Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5760

Research Article(ISSN: 2690-5760)

Educational Benefits of an International Service-Learning Course in Honduras for Doctor of Physical Therapy Students Volume 4 - Issue 2

Todd Watson*, Jessica Graning and Timothy Eckard

- Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC, USA

Received:December 01, 2021; Published: December 10, 2021

Corresponding author: Todd Watson, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC, USA

DOI: 10.32474/JCCM.2021.04.000181

Abstract

Background: International service-learning (ISL) activities are academic experiences that encompass participation in organized service activities, practical experiences, and critical reflection. The assessment of physical therapy clinical education is primarily achieved through student performance on the clinical performance instrument (CPI) during clinical education. The CPI assesses a student’s performance in all subdomains of professional practice and patient management and is completed during each clinical education experience.

Objective: Within the framework of an ongoing community-based program, the purpose of this study was to determine if there were differences in aggregate and subdomain performance on the CPI between Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) students enrolled in an elective ISL course and matched controls.

Methods: Twenty-three DPT students participated in an elective ISL and compared to controls matched on age, gender, cohort and clinical setting utilizing a case-control design. McNemar tests were used to compare the proportion of ISL participants and controls that had each CPI subdomain listed as a strength. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the total number of CPI subdomains listed as strengths between ISL participants and their matched controls.

Conclusion: A significantly greater proportion of ISL participants than controls had “communication” listed as a strength in the CPI comments (p=0.04). ISL participants also had significantly more subdomains listed as strengths compared to their matched controls (p < 0.01). Results suggest that participation in an ISL with an emphasis on clinical care may accelerate DPT student gains in professional communication and overall clinical performance.

Background

International service-learning (ISL) is widespread throughout higher education, with study abroad participation doubling in the years 1999-2014 [1] and no signs of lessening [2]. In the 2018-2019 academic year, 347,099 US students studied abroad, representing an increase of 2% of US students compared to the previous academic year, and an increase of 11% over the previous five years [3]. Physical therapist (PT) education strives to train skilled practitioners for a variety of health care settings, including practicing in a global health care environment [4,5]. ISL is defined [6] as a structured academic experience in another country encompassing the following three aspects in which students.

a) Participate in an organized service activity that addresses identified community needs;

b) Learn from direct interaction, gain from practical experiences and cross-cultural dialogue with others; and

c) Critically reflect on the experiences so as to advance their understanding of course content, of global and intercultural issues, gain a broader appreciation of the host country and the discipline, and an enhanced sense of their own responsibilities as citizens locally and globally.

Community engaged learning is more than simply service in a community that is for learning; but rather is collaborative, i.e., it is service-learning with the community so that all parties (students, faculty, and community members) share decisions in planning and implementation for mutual benefit [7-11]. Previous studies indicate that community engaged ISL projects provide faculty members with an opportunity to conduct clinical and translational research, [12-15] and community benefits can include extension of health care services such as support for ongoing clinics, health education campaigns, and annual health fairs [16]. Student benefits from ISL experience include fostering critical thinking skills, analysis and content mastery, [17,18] and in general a greater appreciation of the community [19]. Additionally, ISL has demonstrated positive effects on students communication skills, [20-22] and in the context of globalization, skilled intercultural communication is essential at home and abroad for effective client-centered care [23,24]. Furthermore, previous research has evidenced the enhancements of clinical reasoning (CR) skills of health professions students participating in ISL [25-27].

Purpose

While the intent of the ISL travel course had been to promote critical reflection and CR while offering an immersive global health clinical experience, the present study aimed to measure development of professional behaviors (including communication and CR) in these ISL participating students. Specifically, the purpose of this study was to determine if there were differences in aggregate and subdomain performance on the Physical Therapist Clinical Performance Instrument [28] (CPI) between Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) students enrolled in an elective ISL course and controls matched on age, gender, and cohort. The ISL took place in Honduras with an established community engaged program which occurred during a two-year time span. The value of the community engaged ISL experience had been recognized by students for several years prior to this study. In exit interviews, several students stated that participation in a ISL had greatly improved their professional development. These student reflections were reinforced by clinical instructor feedback during formative and summative assessments throughout the internships immediately following the ISL experiences. In years prior to the study, clinical instructors commented on superior levels of clinical reasoning, communication, and other professional aspects of clinical performance for the students that had participated in the ISL. It was these commentaries that were the impetus for the present study. An analysis of the present study’s participants evaluating their ISL course Reflection Papers were found to be at the highest Kember Scale level of reflection [26]. In that study, participants’ response to the ISL was limited to a consideration of reflective thinking undertaken after their return. The current study expands on this to examine how ISL participation impacts several facets of clinical performance, such as clinical reasoning and communication skills, as assessed by a student’s Clinical Instructor (CI). We hypothesized that a greater proportion of ISL participants would have the specific subdomains of communication and clinical reasoning listed as strengths in the comments section of the CPI and that ISL participants would have a greater total number of CPI subdomains listed as strengths compared to their matched controls.

