Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5760

Mini Review(ISSN: 2690-5760)

Post Operative Fever After Gynecological Surgeries Volume 3 - Issue 3

Brinderjeet Kaur*

- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Santokba Durlabhji Memorial Hospital and Research Center, India

Received:July 26, 2021 Published: August 06, 2021

Corresponding author:Brinderjeet Kaur, Consultant, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Santokba Durlabhji Memorial Hospital and Research Center, Jaipur, India

DOI: 10.32474/JCCM.2021.03.000165

Abstract

Post-operative fever is common after majority of gynecologic surgeries. Although most of the fever is physiological after surgery with self-resolution some require meticulous investigations. Where in spite of all diagnostic work up, no apparent cause of fever is detected it is prudent to discharge the patient. In a resource limited country, a balance needs to be maintained between the investigational cost and affordability of patients. The paper gives simplified view of the various causes and diagnostic as well as treatment approach.

Keywords: Postoperative Fever; Gynecological Surgery; Surgical Site Infection

Introduction

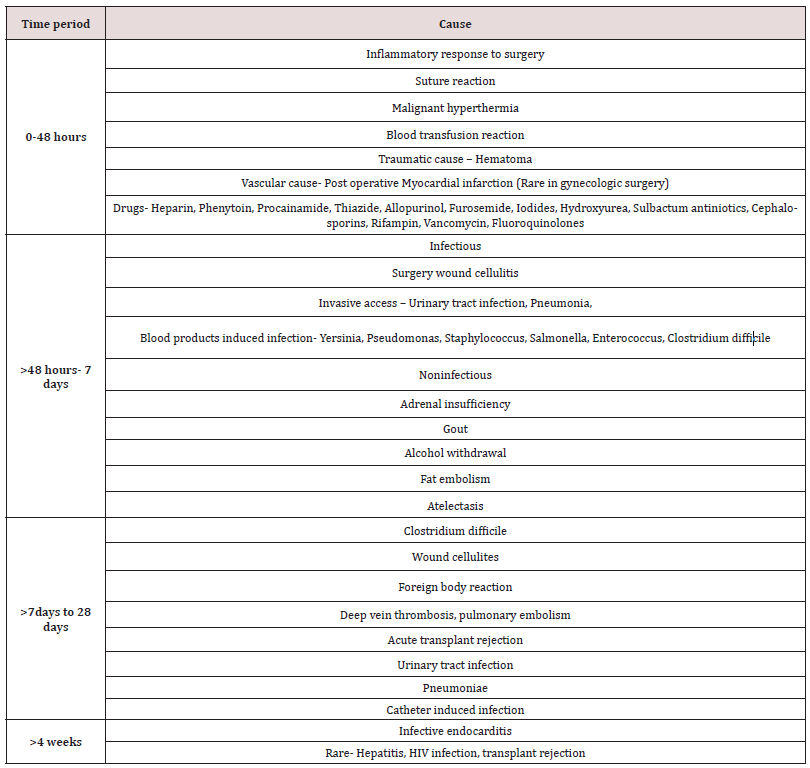

Fever is caused by release of pyogenic cytokines as a part of body’s normal response to tissue injury from surgery. The most important factor that one should bear in mind while working on the etiology of fever is the time elapsed between the surgery and onset of fever, as approximately 80% of fever within first post-operative day is self-limiting with spontaneous recovery [1,2]. Surgical site infections although are low for minimally invasive surgeries but it’s incidence in abdominal hysterectomy is 4% [3]. Hysterectomy is one of the common gynecologic surgical procedures in reproductive age group [4]. There have been increased role of minimally invasive procedures but still majority of hysterectomies continue to be performed abdominally (54.2%) followed by vaginally (10.7%), laproscopically (8.6%) [5]. Gynecologic surgeries are unique as the potential for post-operative infections is higher than any other type of surgery; it is attributed to the potential of pathogenic microorganisms to ascend from breached vagina and endocervix to the operative site. In addition to this the vaginal flora is a complex milieu of gram positive and gram-negative microorganisms posing increased risk for post-surgical fever [6,7]. Fever is defined as temperature greater than 38 °s C (100.4 °F) and persisting for more than two post-operative days [8]. Adjusting for diurnal variations an oral temperature more than 37.2 °s C (98.9 °F) on