Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5760

Case Report(ISSN: 2690-5760)

False Brain Tumor: An Atypical Case of Intracranial Hypertension Volume 4 - Issue 3

Browne G, Deschamps J, Safaeipour M and Jaqua EE*

- School of Medicine, Loma Linda University Health, USA

Received:April 15, 2022; Published: April 21, 2022

Corresponding author: Jaqua EE, MD, DipABLM, DipABOM, FAAFP, School of Medicine, Loma Linda University Health, California, USA

DOI: 10.32474/JCCM.2022.04.000188

Abstract

Pseudotumor cerebri, also known as idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), is an uncommon disorder characterized by increased intracranial pressure with no identifiable cause. It is commonly found in obese women of childbearing age and can lead to a decreased quality of life if left untreated. Diagnosing pseudotumor cerebri can be difficult due to the varying symptoms patients can present. This case report describes an unusual presentation of pseudotumor cerebri in a typical patient.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old female with a past medical history significant for hypertension (HTN), urinary tract infection, severe obesity, and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) presents with a chief complaint of dizziness and near syncope for the past two months. The dizziness is different from the BPPV as she is unable to control her balance due to the “heaviness in her body” with subsequent falls but not an altered level of consciousness. She reported mild headaches that improved with acetaminophen but no issues with her vision.

ED visit

After the first episode, the patient was taken to the emergency department (ED) for additional evaluation. CT head and lab work was unremarkable, and she was discharged with a diagnosis of uncontrolled hypertension and recommended to follow up with a primary care doctor.

Primary Care Physician Visit

At her primary care office, HTN medications were changed, even though the patient didn’t believe her symptoms were due to HTN. Nevertheless, the patient continued to have frequent episodes associated with worsening symptoms. She went back to her primary care doctor a few weeks later after experiencing a fall at work associated with left-sided facial “heaviness,” fatigue, and lightheadedness, but no loss of consciousness. The patient also reported that every time she falls to the ground, she is unable to stand up or move by herself, losing control of her whole body.

Primary Care Physician Follow Up

The paramedics were called, but she decided not to go to the hospital and wait for her primary care doctor’s appointment. The patient expressed that she is worried that her condition is severe and is afraid that she will die. However, home systolic blood pressure levels have been in the 160-170s, which, per chart review, is consistent with the ED visit. Medications include acetaminophen, amlodipine, lisinopril, meclizine, methocarbamol, and sertraline. Physical examination was unremarkable. Repeat blood work, a 48- hour Holter monitor, stress echocardiogram, electroencephalogram (EEG), MRI Brain without contrast, and carotid ultrasound were ordered during the visit. Referrals to neurology and cardiology were also placed.

Labs and Image Results

Lab work was within normal limits, except for a mildly elevated WBC at 11.5, which improved from 15.24 at the ED. A bilateral carotid duplex demonstrated 0-15% stenosis of the bilateral internal carotid arteries. The stress echocardiogram was grossly normal and showed no signs of ischemia.

Primary Care Office Follow Up

Four weeks later, the patient returned with minimal improvement in symptoms, having not yet seen neurology or cardiology. She reported continued dizzy spells, a “heaviness sensation” in her body, lightheadedness, and a fall five days before the visit. She expressed, however, that she felt better knowing that she was being evaluated for more serious diseases. Her MRI and Holter tests were still pending.

Labs and image results + specialists’ recommendations

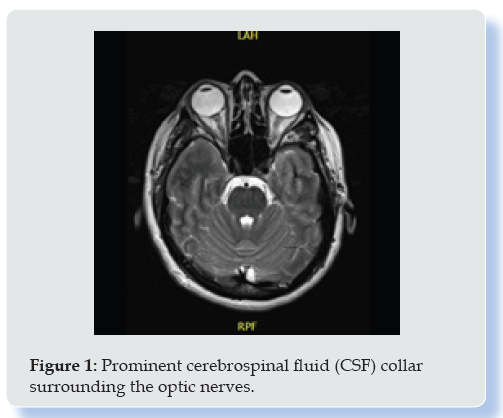

MRI of the brain showed a prominent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collar surrounding the optic nerves (Figure 1). Prominent Meckel’s caves are also noted. A 4-mm T2 hyperintensity is pointed out in the left thalamus. The brain shows otherwise normal morphology and signal characteristics. The ventricles are normal in size; however, a partial empty sella and remote tiny left thalamic infarct are noted. Findings are suggestive of intracranial hypertension. EEG was within normal limits. Cardiology suggested beginning a workup for vasovagal syncope with less suspicion for any cardiac etiology and ordered a tilt-table test. Neurology suggested that the syncopal episodes were due to her medications and started her on aspirin for stroke prevention.

Treatment

Tilt-table test returned normal. However, based on her MRI findings, she was started on acetazolamide for suspected intracranial hypertension, counseled about weight loss, and referred to ophthalmology. She reported significant improvement in symptoms at her subsequent visit and tolerated acetazolamide with minimal side effects.