Methods

Participants

Over the course of two years, 23 students across three cohorts enrolled in a cultural immersion study abroad ISL travel course led by the first author, offered as an elective through the Department of Physical Therapy a public, Carnegie classified Community Engaged, Regional Comprehensive state university in the southern United States. Participants in this study were graduate students enrolled in the DPT program which consists of a 33-month, traditional curriculum. The clinical education (CE) curriculum includes four full-time, clinical education experiences for a total of 34 weeks (two six-week experiences, one 10-week experience, and a 12-week terminal CE) with a full-time CE occurring every other semester throughout the curriculum. Participants in cohort 1 were 26 months into the curriculum and experienced the ISL course prior to their final CE. Participants in cohort 2 and 3 were 13 months into the curriculum and experienced the ISL course prior to their second CE. These three separate cohorts’ courses occurred during three recent academic years. Each of the 23 study participants that participated in the ISL were matched with a control participant who did not attend the ISL. Participants were matched on gender, age, and cohort (graduation year). Differences in CPI change scores from pre-ISL date to post-ISL date were compared within each pair in the CPI clinical performance subdomains of safety, professional behavior, accountability, communication, cultural competence, professional development and CR. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Program description

The ISL study abroad course was developed from a sustained, long-term (eight year) relationship between the primary author and local community leaders in Honduras to provide pro bono PT services in an impoverished rural region of Honduras, where no such services exist. The program was initially developed with a local Taulabé NGO Fuente de Vida in 2011 as a medical mission, and in 2013 began as a community engaged ISL course. Since then, clinics Hospital Evengélico in Siquatepeque (in 2016) and Centro Integral de Salud in Taulabé (in 2018) have joined the partnership. Leaders from each organization participated in needs assessments for the projects’ objectives, which developed into a program that not only provides annual in-country pro-bono services during the ISL, but provides health literacy education videos and pamphlets on topics chosen by the partner leaders for sustainable outcomes. These partners participated directly with study implementation, but declined to be involved in manuscript preparation due to either time commitments with their work or reported discomfort with English language writing. The community-based project is ongoing. ISL course objectives focused on students developing an understanding of

a) Typical struggles faced in the developing world (both material and non-material),

b) Global health issues typically encountered,

c) How a multifaceted, evidence-based health promotion program with community participation, can positively modify the complex socioeconomic determinants of health,

d) And the ability to communicate effectively with others from another culture.

The overarching purpose of the ISL travel course is to promote critical reflection and develop CR via the clinical experience with cross-cultural dialogue, while broadening the students’ understanding of global citizenship [10].

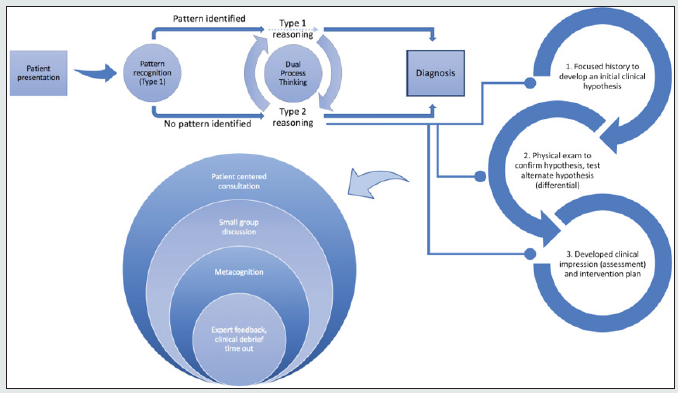

Four 2-hour intensive pre-departure training class sessions were held, in addition to required journal article topic readings on ISL and global health issues. The in-country program included a 10- day immersion in Honduras in which students provided four days of intensive, full-time supervised pro-bono outpatient PT services in Taulabé set in a school setting, and one day of supervised probono outpatient PT services in Siquatepeque in a hospital setting (Hospital Evangélico). Clinical care was given across a wide range of neuromusculoskeletal and other conditions. The in-country probono clinic utilized a punctuated vertical mentoring model, where teams of two or three DPT students utilized a 3-point teaching time-out:

a) perform a focused history to develop an initial clinical hypothesis,

b) then the physical exam, and finally

c) developed a clinical impression (assessment) and intervention plan (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Punctuated mentoring model for communicating clinical reasoning during ISL pro-bono clinic: Application of the Dual Process Thinking model of clinical reasoning in a diagnostic situation. Adapted from Croskerry, P. A universal model of diagnostic reasoning. Acad Med 2009 84(8): 1022–8 [31] and Guraya SY. The pedagogy of teaching and assessing clinical reasoning for enhancing the professional competence: a systematic review. Biotech Res Asia, 2016. 13(3): 1859-1866 [29].

