Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4749

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4749)

Therapeutic Plan for Clostridium Perfringens Type A Alpha Toxin Associated Jejunal Haemorrhagic Syndrome in Bovine of Tamilnadu Volume 3 - Issue 5

Krishna Kumar S1*, Ranjith Kumar M2, Vinod Kumar N3, Madheswaran R4, Anil Kumar R5, and Selvaraj P6

- 1Assistant Professor, Sheep Breeding Research Station, India

- 2Assistant Professor, Department of Veterinary Clinical Medicine, India

- 3Associate Professor, Department of Veterinary Microbiology, College of Veterinary Science, India

- 4Assistant Professor, Department of Veterinary Pathology, Veterinary College and Research Institute, India

- 5The Professor and Head, Sheep Breeding Research Station, Sandynallah, India

- 6Professor, Department of Veterinary Clinical Medicine, Madras Veterinary College, Chennai, India

Received: June 04, 2020; Published: June 17, 2020

Corresponding author: Krishna Kumar S, Assistant Professor, .Sheep Breeding Research Station, Sandynallah, The Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India

DOI: 10.32474/CDVS.2020.03.000173

Abstract

Bovine necro hemorrhagic enteritis is an emerging economically important bovine disease caused by Clostridium perfringens type A. Intestinal content of three bulls affected with Jejunal hemorrhagic syndrome were subjected for toxigenic identification of Clostridium with multiplex PCR and showed positive for Clostridium Type A alpha toxin in intestine, reticulum and in aboamsum contents. These cases lead to paralytic ileus and ended in empty rectum. This research concluded that Clostridium type A alpha toxin causes necro hemorrhagic enteritis in bovines leads to empty rectum. Treatment with Sulphadimidine, charcoal and kaolin indicated good clinical recovery

Keywords: Bovine, necrohaemorrhagic enteritis,Clostridium perfringens type A, alpha toxin, Tamilnadu

Introduction

Bovine necrohaemorrhagic enteritis is caused by Clostridium perfringens, which cause death with necro-haemorrhagic lesions in small intestine[1]. Clostridium perfringens pandemic in nature which presents in soil, sewage, food, feces and the normal intestinal microbiota of humans and animals. C. perfringens classified into five toxinotypes which includes A, B, C, D and E based on the presence of genes encoding four major toxins: alpha, beta, epsilon and iota toxin [2]. C. perfringens type A strains are the suspected etiological agent for bovine alimentary tract pathological lesions and abomasitis[3]. Even though the type A toxigenic Clostridium perfringens presents in the normal microflora of ruminants, risk factors like high carbohydrate, low fiber diet, low quality and quantity fiber feed will attract the disease [4]. Empty rectum caused by alpha toxigenic clostridium infection. Identification of toxin genes rather than the toxins they produce will help to identify the prevailing C. perfringens types in bovine cases [5]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) will be the better diagnostic method to demonstrate the encoding genes in these bacteria [6]. This paper focuses the epidemiological risk factors, clinical course and therapeutic management of necro hemorrhagic type A toxigenic C. perfringens in bovine of Tamil nadu in India.

Materials and Methods

Location

This research was carried in an organized cattle farm located in Udhagamandalam coordinates with 11.4064° N, 76.6932° E situated in southern peninsula of India. The animals were fed with green grass, roughage and concentrate in the sub recommended level. Routine deworming and vaccination were carried out.

Clinical and Laboratory Examination

A Holstein Friesian crossbred 2 year-old bull (Bull no:1) with clinical history of anorexia, dull, hemorrhagic enteritis, depressed with normal body temperature was brought for expert opinion. Routine clinical examination and rumen fluid examination were carried out. Clinical samples like whole blood, serum, dung and peripheral blood smear were collected.Medical management with parental administration of Streptopenicillin, the animal was died and detailed postmortem was carried out. Complete blood counts were analyzed with whole blood. Samples from stomach and intestinal content, vital organs were collected for toxin identification; tissues were fixed in 10% formalin for histopathology. The second animal (bull no: 2) was 2 years and 6 months old also showed hemorrhagic enteritis (Figure 1). Third animal (bull no:3) was 3 years old; also showed hemorrhagic enteritis and dung samples were subjected for toxin identification. The intestinal contents and dung samples were inoculated into Robertson’s cooked meat medium with brain heart infusion broth and incubated at 37°C for 24 h in McIntosh Field’s anaerobic jar containing Anaero-Higas pack with indicator. The DNA was extracted from C. perfringens by high salt treatment method described [7]. Single colonies of C. perfringens isolates were picked up randomly with a sterile loop and DNA was extracted. Oligonucleotide primers specific to alpha, beta and epsilon toxins of C. perfringens were adapted from previous workers [8] the multiplex PCR was performed using a thermo cycler (Kyratech, USA) as described [9].

