Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5760

Research Article(ISSN: 2690-5760)

Knowledge, Awareness, Attitudes and Practices Regarding Cystic Echinococcosis in Khartoum State, Sudan Volume 3 - Issue 2

Sara S Abdalla1,2,4*, Mohamed E Ahmed2,3, Mazin K Mohamed4 and Martin P Grobusch2,5

- 1Department of Medical Parasitology and Entomology, Faculty of Medical laboratory Sciences, AlNeelain University, Khartoum, Sudan

- 2Medical Research Centre, Zamzam University College, Sudan

- 3Department of Surgery, Faculty of medicine, AlNeelain University, Khartoum, Sudan

- 4Alsalam Alreyad Medical centre, Khartoum, Sudan

- 5Center for Tropical Medicine and Travel Medicine Department of Infectious Diseases, Division of Internal medicine, Academic Medical Center, University of Amesterdam, The Netherland

Received:June 12, 2021 Published: June 22, 2021

Corresponding author: Sara S Abdalla, Department of Medical Parasitology and Entomology, Faculty of Medical laboratory Sciences, AlNeelain University, Khartoum, Sudan

DOI: 10.32474/JCCM.2021.03.000158

Background

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a neglected disease of public health significance worldwide, especially in low- and middle-income countries caused by the larval form (hydatid cyst) of Echinococcus species tapeworm. Control of CE is difficult and requires a community-based integrated approach. The objectives of this study were to describe, using a questionnaire survey, the characteristics, attitudes, knowledge, awareness and practices of population regarding CE and tounder stand some of the risky practices that could contribute to spread of such disease.

Introduction

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a zoonotic parasitic disease caused by larval stage of small taeniid type tapeworm known as dog tapeworm (Echinococcus granulosus) that may cause infection in herbivorous animals and humans. Echinococcosis is one of the 17 neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) stated by the World Health Organization. E. granulosus is responsible for causing CE, which affects more than 1 million people around the world and responsible for over $3 billion in expenses every year [1]. It is characterized by the development of cysts either unilocular or may be multilocular of different extents ranging from the medium sized football to the size of a pea [2]. Genus Echinococcus comprises four species, i.e., Echinococcus multilocularis, Echinococcus granulosus, Echinococcus vogeli, and Echinococcus oligarthrus. There are two more Echinococcus species E. ortleppi and E. equinus on the basis of host-parasite interaction and their probable geographical distribution [3]. Analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear genes of different Echinococcus species has led to taxonomic revisions and the genotypes G1-G3 are now grouped as E. granulosussensustricto, G4 as Echinococcus equinus, G5 as Echinococcus ortleppi, G6-G10 as Echinococcus canadensis, and the “lion strain” as Echinococcus felidis [4]. E. granulosus life cycle is maintained by its definitive cannid host, i.e., dogs that nourish the adult worm in their smaller part of their intestine while wide range of domestic livestock and human acts as an intermediate host. CE is responsible for extensive livestock and human mortality and morbidity [5]. In details life cycle of E. granulosus, adult tapeworms that are usually 3-6 mm long reside in the small intestine of definitive hosts, then hydatid cyst stages occur in herbivorous intermediate hosts, such as sheep, cattle, goats, camels, horses, pigs and humans as well. In a typical dog-sheep cycle, tapeworm eggs are passed in the feces of an infected dog and may subsequently be ingested by grazing sheep; they hatch into embryos in intestine, penetrate intestinal lining, and are then picked up and carried by blood throughout the body to major filtering organs (mainly liver and/or lungs). After localization of developing embryos in a specific organ or site, they transform and develop into larval echinococcal cysts in which numerous tiny tapeworm heads called protoscolices are produced via asexual reproduction. A single cyst can have thousands of protoscolices, and each protoscolex is capable of developing into an adult worm if ingested by the definitive host [6]. There are many social reasons favouring the life cycle of E. granulosus and prevalence of CE in various parts of the world. Many families in rural have small plots of land and live-in close proximity with their flocks and dogs.