morning and evening temperature of greater than 37.7 °s C (99.8 ° F) qualifies as fever. In most of the cases the fever is self-limiting with no additional treatment needed except for observation. [9] At the same time it is important to identify the small population of patients who require evaluation of cause and treatment. Generally, fever within 48 hours of surgery is due to inflammatory response proportional to tissue damage and self-resolving within 2-4 days. There are two conditions where fever occurring within 48 hours of surgery could be critical-Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) and in transplant recipient [10]. Nursing staff plays the role of leader in patient care especially at times when the person (patient) is unable to take control of his/ her day-to-day activities due to debilitating disease or infirmity. They are entrusted with the responsibility of delivering tailored patient specific treatment, providing necessary information to patients -attendants and by providing as well as creating an environment that is best conducive for patient. It is therefore of utmost importance that nursing staff is well versed with post-operative fever etiologies so that they can bring best patient care practices Table 1.

Risk Factors

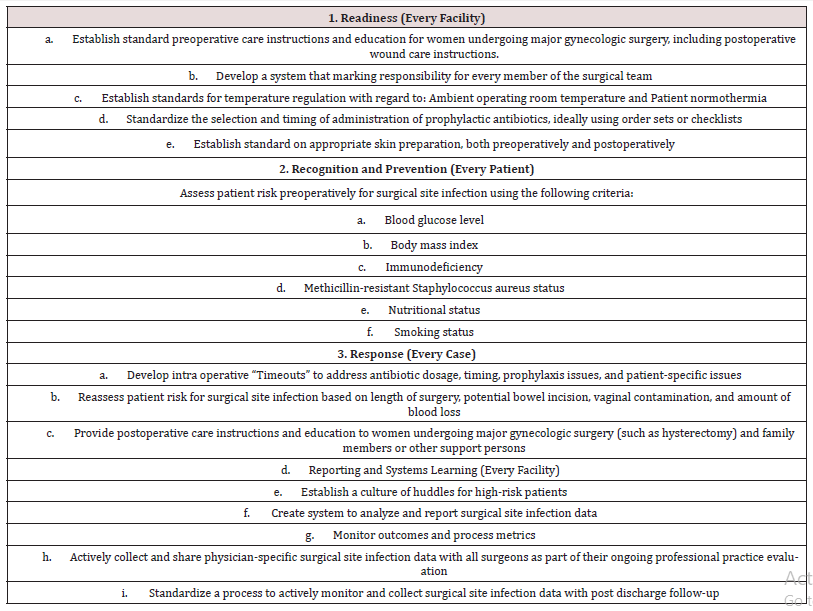

The higher incidence of post-operative fever is seen in patients having uncontrolled diabetes, smoking tendencies, prolonged use of steroids, longer hospital stay and coincidental infections [11]. Every attempt should be made to control diabetes as high glucose levels have been implicated in increased risk of post-operative infections [12,13]. Nasocomial infections could be controlled by avoiding prolonged hospital stay [14,15]. Bacterial vaginosis is also implicated in post-operative infections leading to post-operative fever therefore ore surgical screening for bacterial vaginosis should be done in patients who undergo hysterectomy [16,17]. It is advisable to surgeons to treat bacterial vaginosis with metrinidazole and add it to ampicillin sulbactum if positive results are noted. Single port laparoscopic hysterectomy has lower infection rate than 4 port procedure [18]. The American college of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG) emphasize on reduction of post-operative surgical infections after gynecologic surgical procedures as these surgeries outnumber any other class of surgeries and are very commonly done worldwide [19]. The safety bundle is organized into four domains: Readiness, Response, Reporting and system learning. Table 2 shows safety bundles for prevention of surgical site infections following major surgery.

