z, et al. (2013) Low-frequency ultrasound debridement in patients with diabetic foot ulcers and osteomyelitis. Wounds 25(7): 193-198.

- Michailidis L, Williams CM, Bergin SM, Haines TP (2014) Comparison of healing rate in diabetes-related foot ulcers with low frequency ultrasonic debridement versus non-surgical sharps debridement: a randomised trial protocol. J Foot Ankle Res 7(1): 1.

- Elattrache NS, Morrey BF (2013) Percutaneous Ultrasonic Tenotomy as a Treatment for Chronic Patellar Tendinopathy-Jumper’s Knee. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics 23(2): 98-103.

- Seng C, Mohan PC, Koh SB, Howe TS, Lim YG, et al. (2016) Ultrasonic Percutaneous Tenotomy for Recalcitrant Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy: Sustainability and Sonographic Progression at 3 Years. Am J Sports Med 44(2): 504-510.

- Kamineni S, Butterfield T, Sinai A (2015) Percutaneous ultrasonic debridement of tendinopathy-a pilot Achilles rabbit model. J Orthop Surg Res 10: 70.

- Michailidis L, Kotsanas D, Orr E, Coombes G, Bergin S, et al. (2016) Does the new low-frequency ultrasonic debridement technology pose an infection control risk for clinicians, patients, and the clinic environment?. Am J Infect Control 44(12): 1656-1659.

- Dyson S (2000) Proximal Suspensory Desmitis in the Forelimb and the Hindlimb. Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the AAEP pp. 137- 142.

- Smith RK (2008) Tendon and Ligament Injury. AAEP PROCEEDINGS 54: 475-501.

- White NA, Hewes CA (2008) Treatment of Suspensory Ligament Desmopathy. AAEP PROCEEDINGS 54: 502-507.

- Crowe OM, Wright IM, Schramme MC, Smith RKW (2002). Treatment of 45 Cases of Chronic Hindlimb Proximal Suspensory Desmitis by Radial Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy. Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the AAEP 2002 48: 322-325.

- Crowe OM, Dyson SJ, Wright IM, Schramme MC, Smith RK (2004) Treatment of chronic or recurrent proximal suspensory desmitis using radial pressure wave therapy in the horse. Equine Vet J 36(4): 313-316.

- Herthel DJ (2001) Enhanced Suspensory Ligament Healing in 100 Horses by Stem Cells and Other Bone Marrow Components. AAEP PROCEEDINGS 47: 319-321.

- Dyson S, Murray R (2012) Management of hindlimb proximal suspensory desmopathy byneurectomy of the deep branch of the lateral plantar nerve andplantar fasciotomy: 155 horses (2003–2008). Equine Veterinary Journal 44: 361-367.

- Hewes CA, White NA (2006) Outcome of desmoplasty and fasciotomy for desmitis involving the origin of the suspensory ligament in horses: 27 cases (1995-2004). J Am Vet Med Assoc 229(3): 407-412.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...