Results

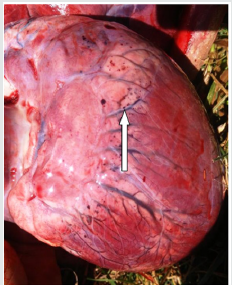

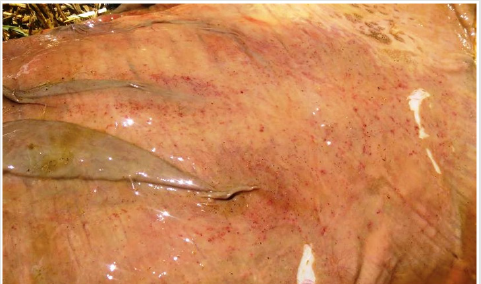

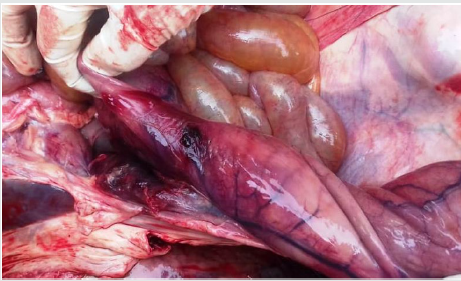

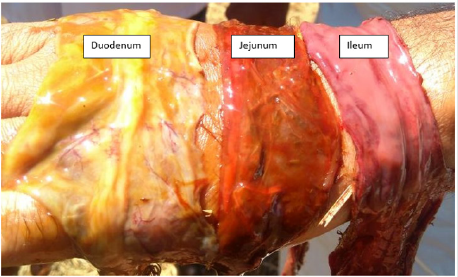

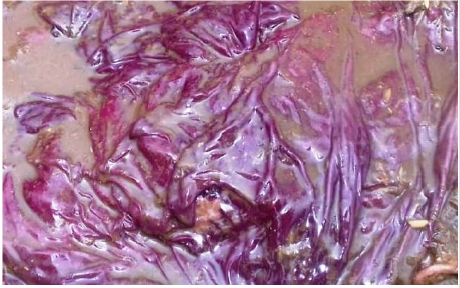

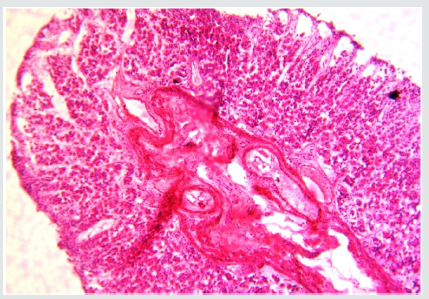

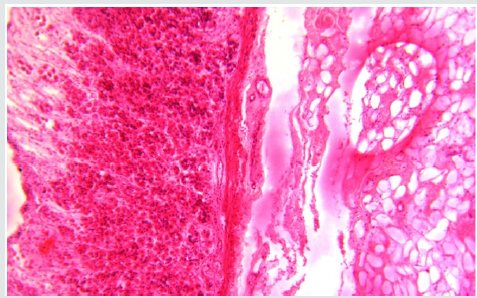

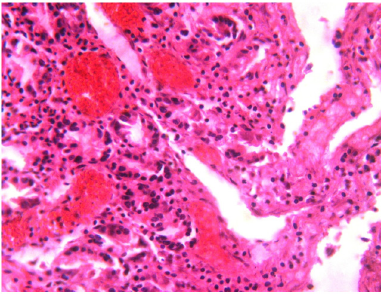

Clinical examination of bull 1 and 2 showed dull, depressed, anorexia, sunken eye ball, > 8% dehydration and ruminalatony. Body temperature was within normal range and rectal examination showed scanty dung with mucous coated. Rumen fluid examination showed few medium size protozoa per field with complete absence of small and large size protozoa. Dung samples showed negative for helminthic eggs with absence of blood protozoan etiologies. Complete blood counts showed marked nutrophilia and normal hemogram. Bull no 1 and 2s were treated with Streptopenicillin, fluid therapy and B complex injection. Animals showed poor response towards the medical management and died. Postmortem examination of intestine showed ballooning (Figure 2), necrosis, dark red in color and hemorrhagic in nature (Figures 3-6). Petechial hemorrhages noticed in auriculoventricular junction of heart (Figure 7&8) and hemorrhage was noticed in abomasum (Figures 9&10). Microscopical examination of the intestine showed hemorrhages and congestion in the mucosa and submucosa. Moderate edema and mononuclear cell infiltrations were noticed in the submucosa(Figures 11-13). The multiplex polymerase chain reaction revealed positive for type A alpha toxin of Clostrodium perfringens in recticulum and jeuenum contents and negative in ileum contents. Third animal dung was showed positive for alpha toxin of Clostridium perfringens and treated with parental sulphadimidine, charcoal and kaolin and eventual clinical recovery was noticed.