Team Effort

Prevention of surgical site infection is responsibility of each and every member of Perioperative team which includes surgeon, anesthesia provider, nurse(s) and other members of team. It is always in the best interest of patient that they are provided with clear, crisp instructions in writing pertaining to skin preparation, cleansing solutions and prophylactic antibiotics. Anesthesia providers should ensure that the patient receives antibiotics in timely manner as well as intra operative glycemic control and maintenance of normothermia during surgery. The role of antibiotic prophylaxis was first emphasized by Burke et al. [20]. The surgical care improvement teams have suggested prophylactic antibiotic administration within 60 minutes before surgical incision. For antibiotics that are given by slow infusion 120 minutes prior to surgical incision was recommended [21]. A multicenter study by Steinberg et al. [22] in 2009 examined the relationship between timing of antibiotic dosing and surgical site infection. They suggested that antibiotics can be primed (0-30 min) before skin incision. In the study by Savage et al. [23] in 2013, it was found that the risk of surgical site infection was 6.3% for procedures under 1 hour and for procedures lasting 2 hours the risk increased to 28%. Therefore, antibiotics should be dosed for longer surgical procedures and those with substantial blood loss (blood loss more than 1500 ml). Bratzler et al. [24] in 2013 suggested that antibiotic dosing should be done for one to two times the half-life of drug measured from the time of pre-operative dosing. As far as the choice of antibiotics is concerned it is often recommended that the antibiotic should be based on the type of surgery and wound classification [25]. Cephalosporin is the choice of antibiotics for common abdominal gynecological procedures as they are active against common skin pathogens S aureus and Streptococcus species. In case of penicillin allergy or MRSA infection a modified antibiotic region should be administered and collaboration between anesthesia provider and surgical staff is required to ensure that desired dose is given in an acceptable time. There is lack of compelling evidence from literature as regard to extended duration of antibiotics as prophylaxis in absence of clear medical indications as evidence by studies from Bratzler & Hock et al. [26]. Therefore, all prophylactic antibiotics should be terminated within 24 hours of surgery completion.

Normothermia And Thermal Regulation

A temperature less than 35 °C is hypothermia. Normothermia depends on the type of anesthesia, warming devices and operating room temperature. Propofol and opioids result in impaired thermoregulation [27]. Hypothermia causes vasoconstriction that results in decrease tissue oxygenation leading to impaired immune function [28]. The literature studies reinforce the importance of preservation of normothermia during the operating procedure. Perioperative warming could be achieved by using warm intravenous fluids with or without using a forced air warmer [29] Scott [30] in their study found that by effective normothermia complications like pressure ulcers transfusion reactions and postoperative cardiac events are reduced.

Risk Assessment Factors

Glycemic control

Hyperglycemia in postoperative period in a non-diabetic patient causes risk of surgical site infection [31]. Al Niami et al. [32] in 2015 in their study in gynecological malignancies found that post 24-hour glycemic control lowered the surgical site infection rate by 35%. Surgical stress and preoperative anxiety may also contribute to impaired glycemic control during surgery and therefore needs to be addressed timely.

Obesity

Abdominal hysterectomy in patients with high body mass index poses risk of wound complications [33]. An overnight weight reduction is neither possible non practical solution, but it has been recommended by ACOG practice 2015 [34] to use subcutaneous sutures, talc application or Wound Vacuum home postoperatively to minimize the risk of wound infections.

Nutritional status and immunity

Daniel [35] in their study have found that well-nourished patients respond and recover well after surgery therefore healthcare providers must not neglect nutritional care of patient both before and after surgery. The use of steroids drugs and disease affecting immunity impair the ability to resist against infections and their occurrence in patients mandates special care by the preoperative team [36]. Preoperative MRSA screening helps in the choice of appropriate antibiotic therapy as illustrated in studies by Kavangh et al. [37].