The gathering and grazing together of groups of animals belonging to different owners lead to circulation of infections, including CE. Home slaughter and feeding of dogs with raw offals favour the parasite’s life cycle [7]. Various small and poor equipped slaughterhouses built in the area of human settlements, lack of public health education are other factors that favour the life cycle of E. granulosus. Stray dogs and other canids, especially wolves may feed on dead animals and garbage, and hunt intermediate hosts. Dogs and livestock living in close proximity with man leads to circulation of zoonotic infection. Humans are incidental intermediate hosts; they do not play a role in the transmission cycle [8]. Dogs are particularly important in zoonotic transmission due to their close relationships with humans. E. granulosus is distributed worldwide, and it occurs on all continents, including Sudan. Cystic echinococcosis is one of the most important parasitic zoonoses in all regions of Sudan, resulting in high economic losses both in the public health sector and in the livestock industry. The epidemiology of hydatidosis varies from one area to another so control measures appropriate in one area are not necessarily of value in another [9,10]. It is essential to have adequate knowledge of the disease before contemplating control programs. For achieving an operative CE control program, it is vital to assess the level of understanding about the knowledge and awareness of disease and its preventive measure and hazardous acts that spread the infection more rapidly within the community. For these reasons, an investigation is conducted to explore the CE-related knowledge and awareness among human in different localities of Khartoum state, Central Sudan.

Methods

cross-sectional survey was conducted in Khartoum state – Sudan to find out recent knowledge, attitudes and practices on the occurrence of cystic echinococcosis. The quantitative data was collected in the form of questionnaire to investigate the knowledge and awareness of CE among community members and their routine practices that were behind the factors involved in hydatid cyst infection. The descriptive survey was performed between December 2017 and April 2018 by face-to-face communication.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This is a descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted over a period from December 2017 and April 2018todetermine up on the knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and practice regarding cystic echinococcosis among human in Khartoum state, Sudan.

Study area

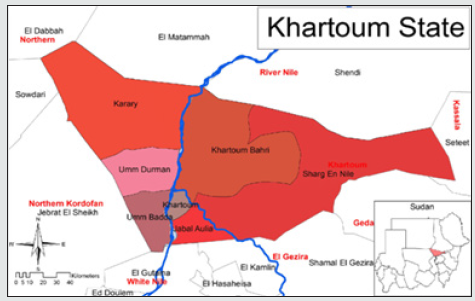

This study conducted in three townships in Khartoum state (Khartoum, Omdurman and Bahry), a part of central Sudan (Figure 1).

Khartoum State lies at the junction of the two rivers, the White and the Blue Niles in the Northeastern part of central Sudan. It lies between latitude 15-16 N and longitude 21-24 East with a length of 250 k and a total area of 20,736 km2 the surface elevation ranges between 380 to 400 m a.s.l. Most of Khartoum State falls within the semi-arid climatic zone while the Northern part of it falls within the arid climatic zone. The state is prevailed with a hot to very hot climate with rainy season during the summer and warm to cold dry winter. Rain falls ranges between 100-200 mm at the Northeastern parts to 200-300 mm at the Southern parts with 10-100 mm at the Northwestern parts. Temperature in summer ranges between 25- 40 CO during the months of April to June and between 20-35 CO during July-October Period. Temperature degrees continue to fall during the winter period between November-March to the level of 15-25 CO. Khartoum State is divided into three clusters (cities), built at the convergence of the Blue and White Niles: Omdurman to the northwest across the White Nile, North Khartoum, and Khartoum itself on the southern bank of the Blue Nile.

Data collection

Clinical data were collected by the facility medical staff via study structured questionnaire.

Questionnaires

Individuals ≥ 18 years of age were included in the study. After receiving individual verbal permission, a questionnaire was administered to obtain basic epidemiological and individual information regarding known CE risk factors. Age, sex, educational level, residence location, occupation, personal hygiene, dog ownership, dog contact, and treatment of domestic dogs were recorded. The questionnaire was administered in face-to-face interviews. Only one investigator administered the surveys, in order to prevent inter-observer differences.