Figure 3: Dark reddish discoloration of the intestinal serosal surface indicating severe congestion (bull 1).

Figure 4: Dark reddish discoloration of the intestinal serosal surface indicating severe congestion and haemorrhages with engorged blood vessels (bull 2).

Figure 5: Diffuse severe hemorrhagic ulceration of different segments of intestine like duodenum, jejunum and ileum of bull no 1.

Figure 7: Petechiael hemorrhage with engorged blood vessesls on the epicardial surface of the heart and auriculoventricular junction of bull no 1.

Figure 9: Purple discoloration of abomasum indicating severe congestion with ulcer and necrosis in bull no 1.

Figure 11: Histopathology of jejunum mucosa showed moderate mononuclear cell infiltration in bull no 1.

Figure 12: Histopathology of jejunum showed moderate congestion of mucosa and submucosal edema in bull no 1.

Figure 13: Histopathology of ileum showed severe congestion and mononuclear cell infiltration in the mucosa of bull no 1.

Discussion

The epidemic of the necro hemorrhagic enteritis / jejunal hemorrhagic syndrome (JHS) is a upcoming disease in cattle of southern peninsula of India. Most of the dairy farms in India following low quality and quantity fiber diet pattern. But high fiber diet would believe to protect the ruminants from gastrointestinal diseases [10]. Low quantity fiber will alter the microflora of intestinal composition to favor overgrowth of Clostridium (Table.1). Most of the cases of JHS recorded within 5 years of age [11]. As per epidemiological investigations, higher susceptibility in Holstein Friesian was due to genetic influence [11]. And recorded in good to excellent built animals [12]. First of its kind, the necro hemorrhagic enteritis by Clostridium Type An alpha toxin in India was documented. This case was eventually designated as haemorrhagic bowel syndrome (HBS) or jejunalhaemorrhage syndrome (JHS) as mentioned [1and 13]. Winter season precipitate high cold condition with higher toxin production[15]. The blood profile expressed as marked nutrophila which indicated the infection in progress. The stressful risk factors like low fiber diet will cause paralytic ileus which cause abnormal changes in the microflora like expression of toxigenic genes, which produces toxin leads to intestinal hemorrhage [16]. Clostridium perfringens type aapha toxin was identified in recticulum, abomasum and jejunum [17]. As per the case control study model, affected animals group were purchased from northern part of India where the feed ingredients were entirely different form the present epidemic area since some of the feed ingredient would trigger the multiplication of Clostridium perfringens Type a alpha toxin [18]. But animals purchased from local areas where same package of practices were followed and had no/low incidence of this infection. Risk factors would increase the intestinal permeability, impair the intestinal peristalsis motility which blocks the beneficial flushing effect of intestinal transport and favors for bacterial/toxin over production [19]. Clinical sign and pathophysiology were highly complicated like intussception, volvulus and paralytic ileus depending upon the stage and severity of the pathology of Clostridium type A alpha toxin (Table 3). On post mortem examinations of bull no 1 and 2 animals showed necrosis and hemorrhages in jejunum and abomasum (Table1) mostly called as clostridialabomasitis[20].The lesions of necro- haemorrhagic – jejuno - ileitis observed in cattle enterotoxaemia with toxinotype A strain was well explained by the hypothesis of a synergy between the ß1 toxin and a ß2 toxin variant [21].Upon treatment with parental sulphadimidine @ 333 mg/kg.bwt (IV), Kaolin powder (1g/kg.bwt), activated Charcoal (0.5g/kg.bwt) orally , there was marked recovery of bill no 3.(Table2). Risk factors included low quantity and quality fiber feed, sudden change of carbohydrate –protein source in ration would be managed efficiently to prevent the epidemic of Clostridium perfringens Type A alpha toxin in dairy animals.

Table 2: Clinical course of necro hemorrhagic enteritis of Clostridium perfringens Type A alpha toxin in cross bred cattle.

Conclusion

Clostridium perfringens Type a alpha toxigenic enteritis in cross bred cattle will have nerco hemorrhagic enteritis which is otherwise called Jejunal hemorrhagic syndrome (JHS)/ Hemorrhagic bowl syndrome. The clinical course with simple anorexia and end up in necro hemorrhagic enteritis. This case was successfully managed with parental sulphadimidine, Kaolin and activated Charcoal orally. Nowadays feeding of low quantity fiber feed and high volume of concentrated feeding practices attracts the Clostridial overgrowth which in turn produces type A alpha toxin causes hemorrhagic inflammatory spots in intestine which pave way for intussception, obstruction, paralytic ileus and empty rectum. Upon earlier therapeutic plan with parentralSulphadimidine, Kaolin and Charcoal orally with sufficient rehydration of fluids and electrolytes will save the animals. Avoiding risk factors included low quantity and quality fiber feed, sudden change of carbohydrate – protein source in ration will prevent the epidemic of Clostridium perfringens Type A alpha toxin in dairy animals.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing Interests

None declared.