This mentoring model was developed for empowering the student clinician from being collectors and reporters of information to being cultivated interpreters of knowledge [29]. Two US-licensed PTs, including one full-time faculty member in the DPT program mentored as attending PTs. Teams communicated their CR to a supervising physical therapist together at each time-out stage for mentoring, feedback and direction in accordance with the ‘Making Thinking Visible’ approach [30]. During the patient visit, wait times were used for a broad array of health education and promotion, linking patients with community resources and educating patients and family members on topics that included hypertension, obesity, nutrition and exercise. Each evening while in-country, students would gather for daily 360° cohort peer assessment feedback (assessments from others on the team) to discuss the cases and lived experiences of the day. The 360° feedback provided additional opportunity for communication of CR utilized during the day, fostering articulation of cognitive and metacognitive processes [31] These structured sessions encouraged reflective thinking processes described by Schön [32] as reflection in action and reflection on action. The daily 360-feedback practice was implemented to maximize student learning and minimize ethical and safety risks [33,34]. Students were encouraged to do daily individual journaling regarding their experiences that facilitated the writing of their assigned reflection paper.

Measurement: Physical Therapist Clinical Performance Instrument

As CR is a highly complex construct [35] it has no direct measure; therefore, we depend on indirect measures and their interpretations. As no single definition or single instrument has been agreed upon as the ‘gold standard’ for assessing CR, [36,37] and as no one strategy exists for developing CR, similarly assessing CR by DPT students also poses a challenge [38]. A recent study aimed at exploring the definition, teaching and assessment of CR identified that PT educators utilized various methods when assessing CR skills, including practical examinations, clinical affiliations or fieldwork, written exams and assignments [39]. The same study also revealed that over 92% of respondents reported using the CPI, as the primary clinical performance assessment tool (CPAT) to assess CR skills in the context of clinical practice [39]. The CPI is an 18-item assessment tool used to provide documentation of student clinical performance based on direct observation by the clinical instructor. It is organized into 6 areas of professional practice (safety, professional behavior, accountability, communication, cultural competence and professional development) and 12 areas of patient management (which includes CR). The CPI uses a VAS ordinal scale with end-point anchors to range from “novice level performance” to “entry-level performance” across the items assessed [28,40].

Analysis of longitudinal data from the CPI is uncommon. Significant score changes from midterm to final evaluations for students on successive levels of clinical placements have been shown to support the construct validity of the CPI, reflecting an incremental acquisition of clinical competencies [41,42]. A recent systematic review of multiple (14) CPATs used worldwide included the CPI in its assessment. In this review, O’Conner et al. [43] stated the CPI (version 2006) had moderate content and construct validity evidence (validity grade of B), without having identified studies examining inter-rater reliability or test-retest reliability (overall evidence grade of C). While the CPI has demonstrated fair to moderate construct validity in assessing changes in student performance from midterm to final evaluations and associations between CPI assessment and subsequent academic coursework, [41] there remain substantial concerns and challenges with the instrument. O’Conner et al [43] noted the instrument lacks interrater and test-retest reliability, and no study has yet examined metrics of reliability or validity of CPI subscale change scores, such as the minimum detectable change (MDC) or minimum important difference (MID). Without these values, it is not possible to determine if observed changes in subscale scores represent a true change in a student’s clinical performance. For these reasons, we elected to utilize the comments section of the CPI instead of subscale scores in all analyses.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all participant demographic characteristics. To test our hypotheses, data from the “strengths” comment section of the CPI provided by CI’s were analyzed. Student strengths on each subdomain listed in the comments section of the CPI were coded as “present” if there were one or more comments on a particular subdomain being a strength of a student on the CPI and “absent” if there was no mention of a particular subdomain as a strength. The proportion of participants with each subdomain listed as a strength was compared between the ISL and matched control groups utilizing a McNemar or exact McNemar test, as appropriate. In the event that the expected frequencies in the discordant cells summed to less than 10, an exact McNemar test was used. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to determine if there was a significant difference between the groups in total number of CPI subdomains listed as strengths. The study data analyst was blinded to group allocation throughout data formatting, analysis, and interpretation of results. All analyses were completed using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