Study variables

The following are the variables utilized by this study:

a) Demographic data

b) Dog ownership

c) Dog contacts

d) Treatment of owned dog

e) Home slaughtering and raw offal disposal

f) Education level

g) Knowledge of disease

Study population

five hundred and twelve individuals were enrolled in this study, 198 males and 314 females, their place of resident is in Khartoum state and their age range from ≥18 years.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was applied in order to analyze the data using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 21.0 software. Data was analyzed descriptively using the frequency table and cross tabulation.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee of Alneelain University, Khartoum, Sudan. Then study participants were first asked whether they accept to take part in the survey.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population

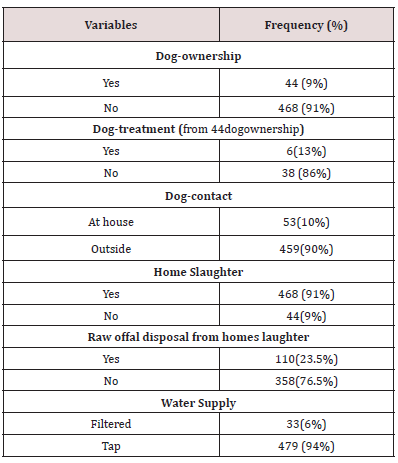

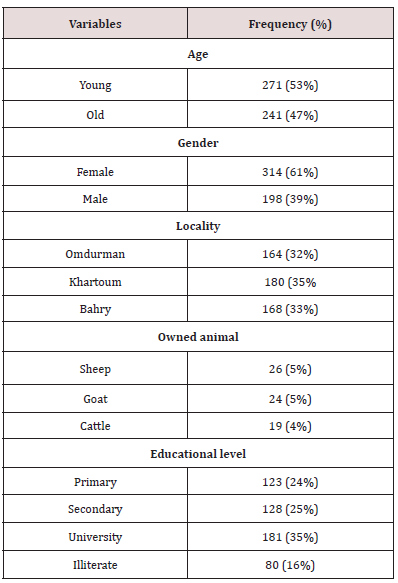

We interviewed 512 individuals, 314 (61%) female and 198 (39%) male, all of them were originated from Khartoum state. Their ages range from 18 -90 years with age mean (41.3 ± 18.08 SD) (Table 1). Regarding the populations’ level of education, 24% of the population had completed primary school, 25% for secondary school, 35% at university level, and 16% of them were unable to read and write (Table 1). Sheep and goat was the main livestock species owned by the population interviewed in this study (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of people (N = 512) participated in cystic echinococcosis (CE) knowledge, awareness and practices survey in Khartoum, Sudan.

Practices towards CE prevention

Of all the participants interviewed, 9% (44/512) indicated owning dogs on their houses (Table 2). Our result highlights some negligent dog management practices. For instance, among participants owning dogs, 13% (6/44) dewormed their dogs. Added to that, approximately all 91% (468/512) of the participants reported slaughtering livestock at home for their families’ consumption, of whom, 23.5% (110/512) they provide raw infected organ and uneatable offal like lung, intestine, etc. for their dog and cats. The interviews also revealed that the vast majority of the participants 94% (479/512) they never boiled water prior to drinking it. On the other hand,10% (53/512) of study participants come in close contact to their dogs (Table 2).

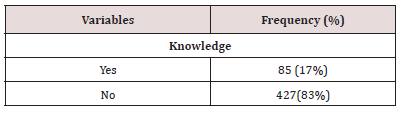

Knowledge and awareness about CE infection

The interviews revealed that 83% (427/512) of the study subjects did not know about the possibility of transmission of certain diseases (zoonoses) between livestock and humans. Small proportions 17% (85/512) of study participants had heard of hydatid disease prior, but 4.7%from them had wrong knowledge about this disease as some of them think that the hydatid cyst is a sebaceous cyst (Table 3).

Table 3: Descriptive results of study populations’ knowledge about and awareness of sources of infection with CE.