Personal habits

Sorenson et al. [38] in their study found higher infection rate in smokers 12% against 2% in nonsmokers. A 4-week abstinence from smoking significantly reduces wound infection chances. It is always best to prepare safety checklist by all surgical team members to develop teamwork and timely address the caveats that contribute to surgical site infection. Post-operative instructions to patients and their attendants should be given by the medical care team as they are vital for favorable outcome in terms of surgical site infections. Brief communication between team members monitoring outcome for identifying patients, data collection and active monitoring including post-discharge follow-up are some of the strategies that help the healthcare provider in tackling post-surgical infection.

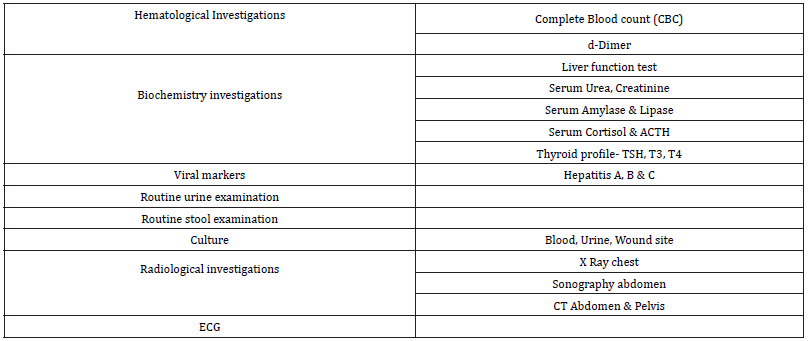

The Work Up

The main aim of work up is to know the underlying conditions and symptoms that indicate towards an etiology unrelated to postsurgical inflammatory response. The multistep approach including history taking, examination and systemic examination is given below.

a. Timing and duration of invasive catheterization and intubation should be noted.

b. Identify anesthetic medications and blood products used during and immediate after surgery.

c. Pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis.

d. Drug history.

e. Personal history of alcohol withdrawal, hyperthyroidism, underlying malignancy and pheochromocytoma indicated noninfectious etiology of fever.

f. Breathlessness with pleuritic pain and hemoptysis may be due to pleural effusion. Nasal discharge may indicate sinusitis; leg swelling may indicate DVT and should prompt diagnostic testing for d-Dimer.

g. Severe newly onset abdominal pain may indicate postoperative complications like peritonitis. Pain in suprapubic area indicates UTI.

h. In rare instances stress of surgery may indicate an exacerbation of gout or pseudo gout manifesting as joint pain and swelling.

i. Infections are likely cause of fever beyond 2 post-operative days.

j. It is rare in gynecological surgery to have meningitis, ottitis media, cavernous sinus thrombosis or fat embolism (Table 3).

It is appropriate here to remember the mnemonic for post operative fever for remembering the most common causes [39,40].

Five ‘W’ s

a) Wind- Atelectasis

b) Water- UTI

c) Walking- Deep vein thrombosis

d) Wound

e) Womb

Treatment

Antipyretics

The use of antipyretics as standing order to treat fever should be discouraged as it masks other symptoms that are useful and critical for evaluation of cause of fever. Aspirin and paracetamol remain the mainstay of treatment. Oral aspirin and NSAIDS might produce adverse gastrointestinal symptoms and platelet dysfunction defects [41]. Paracetamol is safe in adults for fever treatment [42].

Ionotropic and respiratory support

In situations of systemic infections leading to sepsis and shock like state – ionotropic support like adrenaline, dobutamine should be used. Seriously ill patients with poor lung perfusion and oxygenation should be provided with respiratory support.

Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotics if possible should be given after culture and sensitivity and in case of prophylactic antibiotics the choice to be governed by the nature of surgery and patient factors. Table 4 highlights the antibiotic therapy for gynecological surgeries.

Fluid resuscitation

Septic shock is a dreaded complication following infections. It is advisable to maintain adequate plasma volume by using gelatin, crystalloids, blood/ blood product transfusion and starch solutions.

Surgical options

Elimination of source of infection by drainage of pus or excision of diseased organ could sometimes be undertaken for controlling infection.