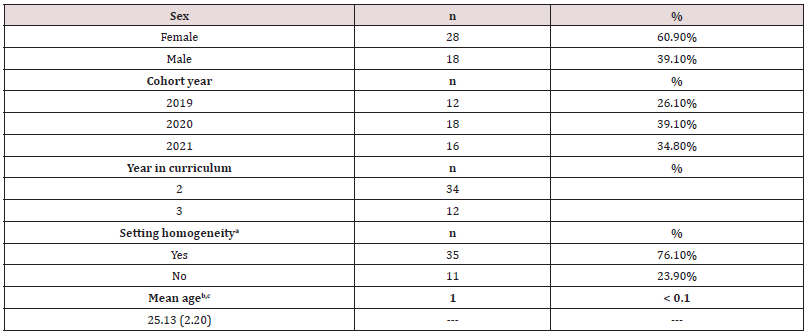

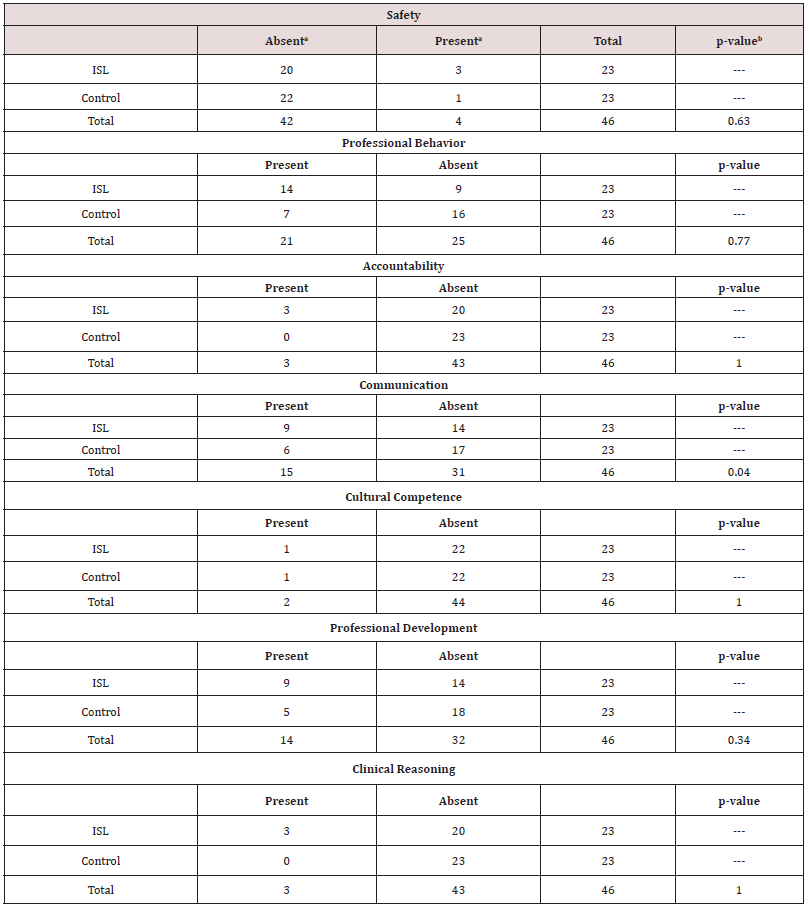

Overall, 28 females (60.9%) and 18 males (39.1%) participated in the study. The sample had similar representation among the cohorts (Cohort 1: n=12, 26.1%; Cohort 2: n=18, 39.1%; Cohort 3: n=16, 34.8%) the mean age of participants was 25.13 years with a standard deviation of 2.20 years. Complete demographic information is presented in Table 1. Each subdomain had expected discordant cell frequencies that summed to less than 10.0. Thus, exact McNemar tests were used to examine the difference in proportion of participants with each CPI subdomain listed as a strength. A significant difference was found in the proportion of participants with communication listed as a strength (p=0.04), with no other subdomains demonstrating a difference. Complete subdomain analyses are presented in Table 2. An exact Wilcoxon signed rank test comparing the number of subdomains listed as “strengths” for ISL participants compared to their matched controls yielded statistically significant results (p < 0.01). An exact Wilcoxon signed rank test was utilized because several cells had expected counts < 5.0.

a. Represents inclusion of CPI subdomain in the strengths in CPI comments section.

b. McNemar’s exact test.