Discussion

Pseudotumor cerebri is a condition that presents with chronically elevated intracranial pressure [1]. Symptoms may include diffuse headaches, transient vision loss, brief perceptions of bright flashing lights, pulsatile tinnitus, back pain, and cranial nerve (CN) disorders, especially CN VI [1]. The etiology of this condition is unknown but predominantly affects obese women aged 15 to 44 years old [2,3]. However, certain drugs like growth hormones, tetracyclines, danazol, and excessive vitamin A or its derivatives are also associated with pseudotumor cerebri [4,5]. Typically, the diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri is made using the Modified Dandy criteria, which consist of

a. The classic findings of increased intracranial pressure (headache, visual changes, pulsatile tinnitus, papilledema)

b. Absence of localized neurologic findings on the exam (except abducens nerve palsy)

c. Normal neuroimaging except for an empty sella turcica

d. Alert and awake patient

e. No other apparent cause of intracranial hypertension [6].

The ophthalmologic examination should always be performed, checking for bilateral papilledema, as well as visual field testing to reveal any blind spots or loss of peripheral vision [7,8]. MRI with contrast should also be performed to rule out other causes of increased intracranial pressure. A lumbar puncture can temporarily relieve headaches and reveal an elevated opening pressure >20 cm H2O with normal CSF analysis [7,8]. Differential diagnoses for pseudotumor cerebri include secondary intracranial hypertension and optic disc abnormalities [9,10]. Intracranial hypertension can arise secondary to intracranial mass lesions, obstructions to venous outflow, obstructive hydrocephalus, decreased cerebrospinal fluid absorption, or increased CSF production [10]. Optic disc abnormalities may also be caused by pseudo papilledema, malignant hypertension, or diabetic papillopathy. In such cases, ophthalmologic evaluation is advised to confirm the presence of papilledema [13]. General measures for the treatment of pseudotumor cerebri include discontinuation of any drugs or hormones causing increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and weight loss [8,9]. First-line medical therapy includes acetazolamide, an inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase in the choroid plexus that decreases CSF production and thus pressure.9,10 If acetazolamide is insufficient, furosemide can be added to the treatment [9]. Alternatively, indomethacin has also been shown to reduce CSF pressure in pseudotumor cerebri [10]. If these conservative treatments fail, surgical options are available, such as optic nerve sheath fenestration for visual loss and placement of a Lumb peritoneal shunt [11]. As mentioned above, the patient was prescribed acetazolamide 125 mg PO TID and reported resolved symptoms. However, she endorsed a minor burning sensation in her hands after taking the medication, which resolved after decreasing the frequency to BID.

Conclusion

As we learned in this case, the patient did not have any of the classic symptoms of pseudotumor cerebri. Instead, she presented with near episodic syncope, severe fatigue, left facial twitch, whole body “heaviness,” followed by lightheadedness without loss of consciousness. Her prodromal symptoms included a cold sensation in the head, rumbling sounds in her ear, and postural instability triggered by sudden movements or leaning forward. She denied headaches, vision changes, nausea, vomiting, or unilateral weakness. Emergent etiologies of presyncope and vertigo included, but were not limited to, stroke/TIA, vasovagal syncope, cerebral hemorrhage, cervical artery dissection, and arrhythmias but were not supported by clinical assessment and workup. All tests were negative for neurocardiogenic or vasovagal dysfunction except for the MRI brain, which showed findings suggestive of intracranial hypertension. Pseudotumor cerebri is a rare and challenging diagnosis that can be recognized if the classic signs and symptoms are present along with risk factors. However, this case illustrates a need for a high index of suspicion for severe conditions since the symptoms were not improving. Therefore, always listen, be compassionate, and don’t disregard the patient’s complaints.

References

- Jensen RH, Radojicic A, Yri H (2016) The diagnosis and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension and the associated headache. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 9(4): 317-326.

- Radhakrishnan K, Ahlskog JE, Cross SA, Kurland LT, O'Fallon WM (1993) Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Descriptive epidemiology in Rochester, Minn, 1976 to 1990. Arch Neurol 50(1): 78-80.

- Kesler A, Gadoth N (2001) Epidemiology of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in Israel. J Neuroophthalmol 21(1): 12-14.

- Donahue SP (2000) Recurrence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension after weight loss: the carrot craver. Am J Ophthalmol 130(6): 850-851.

- Friedman DI (2005) Medication-induced intracranial hypertension in dermatology. Am J Clin Dermatol 6(1): 29-37.

- Wall M (2017) Update on Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Neurol Clin 35(1): 45-57.

- Thurtell MJ, Wall M (2013) Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): recognition, treatment, and ongoing management. Curr Treat Options Neurol 15(1): 1-12.

- Julayanont P, Karukote A, Ruthirago D, Panikkath D, Panikkath R (2016) Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: ongoing clinical challenges and future prospects. J Pain Res 9(1): 87-99.

- Jensen RH, Radojicic A, Yri H (2016) The diagnosis and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension and the associated headache. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 9(4): 317-326.

- Friedman DI (1999) Pseudotumor cerebri. Neurosurg Clin N Am 10(4): 609-621.

- Förderreuther S, Straube A (2000) Indomethacin reduces CSF pressure in intracranial hypertension. Neurology 55(7): 1043-1045.

- Biousse V, Bruce BB, Newman NJ (2012) Update on the pathophysiology and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 83(5): 488-494.

- Friedman DI (2001) Papilledema and pseudotumor cerebri. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 14(1): 129-147.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...