Conclusion

It is of paramount importance that post-operative fever is evaluated, infectious cause if any promptly treated. An aggressive approach for finding the cause of post-operative fever should be balanced against the choice of investigations and cost benefit ratio as most of the post-operative fevers resolve automatically. In the era of evidenced based medicine, it is critical that every investigation offered to patient and done finds rationale as per the literature reviews.

Conflict of Interest

Nil

Sources of Funding

Nil

References

- Fry D (2002) Surgical infection. In: O’Leary J, editor. The physiologic basis of surgery. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins pp. 218-257.

- Wortel CH, van Deventer SJ, Aarden LA, N J Lygidakis, H R Büller, et al (1993) Interleukin-6 mediates host defense responses induced by abdominal surgery. Surgery 114(3): 564-570.

- Mahdi H, Goodrich S, Lockhart D, Robert De Bernardo, Mehdi Moslemi Kebria (2014) Predictors of surgical site infection in women undergoing hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease: a multicenter analysis using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 21(5): 901-909.

- Whiteman M K, Hillis S D, Jamieson D J, Morrow B, Podgornik M N, et al (2008). Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000–2004. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 198(1): 34.E1-34.E7.

- Wright J T, Herzog T J, Tsui J, Ananth C V, Lewin S N, et al (2013) Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstetrics & Gynecology 122(2 part 1): 233-241.

- James RC, MacLeod CJ (1961) Induction of staphylococcal infections in mice with small inocula introduced on sutures. Br J Exp Pathol 42(3): 266-277.

- Altemeier WA, Culbertson WR, Hummel RP (1968) Surgical considerations of endogenous infections-sources, types, and methods of control. Surg Clin North Am 48(1): 227-240.

- Mackowiak PA (2000) Fever. In: Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 5th edition. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Polin R, eds. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone: Philadelphia pp. 604-621.

- Garibaldi RA, Brodine S, Matsumiya S, M Coleman (1985) Evidence for the non-infectious etiology of early postoperative fever. Infect Control 6(7): 273-277.

- Fanning J, Neuhoff RA, Brewer JE, T Castaneda, M P Marcotte, et al (1998) Frequency and yield of postoperative fever evaluation. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 6(6): 252-255.

- Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson M, L C Silver, W R Jarvis (1999) Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 27(2): 247-264.

- Jamie W, Duff P (2003) Preventing infections during elective C/S and abdominal hysterectomy. Contemp Obstet Gynecol 48(1): 60-69.

- King JT, Goulet JL, Perkal MF, Ronnie A Rosenthal (2011) Glycemic control and infections in patient with diabetes undergoing non cardiac surgery. Ann Surg 253(1): 158-165.

- Groniker M, Eliasen M, Skov Ettrup LS, Janne Schurmann Tolstrup, Anne Hjøllund Christiansen, et al (2014) Preoperative smoking status and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 259(1): 52-71.

- Bueno Cavanillas, Rodrìguez Contreras R, Delgado Rodriguez M, O Moreno Abril, R López Gigosos, et al (1991) Preoperative stay as a risk factor for nosocomial infection. Eur J Epidemiol 7(6): 670-676.

- Faro C, Faro S (2008) Postoperative pelvic infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 22(4): 653-663.

- Soper DE, Bump RC, Hurt WG (1990) Bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis vaginitis are risk factors for cuff cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 163(3): 1016-1021.

- Li M, Han Y, Feng YC (2012) Single-port laparoscopic hysterectomy versus conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy: a prospective randomized trial. J Int Med Res. 40(2): 701-708.

- Kirkland K B, Briggs J P, Trivette S L, Wilkinson W E, Sexton D J (1999) The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: Attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 20(11): 725-730.

- Burke J F (1961) The effective period of preventive antibiotic action in experimental incisions and dermal lesions. Surgery 50: 161-168.

- Berenguer C M, Ochsner M G, Lord S A, Senkowski C K (2010) Improving surgical site infections: Using national surgical quality improvement program data to institute surgical care improvement project protocols in improving surgical outcomes. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 210(5): 737-741.