Discussion

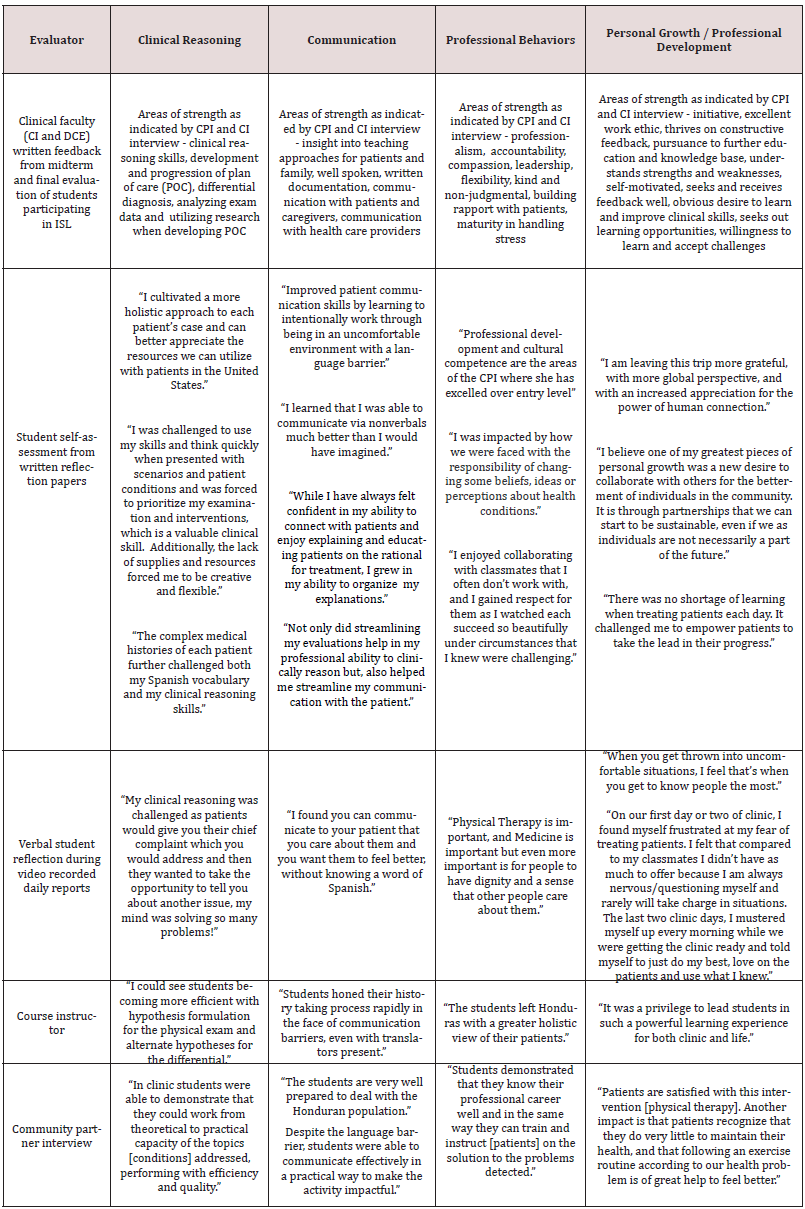

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine CPI ratings pre- and post an ISL study abroad course. This study was undertaken with the goal of determining if an intense, structured mentoring ISL improved communication and/or CR in entry-level students as measured by the CPI compared to casematched control subjects. Our results confirm our hypothesis that ISL participants would demonstrate a greater number of subdomain strengths. Additionally, ISL participants were significantly more likely to exhibit communication as a strength compared to their matched controls. Taken together, these findings indicate that an intensive ISL experience may serve as an accelerant to the development of clinical skills in DPT students. As mentioned above, results of analysis of the students’ reflection papers submitted for course credit revealed students reflection occurring at high levels, either a reflection regarding circumstances encountered through personal values or insights, or a change in perspective suggestive of a critical level of reflection that may have a bearing on their future PT practice [26]. Table 3 provides examples of the positive impact of the ISL travel course on student’s CR, communication, professional behaviors and professional development.

