Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5760

Case Report(ISSN: 2690-5760)

Vertebral Osteomyelitis: The Secret in the Teeth Volume 4 - Issue 2

Christina Onyebuchi, MS31, Michael Thornton, MS31, Moe Ameri, MD, MSc2*, Kevin Brown, MD2 and Bernard M Karnath, MD, FACP2

- 1School of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, USA

- 2 Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, USA

Received:December 01, 2021; Published: December 14, 2021

Corresponding author: Moe Ameri, MD, MSc, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, 301 University Boulevard, Galveston, TX, USA

DOI: 10.32474/JCCM.2021.04.000182

Abstract

Introduction: Osteomyelitis and other vertebral infections secondary to Parvimonas micra infection are rare but should be considered in patients with an immunocompromised state or recent dental infection. We present a case of Parvimonas micra discitis and osteomyelitis with discussion of diagnostic workup and treatment guidelines.

Case report: We report the case of a 57-year-old female with a history of chronic back pain and severe spinal stenosis who presented with worsening lower back pain found to have infection with Parvimonas micra after bone biopsy and disc aspiration. Surgical intervention was not performed due to the lack of neurological deficits and low likelihood of acute infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin and ceftriaxone, with subsequent oral antibiotics.

Discussion: Parvimonas micra is an anaerobic, gram-positive cocci that commonly resides in the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory tract. When deciding how to treat vertebral osteomyelitis it is important to discern if the patient has clinical signs of neurologic deficits. This is true because the presence of neurologic deficits may elucidate the need for surgical intervention. Finally, reiterating the importance of considering patient risk factors and socioeconomic status for tailoring treatment regimen.

Introduction

Osteomyelitis is an infection of the bone. Osteomyelitis generally arises hematogenously or via conterminous infection. Moreover, osteomyelitis is classified as acute which generally arises within 2 weeks of the infection which presents with inflammatory bone changes. Chronic osteomyelitis typically manifests itself after 6 weeks from the initial infection. The hallmark of chronic osteomyelitis is bone destruction. The pelvis, clavicle, long bones and vertebrae all stand as common locations of osteomyelitis. Common causative organisms include Staph Aureus, Candida, Pseudomonas, and naturally occurring oral flora. The causative agent may correlate with patient behavior. For example, people who inject IV drugs and contaminate the needle with oral saliva before puncturing the skin may be present with osteomyelitis due to oral bacterial flora. Patients who are bitten by animals tend to get cellulitis in the hand or proximal to where the puncture wound occured. In summary, osteomyelitis can present itself in a myriad of ways.