References

- Lebrun M, Mainil JG, Linden A (2010) Cattle enterotoxaemia and Clostridiumperfringens: description, diagnosis and prophylaxis. Vet Rec 167:13-22.

- Songer JG, Meer RR (1996) Genotyping of Clostridium perfringens by polymerase chain reaction is a useful adjunct to diagnosis of clostridial enteric disease in animals. Anae 2: 197-203.

- Petit L, Gibert M, Popoff MR (1999) Clostridium perfringens: toxinotype and genotype. Trends Microbiol 7:104-110.

- Roeder BL, Chengappa MM, Nagaraja TG, Avery TB, Kennedy GA (1988) Experimental induction of abdominal tympany, abomasitis, and abomasal ulceration by intraruminal inoculation of Clostridium perfringens type A in neonatal calves. Am J Vet Res 49:201-207 .

- House JK, Smith GW, McGuirk SM, Gunn AA, Izzo M (2014) Manifestations and management of disease in neonatal ruminants. In: Smith BP (Eds.),Large animal internal medicine. Mosby Elsevier, St, Louis, USA, p. 5.

- Rood JI, Cole ST (1991) Molecular genetics and pathogenesis of Clostridium perfringes. Microbiol Rev 55(4): 621-648.

- Carter GR (1984) Diagnostic Procedure in Veterinary Microbiology. Charles C Thomas, Springfield, Illinois Abutarbush SM, Radostits OM (2005) Jejunal hemorrhage syndrome in dairy and beef cattle: 11 cases (2001 to 2003). Canadian Veterinary Journal 46: 711-715.

- Ramadoss P (2006) DNA isolation from bacteriological culture using high salt method, ICAR workshop on emerging biotechnological methods on disease diagnosis, Department of Animal Biotehcnology, MVC, Chennai.

- Songer JG (1996) Clostridial enteric diseases of domestic animals. ClinMicrobiol Rev 9:216-234

- Vinod Kumar N, Sreenivasulu D, Reddy YN (2014) Prevalence of clostridium perfringens toxin genotypes in enterotoxemia suspected sheep flocks of Andhra pradesh, Veterinary World 7(12): 1132-1136.

- Manteca C, Daube G, Jauniaux T, Limburg B, Kaeckenbeeck A, Mainil J (2000) Study of bovine enterotoxemia in Belgium. II. Basic epizootiologyand descriptive pathology. Ann Med Vet 145: 75-82

- Manteca C, Daube G, Pirson V, Limbourg B, Kaeckenbeeck A, et al. (2001) Bacterial intestinal flora associated with enterotoxaemia in Belgian Blue calves. Vet Microbiol81:21-32.

- Ceci L, Paradies P, Sasanelli M, De CaprariisD, Guarda F,et al. (2006) Haemorrhagic bowel syndrome in dairy cattle: possible role of Clostridium perfringens type A in the disease complex. Journal of Veterinary Medicine. A, Physiology, Pathology, Clinical Medicine 53: 518-523.

- Dennison AC, VanMetre DC, Callan RJ, Dinsmore P, Mason GL, et al. (2002) Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome in dairy cattle: 22 cases (1997-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc221:686-689.

- Husebye E (2005) The pathogenesis of gastrointestinal bacterial overgrowth.Chemotherapy 51(1):1-22.

- Niilo L, Moffatt RE, Avery RJ (1963) Bovine “enterotoxemia”. II. Experimental reproduction of the disease. Can Vet J 4:288-298.

- Barratt ME, Strachan PJ, Porter P (1978) Antibody mechanisms implicated in digestive disturbances following ingestion of soya protein in calves and piglets. ClinExpImmunol 31:305-312.

- Huerta-Franco MR, Vargas-Luna M, Montes-Frausto JB, Morales-Mata I, Ramire Padilla L (2012) Effect of psychological stress on gastric motility assessed by electrical bio-impedance. World J Gastroenterol 18:5027-5033.

- Lebrun M, MainilJG, Linden A (2010) Cattle enterotoxaemia and Clostridium perfringens: description, diagnosis and prophylaxis, Veterinary Record 167: 13-22

- Valgaeren BR, Pardon B, Verherstraeten S, Goossens E, Timbermont L, et al. (2013) Intestinal clostridial counts have no diagnostic value in the diagnosis of enterotoxaemia in veal calves. Vet Rec 172: 237.

- Lebrun M, Mainil JG, Linden A (2010) Cattle enterotoxaemia and Clostridium perfringens: description, diagnosis and prophylaxis. Vet Rec 167:13-15.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...