Discussion

The purpose of this descriptive study was to determine sociodemographic characteristics, awareness, household practices, and attitudes of population in Khartoum state, Sudan regarding the preventive measures against such important neglected zoonosis (cystic echinococcosis), and risky practices that could contribute to spread and persistence the disease. Parasites leading to chronic diseases can be fatal to humans and animals in warm and temperate climate countries [11]. Sudan is a country where parasitic diseases are widespread because of its geographical characteristics, wide variety of animal populations, and various other environmental and socio-cultural factors. Several potential risky practices have been underlined among the community interviewed in this study, notably practices related to dog management and treatment. Fortyfour (9%) of the surveyed person owned one or more dogs. Of these, six reported to deworm their dogs. This finding reflects a poor awareness among the population regarding the role of dogs in CE transmission. The majority of the interviewees did not de-worm their dogs, and more than half of them indicated feeding uncooked viscera to their dogs when slaughtering at home for household consumption. Such risky practices have been among the most important factors that increase contamination of the environment with faeces containing Echinococcus eggs [12]. Similar findings have been documented in other CE endemic settings. A study in Sardinia (Italy) reported that the majority of the interviewed people used raw offal, after home slaughtering, for feeding their dogs [13]. In addition, a study in Tibet demonstrated that feeding dogs with uncooked viscera is a risk factor for increasing the likelihood of human infection with E. granulosus [14].

In highly endemic areas it is quite possible for individuals to contract CE through indirect transmission through contaminated food or water [15]. Our results show that almost 94% of the respondent’s drink water directly without boiling. Water supply has been also found to be associated with infection with CE, and this may be due to water contamination with dog faeces [15,16]. Studies in Jordan [17] and Kenya [18] established that contaminated drinking water was a risk factor for human CE and detected Echinococcus eggs in water used by both people and livestock. Consequently, treatment of water prior to drinking is an important process to minimize the risk of disease transmission. Adequate hygienic handling practices and heat treatment (cooking food or boiling water) should contribute to minimizing the risk of foodborne echinococcosis. In Sudan, the incidence of Echinococcosis has probably increased in recent years as a result of increased ownership of dogs, and presence of stray dogs in close contact with people in markets and around the slaughterhouses. Also, the slaughter practices in Sudan play a vital role in maintenance of the parasite cycle because of low quality and number of slaughterhouses. In addition, slaughter at house level without any practices of safe slaughter increases chances of maintenance of the parasite. The level of knowledge of Sudan’s citizens must be increased to enable the successful control of parasites. Several studies determining high risk groups for CE and discussing the theory of “lack of knowledge can increase the disease” have been published [19-21]. We conclude that, the participants of this survey were found to be with insufficient knowledge regarding CE. Therefore, it is concluded as the disease is less aware in the community, and it is very important to impart public health education to build up public awareness about the sources of infection and its control and collaboration between veterinary and medical personnel in sharing knowledge on zoonoses and working together to identify and control zoonose.

Results

We interviewed 512 people, 314(61%) female and 198(39%) male, all of them were originated from Khartoum state (three localities: Khartoum, Omdurman and Bahry). Their ages range from 18 -90 years with age mean (41.3 ± 18.08 SD). 9% of people dog ownership in the area. Of whom only (13.6%) dewormed their owned dogs. Moreover, participants’ response also showed that 10% had contact with dogs. Approximately all (91%) of the participants reported slaughtering livestock at home for their families’ consumption, of whom, (23.5%) they provide raw infected organ and uneatable offal like lung, intestine, etc… for their dog and cats.94% reported that they never boiled water prior to drinking it. On the other hand, small proportions (17%) of study participants had heard of hydatid disease prior, but (4.7%) from them had wrong knowledge about this disease as some of them think that the hydatid cyst is a sebaceous cyst, more than half of participants knew about the hydatid disease were at university educational level. The majority of the interviewed persons were not aware about how humans get infected with CE disease.

Conclusion

The participants of this survey were found to be with insufficient knowledge regarding CE. Therefore, it is concluded as the disease is less aware in the community, and it is very important to impart public health education to build up public awareness about the sources of infection and its control and collaboration between veterinary and medical personnel in sharing knowledge on zoonoses and working together to identify and control zoonose. This study highlighted a gap in health education efforts regarding CE in Khartoum state, we advocate the implementation of training programs to improve public awareness on this important disease.

Authors’ contributions

SSA, MEA designed and coordinated the work. SSA produced the questionnaire, which was reviewed by MEA and MPG. MKM , SSA,MEA collected the data. SSA analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. MEA revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read, commented and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Agudelo Higuita NI, Brunetti E, Mc Closkey C (2016) Cystic Echinococcosis. J Clin Microbiol 54: 518-23.