- Steinberg J P, Braun B I, Hellinger W C, Kusek L, Bozikis, M R, et al (2009) Timing of antimicrobial prophylaxis and the risk of surgical site infections: Results from the trial to reduce antimicrobial prophylaxis errors. Annals of Surgery 250(1): 10-16.

- Savage M W, Pottinger J M, Chiang H Y, Yohnke K R, Bowdler N C, et al (2013) Surgical site infections and cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 209(2): 108.e1-10.

- Bratzler D W, Dellinger P, Olsen K M, Peri T M, Auwaerter P G, et al (2013) Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 70(3): 195-283.

- Sullivan S A, Smith T, Chauhan S, Hulsey T, Vandorsten J P, et al (2007) Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 196(5): 455.e1-455.e5.

- Bratzler D W, Houck P M (2005) Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: An advisory statement for the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. American Journal of Surgery 189(4): 395-404.

- Qadan M, Gardner S A, Vitale D S, Lominadze D, Joshua I G, et al (2009) Hypothermia and surgery: Immunological mechanisms and current practice. Annals of Surgery 250(1): 134-140.

- Nguyen N, Yegiyants S, Kaloostian C, Abbas M A, Difronzo L A (2008) The Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) initiative to reduce infection in elective colorectal surgery:Which performance measures affect outcome? American Journal of Surgery 74(10): 1012-1016.

- Garretson S (2004) Benefits of pre-operative information programmes. Nursing Standard 18(47): 33-37.

- Scott E M, Buckland R (2006) A systematic review of the intraoperative warming to prevent postoperative complications. AORN Journal, 83(5): 1090-1104.

- Richards J E, Kauffmann R M, Obremskey W T, May A K (2013) Stress-induced hyperglycemia as a risk factor for surgical-site infection in non-diabetic orthopaedic trauma patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 27(1): 16-21.

- Al Niaimi A N, Ahmed M, Burish N, Chackmakchy S A, Seo S, et al (2015) Intensive postoperative glucose control reduces the surgical site infection rates in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecologic Oncology, 136(1): 71-76.

- Shah D K, Vitonis A F, Missmer S A (2015) Association of body mass index and morbidity after abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic hysterectomy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 125(3): 589-598.

- Association of peri Operative Registered Nurses (2015) Perioperative standards and recommended practice for inpatient and ambulatory settings. DenverCO: Author.

- Daniels L (2003) Good nutrition for good surgery: Clinical and quality of life outcomes. Australian Prescriber 26(6): 136-140.

- Savage M W, Pottinger J M, Chiang H Y, Yohnke K R, Bowdler N C, et al (2013) Surgical site infections and cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 209(2): 108.e1-10.

- Kavanagh K T, Calderon L E, Saman D M, Abusalem S K (2014) The use of surveillance and preventative measures for methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infections in surgical patients. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control 3(1): 18-25.

- Sorensen L T (2012) Wound healing and infection in surgery. The clinical impact of smoking and smoking cessation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Surgery 147(4): 373-383.

- Staffel JG, Denny JC, Eibling DE, Johnson JT, Kenna MA, et al (2005) Postoperative Fevers. In : America Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. Wax MK, editor. Chapter 3. Alexandria p. 1-7.

- Barie PS, Hydo LJ, Eachempati SR (2004) Causes and consequences of fever complicating critical surgical illness. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 5(2): 145-159.

- Graham NM, Burrell CJ, Douglas RM, Debelle P, Davies L (1990) Adverse effects of aspirin, acetaminophen and ibuprofen on immune function, viral shedding and clinical status in rhinovirus- infected volunteers. J Infect Dis 162(6): 1277-1282.

- Dinarello CA, Gelfand JA (2005) Fever and hyperthermia. In: Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 16th ed. McGrawHill p. 104-107.

- D W Bratzler, E P Dellinger, K M Olsen, Trish M Perl, Paul G Auwaerter, et al (2013) Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. The American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 70(3): 195-283.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...