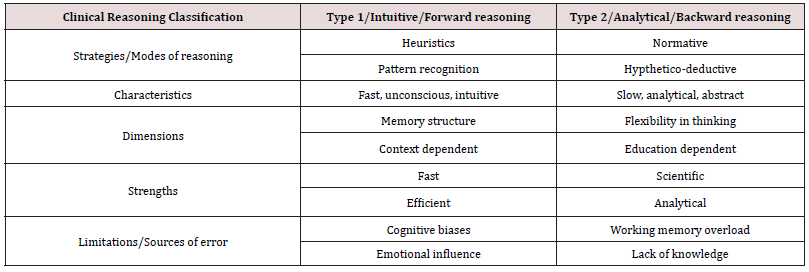

Previous research has demonstrated study abroad/international internships improve key transferable skills, specifically among them communication skills [21,44]. Communication is an important part of entry-level PT education curricula, as it is intrinsic to professional practice. Yet communication is also inherent in the CR process, irrespective of which mode of reasoning one employs (Table 4), as CR is communicated in a multifaceted way. CR is communicated first to oneself to check for reasoning errors; with colleagues to explain decision logic; and to involve and educate patients in decisionmaking. Sound communication of CR is essential to meet legal requirements of informed consent and for legal documentation of patient encounters [45]. Further, communication skills are necessary for conducting the patient interview, building empathy with patients and eliciting patients’ concerns and expectations [46,47]. Interestingly, communicating CR does not necessarily echo the actual reasoning process as reasoning is very quick and encompasses implicit knowledge [48]. Rather, communication of CR embodies a reconstruction of the processes believed as most applicable to the listener, constructed and conveyed to fit the listener [45]. Results from ‘Making Thinking Visible’ [30] methods of the reasoning reconstruction and communication have demonstrated useful for health professional students, educators and practitioners CR development.

Table 4: Clinical reasoning: A comparison of characteristics of Type 1 and Type 2 modes of ‘Dual Process Thinking’ clinical reasoning. Adapted from: Croskerry P. Clinical cognition and diagnostic error: applications of a dual process model of reasoning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009; 14:27-35 [48].

A unique feature of this ISL course was the interaction and collaboration among students and supervising PTs for communicating reasoning as well as structured reflection (360° feedback) for self, peer and mentor feedback. In addition to students explaining their own CR for cases at each time-out stage, the supervising PT guided students as they developed hypotheses and plans for case management. Development of communicative skills is well supported in literature among the major student learning outcomes commonly demonstrated from ISL courses [49,50]. An interpretation of our findings could infer that professional educational growth failed to occur for these participants across six of the seven CPI dimensions studied as a result of this intense, highly structured, reflection-oriented mentored ISL. This inference would stand in contrast with considerable research noting the high-impact practice of study abroad experiences in a diverse environment with abundant feedback from peers and professors [51,52]. Finally, there exists a strong impetus for improvement of the CPI or the development of viable alternatives, primarily driven by the need for a reliable and valid clinical assessment tool [43,53-59]. We encourage future research to calculate vital metrics of assessment tool performance, such as the minimum detectable difference and minimum important difference, for the current CPI and its subscales, as well as continued work to develop alternative assessments of student clinical performance. Although we recognize the challenges involved in assessing complex, multifaceted phenomena such as clinical performance and, like many DPT programs, continue to utilize the CPI in the absence of a clear alternative.

Funding Sources

This study is the first to examine CPI performance pre-post ISL experience. Our results support our hypothesis that participating in an ISL course experience aids the development of overall clinical performance and communication skills, but failed to show an improvement in other subdomains of clinical performance, most notably clinical reasoning.

Acknowledgments

Giovanni Alas of Fuenté de Vida Iglesia Taulabé, Honduras. Silvia Lizzeth Palada of Central Integral de Salud, Taulabé, Honduras. Dr. Hinmler Molina de Hospital Evangélica.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

Western Carolina University IRB: approval #1537513-1.

References

- Farrugia CA, Bhandari R (2014) Open Doors 2014: Report on International Educational Exchange. Institute of International Education.

- (2017 & 2021) Universities Canada. North-South mobility in Canada’s universities.

- (2021) Open Doors 2019 Executive Summary. Institute of International Education.

- Audette J (2017) “Broadening Experiences”: a method for integrating international opportunities for physical therapist students. J Phys Ther Educ 31: 49-60.

- Fell D (2013) Global Physical Therapy Academia: A Fascinating World of International Education, Research, and Service. J Phys Ther Educ 26: 3-4.

- Bringle RG, Hatcher JA, Jones SG (2011) International Service Learning: Conceptual Frameworks and Research.

- Boutin DW (2010) Service-Learning in Theory and Practice. Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Ikeda E, Sandy M, Donahue D (2010) Navigating the sea of definitions. In: Looking in Reaching out: A Reflective Guide for Community Service-Learning Professionals 2010: 17-29.