- Surhio AS, Bhutto B, J Gadahi A, Akhtar N, Arijo A (2011) Studies on the prevalence of canine and bovine hydatidosis at slaughter houses of Larkana, Pakistan. Research Opinions in Animal and Veterinary Sciences 1: 40-43.

- Bowles J, Blair D, and Mc Manus DP (1995) A molecular phylogeny of the genus Echinococcus. Parasitology 110: 317-328.

- Nakao M, Mc Manus DP, Schantz PM, Craig PS, Ito A (2007) A molecular phylogeny of the genus Echinococcus inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Parasitology 134: 713–722.

- Neumayr A, Tamarozzi F, Goblirsch S, Blum J, Brunetti E (2013) Spinal Cystic Echinococcosis-A Systematic Analysis and Review of the Literature: Part 2. Treatment, Follow-up and Outcome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: 9.

- Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin F X, Pawłowski ZS (2001) (ed). WHO/ OIE manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals: a public health problem of global concern. World Organisation for Animal Health (Office; International des Epizooties) Paris, France, and World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Odero JK (2015) The burden of Cystic Echinococcosis in selected regions in Kenya. Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Science in Animal Parasitology in the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology. Kenya.

- Romig T (2003) Epidemiology of echinococcosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 388(4): 209-217.

- Bour´ee P (2001) Hydatidosis: Dynamics of transmission. World Journal of Surgery 25: 4-9.

- Siham T Karamalla, Ahmed I Gubran, Ibrahim A Adam, Tamadur M Abdalla, Reem O Sinada, et al. (2018) Sero-epidemioloical survey on African horse sickness virus among horses in Khartoum State, Central Sudan. BMC Vet Res 14(1): 230.

- Mehmet F Aydın, Emre Adıgüzel, Hakan Güzel (2018) A study to assess the awareness of risk factors of cystic echinococcosis in Turkey. Saudi Med J 39(3): 280-289.

- Possenti A, Manzano Román R, Sánchez Ovejero C, Boufana B, La Torre, G, et al (2016) Potential risk factors associated with human cystic echinococcosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10(11): e0005114.

- Varcasia A, Tanda B, Giobbe M, Solinas C, Pipia AP, et al (2011) Cystic echinococcosis in Sardinia: Farmers’ knowledge and dog infection in sheep farms. Vet Parasitol 181(2-4): 335-440.

- Li D, Gao Q, Liu J, Feng Y, Ning W, et al (2015) Knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) and risk factors analysis related to cystic echinococcosis among residents in Tibetan communities, Xiahe County, Gansu Province, China. Acta Trop 147: 17-22.

- Torgerson PR (2014) Helminth-Cestode: Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus mutilocularis. Encycl Food Saf 2: 63-69.

- Yang YR, Sun T, Li Z, Zhang J, Teng J, et al (2006) Community surveys and risk factor analysis of human alveolar and cystic echinococcosis in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, China. Bull World Health Organ 84(9): 714-721.

- Dowling PM, Abo Shehada MN, Torgerson PR (2000) Risk factors associated with human cystic echinococcosis in Jordan: results of a case-control study. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 94(1): 69-75.

- Craig PS, Macpherson CN, Watson Jones DL, Nelson GS (1988) Immunodetection of Echinococcus eggs from naturally infected dogs and from environmental contamination sites in settlements in Turkana, Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 82(2): 268-74.

- Yazar S, Akman MAA, Yay M, Hamamcı B, Yalçın Ş (2003) Investigation of Anti-Echinococ Antibodies in Shoe-Repairers İnönüÜniversitesi Tıp FakültesiDergisi 10: 21-23.

- Karaman U, Aycan MO, Atambay M, Miman O, Daldal N (2005) Analysis of anti-echinococcus antibodies in garbage men in Malatya. Turkiye Parazitol Derg 29(4): 244-246.

- Besbes M, Sellami H, Cheikhrouhou F, Makni F, Ayadi A (2003) Clandestine slaughtering in Tunisia: investigation on the knowledge and practices of butchers concerning hydatidosis. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 96(4): 320-322.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...