Case Report

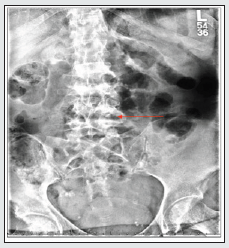

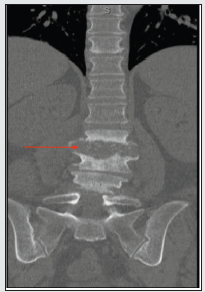

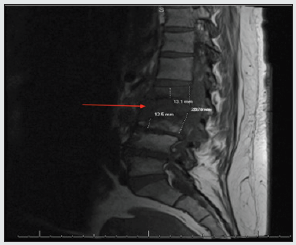

A 57-year-old female with a past medical history of chronic back pain and severe L3-L5 spinal stenosis, presented to the emergency department with acute-on-chronic lower back pain. The patient’s medical history also included newly diagnosed hepatitis C virus infection, alcoholic fatty liver disease, polysubstance abuse, alcohol use disorder, COPD, and hypertension. The patient reported an extensive history of lower back pain that was progressively worsening over the past several weeks. Physical examination was significant for paravertebral tenderness, reduced range of motion and ambulation secondary to pain, and clonus of the bilateral lower extremities. No neurological deficits were found on the exam. On presentation, the patient had mild leukocytosis, but laboratory results were otherwise unremarkable. Imaging performed in the ED was suggestive of discitis and osteomyelitis of the L2-L3 lumbar spine (Figure. 1). Neurosurgery evaluated the patient and did not recommend surgical intervention at that time. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed inflammatory changes of discitis osteomyelitis at the level of L2-L3, with signs of early osteomyelitis at L4-L5 (Figures. 2 & 3). A bone biopsy of the lumbar spine and aspiration of the intervertebral disc was performed by Interventional Radiology. Although the bone biopsy was negative for organisms, cultures of the aspiration from the intervertebral disc was positive for Parvimonas micra. Blood cultures showed no growth to date. Upon additional questioning, the patient reported having a toothache for the past several weeks and was not able to seek proper dental care. Further investigation of the oral cavity identified a right upper molar infection. During admission, the patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin and ceftriaxone. She was then transitioned to two weeks of oral ampicillinsulbactam, followed by an additional two weeks of oral amoxicillin and clavulanic acid to ensure complete clearance of the infection. The patient showed improvements in mobility and pain and was stable for discharge after 12 days of hospitalization.

Discussion

Parvimonas micra is an anaerobic, gram-positive cocci that commonly resides in the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory tract [1]. This microorganism typically presents in patients with dental abscesses, those who contamine intravenous needles with oral saliva prior to injection, and immunocompromised individuals. In this case presentation, the patient had poor dentition and a known history of intravenous drug abuse. A combination of these risk factors could have likely been the source of discitis and osteomyelitis caused by Parvimonas micra infection. The causative agent of the patient’s infection, Parvimonas micra is an anaerobic gram-positive cocci that commonly resides in the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, or respiratory tract [1]. Patients with dental abscesses and those who contaminate IV needles with oral saliva before injection should be considered at risk for contracting a Parvimonas infection. Our patient had poor dentition as well as a known history of IV drug use. Both of which could have been the source of the Parvimonas micras infection in her vertebrate. Vertebral osteomyelitis is usually the result of hematogenous spread, which further bolsters our initial thought that the Parvominas infection in this patient originated from an outside source [2]. When deciding how to treat vertebral osteomyelitis it is important to discern if the patient has clinical signs of neurologic deficits. This is true because the presence of neurologic deficits may elucidate the need for surgical intervention [3].

Our patient did not show signs thus we decided that surgical intervention was not merited. We instead opted to opt for a CT-guided needle biopsy in order to determine the causative agent and subsequently treat with appropriate antibiotics. Standard treatment for vertebral osteomyelitis usually consists of antibiotics for 6 weeks [3]. The extended treatment protocol made our antibiotic regime more complex. Furthermore, our patient’s socioeconomic status and prior history of IV drug use prompted us to minimize the amount of time that the patient would receive antibiotics intravenously. As a result, the Infectious Disease Team was consulted and recommended a switch to per oral medications after the IV Zosyn course was completed [3]. This case illuminated the importance of considering patient risk factors and socioeconomic status for antibiotic treatment. Furthermore, doctors should consider examining patient history when trying to identify the source of a Parvimonas infection. Our patient had two possible key risk factors which may have been the cause of the rare bacterial infection.

References

- Tindall BJ, Euzéby JP (2006) Proposal of Parvimonas gen. nov. and Quatrionicoccus gen. Nov. as replacements for the illegitimate, prokaryotic, generic names Micromonas Murdoch and Shah 2000 and Quadricoccus Maszenan et al. 2002, respectively. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 56(Pt 11): 2711-2713.

- Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, Rabih O Darouiche, Andreas F Widmer, et al (2015) Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Native Vertebral Osteomyelitis in Adults. Clin Infect Dis 61(6): e26-46.

- Lemaignen A, Ghout I, Dinh A, Guillaume Gras, Bruno Fantin, et al (2017) Characteristics of and risk factors for severe neurological deficit in patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: A case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore) 96(21): e6387- e6394.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...