- Jacoby B (2015) Service-Learning Essentials: Questions, Answers, and Lessons Learned. 1st (ed) Jossey Bass, USA.

- Bringle R, Hatcher J (2002) Campus-community partnerships: the terms of engagement. J Soc Issues 58(3): 503-516.

- Soska TM, Sullivan Cosetti M, Pasupuleti S (2010) Service Learning: Community Engagement and Partnership for Integrating Teaching, Research, and Service. J Community Pract 18(2-3): 139-147.

- Bringle RG, Hatcher JA, Jones SG (2011) International service learning: conceptual frameworks and research.

- Calleson DC, Jordan C, Seifer SD (2005) Community-engaged scholarship: is faculty work in communities a true academic enterprise? Acad Med 80(4): 317-321.

- Zerhouni E (2003) Medicine. The NIH Roadmap. Science 302(5642): 63-72.

- Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E (2012) Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. 2nd ed, Jossey Bass, USA.

- Hunt JB, Bonham C, Jones L (2011) Understanding the Goals of Service Learning and Community-Based Medical Education: A Systematic Review. Acad Med 86(2): 246-251.

- Casile M, Hoover KF, O Neil DA (2011) Both-and, not either-or: knowledge and service-learning. Educ Train 53(2-3): 129-139.

- Sedlak CA, Doheny MO, Panthofer N, Anaya E (2003) Critical Thinking in Students’ Service-Learning Experiences. Coll Teach 51(3): 99-104.

- Simola S (2009) A service‐learning initiative within a community‐based small business. Educ Train.

- Keshwani J, Adams K (2017) Cross-disciplinary service-learning to enhance engineering identity and improve communication skills. Int J Serv Learn Eng Humanit Eng Soc Entrep 12(1): 41-61.

- Williams TR (2005) Exploring the Impact of Study Abroad on Students‘ Intercultural Communication Skills: Adaptability and Sensitivity. J Stud Intl Ed 9(4): 356-371.

- Warner B, Esposito J (2008) What’s Not in the Syllabus: Faculty Transformation, Role Modeling and Role Conflict in Immersion Service-Learning Courses. Int J Teach Learn High Educ 20(3): 510-517.

- Capell J (2007) Communicating with your clients: are you as “culturally sensitive” as you think? Physiother Can 59(3): 184-193.

- Graf J, Loda T, Zipfel S, Wosnik A, Mohr D, et al (2020) Communication skills of medical students: survey of self- and external perception in a longitudinally based trend study. BMC Med Educ 20(1): 149.

- Merritt LS, Murphy NL (2019) International Service-Learning for Nurse Practitioner Students: Enhancing Clinical Practice Skills and Cultural Competence. J Nurs Educ 58(9): 548-551.

- Watson T, Graning J, Eckard T (2020) Fostering clinical reasoning through critical reflection in Doctor of Physical Therapy Education using international service-learning in Honduras. Adv Public Health Community Trop Med 2020(2): 1-8.

- Velez R, Koo LW (2020) International service learning enhances nurse practitioner students’ practice and cultural humility. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 32(3): 187-189.

- (2020) American Physical Therapy Association. Physical Therapist Clinical Performance Instrument Web (PT CPI) 2008.

- Guraya S (2016) The pedagogy of teaching and assessing clinical reasoning for enhancing the professional competence: a systematic review. Biotech Res Asia 13(3): 1859-1866.

- Delany C, Golding C (2014) Teaching clinical reasoning by making thinking visible: an action research project with allied health clinical educators. BMC Med Educ 14: 20-25.

- Croskerry P (2009) A universal model of diagnostic reasoning. Acad Med 84(8): 1022-1028.

- Schön D (1983) The Reflective Practitioner - How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books.

- Dell EM, Varpio L, Petrosoniak A, Gajaria A, McMcarthy AE (2014) The ethics and safety of medical student global health electives. Int J Med Educ 5: 63-72.

- Rhodes G (2019) International Travel Safety in Perspective Balancing Safety Issues While Supporting Study Abroad Program Implementation.

- Osman M (2004) An evaluation of dual-process theories of reasoning. Psychon Bull Rev 11(6): 988-1010.

- Norman G (2005) Research in clinical reasoning: past history and current trends. Med Educ 39(4): 418-427.

- Young M, Thomas A, Lubarsky S, Tiffany Ballard, David Gordon, et al (2018) Drawing Boundaries: The Difficulty in Defining Clinical Reasoning. Acad Med 93(7): 990-995.

- Johnson E, Seif G, Coker Bolt P, Kraft S (2017) Measuring Clinical Reasoning and Interprofessional Attitudes. J Stud-Run Clin 3(1): 1-6.

- Christensen N, Black L, Furze J, Huhn K, Vendrely A, et al (2017) clinical reasoning: survey of teaching methods, integration, and assessment in entry-level physical therapist academic education. Phys Ther 97(2): 175-186.

- Francis NJ (2018 & 2020) Using the APTA physical therapist clinical performance instrument for students a self-guided training course.

- Roach KE, Frost JS, Francis NJ, Giles S, Nordrum JT, et al. (2012) Validation of the Revised Physical Therapist Clinical Performance Instrument (PT CPI): Version 2006. Phys Ther 92(3): 416-428.

- Adams CL, Glavin K, Hutchins K, Lee T, Zimmermann C (2008) An Evaluation of the Internal Reliability, Construct Validity, and Predictive Validity of the Physical Therapist Clinical Performance Instrument (PT CPI). J Phys Ther Educ 22(2): 42-50.

- O Connor A, McGarr O, Cantillon P, McCurtin A, Clifford A (2018) Clinical performance assessment tools in physiotherapy practice education: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 104(1): 46-53.

- Brandenburg U, Berghoff S, Taboadela O (2014) The Erasmus Impact Study: Effects of mobility on the skills and employability of students and the internationalisation of higher education institutions. Publ Off Eur Union Luxemb.

- Ajjawi R, Higgs J (2012) Core components of communication of clinical reasoning: a qualitative study with experienced Australian physiotherapists. Adv Health Sci Educ 17(1): 107-119.

- Aper L, Reniers J, Derese A, Veldhuijzen W (2014) Managing the complexity of doing it all: an exploratory study on students’ experiences when trained stepwise in conducting consultations. BMC Med Educ 2014(14): 206.

- Bowen JL, Ten Cate O (2020) Prerequisites for Learning Clinical Reasoning. In: Principles and Practice of Case-Based Clinical Reasoning Education: A Method for Preclinical Students [Internet]. Cham: Springer 2018: 47-63.

- Croskerry P (2009) Clinical cognition and diagnostic error: applications of a dual process model of reasoning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 14 (Suppl 1): 27-35.

- Miller Perrin C, Thompson D (2014) Outcomes of Global Education: External and Internal Change Associated With Study Abroad. New Dir Stud Serv. 2014(146): 77-89.

- Sakurai Y (2019) Students’ perceptions of the impacts of short-term international courses. J Res Innov Teach Learn 12(3): 250-267.

- (2016) National Survey of Student Engagement. Engagement Insights: Survey Findings on the Quality of Undergraduate Education. Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research, Bloomington, IN, USA.

- Perry L, Stoner L, Tarrant M (2012) More Than a Vacation: Short-Term Study Abroad as a Critically Reflective, Transformative Learning Experience. Creat Educ 3(5): 679-683.

- Anderson C, Cosgrove M, Lees D, Gigi Chan, Barbara E Gibson, et al (2014) What clinical instructors want: perspectives on a new assessment tool for students in the clinical environment. Physiother Can 66(3): 322-328.

- Sharp A, North S (2020) Student Performance Assessment in the Clinical Learning Environment: Taking the Leap From CPI to CIET. In: Combined Sections Meeting Abstracts. American Physical Therapy Association, USA.

- O Connor A, Cantillon P, McGarr O, McCurtin A (2018) Navigating the system: Physiotherapy student perceptions of performance-based assessment. Med Teach 40(9): 928-933.

- Torres Narváez M R, Vargas Pinilla O C, Rodríguez Grande E I (2018) Validity and reproducibility of a tool for assessing clinical competencies in physical therapy students. BMC Med Educ 18(1): 280.

- Kanada Y, Sakurai H, Sugiura Y, Hirano Y, Koyama S, et al (2016) Development of clinical competence assessment tool for novice physical and occupational therapists-a mixed Delphi study. J Phys Ther Sci 28(3): 971-975.

- Murphy S, Dalton M, Dawes D (2014) Assessing Physical Therapy Students’ Performance during Clinical Practice. Physiother Can Physiother Can 66(2): 169-176.

- Dalton M, Davidson M, Keating J (2011) The Assessment of Physiotherapy Practice (APP) is a valid measure of professional competence of physiotherapy students: a cross-sectional study with Rasch analysis. Journal of Physiotherapy 57(4): 239-246.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...